US-Uganda Migration Agreement: A Deep Dive into the Asylum Outsourcing Deal

A recently published migration agreement between the United States and the Republic of Uganda has ignited intense debate and scrutiny. Officially titled the “Agreement Between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of the Republic of Uganda for Cooperation in the Examination of Protection Requests,” the deal, signed in Kampala by US Ambassador William Popp and laid out in the US Federal Register, establishes a framework for transferring asylum seekers denied protection in the US to the East African nation. While the US gains a mechanism to outsource its international responsibilities, the pact raises profound questions about Uganda’s capacity, its true motivations, and the very nature of state power. This analysis comprehensively examines the deal’s text, from Uganda’s “complete discretion” to the legal safeguards critics fear are merely cosmetic. We explore the stark contrast between Uganda’s role as a major refugee host and its historic abandonment of indigenous communities like the Twa people. Furthermore, we situate the agreement within wider geopolitics, including Kampala’s efforts to repair trade relations after its suspension from the AGOA pact. This is more than a policy shift; it is a stark lesson in how states operate, prioritising diplomatic transactions over human dignity and exploiting division to maintain control. Join us as we unpack the implications of this controversial deal for refugees, for Uganda’s overstretched communities, and for the future of international protection itself.

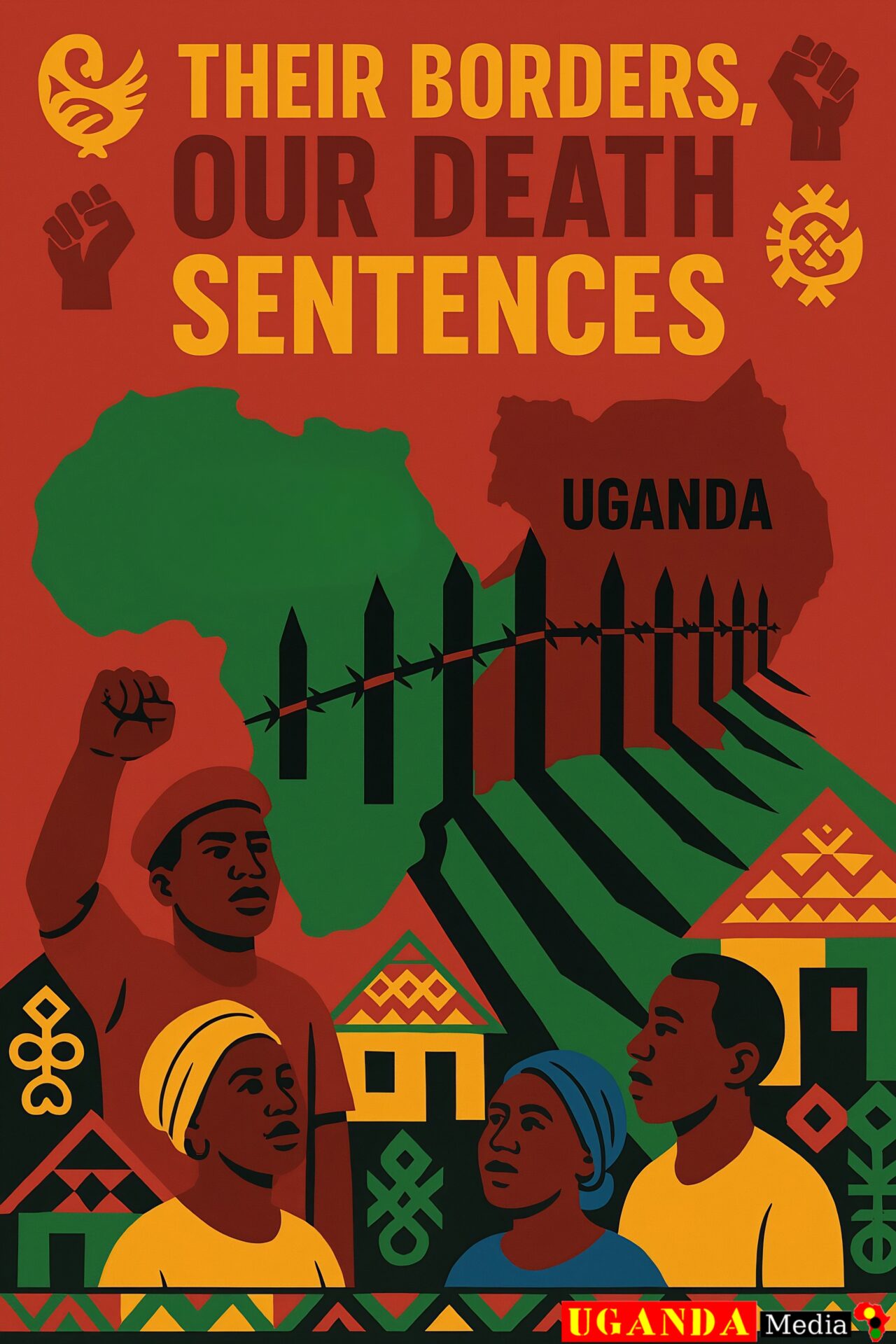

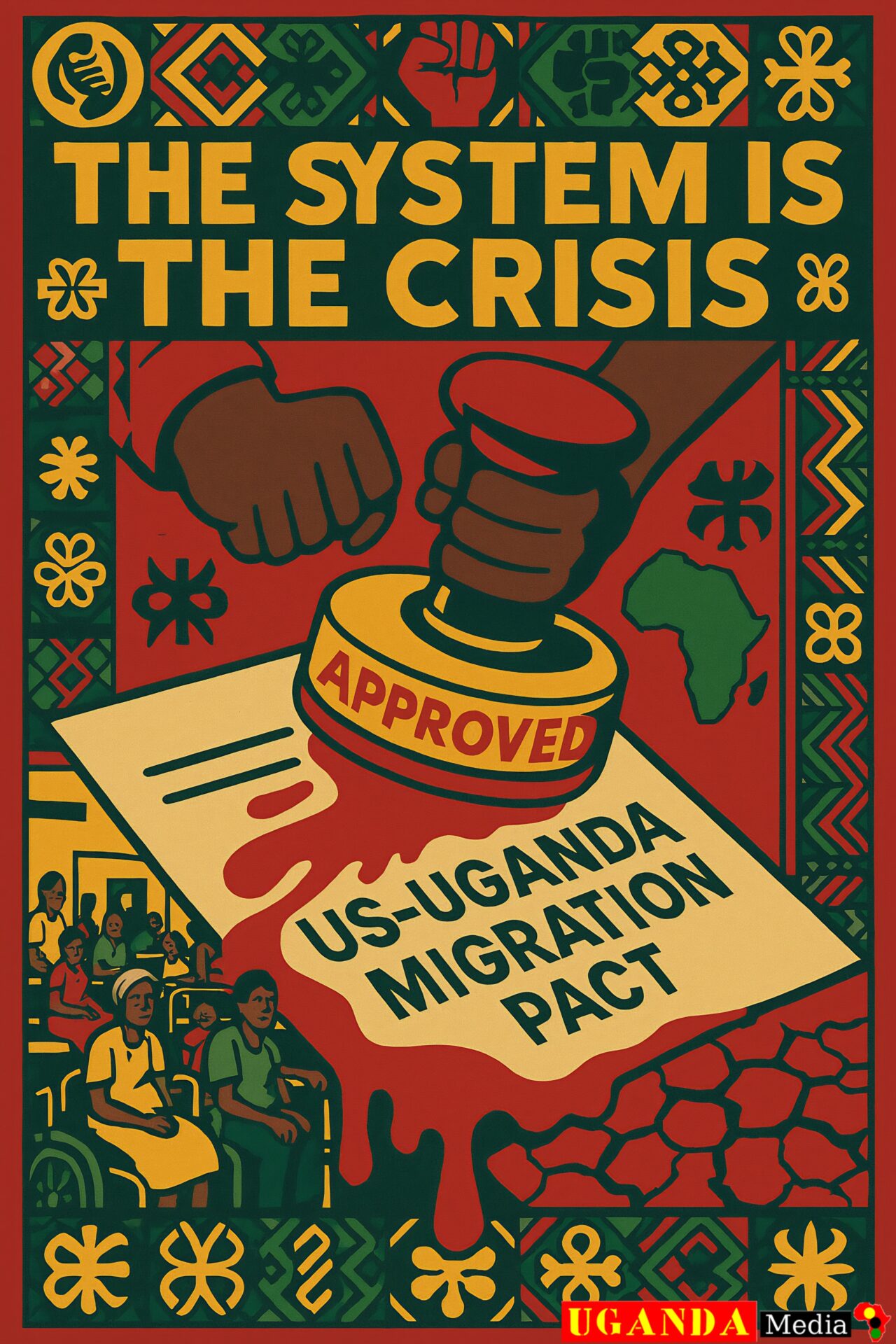

A New Colonial Pact: How Global Powers and Local Elites Trade Human Lives

In the shadow of lush hills and amidst the resilience of over 1.5 million displaced souls, a new deal is struck. The ink dried on July 29th in Kampala, on an agreement that sees human beings not as rights-bearing individuals, but as political commodities to be traded between states. The United States and the regime of President Yoweri Museveni have signed a migration cooperation deal, laying bare a brutal calculus of power where the world’s most vulnerable pay the price. This isn’t about protection; it’s a modern-day rendition of an old, cruel game where borders are drawn by the powerful, and the rest of us are expected to fall in line.

This article will dissect this arrangement, not through the sanitised language of diplomats, but through the lived reality of those it will inevitably crush. We will explore how such pacts reinforce oppressive systems, betray local communities, and reveal the true nature of state power.

Twenty Key Points on the US-Uganda Migration Pact

The Illusion of Volition: A Deeper Look

The carefully crafted notion that the Ugandan state possesses “complete discretion” in this migration agreement is a masterclass in political theatre. It is designed to be seen, applauded, and misconstrued by an audience both at home and abroad. This so-called sovereignty is not a shield for the people; it is a smokescreen for the regime, a deliberate illusion to mask the raw mechanics of power and accountability.

From a radical perspective, that questions all top-down power, this “discretion” is the Agreement’s most poisonous clause. It does not empower Uganda; it ensnares it. The regime in Kampala, ever eager to perform its role as a decisive and independent actor on the world stage, gets to grandstand about its national sovereignty. It can thump its chest and proclaim to its citizens that it alone holds the key, that it will only accept those it deems fit. This is a powerful narrative for domestic consumption, feeding the myth of a strong, paternalistic state protecting its interests.

However, this carefully stage-managed control is a double-edged sword that ultimately cuts the people, not the rulers. By making Uganda the final arbiter, the agreement brilliantly outsources the entire burden of failure. When—not if—this policy leads to crisis, the script is already written. Should overcrowded refugee settlements become hotspots for disease and conflict, should tensions with local communities boil over into violence, or should funds meant for support vanish into the pockets of officials, the blame will fall squarely on the Ugandan administration’s “discretionary” decisions.

Washington, having handed off the human cargo, can simply wash its hands of the matter. They will point to the agreement and note, with feigned regret, that the selection and integration were entirely Kampala’s responsibilities. The ultimate result is that a regime already accused of neglecting its own indigenous people, like the Twa, and of prioritising certain foreign interests, will now be left to manage the inevitable fallout from a problem it did not create, using a discretion that is more curse than power.

