From Arua to Kampala: The Lugbara Identity in a Globalised World

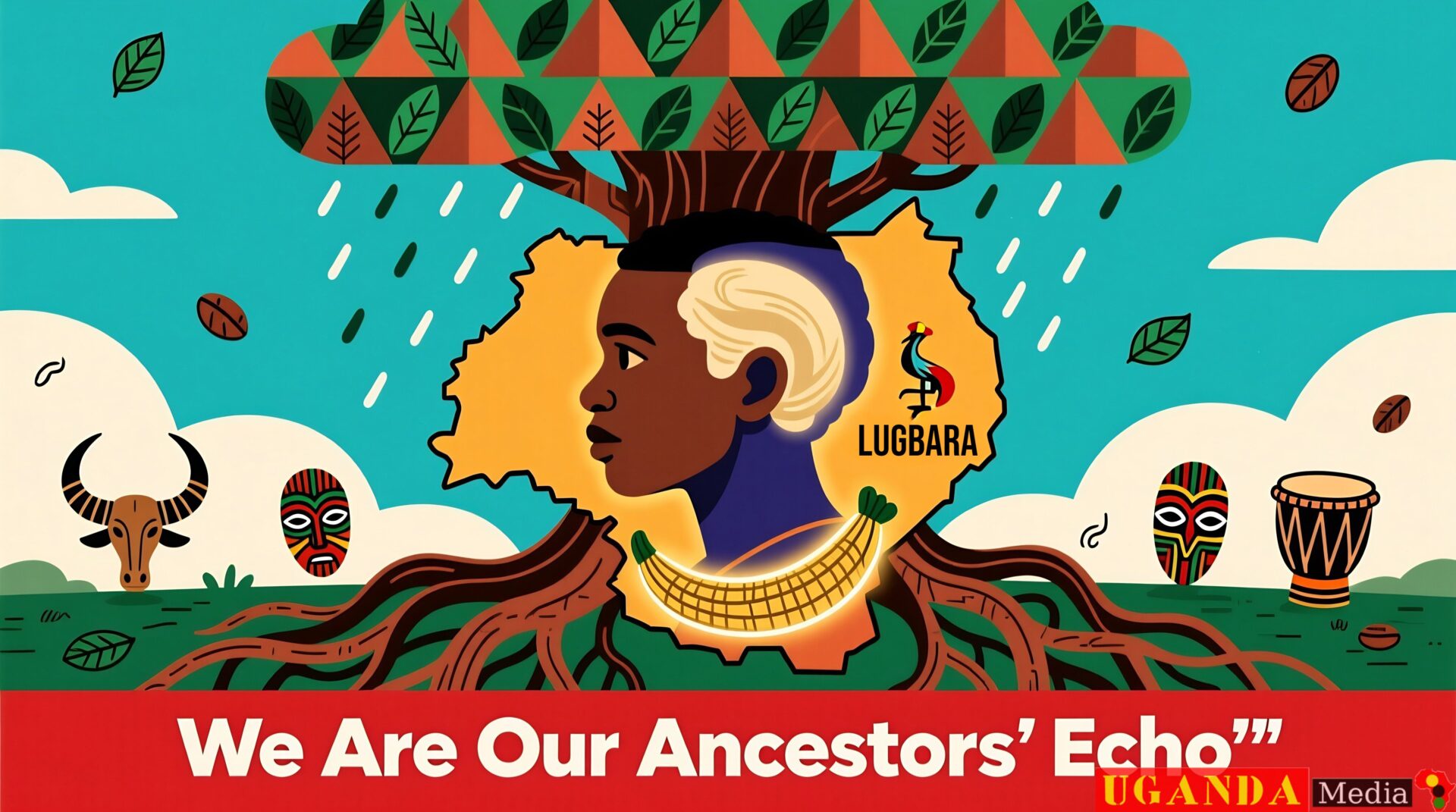

Nestled in the verdant hills and fertile plains of North-Western Uganda and the South Sudan borderlands, the Lugbara people have cultivated a cultural heritage of extraordinary depth and resilience. For centuries, their world has been orchestrated as a profound dialogue between the living, the ancestors, and the natural environment—a holistic system where spirituality, community, and ecology are inextricably linked. This comprehensive exploration delves into the very heart of Lugbara identity, from their Sudanic linguistic roots and epic migration histories to the intricate rituals that continue to define their way of life.

Discover the solemn power of the opi-ozogo dri (rain-maker) and the sacred otuke stones, practices that blend keen environmental observation with spiritual reverence. Understand the communal fabric woven through vibrant marriage processions, the ethical guidance sought through divination practices like Büro and Qbagba, and the solemn rites of passage that connect each individual to the ancestral continuum presided over by Adroa, the Great Spirit.

Yet, the Lugbara narrative is not one frozen in time. It is a dynamic story of adaptation and preservation. This guide also confronts the pressing challenges of urbanisation, globalisation, and cultural change, examining how the tribe navigates the tension between tradition and modernity. We highlight the vital efforts to document their language and oral histories (Adi), and the vibrant festivals revitalising pride among the youth.

Ultimately, the story of the Lugbara offers more than an anthropological insight; it provides timely lessons in communal solidarity, sustainable living, and the search for meaning. Join us in uncovering the enduring legacy of one of East Africa’s most fascinating peoples, whose ancient echoes powerfully guide the quest for a connected and resilient future.