There is an old adage that speaks to this dynamic: “When two elephants fight, it is the grass that suffers.” In this case, the elephants are not fighting; they are shaking hands. The US extends its reach through outsourcing, and the Ugandan regime extends its control through a performance of authority. But the outcome remains the same: it is the grass—the ordinary Ugandan in the village, the existing refugee hoping for a scrap of dignity, and the asylum seeker being shipped to an uncertain future—that will be trampled underfoot.

This illusion of volition is therefore the cornerstone of the entire cynical pact. It allows powerful states to maintain a veneer of order while offloading their consequences on weaker partners. It allows local elites to bolster their image of strength while setting the stage for future crises they can then use to justify even greater control and demand more resources. It is not a tool of protection; it is a tool of predation, disguised as a choice. True freedom and autonomy lie not in a state’s right to choose who it rejects, but in communities having the power to decide how they live together, free from the manipulative deals struck in faraway capitals.

A Transaction, Not a Treaty: The Currency of Human Flesh

To view the migration pact between the US and Uganda as a humanitarian instrument is to fundamentally misread the nature of power. It is not a treaty built on principles of solidarity or protection; it is a crude diplomatic transaction, a barter deal conducted over a negotiating table where the commodity is human life. This arrangement reveals the cold, calculative logic of the state, where every action, even those draped in the language of charity, serves a strategic political or economic end.

Kampala’s motivation is laid bare by recent history. The suspension from the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) was a significant blow, not to the political elites in their guarded compounds, but to the countless Ugandan workers, farmers, and factory hands whose livelihoods were tied to tariff-free access to the American market. This loss exposed the regime’s vulnerability and its desperate need to regain favour and leverage with Washington. In this context, the migration deal emerges not as an act of benevolence but as a calculated offering—a quid pro quo where the regime hopes to trade a service for reinstatement into the economic fold.

From a perspective that seeks to dismantle hierarchies of power, this is the ultimate corruption of human dignity. People fleeing persecution, violence, and despair are reduced to abstract units in a geopolitical equation. They become a currency, a bargaining chip to be exchanged for trade privileges and diplomatic goodwill. The state, which routinely fails to provide for its own citizens—witness the continued marginalisation of indigenous communities and the chronic underfunding of public services—now seeks to profit from the desperation of others. It is a grift of monumental scale, where the regime acts as a broker for human misery, hoping to swap it for political capital.

There is a piercing adage that fits this macabre dance: “The goat offered in friendship is never lean.” The Ugandan regime, in offering this service to its American counterparts, is presenting a fattened goat. It is offering up the nation’s capacity, its land, and the resilience of its people as the meat in this transaction. But the friendship is an illusion, and the ones who will be left to chew on the bones of this deal are the common citizens and the asylum seekers themselves. The benefits will be siphoned upwards, to the very architects of the agreement, while the burdens—the strained resources, the social tensions, the human cost—will be heaved onto the shoulders of those already struggling to survive.

This transaction strips away any pretence that states exist to serve their people. Instead, it demonstrates that people, both native and foreign, are mere instruments for the state’s perpetuation and enrichment. It is a stark reminder that true change will never come from appealing to the morality of such power structures, for they operate on a calculus of profit and loss, not of right and wrong. Our solidarity must therefore be horizontal, among ourselves, and utterly opposed to these vertical deals that treat human beings as a currency to be spent.

The Myth of “Capacity”: A Dangerous Deception

The notion that Uganda possesses the spare “capacity” to humanely absorb asylum seekers from the other side of the globe is not merely an oversight; it is a dangerous and deliberate fiction. It is a myth propagated by those in power to justify a transaction that serves their interests, while the devastating consequences will be borne by the most vulnerable in our societies. To understand this myth is to see the utter contempt with which the state views the people it claims to serve.

The reality on the ground is one of profound strain. Uganda already hosts over one and a half million refugees, a testament not to the state’s competence, but to the resilience and often-forced generosity of border communities. Settlements in places like Nakivale and Kyangwali are stretched to their breaking point. Resources like water, firewood, and arable land are sources of constant tension. Clinics are overwhelmed, schools are overcrowded, and the promise of support is often a hollow one. To speak of “capacity” in this context is an insult to those living these realities every day.

This myth is weaponised by the state for a cruel purpose. It creates a façade of order and benevolence, behind which the regime can pursue its diplomatic bargains with Washington. By promoting this false narrative, the state masks the truth: that this deal will inevitably deepen the suffering of both the existing refugee population and the new arrivals, not to mention the Ugandan citizens living alongside them who are competing for the same scarce resources. It is a strategy of adding weight to a branch that is already cracking, all while claiming the tree is strong enough to hold.

This myth is weaponised by the state for a cruel purpose. It creates a façade of order and benevolence, behind which the regime can pursue its diplomatic bargains with Washington. By promoting this false narrative, the state masks the truth: that this deal will inevitably deepen the suffering of both the existing refugee population and the new arrivals, not to mention the Ugandan citizens living alongside them who are competing for the same scarce resources. It is a strategy of adding weight to a branch that is already cracking, all while claiming the tree is strong enough to hold.The hypocrisy is staggering. Consider the state’s historic neglect of its own indigenous people, such as the Twa, who have been systematically dispossessed of their lands and left without support, their culture, and livelihoods eroded by the very forces of “development” and state control. How can a state that abandons its first people suddenly find boundless capacity to care for foreigners with no regional ties? The answer is that it cannot and it will not. This deal is not about care; it is about leverage. The well-being of people is the last thing on the minds of the architects of this pact.

An old adage warns us: “Do not try to borrow a blanket from a man who is sleeping naked.” The Ugandan state, in its desperation to curry favour with global powers, is pretending to own a blanket it does not have. It is offering a comfort and security it cannot provide. The inevitable result will be that everyone is left colder. The existing refugees will see their already meagre share diminished. The new arrivals will be placed into a system that cannot support them, leading to resentment and conflict. And the host communities will be pushed further into poverty.

From a perspective that values genuine mutual aid over state coercion, the solution is not to believe the myth but to reject it utterly. True capacity is not decreed from government offices; it is built from the ground up through voluntary cooperation, shared resources, and direct solidarity between communities. This top-down imposition, driven by the interests of power, can only lead to ruin. It is our responsibility to see this myth for what it is—a lie that will get people hurt—and to build real networks of support that operate despite the state, not because of it.

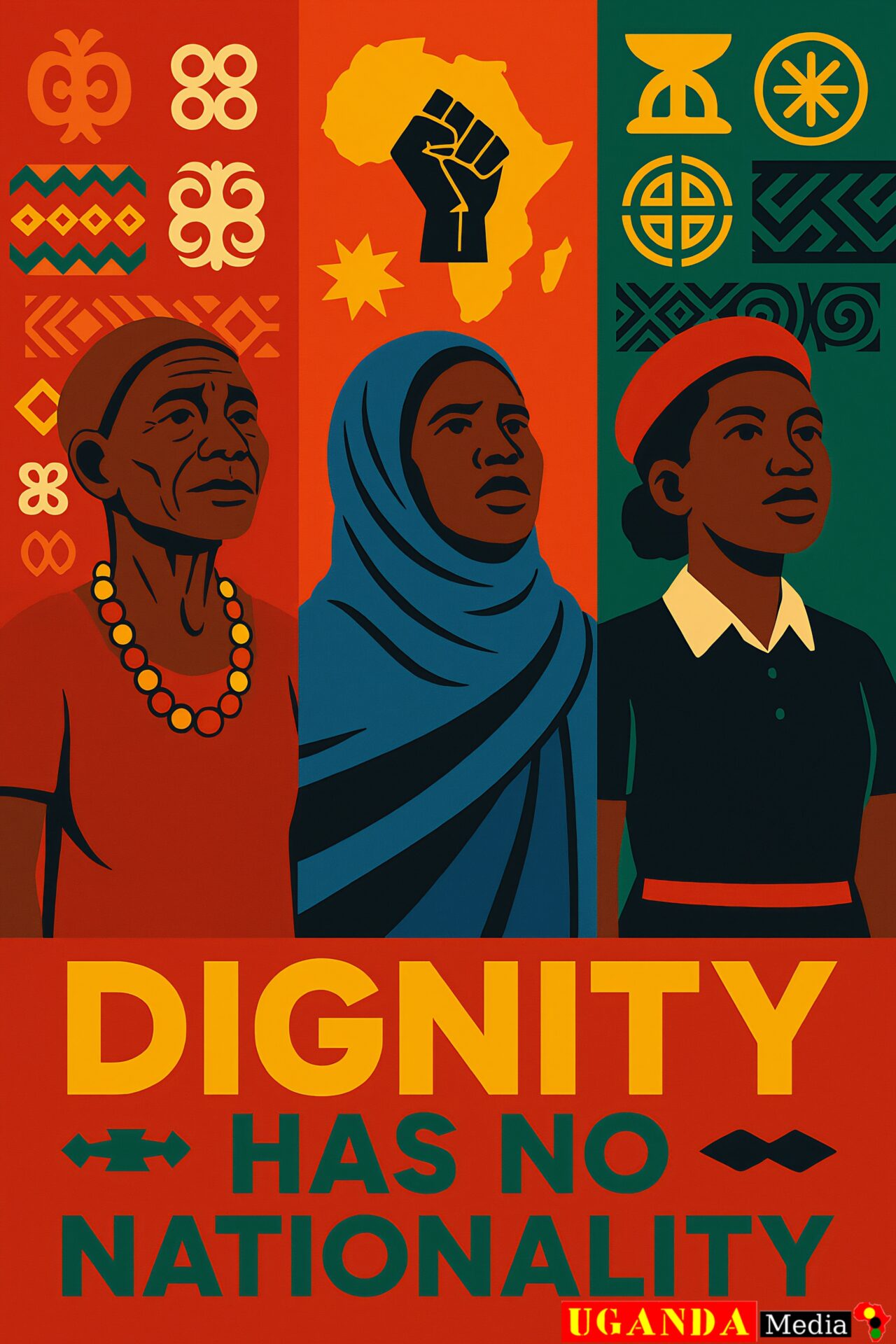

The Abandonment of the Indigenous: A Legacy of Betrayal

The Ugandan state’s fanfare around its so-called “hospitality” towards refugees is a performance of breathtaking hypocrisy. It is a carefully staged theatre intended for an international audience, designed to secure funding and political favour. This performance collapses under the slightest scrutiny when contrasted with the state’s historic and ongoing abandonment of its own first people, the Twa. Their silent, systematic erasure exposes the brutal truth about whom the state truly serves, and it is not the marginalised, the vulnerable, or the indigenous.

For generations, the Twa people have been custodians of the land, their lives, and culture intricately woven into the forests of western Uganda. The modern Ugandan state, however, operates on a logic of control, extraction, and forced assimilation. Through the creation of protected national parks and the allocation of land to commercial interests, the state has systematically dispossessed the Twa of their ancestral territories. This was not an unfortunate accident of progress; it was a calculated act of displacement. Uprooted and relegated to the margins of a society that views them with prejudice, the Twa now face extreme poverty, malnutrition, and a profound loss of cultural identity. They are denied basic services, meaningful representation, and any right to determine their own future.