Twenty Key Explorations into Lugbara Life and Legacy

The Historical Crucible: Forged in Movement, Defined by Home

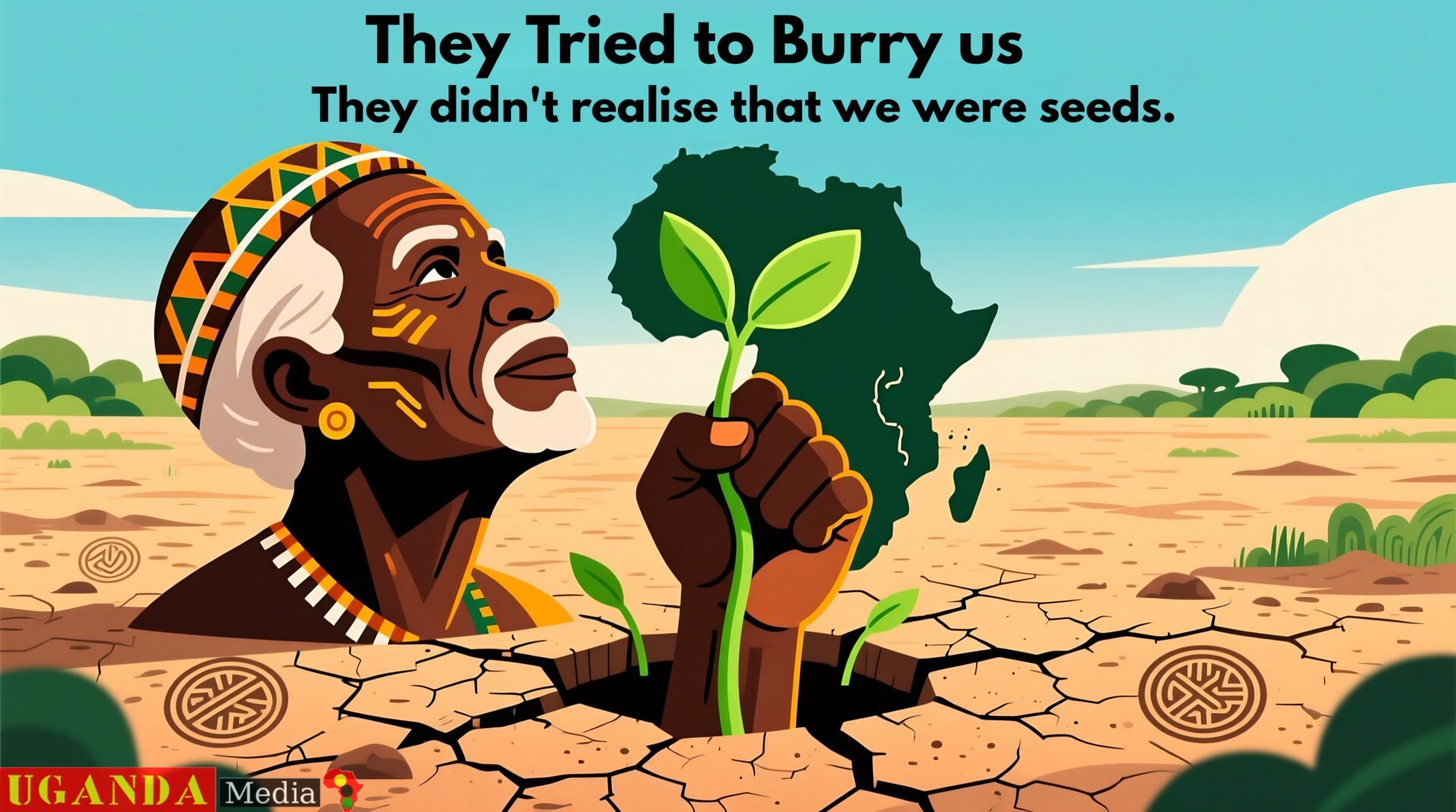

The story of the Lugbara people cannot be told from a fixed point on a map. It is a narrative etched in movement, a testament to the ancient adage that “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.” Their history is a crucible—a searing journey of displacement, adaptation, and eventual synthesis—where a distinct identity was forged not in the comfort of a single, eternal homeland, but in the arduous process of seeking one. To understand the Lugbara of north-western Uganda today is to trace their ancestral footsteps back to the north-west, a saga of resilience that transformed migrants into stewards of a new land.

This foundational migration was not a single, organised exodus but a series of population movements, likely occurring over centuries and propelled by the classic drivers of pre-colonial African history: the search for arable land, pressure from other expanding groups, and the simple, human desire for stability. Oral histories and linguistic evidence place their origins within the broader Sudanic-speaking peoples, linking them ethnically and philologically to groups like the Moru and Logo, now primarily found in South Sudan and the north-eastern Democratic Republic of Congo.

The journey southwards is remembered in folklore as a parting of ways at a mythical place, often called “Kolo” or “Lulu.” This symbolic fork in the road represents the moment the proto-Lugbara diverged from their linguistic cousins. From this point, the migration splintered into what scholars identify as two main streams. One group travelled a more westerly route, navigating the dense landscapes that fringe the Congo Basin, before finally settling in the areas that now constitute Arua District and the wider West Nile region of Uganda. Another group took an eastern path, believed to have crossed the Kaya River near the area of Arube. These were not armies on the march, but likely kin-based clans moving with their livestock, seeds, and sacred objects, their progress measured in generations.

The journey southwards is remembered in folklore as a parting of ways at a mythical place, often called “Kolo” or “Lulu.” This symbolic fork in the road represents the moment the proto-Lugbara diverged from their linguistic cousins. From this point, the migration splintered into what scholars identify as two main streams. One group travelled a more westerly route, navigating the dense landscapes that fringe the Congo Basin, before finally settling in the areas that now constitute Arua District and the wider West Nile region of Uganda. Another group took an eastern path, believed to have crossed the Kaya River near the area of Arube. These were not armies on the march, but likely kin-based clans moving with their livestock, seeds, and sacred objects, their progress measured in generations. The environment they entered presented both sanctuary and severe challenge. They moved from the more open, sun-baked Sudanese plains into the rolling, fertile highlands of north-western Uganda. This demanded a profound adaptation of their knowledge. New forests needed to be understood, new soils tested for crops like millet and sorghum, and new ecological balances negotiated. Furthermore, they were not entering vacant territory. The region was home to other groups, and the Lugbara’s settlement involved both conflict and coexistence. Their pre-colonial society became characterised by fiercely independent, often rivalrous clan-based settlements, a political fragmentation that reflected their history as separate migratory streams yet also honed their skills in defence and territorial integrity.

The environment they entered presented both sanctuary and severe challenge. They moved from the more open, sun-baked Sudanese plains into the rolling, fertile highlands of north-western Uganda. This demanded a profound adaptation of their knowledge. New forests needed to be understood, new soils tested for crops like millet and sorghum, and new ecological balances negotiated. Furthermore, they were not entering vacant territory. The region was home to other groups, and the Lugbara’s settlement involved both conflict and coexistence. Their pre-colonial society became characterised by fiercely independent, often rivalrous clan-based settlements, a political fragmentation that reflected their history as separate migratory streams yet also honed their skills in defence and territorial integrity.This period of settlement and consolidation was where resilience transitioned into innovation. They ceased to be purely migrants and became adaptors. Their Sudanic cultural core—their language, their belief in a supreme creator (Adroa), and their ancestral veneration—fused with the practical realities of their new environment. The sacred hills and distinctive, large-termite mounds of their new homeland were incorporated into their spiritual geography, becoming sites for shrines and rituals. Their social structures, centred on the clan (’di), became the mechanism for organising land rights and community labour, ensuring survival and cohesion in their secured territories.

Thus, the “Historical Crucible” of migration did more than simply move a people; it fundamentally shaped the Lugbara character. It ingrained a pragmatic resilience, a deep connection to the land they had won through struggle, and a social model that valued both clan autonomy and collective defence. Their origin story, faithfully passed down through the recitation of the Adi (tribal history) by elders, is not a tale of a lost paradise but a foundational epic of endurance. It reminds every Lugbara that their community was built by those who endured the journey, adapted to the unknown, and possessed the strength to lay down roots. Their history, therefore, is the ultimate source of their tenacity—a living memory that they are, and have always been, survivors.

Thus, the “Historical Crucible” of migration did more than simply move a people; it fundamentally shaped the Lugbara character. It ingrained a pragmatic resilience, a deep connection to the land they had won through struggle, and a social model that valued both clan autonomy and collective defence. Their origin story, faithfully passed down through the recitation of the Adi (tribal history) by elders, is not a tale of a lost paradise but a foundational epic of endurance. It reminds every Lugbara that their community was built by those who endured the journey, adapted to the unknown, and possessed the strength to lay down roots. Their history, therefore, is the ultimate source of their tenacity—a living memory that they are, and have always been, survivors.A Sudanic Heritage: The Unbroken Thread of Kinship

To comprehend the Lugbara’s place in the world, one must listen not only to their stories but to the very fabric of their speech. Their language is more than a tool for daily commerce; it is the living archive of their ancestry, a profound testament to the adage that “blood is thicker than water.” This philological “bloodline”—their Sudanic heritage—anchors them within the vast Moru-Madi cluster, creating an invisible but unbreakable bond of kinship that stretches across national borders, connecting them to a broader cultural and historical arc throughout Central Africa.

Linguistically, the Lugbara tongue is classified within the Central Sudanic family, specifically under the Moru-Madi subgroup. This is not a dry academic label, but a key that unlocks their deepest past. It tells us that the Lugbara share a common proto-language with peoples like the Moru of South Sudan, the Madi of Uganda, and the Logo of the Democratic Republic of Congo. This relationship is one of cousinship, not mere coincidence. The core vocabulary—words for fundamental concepts like father (‘ba), mother (‘da), fire, water, and the sky—reveals shared roots. This mutual intelligibility, especially with nearest neighbours, means that a Lugbara elder from Arua could, with some effort, converse with a Moru elder from Morobo, uncovering in their dialogue echoes of a shared mother tongue spoken centuries before colonial maps divided them.

This linguistic kinship is the thread that traces back through their migratory history. It confirms the oral traditions of a north-westerly origin and that parting of ways at “Kolo.” As the ancestral group fragmented, their language diverged like branches from a single tree, evolving into distinct but related dialects. The Lugbara language, therefore, carries within its grammar and lexicon the fossilised imprints of that ancient journey. Place names, ritual terminology, and ancestral praise-names often hold clues understood across the Moru-Madi spectrum, forming a cryptic, shared code of heritage.

Beyond mere vocabulary, this Sudanic linguistic heritage implies a shared cultural substrate. It suggests common foundations in worldview that predate their separation. The most striking example is the concept of the supreme being, Adroa or Adronga. This dual-natured spirit—both singular creator and plural ancestral force—finds resonant echoes in the spiritual frameworks of their Sudanic cousins. The structural similarity in how they relate to the divine, the ancestral world, and the moral order points to a common philosophical cradle. Their languages provide the framework for similar modes of thought, from proverbial wisdom to the logical structures used in mediation and storytelling.

In the contemporary setting, this heritage is a double-edged heirloom. It is a source of immense pride and a marker of unique identity within Uganda’s rich ethnic tapestry, distinguishing them from neighbouring Nilotic or Bantu groups. Yet, it also underscores a political and social reality: the Lugbara are part of a transnational community. Their cultural and familial ties literally span the borders of Uganda, South Sudan, and the DRC. This can compound challenges, as conflicts or crises in one part of this linguistic arc reverberate through kinsmen in another.

In the contemporary setting, this heritage is a double-edged heirloom. It is a source of immense pride and a marker of unique identity within Uganda’s rich ethnic tapestry, distinguishing them from neighbouring Nilotic or Bantu groups. Yet, it also underscores a political and social reality: the Lugbara are part of a transnational community. Their cultural and familial ties literally span the borders of Uganda, South Sudan, and the DRC. This can compound challenges, as conflicts or crises in one part of this linguistic arc reverberate through kinsmen in another.Ultimately, the Sudanic heritage is the Lugbara’s silent, enduring inheritance. It is proof that while empires rose and fell and maps were redrawn, the more profound bonds of shared history, encoded in language, remained. It reinforces the truth that “blood is thicker than water”—the philological “blood” of a common tongue and ancestral origin forges a connection more resilient than the temporary separations imposed by geography or politics. In a globalising world that often threatens to homogenise, the Lugbara’s linguistic roots remind them—and us—that true identity is often held in the words we speak and the ancient kinships they silently affirm.

Rites of Passage as Identity Pillars: The Village that Makes the Person

For the Lugbara, the journey of an individual life is not a private affair but a public drama, where each act is marked, celebrated, and given meaning by the entire community. Their rites of passage—solemn and joyous ceremonies surrounding birth, puberty, marriage, and death—function as the essential pillars upholding both personal identity and social architecture. They embody the ancient adage that “it takes a village to raise a child,” extending its truth to encompass the entire lifespan: it takes a village to define a person, to unite them with another, and to reclaim them at life’s end. These rituals are the sacred machinery through which a biological event is transformed into a social fact, weaving the individual inextricably into the communal fabric.

Birth: Welcoming the Stranger into the Kinship Circle

The arrival of a child is met with rituals that immediately anchor the newborn in a network of relations extending beyond the living. A so-called “normal” birth integrates the child quietly into the family. However, births considered unusual, such as twins or a child born after the swift death of a sibling (an egugu), trigger profound ceremonies. The egugu is considered carrying the lingering spirit of the departed, requiring intervention to secure its place. An elder woman may plant a banana tree for the child and perform protective rites with a rattle, calling upon Adroa and the ancestors. This act, done on behalf of the community, signals that this vulnerable new life is already under collective guardianship. The child’s identity is thus framed from the outset not as an autonomous being, but as a precious link in a chain of lineage, requiring communal effort to protect.Puberty: The Silent Transition into Duty

While less ceremonially flamboyant than in some cultures, the transition to adulthood is deeply inscribed through expectation and instruction. There is no single moment, but a gradual assumption of responsibility guided by elders. Young men learn the arts of livelihood and the moral codes of conduct; young women master domestic sciences and the subtleties of social harmony. The “rite” here is the accrued weight of knowledge passed down, the shared understanding that to be Lugbara is to contribute to the whole. The individual’s emerging adult identity is forged precisely through learning their role in sustaining the village that raised them.

The individual’s emerging adult identity is forged precisely through learning their role in sustaining the village that raised them.Marriage: The Alliance that Strengthens the Web

Marriage is the ultimate expression of communal rather than merely individual union. The vibrant, multi-day ceremonies involve elaborate processions, song, and symbolic acts that bind two families irreversibly. The famous ritual where a representative of the groom’s party is smeared with cow dung at the bride’s homestead is a act of humble acceptance and playful testing, witnessed and enjoyed by all. When the bride is carried aloft, gazing skyward, she is elevated by the hands of her new community. This rite transforms two individuals into a new social node, strengthening the kinship web. Their personal bond becomes a pillar of broader social stability, creating alliances, redistributing resources, and producing the next generation of Lugbara.Death: Returning the Ancestor to the Community

Death, the final passage, is meticulously managed to ensure the deceased transitions properly to the ancestral realm while the living are reconstituted as a community without them. Funeral rites are extensive, involving wailing, storytelling, and feasting. The recitation of the Adi (clan history) by elders is crucial; it situates the deceased’s life within the epic narrative of the people, granting them a posthumous identity as an ancestor. The physical community grieves together, and through this shared performance, the social body heals itself. The deceased does not vanish, but is relocated within the collective memory, becoming a spiritual guardian whose continued influence reinforces the very bonds that now mourn their absence.In a modern context where individualism reigns, the Lugbara’s rites stand as a powerful counter-narrative. They assert that identity is not self-created, but communally bestowed and affirmed at every critical juncture. The adage proves true: the “village”—the living, the dead, and the yet-unborn—is the author of the person. These pillars of passage ensure that, despite the pressures of change, every Lugbara knows precisely who they are by understanding whose they are: a child of their parents, a member of their clan, and a steward of a legacy held in trust by the entire community.

The Mystical in the Mundane: The Unseen Compass

For the Lugbara, the tangible world of huts, fields, and livestock is merely the most visible layer of a far more complex reality. Their existence is guided by a profound and omnipresent spiritual ecology, where the mystical is not reserved for sacred groves or grand ceremonies but is the very medium of daily life. This worldview is governed by the principle that “the wheel turns, but the axle remains unseen.” While the daily grind of planting, arguing, trading, and celebrating forms the visible wheel of life, it rotates around the fixed, unseen axle of the spirit world, most significantly the supreme entity known as Adroa (or Adronga). This Great Spirit, and the host of ancestral spirits (ori), are not distant deities but intimate participants, providing the guiding force and ethical framework for every conceivable action.

Adroa: The Dual-Natured Architect of Reality

Adroa is a concept of profound complexity. It is understood as both the singular, transcendent creator of all things and, in another sense, the plural totality of all spiritual forces. This duality allows the Lugbara to perceive the divine as both the ultimate source and an imminent presence. Adroa is the author of the moral order, the final arbiter of justice, and the silent witness to every thought and deed. One does not casually call upon Adroa; its name is invoked in moments of ultimate oath, profound thanksgiving, or dire need. The spirit’s presence is felt in the inexplicable—both in bountiful harvests and in sudden misfortunes, which are scrutinised for messages about communal harmony or individual transgression.

Guidance in the Grain: Spiritual Counsel for Earthly Decisions

This belief system transforms everyday decisions into spiritual consultations. Before a significant undertaking—be it clearing a new field, embarking on a journey, or proposing marriage—the wise Lugbara seeks to discern the will of the unseen. This is where divination practices like Büro or Qbagga become essential tools of daily governance. By reading the fall of pebbles, the behaviour of a sacrificed chicken, or the patterns in a pot of water, the diviner (ajakasi) interprets messages from the ancestral spirits, who act as intermediaries to Adroa. A proposed course of action is thus not merely judged by its practical merits, but by its spiritual alignment. To proceed against an unfavourable reading is to invite misfortune, a risk no prudent person would take.Ethics Enforced by the Unseen: The Foundation of Conduct

The omnipresence of the spiritual directly moulds ethical conduct. The Lugbara moral code—centred on courage, loyalty, respect for elders, and communal responsibility—is not merely social etiquette but divine law. Wrongdoing is not just a crime against a person; it is an offence against the ancestors and a disruption of the cosmic balance maintained by Adroa. A lie, a theft, or an act of cowardice creates a spiritual pollution (edzoa) that can afflict not only the perpetrator but their entire family. Conversely, honourable conduct earns the favour and protection of the ancestral spirits. This framework provides a powerful internal and communal policing mechanism; one is never truly alone, for the spirits are perpetual witnesses. The adage proves true: the “unseen axle” of spiritual consequence ensures the wheel of society turns on a path of accepted morality.