This neglect is a testament to the state’s core function. It does not exist to uplift all people; it exists to maintain a hierarchy of value. It serves the interests of a privileged few—the political class, the military elite, and connected foreign investors—while discarding those who offer no political utility or who stand in the way of its projects of control. The Twa, with no powerful lobby and no leverage in the corridors of power, are deemed expendable. Their plight is a silent scream against the myth of a government that works for its citizens.

Therefore, to see this same state posture as a generous host to refugees is to witness a profound moral corruption. The “hospitality” is not rooted in a genuine ethic of care or solidarity; it is a strategic commodity, a performance piece. It is offered to those who can be used as pawns in a larger geopolitical game to win favour with Washington, while it is brutally denied to those whose roots in the soil are the deepest. The state’s embrace of the foreigner in this instance is not kindness; it is a transaction that highlights its cruel indifference to its own.

There is an adage that cuts to the heart of this: “A man who cannot build his own family’s home has no business promising to roof the entire village.” The Ugandan state has left its own children—the Twa—to sleep in the rain, exposed and forgotten. Yet, from a position of utter dereliction, it now boasts to the world that it will provide shelter for all. This is not capacity; it is a cynical deception. The roof it promises is made of paper, and the first storm will tear it away, leaving everyone—new arrivals and long-suffering hosts alike—drenched and betrayed.

This stark contrast reveals that the state’s allegiance is not to people, but to power. Its actions are not guided by principle, but by opportunism. Any genuine belief in community and mutual aid must therefore begin by recognising this betrayal and seeking to build solidarity from the ground up, bypassing the state’s hollow theatrics and addressing the needs it so wilfully ignores. True sanctuary is not granted by states; it is built by people, for people, on a foundation of shared dignity, not political expediency.

A Government That Favours the Foreign Elite: The Hierarchy of Power

To examine the migration pact in isolation is to miss the broader, more insidious pattern it represents. This deal is not an anomaly; it is a single thread in a much larger tapestry woven by a regime that has long privileged certain non-indigenous groups for its own political and military survival. This has fostered a deeply entrenched hierarchy of citizenship, where loyalty to the power structure is valued above all else, and where ordinary Ugandans are consistently sidelined in favour of a transnational elite.

The heart of this matter lies in questions of allegiance and origin. The persistent questions surrounding the President’s own place of birth in Rwanda are not merely gossip; they fuel a pervasive belief that the core loyalty of the ruling clique lies not with the soil of Uganda or the welfare of its multitude of citizens, but with a narrower, transnational network of power. This perception, whether literally true or not, is a powerful political symbol. It signifies a leadership that may see itself as answerable to a different set of interests, one that transcends national borders and the common good.

This worldview manifests in tangible, destructive ways. For decades, the state’s security apparatus has been heavily influenced by officials and commanders drawn from a specific western regional background, often at the expense of a more national representative structure. This creates a praetorian guard, loyal to the individual leader rather than the constitution or the citizenry. Furthermore, the regime’s economic policies have frequently favoured foreign investors and a small, connected local clique, granting them vast tracts of land and lucrative contracts, while Ugandan farmers and small business owners are displaced and disregarded. This is a system designed to consolidate power, not to nurture a nation.

In this context, the asylum deal is merely an extension of this logic. It demonstrates that for the regime, people—whether citizens or foreigners—are valued only for their utility to the power structure. Certain foreigners are welcomed as military enforcers or economic partners, while others may now be accepted as diplomatic currency to be traded for Washington’s favour. Meanwhile, indigenous communities like the Twa, who offer no such strategic utility, are left to rot in neglectful obscurity. Even the common Ugandan citizen is disenfranchised, watching as their nation’s resources and their government’s attention are directed towards serving the interests of outsiders and the elite.

This creates a brutal adage to live by: “The tree that shelters you is not determined by its fruit, but by whose hand controls the axe.” For ordinary Ugandans, the state is not a sheltering tree. It is an instrument of exclusion, controlled by a hand that wields the axe of discrimination, clearing away those who do not serve its immediate purpose. The Twa are cut away for their powerlessness; the poor are cut away for their lack of influence; and now, asylum seekers are being brought in not for their humanity, but because they can be used as political timber to build a bridge back to international legitimacy.

This is the ultimate betrayal of a population. It reveals a government that operates as a commercial enterprise or a private militia, not as a body for the public good. It proves that the entire structure is designed to serve itself and its allies, not the people it claims to represent. Therefore, any hope for justice cannot be found in appealing to this structure. It must be found in building power from below—in communities organising their own defence, their own economies, and their own forms of solidarity that recognise no hierarchy of citizenship, only a common humanity and a shared right to the land and its bounty.

This is the ultimate betrayal of a population. It reveals a government that operates as a commercial enterprise or a private militia, not as a body for the public good. It proves that the entire structure is designed to serve itself and its allies, not the people it claims to represent. Therefore, any hope for justice cannot be found in appealing to this structure. It must be found in building power from below—in communities organising their own defence, their own economies, and their own forms of solidarity that recognise no hierarchy of citizenship, only a common humanity and a shared right to the land and its bounty.The Weaponisation of Bureaucracy: The Gavel and the Blade

The migration agreement’s promises, particularly those in Articles 2 and 3 that pledge compliance with international refugee conventions and humane treatment, represent a profound and deliberate deception. They are not commitments to justice; they are tools of legitimisation. These clauses will be administered by the very state machinery that has perfected the art of using bureaucracy not as a shield for the vulnerable, but as a weapon against them. This exposes a central truth of power: a law written on paper is meaningless when the hand that enforces it is arbitrary and violent.

In Uganda, the institutions of the state—the police, the judiciary, the immigration authorities—are not neutral arbiters of law. They are widely understood to be instruments of control, patronage, and coercion. For the ordinary citizen, encounters with officialdom are often defined by the threat of extortion, the caprice of officials, or the blunt force of the state’s security apparatus. The same system that allows a connected individual to seize land with impunity is now tasked with upholding the sacred principle of non-refoulement for foreign asylum seekers. This is a grotesque paradox.

The agreement’s reference to international law is therefore a smokescreen. It provides a veneer of respectability for Washington and a performance of compliance for Kampala. It allows both powers to point to a document and claim the high ground of legality. However, on the ground, the reality will be starkly different. The “national procedure” established to determine the status of transferred individuals will not exist in a vacuum. It will be subject to the same corrupting influences that pervade every other state function.

An asylum seeker’s fate may hinge not on the merit of their case, but on the whims of an official having a bad day, the availability of a bribe, or the shifting political winds from above. The promise not to return a person to danger could be voided by a deliberately delayed file, a “lost” application, or the creation of such intolerable conditions in a settlement that the individual feels compelled to leave. This is how bureaucracy kills without lifting a sword; it kills through neglect, obstruction, and the silent, paper-shuffling violence of indifference.

This dynamic brings to mind a piercing adage: “It is the same knife that cuts the goat that sharpens the pencil for the butcher’s accounts.” The state’s machinery is that knife. Its blunt edge is the violent eviction of the Twa from their forests, the brutal dispersal of a protest, or the extrajudicial arrest of a critic. Its sharp, precise edge is the bureaucracy that legalises that violence post-hoc—the court order that justifies the land grab, the official form that records the detainee, and now, the asylum procedure that will legitimise a potentially cruel and negligent system.

For the transferred asylum seeker, this means their safety is entrusted to the very structure that has proven itself hostile to the weak. For the Ugandan citizen, it is a reminder that the state’s capacity for meticulous administration is never directed towards providing clean water or quality education for them, but is readily deployed to service the geopolitical interests of the powerful.

For the transferred asylum seeker, this means their safety is entrusted to the very structure that has proven itself hostile to the weak. For the Ugandan citizen, it is a reminder that the state’s capacity for meticulous administration is never directed towards providing clean water or quality education for them, but is readily deployed to service the geopolitical interests of the powerful.Ultimately, this weaponisation of bureaucracy reveals that the law itself is a malleable tool for those in power. It can be written, rewritten, or ignored to suit their needs. This demonstrates that true justice and protection can never be reliably outsourced to a coercive state apparatus. They must be cultivated through the direct action of communities building their own systems of accountability and mutual aid, systems that operate with transparency and whose only allegiance is to human dignity, not to the cynical dictates of a signed agreement.

Deepening Social Strains: Engineering Crisis to Cement Control

The decision to transfer asylum seekers to a nation already buckling under the weight of extreme poverty, mass unemployment, and crippling resource scarcity is not merely short-sighted; it is a calculated act of social engineering. This policy is a recipe for conflict, and the state, in its cynical calculus, understands this perfectly. By pouring new arrivals into this volatile mix, the regime is not solving a crisis—it is creating one. This manufactured tension then allows the state to position itself as the indispensable mediator, the strong hand needed to manage the very chaos it engineered, thereby justifying its own expansion and brutality.

Across Uganda, communities are in a daily struggle for survival. Competition for land, water, jobs, and even firewood is already fierce. In the arid Karamoja, in the fishing villages on the lakes, and in the overcrowded urban centres, life is a precarious balance. To introduce a new group of people into this fray, with their own needs and claims to scarce resources, is to throw a lit match onto kindling. The state, which has spectacularly failed to create an economy that serves the many, is now actively importing a new pressure point.

This is not a passive failure; it is an active strategy. When conflict inevitably erupts—between newcomers and long-term residents, between different ethnic groups, or between everyone and a state that provides nothing—the government will be ready. It will step in, not to address the root causes of the strife (poverty and state neglect), but to manage its symptoms with force. Soldiers will be deployed to “keep peace,” curfews will be imposed, and dissent will be framed not as a righteous anger against injustice, but as dangerous tribalism or xenophobia that must be quashed for “national unity.”

This manoeuvre is as old as power itself. It follows a piercing adage: “A cunning fisherman muddies the water to make the fish easier to catch.” The state is that fisherman. By muddying the social waters—by deepening competition and ensuring resources are ever scarcer—it makes the population easier to control. Our attention is diverted from the powerful who steal the entire lake and is turned instead towards our neighbour, who is trying to catch the same single fish we need to feed our family. We are set against each other, fighting for crumbs, while the real architects of our misery watch from a safe distance, preparing to restore “order” on their own terms.

We have seen this before. The historic marginalisation of the Twa people was a act of social strain, creating a permanent underclass to be exploited and ignored. The current neglect of struggling communities is a form of control through deprivation. This migration pact is simply the latest and most brazen iteration of this tactic.