From Naming to Harvest: Rituals Weaving the Spiritual into the Fabric of Life

This integration is visible in key rituals:Naming a Child: A name is often chosen following consultation with ancestors, linking the child’s identity to a forebear and placing them under specific spiritual patronage.

Settling Disputes: Elders may call upon the ancestors to witness a settlement. An oath sworn on Adroa is considered unbreakable, as the spiritual repercussions for falsehood are dire.

Agricultural Cycles: The otuke stones used in rain-making are not mere tools but vessels of spiritual power, cared for with reverence. A harvest is not just the result of labour but a gift from Adroa and the ancestors, acknowledged through first-fruit offerings at the ancestral shrine (ajo).

In a modern world often characterised by secular pragmatism, the Lugbara’s lived spirituality offers a starkly different paradigm. It asserts that there is no clear divide between the practical and the mystical. Every choice has a spiritual dimension, every success a divine favour, and every tragedy a potential spiritual lesson. The enduring power of this worldview lies in its ability to provide a coherent, unifying explanation for fortune and suffering, and an immutable compass for behaviour. It reminds us that for the Lugbara, life is a constant, respectful dialogue with the unseen—the very axle upon which their world turns.

Rain-Making: Where Faith Meets Ecology – Reading the Book of Nature

In the Lugbara heartlands of north-western Uganda, where life follows the sun’s relentless arc and the soil’s thirst dictates survival, the arrival of rain is the difference between abundance and despair. Here, the practice of rain-making transcends mere ritual; it represents a profound synthesis of spiritual faith and acute ecological stewardship. It is a discipline that embodies the adage “to read the book of nature,” where the environment is not a random set of phenomena but a legible text of signs and balances. The revered opi-ozogo dri (master of the rain) and the sacred otuke stones are the instruments through which this reading occurs, blending devotional practice with generations of observed environmental intelligence into a sophisticated system of communal resilience.

The Opi-Ozogo Dri: Interpreter and Intercessor

The rain-maker is not a sorcerer but a custodian of equilibrium. His title denotes a sacred office, often inherited, combining the roles of priest, meteorologist, and community psychologist. His authority stems from a perceived lineage-based connection to the ancestral spirits and Adroa, who govern natural forces. When drought threatens, the community’s anxiety is channelled to his doorstep. His subsequent actions are a structured performance of eco-spiritual diplomacy. He operates from specific, often elevated, sites—frequently near ancient, gnarled trees or distinctive termite mounds considered portals to the spiritual realm. Before any ritual, his first duty is observation: scanning the horizon for cloud formations, feeling the humidity in the wind, noting the behaviour of birds and insects. This is the “reading” of nature’s book. His rituals—involving prayers, chants, and offerings of grain or beer—are then precisely calibrated appeals to restore a broken balance. They give tangible form to the community’s hope and collective will, transforming passive anxiety into active, shared participation. His power lies as much in his ability to interpret environmental cues as in his spiritual intercession.

He operates from specific, often elevated, sites—frequently near ancient, gnarled trees or distinctive termite mounds considered portals to the spiritual realm. Before any ritual, his first duty is observation: scanning the horizon for cloud formations, feeling the humidity in the wind, noting the behaviour of birds and insects. This is the “reading” of nature’s book. His rituals—involving prayers, chants, and offerings of grain or beer—are then precisely calibrated appeals to restore a broken balance. They give tangible form to the community’s hope and collective will, transforming passive anxiety into active, shared participation. His power lies as much in his ability to interpret environmental cues as in his spiritual intercession.The Otuke Stones: The Convergent Symbols

The otuke, small quartzite stones carefully curated and passed down through generations, are the tangible heart of the ritual. To view them solely as magical talismans is to miss their deeper significance. They are, in fact, potent symbols of the confluence between faith and ecology.Spiritual Vessels: They are believed to be inhabited by or connected to specific ancestral spirits associated with rain and fertility. They are the physical anchors for spiritual force.

Ecological Instruments: Their treatment reveals empirical insight. They are meticulously kept damp or in cool, dark places like granaries or pots near water sources during dry seasons. This practice demonstrates an intuitive understanding of condensation and humidity. The belief that dry otuke lose their power mirrors the observable reality that arid conditions persist without atmospheric moisture.

Social Regulators: The stones are community property held in trust. Their well-being is everyone’s concern. A missing otuke triggers a communal search and divination, reinforcing social cohesion and shared responsibility for the environment that sustains all.

The Synthesis: A Sustainable Worldview

The genius of Lugbara rain-making lies in this seamless synthesis. The ritual under the sacred tree does not ignore the material world; it engages with it on multiple levels. The prayers are offered as the rain-maker reads the signs of a potential weather shift. The keeping of the otuke moist is both a spiritual obligation and a practical mimicking of the desired climatic state. The system enforces a posture of respect and attentiveness towards the environment. It codifies the understanding that humanity is not nature’s master but a participant in a delicate, interconnected system where spiritual disharmony and ecological neglect yield the same result: parched fields.In an era of climate change, this practice is not an archaic relic but a poignant lesson in integrated perception. Where modern science provides data models, the Lugbara system provides a moral and relational model. It teaches that sustainability is not merely a technical challenge but a cultural one, requiring a society to “read the book of nature” with both observational acuity and respectful humility. The opi-ozogo dri and his otuke stones remind us that true environmental stewardship may begin with the recognition that the natural world is not a machine to be fixed, but a sacred, legible text in which we are but one character.

Marriage: A Celebration of Communal Unity – The Tapestry Woven by Many Hands

Among the Lugbara, a wedding is far more than the union of two individuals; it is the vibrant, noisy, and essential process of weaving a stronger social fabric. It embodies the adage that “a single thread does not make a tapestry.” A marriage creates a new pattern by interlacing the distinct threads of two clans, and this intricate work requires the active, joyous participation of the entire community. The celebrated processions, symbolic rites, and feasting are not merely entertainment; they are the necessary, public acts of weaving that transform a private affection into a public, durable alliance, uniting families and recalibrating the social landscape for generations.

The Procession: A Public Claim and a Joyful Challenge

The ceremony begins with a declaration in motion. The groom’s kin, adorned in their finest and beating drums, form a boisterous procession that snakes its way towards the bride’s homestead. This is no stealthy retrieval. Their songs, full of proverbial praise and playful boasts, announce their intent to the entire hillside. It is a public claim, but also a submission to communal scrutiny. Upon arrival, they meet not a quiet welcome, but a series of symbolic tests. The most iconic is the smearing of a chosen representative—often the groom’s father or uncle—with cow dung at the compound’s entrance. This act, met with laughter and ululation, is profoundly symbolic. It represents the groom’s family humbly accepting the less glamorous aspects of life and responsibility (the dirt), proving their resilience and commitment. The bride’s party, by enacting this ritual, asserts its worth and protects its daughter’s honour, all within a framework of accepted custom that transforms potential tension into celebratory play.Symbolic Acts: The Language of Interconnection

Every ritualised action encodes deeper truths about the new relationship. The lifting of the bride aloft as she gazes skyward is not just triumphal; it signifies her transition under the watchful eyes of Adroa and the ancestors, blessing the union from the spiritual realm. The playful “raiding” of the groom’s homestead by the bride’s female relatives, who dash to “destroy” or claim items, symbolises the bride’s integration into her new home—she and her kin now have a stake and a voice within it. The sharing of specially brewed sorghum beer (dofara), poured in libations to ancestors before being drunk by all, physically embodies the merging of lineages. The feast itself, funded by contributions from both families, is a tangible redistribution of wealth and a demonstration of the new network’s collective strength.The Role of Elders and Clans: Architects of the Alliance