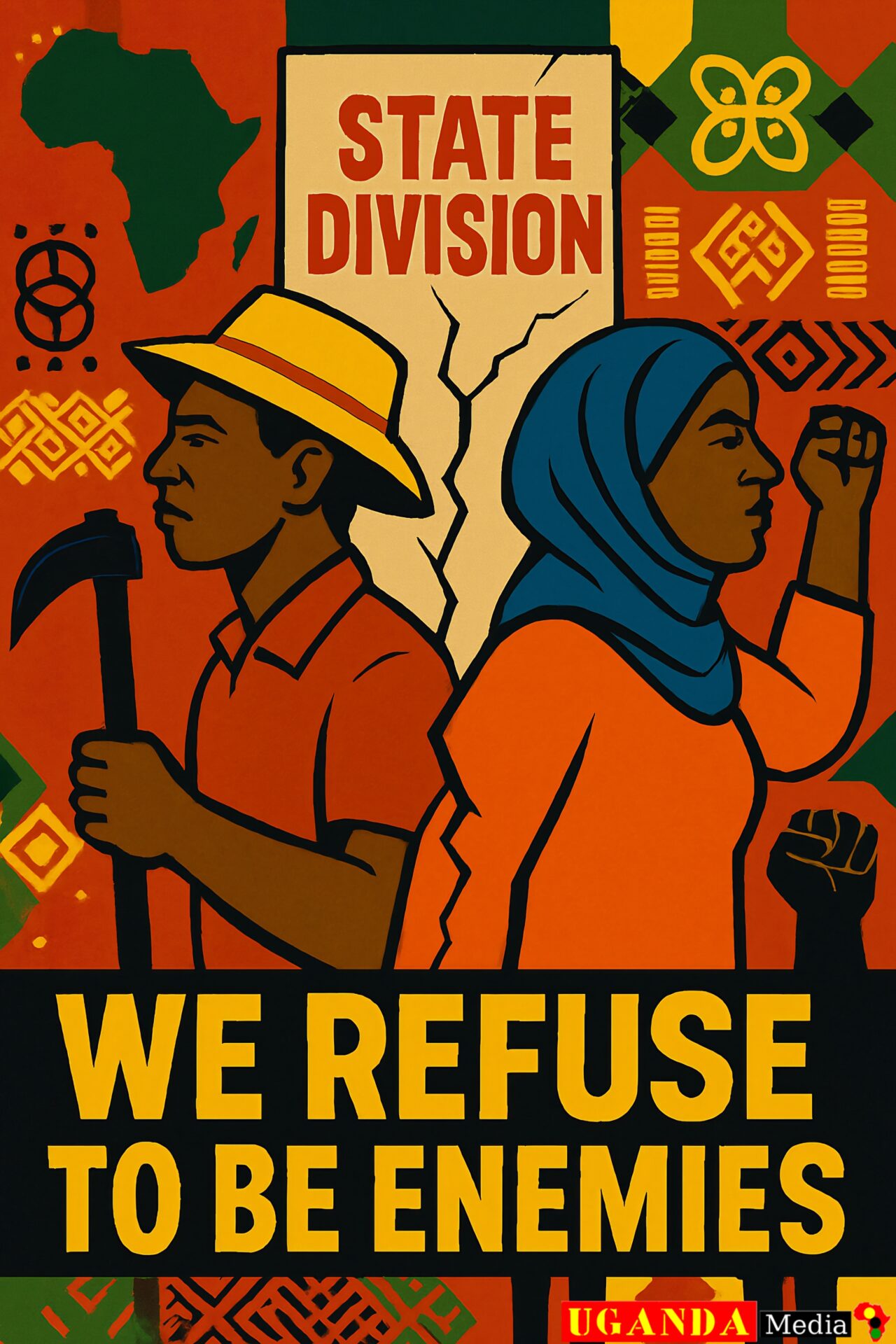

Therefore, the only rational response is to see this strategy for what it is and to refuse to play our assigned part. True solidarity means recognising that the struggle of the landless Ugandan farmer is the same as the struggle of the displaced asylum seeker. Both are victims of a global system of power that values borders and profits over people. Our fight is not against each other, but against the state that purposefully pits us against one another to hide its own failures and crimes. Our resistance must be to build networks of mutual aid that bypass the state entirely, sharing resources directly and standing together against the cynical forces that seek to divide and conquer us all.

The “Good Refugee” vs. “Bad Refugee” Narrative: Manufacturing Worth

The Ugandan Permanent Secretary’s stated preference for accepting African nationals under the new migration pact is not a minor detail; it is the revelation of a brutal state logic. It creates a deliberate and divisive hierarchy of human worth, signalling that to the regime, some lives are more palatable, more manageable, and ultimately more valuable as political currency than others. This is not hospitality; it is a cold-blooded sorting mechanism based purely on the accident of origin, a practice that should disgust any person who believes in inherent human dignity.

This narrative is a classic tool of power: divide and rule. By stating a preference for certain nationalities, the state does two things. First, it attempts to make the bitter pill of this cynical deal easier to swallow for the domestic audience. It frames the acceptance of asylum seekers not as a imposition from Washington, but as a form of pan-African “brotherhood,” a calculated appeal to regional solidarity that masks the underlying transaction. Second, and more insidiously, it establishes a category of the “other.” It implicitly creates the notion of the “bad refugee”—those from outside the continent, who can be more easily portrayed as alien, culturally disruptive, and a greater burden. This is a preemptive move to redirect future public anger away from the state and towards whichever group it designates as less desirable.

This manufactured hierarchy mirrors the same discriminatory logic the state uses to manage its own citizens. The regime has long played favourites amongst Uganda’s own diverse population, empowering some groups with political and military positions while marginalising others. The chronic neglect of indigenous communities like the Twa, who are treated as less than full citizens in their own land, is the ultimate proof of this. The state is simply applying its internal practice of creating “good” and “bad” citizens to the international stage, creating “good” and “bad” refugees. A life is not a life; it is a label to be applied for political utility.

There is a stark adage that speaks to this corrosive thinking: “Do not measure the worth of a man by the cloth of his flag, but by the content of his character.” The state, however, is doing precisely the opposite. It is measuring human worth by the passport one holds, reducing profound human tragedy—the flight from persecution, war, and despair—to a crude geopolitical calculation. It says that the suffering of a person from one side of an arbitrary line is more deserving of a chance than the suffering of a person from another. This is the antithesis of genuine solidarity, which recognises that struggle and the need for sanctuary know no borders.

This narrative is designed to make us complicit in the state’s game. It encourages us to see people not as individuals, but as categories. It asks us to accept that the state has the right to pick and choose who is worthy of safety, just as it picks and chooses which of its own citizens are worthy of investment and which are left to languish.

This narrative is designed to make us complicit in the state’s game. It encourages us to see people not as individuals, but as categories. It asks us to accept that the state has the right to pick and choose who is worthy of safety, just as it picks and chooses which of its own citizens are worthy of investment and which are left to languish.A radical response must therefore be to utterly reject this hierarchy of humanity. We must see the state’s categorisation for what it is: a strategy to control, to divide, and to deflect blame. True compassion and practical solidarity are built from the ground up, in communities that recognise a common enemy in the state that marginalises them all, and a common cause in building a world where no one is forced to flee, and where no one is deemed “bad” for having done so. Our struggle is against the borders in the mind, just as much as the borders on the map.

The Spectre of Refoulement: When Neglect Becomes a Weapon

The migration pact’s Article 3, which solemnly promises that Uganda will not return transferred individuals to danger, is a masterclass in the fiction of state legality. It offers a paper guarantee that, in practice, is utterly worthless. The true risk is not a dramatic, illegal deportation at gunpoint, but something far more insidious: indirect refoulement. This is the process whereby a state makes conditions so intolerable, or a legal process so impossibly Kafkaesque, that a person is forced to make an impossible choice: remain in a situation of destitution and despair, or return to the persecution they fled. A system that is underfunded, corrupt, and overstretched is not a failed protector; it is a highly efficient tool of expulsion.

In Uganda, the mechanisms for this indirect violence are already in place. Consider the realities for the existing refugee population: interminable delays in processing claims, a lack of competent legal aid, chronic shortages of food and water in settlements, and the constant threat of exploitation. Now, imagine introducing a new cohort of asylum seekers, with no regional ties or community support networks, into this same system. Their claims will be lost in a backlogged bureaucracy. The squalid conditions and lack of prospects will become a form of silent, psychological torture. The message will be deafeningly clear: “You are not welcome here. Your suffering is not our concern. Leave.”

This is how a state expels people while maintaining a veneer of legality. It is a strategy of deliberate neglect. The regime can point to the words in Article 3 and claim it is upholding international law, all while its officials, through a combination of malice and incompetence, are creating the conditions that force people out. This is the hypocrisy of a state that has dispossessed its own indigenous Twa people of their land and livelihood; it demonstrates a profound cruelty in its treatment of the vulnerable, whether they are citizens or not. The method is the same: make life untenable, and people will eventually move on, solving your problem for you.

This cynical practice brings to mind a piercing adage: “A government can build a wall with bricks, or it can build one with hunger.” The US-Uganda pact is building a wall of hunger. It is a wall of bureaucratic delay, of hopelessness, of calculated indifference. It is a wall that does not need to be patrolled by border guards because it is internalised in the soul of the asylum seeker, who eventually concludes that the danger they fled is preferable to the silent violence of their supposed sanctuary.

Therefore, the risk of refoulement is not a flaw in the agreement; it is its hidden feature. It is the pressure valve built into the system. When the strain of housing more people becomes too much, when diplomatic priorities shift, the state will not need to break its own laws. It can simply allow its system to fail, and the most desperate will be forced to remove themselves. The blame will fall on “a lack of resources” or “unforeseen circumstances,” deflecting it from the powerful who designed this cruel outcome from the very beginning.

This reveals that the state’s promise of protection is the coldest of comforts. It demonstrates that justice and safety can never be secured by appealing to the same powers that create insecurity. The only genuine alternative is to build communities of solidarity that operate outside of state control—networks of mutual aid that can offer real support, challenge unjust structures, and ensure that no one is ever forced to choose between a slow death by neglect and a fast one by persecution.

Strengthening the Security State: The Coil of Control Tightens

The implementation of this migration deal will not be managed by social workers or community volunteers; it will be enforced by the state’s security apparatus. This is not a side effect; it is a central, and for the regime, a desirable outcome. The agreement mandates the creation of new systems for processing, monitoring, and managing asylum seekers, which in practice means more border guards, more biometric surveillance, more checkpoints, and more administrative detention facilities. In short, this pact provides the perfect pretext for a dramatic expansion of the state’s coercive machinery, which will ultimately be used against displaced people and Ugandan citizens alike.

Every new official hired to process asylum claims, every database built to track their movements, and every new detention centre constructed in the name of “orderly management” represents a thickening of the state’s web of control. This infrastructure is never temporary or exclusive. The tools and institutions built to monitor one group of people inevitably become tools for monitoring everyone. The same biometric registration used for an asylum seeker today can be used to track a dissenting farmer or a troublesome activist tomorrow. The networks of informants cultivated in refugee settlements to report on new arrivals are the same networks used to suppress local organising.

For a regime that rules through a combination of patronage and fear, this expansion is a gift. It creates more jobs for loyalists within the security services, more contracts for connected businesses to build facilities, and more power to surveil the population. It is a self-licking ice cream cone: the state creates a problem (the social strain of new arrivals), then presents itself as the only solution, demanding more power, more funding, and more authority to deal with it. This is how a security state feeds and grows.

The cruel irony is staggering. The same state that has systematically failed to protect its most vulnerable citizens—witness the continued dispossession of the Twa people and the impunity enjoyed by those who seize land—is now investing heavily in a new security infrastructure to “protect” its borders from outsiders. It demonstrates that the state is not interested in providing genuine security in the form of welfare, healthcare, or justice; its priority is always the security of the regime itself, and this deal provides excellent cover to fortify it.