Throughout, the elders are the master weavers. They negotiate the bridewealth (ayua), which is less a “price” and more a solemn exchange of symbolic goods—livestock, hoes, blankets—that cements the bond between patriarchs and compensates the bride’s clan for the loss of her labour and progeny. Their speeches interlace the history of both clans, recalling past alliances and good character, setting the marriage within a timeless narrative. They preside over the rituals, ensuring every symbolic thread is correctly placed. This very public involvement makes the marriage incredibly resilient; it is not a fragile pact between two people, but a covenant witnessed and guaranteed by hundreds.Reinforcing the Social Fabric

The ultimate purpose of this communal extravagance is solidarity. In a society where kinship is the primary safety net, a marriage strategically extends that network. It creates obligations of mutual aid between in-laws, opens new avenues for trade and support, and ensures the children born of the union will have claims to land and patronage across a wider group. The wedding’s very public nature makes divorce socially difficult and rare, as it would unravel a tapestry so many hands have worked to weave. Thus, a Lugbara wedding is a profound lesson in social ecology. It demonstrates that the strongest institutions are those built not in private, but in the public square, with song, symbolism, and shared substance. It proves that “a single thread does not make a tapestry.” The strength, beauty, and resilience of the union—and by extension, the community itself—lie in the multitude of threads drawn together, each kin group contributing its colour and strength to a pattern meant to endure, shelter, and define them all for generations to come.

Thus, a Lugbara wedding is a profound lesson in social ecology. It demonstrates that the strongest institutions are those built not in private, but in the public square, with song, symbolism, and shared substance. It proves that “a single thread does not make a tapestry.” The strength, beauty, and resilience of the union—and by extension, the community itself—lie in the multitude of threads drawn together, each kin group contributing its colour and strength to a pattern meant to endure, shelter, and define them all for generations to come.Warfare and Leadership: The Forge and the Anvil

Within the historical memory of the Lugbara, conflict was not a distant abstraction but a periodic and visceral reality. Yet, their understanding of warfare transcended mere brute force, embodying a complex philosophy of power, responsibility, and spiritual arbitration. This realm was governed by the adage that “the true test of a warrior is not in his strength to break, but in his wisdom to mend.” The figure who embodied this paradox was the Ombasa, the warrior-leader, a man whose authority was forged in the heat of conflict but whose legacy was determined in the careful, often sacred, work of reconciliation that followed.

The Nature of Conflict: Inter-Clan Skirmishes and External Threats

Historically, large-scale wars against distant empires were rare. More common were edio pi, inter-clan skirmishes, erupting from disputes over land, livestock, or marital grievances. These conflicts were brutal but often limited, governed by unwritten codes of retaliation. A killing demanded a life in return, but this cycle could be halted through negotiation and blood compensation. The greater challenge came from external forces: the slave raiders associated with distant empires, and later, the advancing columns of colonial powers like the Belgians (Tukutuku) and the British. These encounters demanded a different scale of response, forcing fragmented clans to consider a fragile, larger unity against a common foe.The Ombasa: The Leader Who Channels the Storm

In this context, the Ombasa was not a hereditary king but a proven leader elevated by consensus. His legitimacy stemmed from palpable courage, tactical cunning, and, crucially, perceived spiritual favour. He was the community’s spearhead, but also its shield. Before any engagement, his role was one of preparation and divination. He would consult the ancestors and Adroa through elders, seeking signs of favour. Ceremonial sacrifices of a white chicken or a ram were performed at the clan’s war shrine, often located beneath a specific, ancient tree. The behaviour of the sacrificed animal—the flow of its blood, the final twitch of its limbs—was read as an omen. This ritual was not superstition; it was the essential process of seeking communal justification and moral fortification, transforming a violent act into a sanctioned defence of the spiritual and physical order.The Ceremony of Arms and the Quest for Divine Favour

Weapons themselves were subject to ritual. Men would gather their spears, bows, and shields, placing them before the shrine. The Ombasa or a senior elder would then bless them, calling upon ancestral warriors for strength and accuracy. These acts served a critical psychological purpose: they bonded the fighting men together in a sacred covenant, replacing individual fear with collective purpose. The belief that Adroa favoured the just cause was paramount. To go into battle without this spiritual sanction was to invite certain disaster, for the gods would not protect the unjust. Thus, warfare was always framed as an act of restoration—of stolen cattle, violated boundaries, or avenged kin—to regain a balance that Adroa himself would recognise.The Deeper Test: From Warrior to Peacemaker

Here, the adage proves its profound truth. The Ombasa’s greater test came after the conflict. A leader who could only break was a curse; his true worth was measured in his ability to mend. Following a skirmish, even a victorious one, the Ombasa was expected to lead the delicate negotiations for peace. He would parley with his counterpart from the rival clan, oversee the complex exchanges of blood wealth (komu) to compensate for lives lost, and preside over the rituals of reconciliation. These often involved sharing a ritual meal or drink, symbolising the end of hostility and the restoration of a workable, if wary, coexistence. This transition from breaker to mender required a different kind of courage—diplomatic, patient, and wise—ensuring that violence served a conclusive end rather than sowing seeds for future strife.In reflecting on Lugbara warfare and leadership, we see a system that refused to separate the martial from the moral, or the political from the spiritual. The Ombasa stood at the confluence of all these streams. His leadership reminds us that raw power, unchecked by the wisdom to heal and unify, is ultimately destructive. True authority, as the Lugbara understood, was a solemn charge to wield force only when sanctified by communal need and ancestral will, and to always be prepared to lay down the spear and take up the tools of peace. For in the end, the true test of a warrior is not in his strength to break, but in his wisdom to mend.

Divination Practices (Büro and Qbagba): The Lamp in the Darkness

In the Lugbara world, where misfortune can strike as suddenly as a dry-season lightning bolt and the reasons for sickness or crop failure are often hidden, life is inherently fraught with uncertainty. To navigate this perpetual shadow, the Lugbara developed sophisticated intellectual and spiritual technologies: the divination practices of Büro and Qbagba. These are not mere superstitions but structured, ritualised systems for seeking ancestral guidance, functioning as diagnostic tools for the health of the individual, the family, and the community. They embody the universal adage that “it is better to light a lamp than to curse the darkness.” Faced with the bewildering darkness of the unknown, the Lugbara do not simply despair; they methodically light the lamp of divination to illuminate causes, assign meanings, and chart a path forward, revealing humanity’s timeless quest to replace anxiety with agency.

Büro: The Judicial Inquiry of the Spirit World

Büro operates as a form of spiritual inquest or courtroom. It is typically employed in response to a specific crisis—a persistent illness, a series of deaths in a family, theft, or infertility. The process is deliberate and communal. A diviner (ajakasi), skilled in interpreting the will of the ancestors, presides. Using a set of ritual objects—often specially selected pebbles, sticks, or cowrie shells—he poses precise questions to the unseen.The objects are cast, and their configurations are “read.” This reading is not random; it is based on a deeply learned symbolic language that connects patterns to possible causes: Has a forgotten ancestor been neglected? Has someone broken a taboo (edzoa)? Is there malicious intent from a living enemy or a wandering spirit? Büro seeks to identify the root cause, the “why” behind the suffering. Its conclusion directs the necessary remedy: a specific sacrifice at the ancestral shrine, a confession of wrongdoing, or a ritual cleansing. It transforms vague dread into a defined problem with a prescribed solution, restoring a sense of order and controllable truth.

Qbagba: The Prophetic Glimpse and the Test of Intent

Qbagba, while related, serves a slightly different function, often more predictive or verificatory. It might be used before a major undertaking—a long journey, a marriage proposal, or the clearing of new land—to ascertain its prospective success. One common method involves the use of a divided gourd or pot. Questions are posed, and substances like flour, seeds, or water are manipulated. The outcome—whether substances mix, remain separate, or overflow—provides a yes/no or favourable/unfavourable answer. Its power also lies in testing truth. In disputes where testimony conflicts, Qbagba can be invoked as a spiritual lie detector. The belief that the ancestors will guide the outcome to expose falsehood places immense psychological pressure on the guilty, often compelling confession before the ritual is complete. Thus, Qbagba serves as a societal stabiliser, a way to arbitrate truth without resorting to immediate violence, by appealing to a higher, unquestionable authority.

Its power also lies in testing truth. In disputes where testimony conflicts, Qbagba can be invoked as a spiritual lie detector. The belief that the ancestors will guide the outcome to expose falsehood places immense psychological pressure on the guilty, often compelling confession before the ritual is complete. Thus, Qbagba serves as a societal stabiliser, a way to arbitrate truth without resorting to immediate violence, by appealing to a higher, unquestionable authority.The Diviner: The Interpreter of the Lamp’s Flame

The efficacy of both systems rests on the diviner. He is the scholar of symbolism, the psychologist discerning human guilt, and the mediator with the ancestral realm. His knowledge is painstakingly acquired through apprenticeship. His authority derives not from personal power, but from his skilled ability to “read” the messages sent through the medium of the ritual. He gives voice to the ancestors, translating the ineffable into actionable counsel. In lighting the lamp, he is the one who ensures the community can see by its flame.The Quest for Certainty in a Capricious World

Ultimately, Büro and Qbagba address a fundamental human condition: the intolerance of chaos. The Lugbara, like all people, seek narrative and causality. Random tragedy is psychologically unbearable. These practices impose a narrative—a coherent story where effects have spiritual causes, and those causes can be addressed through specific rituals. They replace the terror of arbitrary fate with the manageable framework of transgression and restitution, neglect and propitiation.In this light, the adage holds profound truth. The darkness is the chaos of the unexplained. The lamp is the divination ritual, its flame the clarity of ancestral verdict. To “light a lamp” through Büro or Qbagba is an active, courageous refusal to succumb to fear. It is a declaration that even in a world governed by unseen forces, humanity can seek answers, negotiate with the unseen, and restore balance. The Lugbara’s divination practices, therefore, are far more than folklore; they are a profound philosophical response to life’s uncertainties, a timeless testament to the human spirit’s need to find reason, even when it must be sought in the realm of the spirits.

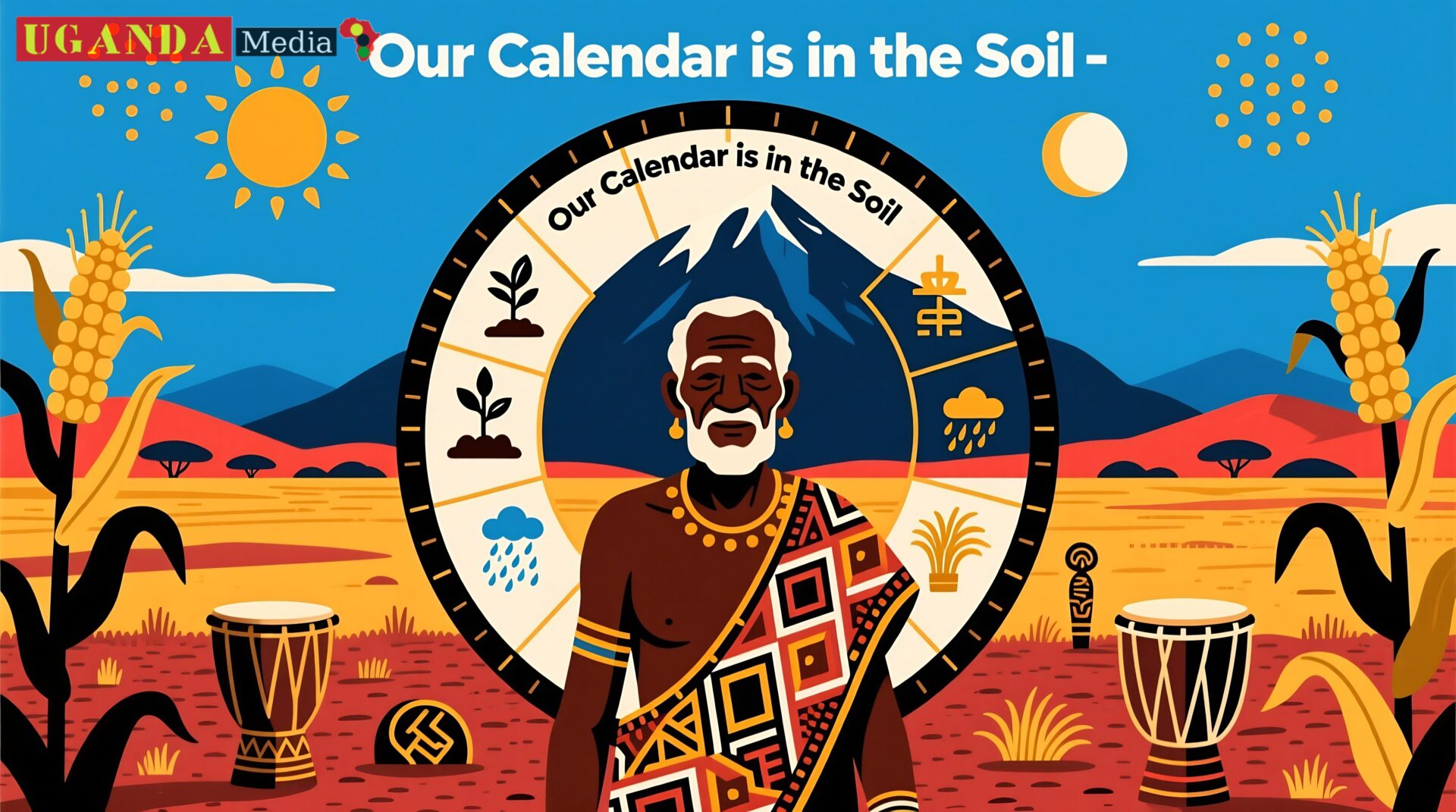

The Agricultural Symphony: The Rhythm to Which All Life Dances

For the Lugbara, agriculture is not an industry; it is a sacred, seasonal symphony performed in harmony with the land. Each stage, from the first breaking of the soil to the final storing of the grain, is interwoven with ritual, observation, and profound gratitude, embodying the fundamental adage that “you reap what you sow.” This phrase is understood in its fullest sense: the material harvest is directly tied to the spiritual and social seeds planted by the community. Their relationship with the earth is one of symbiotic reciprocity—a continuous dialogue of labour, respect, and propitiation that ensures the land yields its bounty and the community remembers its debt.

The First Movement: Prelude and Propitiation (Pre-Planting)

The symphony begins not with action, but with consultation. Before any hoe touches the earth, the signs are read. Elders observe the behaviour of insects, the flowering of specific trees, and the patterns of early rains. This empirical knowledge is then fused with spiritual counsel. The opi-ozogo dri (rain-maker) may be consulted to ensure his sacred otuke stones are properly tended, a ritual act that also serves as a communal meteorological preparation. Small offerings of last season’s grain might be made at the Ajo (ancestral shrine), informing the ancestors of the coming labour and seeking their blessing. This prelude establishes the correct spiritual and practical conditions, ensuring the community is in alignment with the natural order before a single seed is committed to the ground.