The cruel irony is staggering. The same state that has systematically failed to protect its most vulnerable citizens—witness the continued dispossession of the Twa people and the impunity enjoyed by those who seize land—is now investing heavily in a new security infrastructure to “protect” its borders from outsiders. It demonstrates that the state is not interested in providing genuine security in the form of welfare, healthcare, or justice; its priority is always the security of the regime itself, and this deal provides excellent cover to fortify it.An old adage warns of this very danger: “He who invites the soldier to his door to keep out the wolf may find the soldier never leaves, and becomes the master of the house.” By inviting in a new paradigm of internationalised security and border control to manage this deal, Uganda is inviting the soldiers. The wolf—the potential for social tension—is real, but the solution is not a force that will eventually turn its gaze inward, controlling every aspect of life. The new checkpoints, the increased police presence, and the culture of suspicion will become a permanent feature of the landscape, long after this specific deal is forgotten.

Therefore, this pact is a Trojan horse. Hidden inside the wooden horse of international cooperation and humanitarian language is an army of control. It is a catalyst for the further militarisation of Ugandan society, where the freedom of movement for all citizens becomes subordinate to the state’s obsession with monitoring and categorising people. The struggle against this deal is, fundamentally, a struggle against the very idea that our safety can be guaranteed by those who seek only to increase their power over us. True security lies in disarming this coercive apparatus, not in strengthening it.

The Silence on Root Causes: A Pact of Convenient Amnesia

The most profound deception of the US-Uganda migration agreement is not found in its clauses, but in its cavernous silence. The text meticulously outlines the mechanics of transferring human beings, but is utterly mute on the fundamental question: why are people forced to flee their homes in the first place? This is not an oversight; it is a deliberate act of erasure. The pact ensures that the role of Western powers and their allies in creating the very crises of displacement remains unexamined and unchallenged, allowing them to posture as saviours while continuing to act as architects of misery.

People do not risk everything on perilous journeys without cause. They flee wars fuelled by the international arms trade, from which permanent members of the UN Security Council profit immensely. They flee economic destitution engineered by international financial institutions that impose austerity and force open markets for corporate exploitation, draining wealth from the global South. They flee climate disasters disproportionately caused by the industrialised North, which has built its prosperity on the burning of fossil fuels. To address the flow of refugees without acknowledging these root causes is to relentlessly mop up water from an overflowing sink while ignoring the tap that is still wide open.

This silence is a political necessity for the powerful. For the United States, acknowledging its role in creating displacement would necessitate a wholesale change in its foreign and economic policy—an unthinkable prospect. It is far cheaper and easier to outsource the human consequences to a partner like Uganda, effectively paying to have the evidence of your own crimes hidden away in a remote settlement. For the Ugandan regime, this silence is equally valuable. It allows them to collect a diplomatic fee for this service without ever having to challenge the global power structures they depend on for their own survival. It is a transaction of mutual convenience built on a foundation of shared guilt.

This wilful blindness brings to mind a piercing adage: “A foolish man curses the rain flooding his hut; a wise man questions why the roof was never repaired.” This agreement is an exercise in cursing the rain. It treats refugees as a natural disaster, an inevitable downpour of human suffering to be managed. It refuses to look up and see that the roof has been deliberately dismantled over decades by policies of extraction and domination. The powerful are the ones who stripped the roof, and now they are selling us buckets to bail out the water.

In the Ugandan context, this is a familiar story. The state itself routinely ignores the root causes of its own internal crises. The deep poverty that drives Ugandans into precarious informal work is never addressed by tackling the rampant corruption and inequality that cause it. The marginalisation of the Twa people is treated as an unfortunate fact of life, not as a direct result of state-sanctioned land grabs and cultural erasure. The government, itself a product of a system that ignores root causes, is the perfect partner for an international community that wishes to do the same.

Therefore, this pact is a monument to hypocrisy. It is a agreement to manage the symptoms of a disease that the signatories are actively spreading. Any genuine approach to human movement would begin by dismantling the machinery of war, economic exploitation, and ecological plunder. The fact that this agreement does not even mention these issues proves that it is not a solution, but a cynical containment strategy. It confirms that we cannot expect those in power to solve the problems they create. Our focus must shift from appealing to them to building our own power from below, creating communities of solidarity that recognise our common enemy in these oppressive systems and our common cause in a world without borders, where people are free to stay rather than being forced to flee.

Therefore, this pact is a monument to hypocrisy. It is a agreement to manage the symptoms of a disease that the signatories are actively spreading. Any genuine approach to human movement would begin by dismantling the machinery of war, economic exploitation, and ecological plunder. The fact that this agreement does not even mention these issues proves that it is not a solution, but a cynical containment strategy. It confirms that we cannot expect those in power to solve the problems they create. Our focus must shift from appealing to them to building our own power from below, creating communities of solidarity that recognise our common enemy in these oppressive systems and our common cause in a world without borders, where people are free to stay rather than being forced to flee.Community Solidarity vs. State Imposition: The Co-option of Compassion

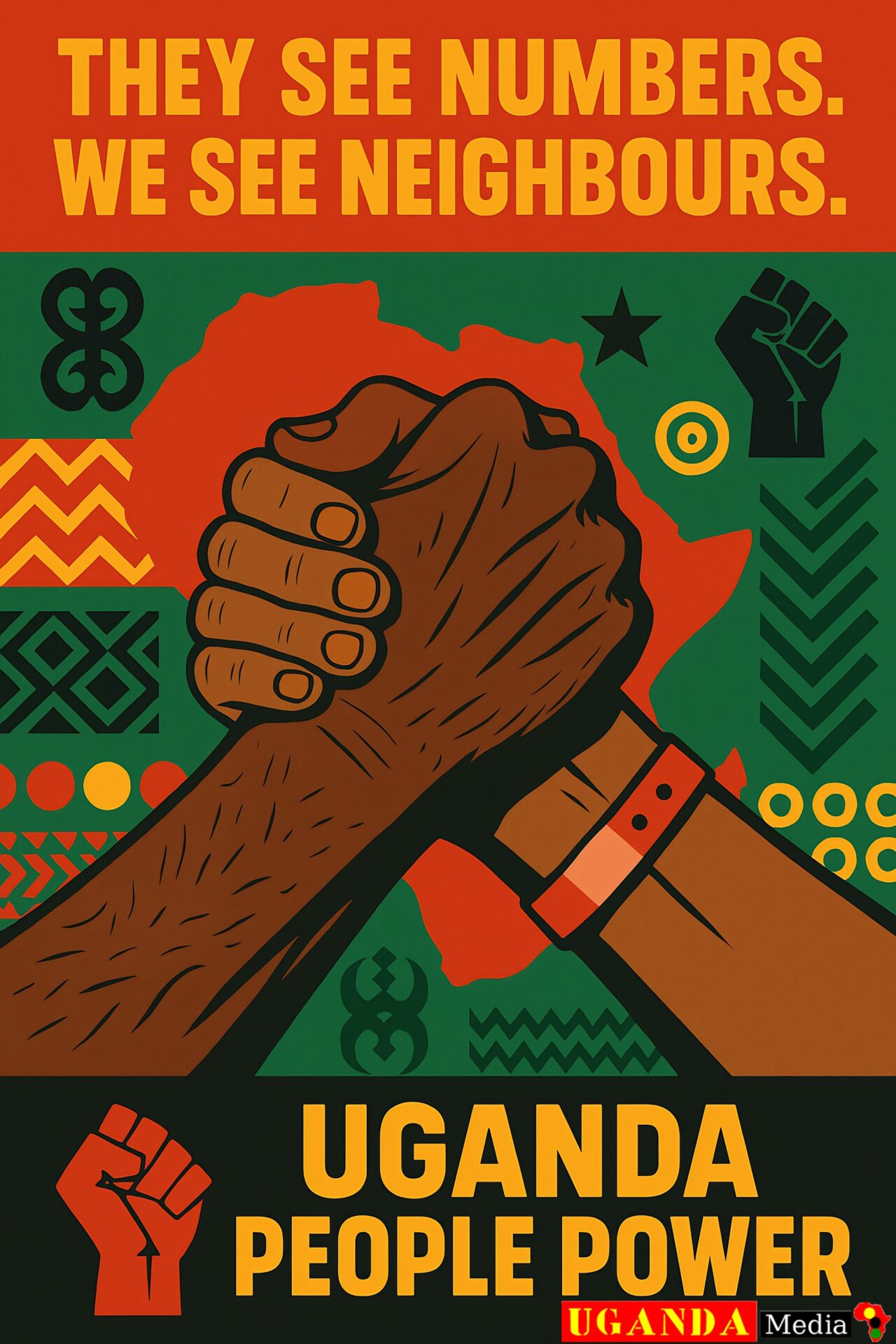

For decades, the true story of Uganda’s refugee response has not been written by the state, but by its people. In borderland communities across the north and west, ordinary Ugandans have shared their land, their water, and their meagre resources with those fleeing neighbouring wars and persecution. This profound acts of solidarity, of genuine human-to-human mutual aid, stands in the starkest possible contrast to the cold, top-down transaction just signed in Kampala. The state, recognising the power and moral authority of this organic compassion, is now seeking to co-opt it, to corrupt it into a tool for its own political and diplomatic gain.

This historical community solidarity operates on a logic utterly foreign to the state. It is horizontal, voluntary, and based on a shared understanding of struggle. A family that has known hunger does not need a government decree to understand the plight of someone with nothing. They act. They see a person, not a case file; a neighbour in need, not a geopolitical bargaining chip. This is a self-organised resilience that has saved countless lives and built fragile, yet real, bonds across cultures and nationalities.

The state’s new deal represents the opposite: a vertical, imposed, and coercive model. It is not born from compassion but from calculation. The regime did not consult the communities in Nakivale or Kyaka II; it consulted its balance of trade with Washington. By draping this cynical transaction in the language of Uganda’s “generous” refugee policy, the state performs a vicious sleight of hand. It steals the moral credit earned by the everyday generosity of its citizens and uses it to launder a deal that serves only the powerful. The state, which has historically been absent in providing meaningful support to these host communities, now arrives with a plan that will further strain their resources, all while claiming the mantle of their humanitarian spirit.

This is the ultimate corruption of power. It takes something beautiful and organic—the human impulse to help another—and attempts to bureaucratise it, to turn it into a regulated, managed system that reinforces the state’s authority. It is like watching a bureaucrat try to put a river into a pipe; he may redirect the water for his own purposes, but he kills everything that gave it life and force in the process.

An adage speaks directly to this conflict: “The hand that offers a sweet potato from its own garden does a greater service than the king who signs a decree to empty the granary.” The first act is one of direct, genuine solidarity. The second is an act of abstraction and control, often using resources it did not grow and will not miss. The Ugandan state is now the king, signing a decree that will empty the granaries of its own people, all while posing as a great benefactor.

This imposition threatens to poison the very wellspring of community solidarity it claims to champion. When new arrivals are parachuted in as part of a distant political deal, rather than arriving through regional patterns of flight, it can breed resentment. The state, by creating this tension, then positions itself as the indispensable mediator, the necessary authority to manage the conflict it itself created. It first exploits solidarity, then suppresses the natural social friction that results from its own actions, all to justify its own expanded control.