The Second Movement: Sowing as Sacred Act (Planting)

The act of sowing is itself ritualised. Planting is often commenced by senior women or the male head of the household, who perform a small, symbolic sowing in a purified plot. The seeds are sometimes mixed with ash or blessed herbs, a practice that combines spiritual protection with pragmatic pest deterrence. As the wider community joins in the work, the labour is structured along kinship lines, transforming a demanding task into a social event. The planting songs that may accompany this work are not merely to pass the time; they are incantations of hope, narratives of growth, and a rhythmic unification of human effort with the cyclical patterns of nature. Here, the adage “you reap what you sow” is enacted literally and metaphorically: the care, unity, and reverence invested in this stage are seen as critical determinants of the future harvest.The Third Movement: The Vigil of Nurturance (Growth)

The period of growth is a vigil, a time of watchful stewardship and continued dialogue. Rituals for protection are performed to guard the young crops from blight, pests, and malevolent spirits. The otuke stones remain a focal point, kept in cool, damp places to sympathetically encourage rain and humidity. This phase underscores the symbiotic relationship: the people nurture the crops, and in turn, the progressing growth nurtures the community’s hope and cohesion. Any threat to the fields is a threat to the collective future, demanding immediate communal and spiritual response.The Finale: Harvest as Gratitude and Redistribution (Harvest)

The harvest is the crescendo, a time of immense joy and profound thanksgiving. The first fruits are never casually consumed. They are the subject of the first-fruit rituals, where a portion of the harvest is ceremonially presented at the ancestral shrine. This is the essential act of closing the circle of reciprocity: acknowledging that the bounty is a gift from Adroa and the ancestors, facilitated by the land’s fertility. It is the tangible expression of reaping what was sown—not just agriculturally, but spiritually. Following this offering, the harvest becomes a social engine. The threshing and storing are communal activities, and the subsequent feast is a massive redistribution of wealth and celebration of shared effort. Granaries are filled, beer (dofara) is brewed from the new grain, and the entire community partakes in the fruits of their collective labour, reinforcing the bonds that made the harvest possible.The Coda: A Lesson in Sustainable Symbiosis

This agricultural symphony represents a holistic philosophy of sustainability. The land is not a passive resource but an active partner. The rituals are the protocols of that partnership, ensuring respect, attention, and gratitude are continually renewed. They encode practical ecological wisdom—crop rotation, soil preservation—within a framework of spiritual meaning, ensuring compliance not just through pragmatism but through sacred duty. In a world facing ecological crisis, the Lugbara’s agricultural practice offers a resonant lesson. It teaches that true abundance arises from a relationship of respect, not exploitation. Their calendar is a testament to the truth that to reap a plentiful and sustainable harvest, one must sow not only seeds but also reverence, communal effort, and a steadfast belief in the delicate, sacred balance between humanity and the earth that sustains it. The symphony continues, season after season, a timeless performance of survival and gratitude.

In a world facing ecological crisis, the Lugbara’s agricultural practice offers a resonant lesson. It teaches that true abundance arises from a relationship of respect, not exploitation. Their calendar is a testament to the truth that to reap a plentiful and sustainable harvest, one must sow not only seeds but also reverence, communal effort, and a steadfast belief in the delicate, sacred balance between humanity and the earth that sustains it. The symphony continues, season after season, a timeless performance of survival and gratitude.Ancestral Veneration: Standing on the Shoulders of Giants

For the Lugbara, the boundary between the living and the departed is not a wall but a permeable veil, and existence is a continuum where the ancestors remain active, vested participants in the life of the community. This profound connection, a cornerstone of their identity, is maintained through disciplined practice: the tending of shrines, the making of offerings, and the solemn recitation of oral histories. This entire system of veneration is governed by the adage that “we stand on the shoulders of giants.” The Lugbara understand that their present security, wisdom, and very identity are built upon the foundation laid by those who have gone before; to honour them is to ensure the stability and guidance necessary to face the future.

The Ajo: The Domestic Embassy to the Ancestral Realm

The focal point of this relationship is the Ajo, the ancestral shrine. This is not a grand public temple but an intimate, often simple structure within the family compound—a cluster of specially chosen stones, a post, or a dedicated corner of the main hut. The Ajo functions as a domestic embassy, a permanent portal for communication. It is here that the living ‘meet’ with the departed. The upkeep of the Ajo is a sacred duty, typically performed by the male head of the household (’ba) or a senior woman. Keeping it clean and in good order is a sign of respect, signalling to the ancestors that they are remembered and their space in the world of the living remains intact. Neglect is an unthinkable affront, believed to invite misfortune as the ancestors withdraw their protection.Offerings: The Currency of Relationship and Reciprocity

Communication at the Ajo is sustained through offerings, the essential currency of this ongoing relationship. These are not bribes but acts of reciprocity and sharing. Libations of the first local beer (dofara), portions of the harvest’s first fruits, or bits of choice food from a family meal are presented. The underlying principle is simple: as the ancestors are believed to influence fertility, health, and fortune, they are entitled to share in the bounty they help to provide. In times of crisis—illness, drought, or conflict—more formal sacrifices, such as a chicken or a goat, may be offered. This act is a potent petition, a tangible demonstration of need and respect that reaffirms the bond and seeks to restore a disrupted balance. Through these offerings, the abstract concept of ancestry becomes a daily, practical relationship of mutual obligation.The Adi: The Living Tapestry of Identity

The most profound act of veneration is the recitation of the Adi, the clan’s oral history. This is not casual storytelling but a formal, ritual performance, often delivered by an elder during ceremonies, disputes, or moments of collective decision-making. The Adi is the sacred narrative that charts the clan’s migrations, its heroic figures, its alliances, and its moral triumphs and failures. To recite the Adi is to invoke the ancestors directly, to make their journeys and judgements present in the moment. This recitation serves multiple vital functions. Firstly, it is an act of remembrance, ensuring the “giants” upon whose shoulders the living stand are not forgotten but are called by name. Secondly, it is a powerful tool for education and socialisation, embedding each new generation within a deep historical and moral framework. Thirdly, it provides precedent and guidance; contemporary dilemmas are measured against the ancestral wisdom enshrined in these stories. The Adi transforms history from a past event into a living force, continuously shaping identity, law, and behaviour.

This recitation serves multiple vital functions. Firstly, it is an act of remembrance, ensuring the “giants” upon whose shoulders the living stand are not forgotten but are called by name. Secondly, it is a powerful tool for education and socialisation, embedding each new generation within a deep historical and moral framework. Thirdly, it provides precedent and guidance; contemporary dilemmas are measured against the ancestral wisdom enshrined in these stories. The Adi transforms history from a past event into a living force, continuously shaping identity, law, and behaviour.A Symbiosis of the Living and the Dead

This system creates a powerful symbiosis. The living provide the ancestors with remembrance, honour, and sustenance through offerings. In return, the ancestors provide the living with a foundational identity, spiritual protection, and a timeless moral compass. They are the ultimate guardians of tradition and the enforcers of ethical conduct, as wrongdoing is seen as an offence against them.Thus, Lugbara ancestral veneration is far more than reverence for the dead; it is the active maintenance of a partnership across time. It confirms the adage: their present world is built upon the accumulated legacy, sacrifices, and wisdom of ancestral “giants.” By tending the shrines, making offerings, and recounting the Adi, the Lugbara do not dwell in the past. Instead, they engage in a continuous dialogue with it, drawing strength and direction to navigate the present, ensuring that the shoulders they stand upon remain strong enough to elevate generations yet to come.

Moral Codes Forged by Tradition: The Anvil of Community

Among the Lugbara, morality is not a vague ideal found in texts but a tangible, lived reality forged in the twin fires of ancestral teaching and communal practice. Values like courage, loyalty, and respect for elders are not merely encouraged; they are systematically instilled, becoming the invisible architecture of everyday life. This process embodies the old British adage that “manners maketh man.” For the Lugbara, it is tradition—the accumulated manners, rituals, and stories of the community—that literally constructs the moral person, shaping raw individuality into a respected member of the social fabric.

The Curriculum of the Ancestors: The Adi as Moral Blueprint

The primary textbook for Lugbara ethics is the Adi, the clan’s oral history. When elders recite the Adi during gatherings, disputes, or rites of passage, they are not simply telling tales. They are delivering a masterclass in applied morality. The narratives are populated with archetypal figures: the courageous Ombasa (warrior-leader) who defended the clan’s land, the loyal kinsman who shared his harvest during famine, the disrespectful youth who brought misfortune upon his family. Each story serves as a precedent, a case study that defines virtue and vice in Lugbara terms. Courage is thus learned not as an abstract concept, but as the embodied action of a specific ancestor in a specific battle. This teaching method ensures moral codes are inseparable from identity—to act virtuously is to act as a true Lugbara.