Therefore, the fight is to reclaim solidarity from the state. It is to recognise that our power lies not in appealing to the ministries in Kampala, but in strengthening the bonds of mutual aid that already exist between us. It is to protect the authentic, voluntary compassion of the community from the corrupting, self-serving imposition of power. True refuge is not, and can never be, administered by the state. It is built by people, for people, on the simple, radical principle that we will care for one another because it is the right thing to do.

A Blueprint for Further Outsourcing: The Normalisation of Abandonment

The true danger of the US-Uganda migration pact extends far beyond its immediate impact. Its greatest threat lies in its function as a prototype, a testing ground for a new and brutal form of global apartheid. If this arrangement is deemed a “success” by Washington—meaning it efficiently removes unwanted asylum seekers without causing a major diplomatic scandal—it will undoubtedly become a model. This pact is the first stitch in a tapestry of outsourcing, where the world’s wealthy and powerful nations can pay to dump their humanitarian and legal responsibilities onto poorer, more compliant states, effectively purchasing their own moral absolution.

This creates a ready-made market for human suffering. For regimes facing economic isolation or seeking geopolitical favour, like Uganda’s, the ability to rent out their sovereignty and their people’s resilience becomes a new commodity. They can offer themselves as a solution to the West’s so-called “migration crisis,” turning their territory into a kind of offshore human warehouse. This turns the global South into a dumping ground for the consequences of wars and economic policies authored in the global North, all while the perpetrators maintain a clean conscience and secure borders.

Uganda, in this grim calculus, is the perfect pilot project. Its government’s need for international rehabilitation after the AGOA suspension makes it compliant. Its existing refugee framework provides a fig leaf of legitimacy. And its distance from the United States ensures the process is out of sight and out of mind for American voters. If it works here, why not replicate it with other nations? Why wouldn’t the UK, or Canada, or EU members seek similar deals with other countries desperate for aid or trade concessions? This pact signals that the right to seek asylum—a universal human right—is now becoming a privilege that can be subcontracted to the lowest bidder.

This establishes a terrifying hierarchy of humanity. The value of a person’s safety will no longer be determined by the merit of their claim, but by the capacity of their country of origin to disrupt the West. Those from nations deemed too problematic to handle directly will be processed in distant, underfunded camps, while a select few might still reach foreign shores. It is the ultimate expression of a world where everything, including justice, is privatised and outsourced for convenience.

This cynical strategy brings to mind a stark adage: “When the first goat willingly crosses the rusty bridge, the butcher knows the rest will follow.” Uganda is the first goat. By normalising this practice, it makes it easier for other nations to be pressured into similar arrangements, each one further eroding the very principle of international protection. The bridge may be rusty and dangerous, but the promise of a temporary feed from the butcher is enough to lure others across, sealing their fate and that of countless vulnerable people.

For the common Ugandan, this blueprint offers nothing. It does not bring development that benefits the many, only contracts that enrich the few. It brings more strain on resources and the ever-expanding apparatus of state control. It signals that their country is being used as a laboratory for a global experiment in responsibility-shirking.

For the common Ugandan, this blueprint offers nothing. It does not bring development that benefits the many, only contracts that enrich the few. It brings more strain on resources and the ever-expanding apparatus of state control. It signals that their country is being used as a laboratory for a global experiment in responsibility-shirking.Therefore, resisting this pact is about more than just this one agreement; it is about fighting a nascent global system designed to make the right to asylum meaningless. It is a struggle against the creation of a world where the powerful can literally pay to have their problems disappear into the hinterlands of poorer nations, leaving the displaced in a legal limbo and host communities to bear the burden. Our opposition must be fierce and unequivocal, recognising that an injury to one, in this case, is an injury to all. We must reject the very notion that survival is a commodity to be traded and that safety is a privilege that can be outsourced.

The Fiction of “Temporary”: The Architecture of a Permanent Crisis

The Ugandan state’s description of this migration arrangement as “temporary” is a deliberate and strategic fiction, a soothing lie designed to dull the sharp edge of a permanent change. In the grim theatre of power, there is no such thing as a temporary structure of control. What begins as an “interim measure” or a “pilot project” has a habit of calcifying into a permanent fixture, creating a self-perpetuating system that becomes impossible to dismantle. This agreement is not a fleeting exception; it is the laying of a foundation for a new, enduring architecture of state power and global injustice.

The state is a master of this tactic. It declares a “temporary” state of emergency to quell dissent, which then justifies the permanent expansion of security laws. It initiates a “temporary” economic project that dispossesses people of their land, which then becomes a fait accompli. The same logic applies here. The bureaucracies, databases, and detention centres established to manage this deal will not simply vanish once the agreement is terminated. They will remain, like a new organ in the body of the state, seeking a new purpose. The officials hired will protect their jobs. The security companies hired to guard facilities will lobby for new contracts. The entire apparatus will find new populations to manage, new reasons for its own existence, long after the last transferred asylum seeker has left.

This creates a dangerous inertia. The very existence of this system will create a demand for its use. Having invested in the infrastructure, the US will be incentivised to continue and even expand the transfers. For the Ugandan regime, this “temporary” system becomes a permanent source of leverage, a diplomatic chip it can cash in with Western nations for years to come. It transforms a nation’s sovereignty into a service industry for rent.

This fiction is particularly grotesque when contrasted with the state’s treatment of its indigenous people. The marginalisation of communities like the Twa is never described as a “temporary” situation; it is a permanent condition of their existence, engineered by state policy and indifference. The state is adept at making its neglect permanent for the powerless, while offering the illusion of temporariness for its own convenient and damaging schemes.

A piercing adage warns us of this very reality: “Beware the doorway built for a guest, for it remains long after they have left, and others will use it to enter uninvited.” This pact is that doorway. It is being framed as a specific entrance for a specific, limited number of people. But the doorway itself—the legal framework, the security arrangements, the normalisation of human transfers—will remain. It will be used again. It sets a precedent that the movement of people can be managed like a supply chain, and that some nations can become global holding pens. Once this principle is accepted, it is only a matter of time before the scope is widened.

Therefore, to accept the label of “temporary” is to be complicit in a long-term project of control. It is a strategic deception designed to bypass serious scrutiny and opposition. The time to resist is now, before the concrete sets and the structure becomes a permanent part of the landscape. Our struggle is against the very creation of these systems, because we understand that power never voluntarily dismantles the tools it has built to sustain itself. The temporary is a Trojan horse for the permanent, and we must see it for what it is: a lie designed to make a dangerous future more palatable in the present.

The Distraction from Domestic Failures: A Performance of Toughness

For the United States, this migration pact with Uganda is not a solution; it is a spectacular piece of political theatre. It is a carefully staged performance designed to create the illusion of toughness and control over immigration, while utterly failing to address the grotesque inefficiencies, profound injustices, and deep-rooted cruelty of its own asylum system. This deal is a distraction, a magician’s trick that directs the audience’s gaze away from domestic failure and towards a flashy, outsourced spectacle.

The US asylum system is a labyrinth of deliberate delay, a monument to bureaucratic barbarism where claims can take years to process, leaving people in devastating limbo. It is a system where profit-driven detention centres warehouse human beings, and where the outcome of a case can hinge more on the mood of an official or the skill of an overworked lawyer than on the merit of the claim. To fix this would require a radical overhaul: dismantling the detention industry, hiring a small army of caseworkers and judges, and confronting the nation’s role in creating the conditions that force people to flee. This would be expensive, politically challenging, and would require a genuine reckoning with American foreign policy.

This deal is the opposite of that. It is the easy way out. It is a cheap, cynical workaround that allows US politicians to pose as decisive leaders who are “getting a grip” on immigration, without doing the hard work of reform. By proposing to ship the “problem” thousands of miles away to Africa, they can tell their constituents they have taken action, all while the fundamentally broken and inhumane system at home continues to grind on uninterrupted. The human consequences are simply made invisible, offshored to a continent where they will attract far less media scrutiny.

This is a classic strategy of power: export your crises. Just as the Global North has long exported its pollution and its exploitative labour practices to the South, it now seeks to export the human fallout from its wars and economic policies. The US, a primary architect of global instability, is now subcontracting the management of its victims. It is the ultimate act of hypocrisy, dressed up as international cooperation.

This manoeuvre brings to mind a stark adage: “A bad workman always blames his tools, but a cunning one hides the broken tools and hires a foreign carpenter to take the blame.” The US political class are the cunning workmen. Their tools—the asylum system—are not just broken; they are designed to fail. Rather than fix them, they have made a show of hiring a foreign carpenter—the Ugandan regime—to take over the job, ensuring that when the shelf collapses, the blame will fall on Kampala’s workmanship, not on the original flawed design.

For the Ugandan regime, this role is perfectly suited. It gets to perform on a world stage and extract diplomatic concessions, all while the actual suffering is borne by its own overburdened communities. It is a pact between two powers, each seeking to use human beings as political props to distract from their own failings—the US from its immoral system, and Uganda from its chronic neglect of its own people, such as the Twa.

Therefore, this deal is a testament to cowardice and the avoidance of responsibility. It proves that powerful states would rather invent elaborate, cruel schemes to hide their problems than address them with justice and humanity. Our solidarity must be with the people caught in this cynical game—the asylum seekers being used as pawns and the communities being set up to fail. We must see this distraction for what it is and demand real, rooted solutions that address the causes of displacement, rather than perpetuating a global shell game with human lives.

The Erosion of Local Autonomy: The Dictatorship of Distance

The most insidious violence of the US-Uganda migration pact is the absolute disregard it shows for the people who will bear its consequences. The question of how host communities—those already struggling under the weight of immense pressure—will be consulted is answered by the silence of the document itself. They will not be. This deal is the ultimate expression of the dictatorship of distance: a decision made in the air-conditioned rooms of Kampala and Washington, imposed with cold indifference upon the villages and settlements on the front line.

For the communities bordering settlements like Kyaka II or Nakivale, life is a daily negotiation with scarcity. Water, firewood, grazing land, and school places are finite resources, and the delicate social fabric is maintained through continuous, grassroots dialogue and mutual understanding. This organic, local self-management is the very antithesis of how the state operates. The state does not seek consent; it issues decrees. It does not build consensus; it imposes its will. This pact is a declaration that the people of these regions are not citizens with a voice, but subjects to be commanded, and their land is not a home to be cherished, but a dumping ground to be utilised.

This erasure of local autonomy is a familiar story. The same centralised power that allocated Twa ancestral land to logging companies and conservation projects without their consent is the same power that now allocates entire districts to a new international policy. The regime’s habit of privileging the demands of foreign capital and diplomatic convenience over the needs of its own people is simply being applied to a new domain. The individual Ugandan citizen, whether from Kasese or Adjumani, is the last consideration in a calculation about prestige and leverage between national elites.

This erasure of local autonomy is a familiar story. The same centralised power that allocated Twa ancestral land to logging companies and conservation projects without their consent is the same power that now allocates entire districts to a new international policy. The regime’s habit of privileging the demands of foreign capital and diplomatic convenience over the needs of its own people is simply being applied to a new domain. The individual Ugandan citizen, whether from Kasese or Adjumani, is the last consideration in a calculation about prestige and leverage between national elites.This dynamic is perfectly captured by a piercing adage: “When the axe came into the forest, the trees said the handle is one of us.” The Ugandan state, which should be the representative of its people, is the handle of the axe. It is made from the same wood as the communities it is poised to strike. Yet, in its allegiance to a more powerful foreign force, it turns against its own. The blow to local autonomy and well-being will be delivered by a government that claims to speak for the nation, while acting entirely against the interests of its most vulnerable constituents.

Therefore, this deal is not just about migration; it is about the very nature of power. It demonstrates that centralised state power, by its very nature, is hostile to local self-determination. It cannot help but override it. The people of Bidi Bidi or Rwamwanja are not expected to have a say; they are expected to absorb the shock. This creates a dangerous powder keg of resentment, which the state will then inevitably manage not with dialogue or support, but with increased policing and control, further eroding the very autonomy it stole.

The radical response to this is not to plead for a seat at the table in Kampala. It is to build power from below. It is to strengthen the local assemblies, the co-operative structures, and the networks of mutual aid that can act as a buffer against these distant edicts. It is to recognise that our true strength lies in our ability to organise our own communities according to our own needs, and to present a united front of refusal to any plan made over our heads and against our interests. Our autonomy is not something to be granted by the state; it is something we must seize and defend for ourselves.

The Profit of a Few: The Banquet of the Connected

Beneath the lofty language of international cooperation and humanitarian duty lies the grim, unshakeable truth of state power: it is, and has always been, a lucrative franchise for the well-connected. This migration pact, like all major state projects, is not an exception; it is a textbook example. While the rhetoric speaks of shared burdens and protection, the reality is that a handful of elites are already sharpening their knives, ready to carve up the spoils. This deal is not primarily about managing people; it is a potential bonanza for those who count themselves amongst the regime’s favoured circle.

Ask the simple, revealing questions that power hopes we will ignore: Who will secure the multi-million-dollar contracts to build the new detention and processing facilities? Who will win the tenders to supply them with food, bedding, and security? Which ‘non-governmental’ organisations, headed by former ministers or relatives of generals, will be granted the lucrative contracts to ‘manage’ the incoming funds and administer the programmes? The answers will not be found in a public, competitive bidding process that benefits the most efficient or compassionate provider. They will be decided in shadowy backrooms and whispered over phones, a familiar circuit of patronage where contracts are rewards for loyalty, not instruments for effective service.

This is the true economy of the state. It operates a constant transfer of wealth from the public coffers—from the taxes of the struggling citizen and the funds of foreign donors—into the private bank accounts of a select few. The same system that allocates vast tracts of public land to cronies is the same system that will now allocate human beings to facilities built by those very same cronies. The profound suffering of the displaced and the genuine solidarity of host communities are merely the raw materials in this grisly production line, inputs to be converted into profit for those who already have far more than they need.

An old adage, known in many cultures, lays this bare: “Where the carcass lies, there the vultures will gather.” The state, by creating this new programme, is strategically placing a carcass—a massive infusion of foreign cash and resources—onto the landscape. The vultures—the contractors, the suppliers, the consultants, the bureaucrats—are already circling. They are not there to help; they are there to feed. They will feast on misery, growing fat on contracts that will be inflated, services that will be substandard, and funds that will be mysteriously diverted, while the intended beneficiaries—both asylum seekers and Ugandan citizens—receive the barest scraps.

This exposes the fundamental lie that the state acts for the common good. It acts for its own good and for the good of its network. The chronic neglect of the Twa people, for instance, is not an accident of limited resources; it is a deliberate choice. Resources are not allocated to those in greatest need, but to those who offer the greatest political utility. A community that cannot get a decent road or a functioning clinic will now watch as millions are spent on a new security infrastructure to manage outsiders, an infrastructure that will inevitably line the pockets of the already powerful.

This exposes the fundamental lie that the state acts for the common good. It acts for its own good and for the good of its network. The chronic neglect of the Twa people, for instance, is not an accident of limited resources; it is a deliberate choice. Resources are not allocated to those in greatest need, but to those who offer the greatest political utility. A community that cannot get a decent road or a functioning clinic will now watch as millions are spent on a new security infrastructure to manage outsiders, an infrastructure that will inevitably line the pockets of the already powerful.Therefore, to oppose this pact is to oppose this grand theft. It is to recognise that the state is not a neutral manager but a vehicle for elite accumulation. Our struggle is against this entire system of organised corruption. It is a fight for a world where resources are managed collectively by communities for the benefit of all, where no one profits from the suffering of others, and where the concept of turning human misery into a business opportunity is seen for what it is: a profound and unforgivable crime.

The Inevitability of a Backlash: The State’s Engine of Division

The most predictable outcome of this migration pact is not its success or failure, but the backlash it will deliberately manufacture. When the inevitable strain of additional arrivals exacerbates the existing crisis of scarce resources, the state will not accept responsibility. It never does. Instead, it will expertly redirect the rising tide of popular frustration away from its own door and towards two convenient scapegoats: the newly arrived refugees and the Western powers that sent them. This is a calculated strategy to divide people who share a common enemy in a neglectful and exploitative system, ensuring they fight amongst themselves rather uniting against their true oppressor.

The state’s playbook is well-worn. When a clinic has no medicines, when a water point runs dry, or when a job is given to a newcomer, the government’s narrative will not focus on its own historic failure to build a robust health system, ensure water security, or create a functioning economy for its citizens. It will subtly, or not so subtly, point to the “new burden” it was “forced” to accept. The anger that should be directed at the ministries in Kampala for chronic underinvestment will be misdirected towards the asylum seeker in the settlement or the diplomat in Washington. This is how a state that has abandoned its own indigenous people, like the Twa, to generations of neglect, maintains its power: by ensuring the dispossessed never recognise their shared dispossession.

This is the oldest trick of power: divide and rule. By pitting the urban poor against the rural farmer, the landless labourer against the struggling refugee, the state fractures the possibility of a united front. A population busy suspecting and resenting its neighbour is a population that is not organising to demand accountability from its rulers. The state, which created the conditions of scarcity through its corruption and mismanagement, then positions itself as the only force capable of policing the social tensions it engineered.

A profound adage captures this cynical manoeuvre: “A clever man never blames the axe for the fallen tree, but the hand that swings it.” In this case, the state is both the cunning man and the hand. It is swinging the axe of economic neglect and political exclusion, chopping down the forest of communal solidarity. Then, it drops the axe—the asylum seeker—and encourages everyone to blame the tool for the destruction, all while its own hand remains hidden. The refugee, like the axe, is an instrument, not the architect, of the crisis.

For the ordinary Ugandan and the asylum seeker alike, this is a trap. They are being set on a collision course by a third party that will then step in to “manage” the conflict it created, further consolidating its control with more police, more restrictions, and more rhetoric about maintaining order. The real cause of the suffering—a state that serves the interests of a tiny elite at the expense of the vast majority—is allowed to escape scrutiny.

Therefore, recognising this inevitability is the first step towards resisting it. Our struggle must be to see through this manipulation and to build solidarity across these imposed divides. We must understand that the struggle of a Ugandan mother for water is the same as the struggle of a refugee mother for safety. Both are victims of the same system of power that values political leverage and private profit over human life. Our resistance must be to unite against the hand that swings the axe, not to fight over the tools it discards. True power lies in refusing to play the state’s game and instead building a common cause based on our shared need for dignity, autonomy, and justice.

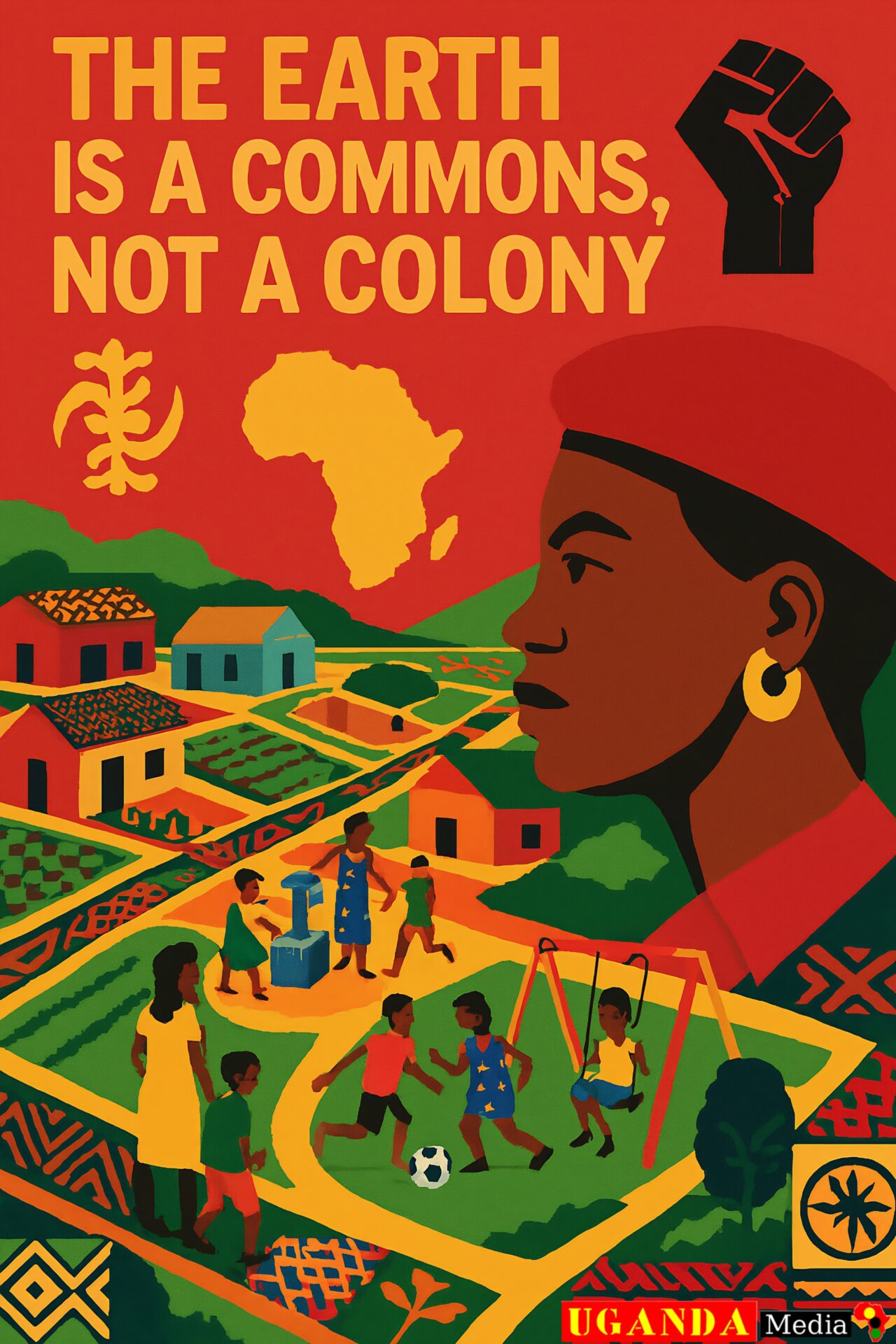

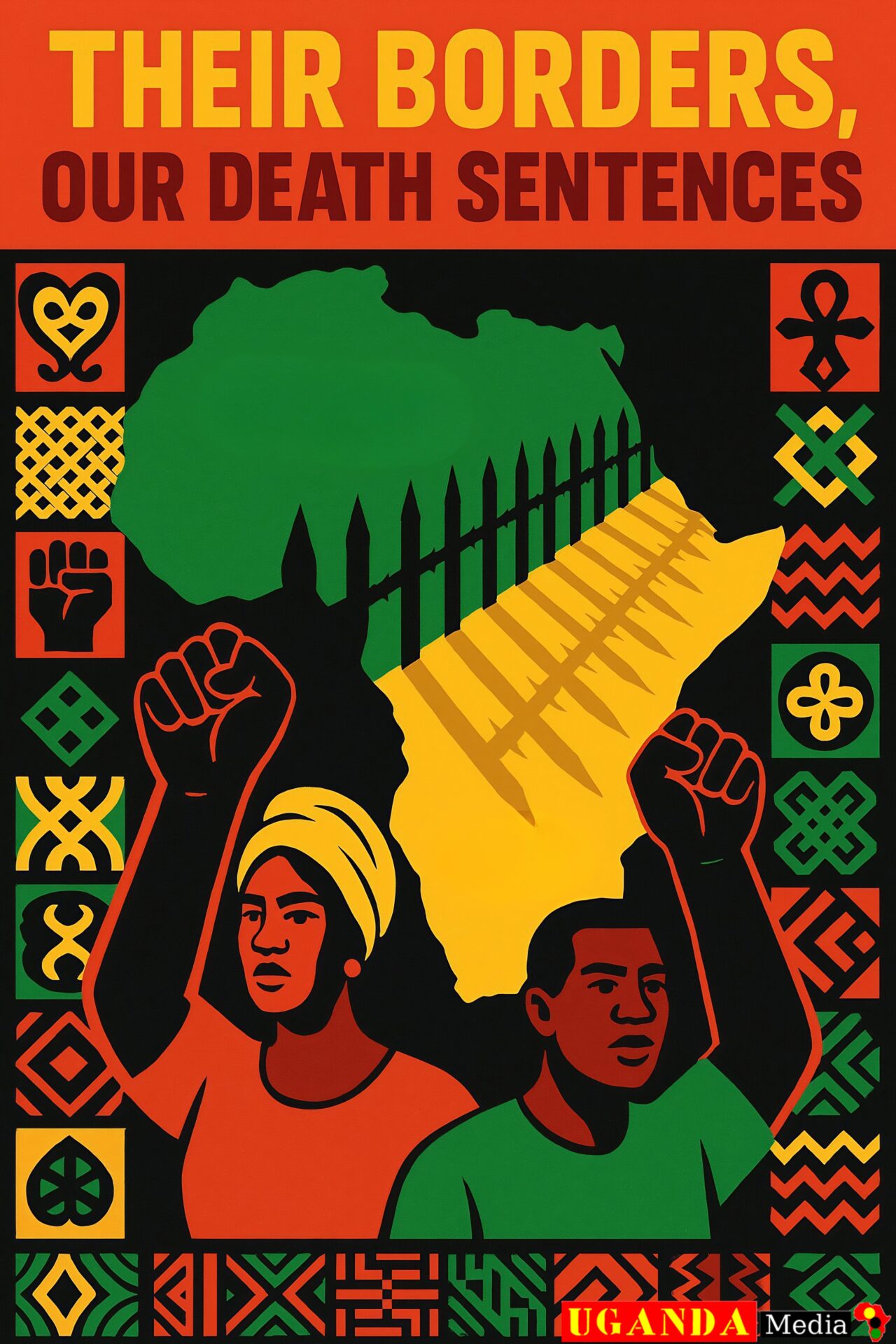

The Alternative of Abolishing Borders: Towards a Philosophy of Shared Earth

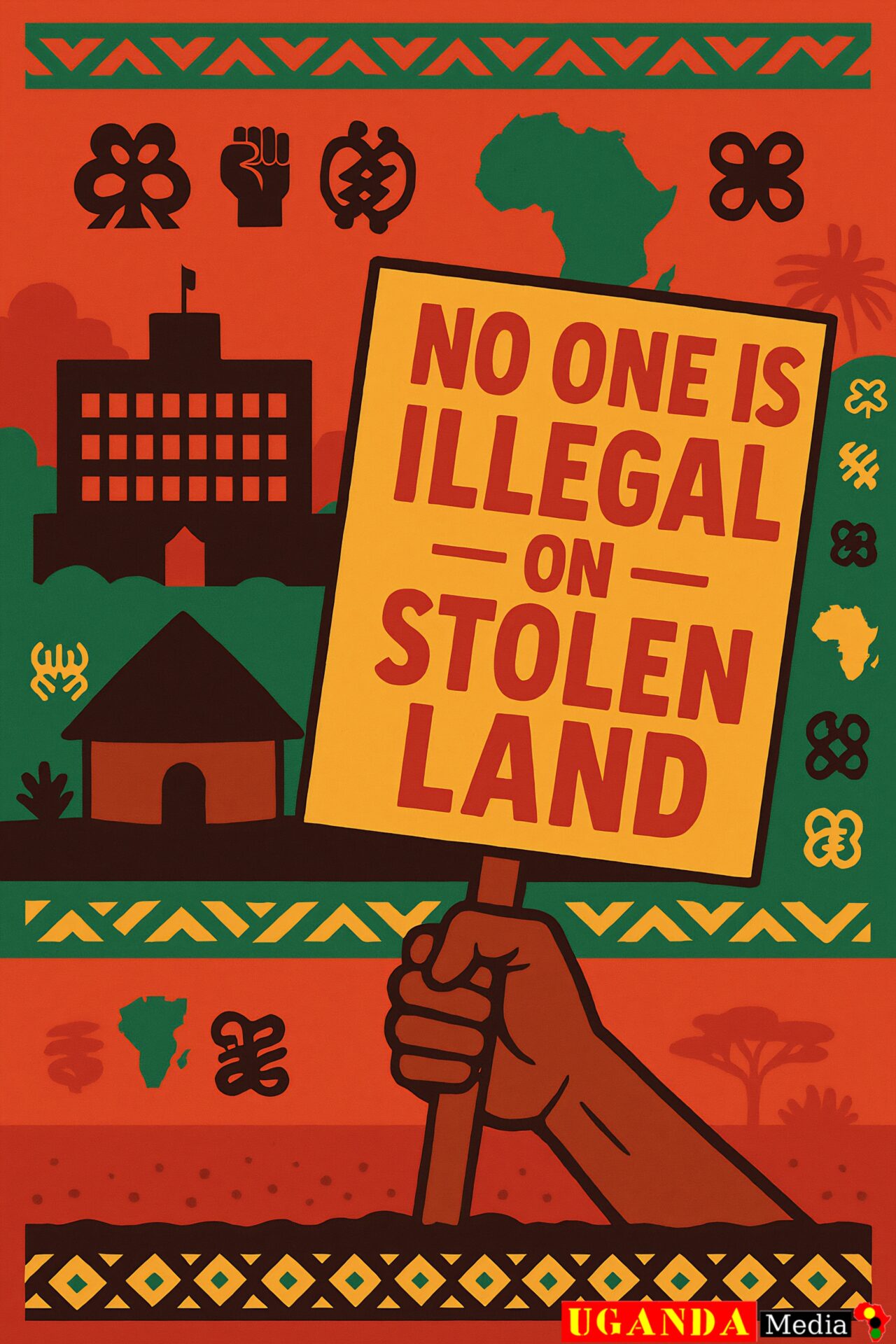

The most radical, and indeed the most practical, response to the cruel spectacle of the US-Uganda migration pact is not to tinker with its clauses or to plead for a more humane management of its terms. It is to confront the very source of the injustice: the violent fiction of the border itself. We must have the courage to question the legitimacy of these artificial lines—drawn by colonisers in distant European capitals—that serve primarily to divide the global working class and protect the obscene wealth and security of a tiny, transnational minority.

Borders are not natural features of our world; they are political tools. In East Africa, they arbitrarily split communities, languages, and cultures that have existed for millennia. They are the reason, a person from Kigezi may feel more connection to a kinsman in Rwanda than to a government official in Kampala. These lines on a map are maintained not for our benefit, but for the benefit of the powerful. For the rich, borders are a convenience; they can cross them with ease, investing capital and extracting resources wherever they please. For the poor, they are a cage, designed to confine them to zones of exploitation and scarcity, and to turn them against their neighbours who are trapped in identical cages next door.

The state enforces these borders with violence because it is the ultimate guarantor of this unequal system. The same regime that neglects the Twa people—Uganda’s first citizens, who knew no borders—will deploy soldiers to patrol a line that meaninglessly cuts across their ancestral lands. This is the ultimate absurdity: a state that fails to provide for its people will fight to the death to control the dirt upon which they stand, not to protect them, but to define them as a taxable, controllable population.

This system brings to mind a powerful adage: “A river does not drink its own water; a tree does not eat its own fruit.” The natural world operates on principles of sharing and circulation. Borders are the human attempt to defy this logic, to hoard the fruit and dam the river for the benefit of a select few. They create artificial scarcity where none need exist, forcing us to see the arrival of another human being not as a potential collaborator or neighbour, but as a threat to our allocated share of misery.

This system brings to mind a powerful adage: “A river does not drink its own water; a tree does not eat its own fruit.” The natural world operates on principles of sharing and circulation. Borders are the human attempt to defy this logic, to hoard the fruit and dam the river for the benefit of a select few. They create artificial scarcity where none need exist, forcing us to see the arrival of another human being not as a potential collaborator or neighbour, but as a threat to our allocated share of misery.The alternative is not some utopian fantasy; it is the practical recognition of a shared reality. Our struggles are interconnected. The poverty of a farmer in Nebbi is linked to the policies of financial institutions in Washington and London. The war that forces someone to flee the Democratic Republic of Congo is often fuelled by the mineral wealth demanded by our phones and gadgets. We are already bound together in a global system, but one designed for exploitation. We must build a new one based on solidarity.

Abolishing borders does not mean an end to community or belonging. It means expanding the concept of the community to its natural limits. It means organising our societies from the bottom up, based on voluntary association and mutual aid, rather than top-down dictation by a state that serves capital. It means recognising that the right to move, to seek safety, and to build a better life is a fundamental right that precedes any law written by man. Our true security does not lie in fences and passports, but in strong, self-governed communities that are free to connect with the wider world, sharing knowledge, resources, and hospitality without the interference of a coercive state that profits from our division. This is not a dream; it is the only logical conclusion for those who seek a world built on justice, not lines in the sand.

Power Reveals Itself: The Mask Is Off

The US-Uganda migration pact is not some strange anomaly or an isolated misstep in governance. It is a perfect, crystalline lesson in the true nature of state power. It is a moment of shocking clarity, where the mask slips entirely, revealing the cold, mechanical face of authority beneath. This deal demonstrates, with textbook precision, how power actually operates: through secretive agreements made over the heads of the people, the calculated sacrifice of human dignity for political gain, and the ruthless maintenance of control by turning us against one another.