Apprenticeship in Daily Life: Practice as Pedagogy

Moral instruction extends far beyond storytelling into a constant, practical apprenticeship. Respect for elders is not learned by decree but through unbroken custom. A younger person relinquishes their seat, lowers their gaze, and offers the first taste of food or drink without being told. These are the “manners” that maketh the respectful person. Loyalty is instilled through the demands of the clan system. Participation in collective labour (emvu), contributing to a kinsman’s bridewealth, or standing in solidarity during a dispute are all practical exercises in loyalty. Failure to participate is not just laziness; it is a moral failing that brings social censure and spiritual risk, as it offends the principle of mutual obligation upheld by the ancestors.Ritual as Reinforcement: Ceremonies that Cement Character

Key rites of passage are the crucibles where these values are tested and publicly affirmed. The journey to marriage tests a family’s loyalty and respect through complex negotiations and symbolic acts of humility. The role of the Ombasa historically demonstrated that true courage must be tempered with wisdom and a commitment to peace. Even the treatment of the egugu child teaches communal responsibility and care for the vulnerable. Each ceremony is a live performance of the moral code, impressing its principles upon participants and observers through powerful experience rather than passive lecture.The Sanction of the Unseen: Morality Underpinned by the Spiritual

Critically, this moral framework is given ultimate sanction by the spiritual world. The ancestors (ori) and Adroa are the supreme arbiters of conduct. A cowardly act is not just a social disgrace; it dishonours the ancestral warriors. Disloyalty fractures the unity the ancestors died to preserve. Disrespect towards an elder is an affront to the wisdom they carry, wisdom that links directly to the forebears. Thus, moral failings carry consequences beyond social disapproval; they risk provoking ancestral wrath, manifesting as illness, drought, or misfortune. This spiritual dimension transforms ethics from social etiquette into a sacred covenant for maintaining cosmic and communal balance.The Enduring Forge

In a rapidly modernising Uganda, this traditional system faces challenges from individualistic ideologies and new religious doctrines. Yet, its core strength persists because it is holistic. It does not merely tell people what is right; it shows them, involves them, and embeds the lesson in stories, actions, and spiritual belief. It proves the adage: “manners maketh man.” The Lugbara individual is, in a very real sense, made by the manners—the time-honoured practices, rituals, and codes of respect—of their community. Their moral compass is not an internal needle swinging freely, but one calibrated for generations by the fixed stars of ancestral wisdom and communal expectation, ensuring that even in changing times, a Lugbara knows what it means to live well.The Challenge of Urbanisation: When the Village Square Grows Distant

The migration of Lugbara people from their rural homesteads to the bustling urban centres of Uganda—to Arua town, Kampala, or beyond—represents more than a simple change of address. It is a profound translocation from one universe of meaning to another, one that actively disrupts the delicate ecosystem of intergenerational knowledge and communal living. This process starkly illustrates the adage that “out of sight, out of mind.” The systems that for centuries instilled identity, morality, and skill rely on constant, shared proximity. When the physical landscape of the village is replaced by the anonymising city, the vital transmission lines of tradition fray, threatening to relegate a rich cultural heritage to the realm of distant memory.

The Fracturing of the Oral Classroom

In the village, education was holistic and ambient. The elder recounting the Adi (clan history) by the evening fire, the mother explaining the properties of a herb while tending the garden, the opi-ozogo dri demonstrating the care of the otuke stones—these were lessons woven into the fabric of daily life. Urban migration dismantles this classroom. In the city, life is regulated by the clock and the wage, not the seasons and communal rituals. Grandparents may remain in the village, while parents work long hours and children attend formal schools with a national curriculum. The sacred, informal moments for storytelling and observation evaporate. The specific knowledge of clan histories, ancestral burial grounds, and the nuances of ritual practice is not uploaded to the cloud; it resides in the minds of elders left behind. Without daily immersion, this knowledge becomes abstract, then forgotten. The ancestral voices grow faint, and the foundational Adi risks falling silent.

The specific knowledge of clan histories, ancestral burial grounds, and the nuances of ritual practice is not uploaded to the cloud; it resides in the minds of elders left behind. Without daily immersion, this knowledge becomes abstract, then forgotten. The ancestral voices grow faint, and the foundational Adi risks falling silent.The Dilution and Privatisation of Ritual

Communal rituals require a community in place. The rain-making ceremony holds little immediate relevance for a mechanic in a city garage. The intricate, multi-day wedding processions are logistically and financially impossible for migrants living in cramped urban rentals, leading to abbreviated, Westernised ceremonies. Crucially, these rituals lose their public nature. In the village, a rite of passage was a communal drama reinforcing shared values for all witnesses. In the urban context, these acts shrink into private family affairs, if they occur at all. Their power as tools for social cohesion and public moral instruction is drastically diminished. The symbiotic relationship with the land, enacted through agricultural rituals, is severed, leaving a spiritual disconnect from the cycles of nature.The Reshaping of Social Structures and Authority

The urban economy rewards individualism and nuclear family units, directly challenging the Lugbara’s clan-based ethos of collective responsibility. The authority of elders, so central to the moral code, attenuates over distance. Decision-making shifts from the kinship council to the individual or the immediate household. Concepts of loyalty are tested and often redirected towards new urban networks of colleagues, neighbours, or church groups, rather than the extended clan. The “out of sight, out of mind” reality means the subtle, everyday enforcement of social norms—the corrective glance, the word of praise from a respected elder—disappears, leaving a vacuum that may be filled by more anonymised, and sometimes conflicting, value systems.Spiritual Dislocation and Syncretism

The ancestral shrine (Ajo) is a fixed point in the homestead, a tangible portal to the departed. In the transient world of urban tenancy, such permanent, dedicated spiritual structures are rare. The practice of regular offerings and communication can lapse. While belief in Adroa and the ancestors often persists, its daily expression falters. This can lead to a turn towards more portable, organised religions like Christianity or Islam, or to a syncretic blending of faiths. Whilst this demonstrates adaptability, it also transforms the intimate, location-specific spiritual dialogue of Lugbara tradition into something more universalised and detached from their unique ecological and ancestral landscape.A Fragile Bridge, Not a Total Break

It is crucial to note that the link is not completely broken. Urban migrants often send remittances home, maintain strong ties, and return for major festivals or funerals, creating a fragile bridge between the two worlds. There is a growing consciousness of cultural loss, sparking efforts to document language and customs. Yet, the pervasive force of urban living remains. The challenge, therefore, is to navigate a modernity where the communal “village square” exists more in memory and occasional visits than as a daily reality. The Lugbara’s resilience is now tested in a new arena: to combat the “out of sight, out of mind” effect by finding innovative ways to translate the essence of their ancestral teachings—the courage, loyalty, respect, and spiritual connection—into forms that can survive and have meaning in the concrete labyrinths of the 21st-century city. The fear is not of change, but of amnesia; not of adaptation, but of the irreversible silence that falls when the chain of living transmission is finally broken.

The Lugbara’s resilience is now tested in a new arena: to combat the “out of sight, out of mind” effect by finding innovative ways to translate the essence of their ancestral teachings—the courage, loyalty, respect, and spiritual connection—into forms that can survive and have meaning in the concrete labyrinths of the 21st-century city. The fear is not of change, but of amnesia; not of adaptation, but of the irreversible silence that falls when the chain of living transmission is finally broken.The Double-Edged Sword of Globalisation: Gains on the Swings, Losses on the Roundabouts

For the Lugbara, globalisation is not an abstract economic theory but a daily reality of competing signals, a force that simultaneously empowers and erodes. It embodies the old adage of “what you gain on the swings, you lose on the roundabouts.” The undeniable benefits of connectivity and access are counterbalanced by pervasive homogenising pressures that threaten to smooth away the distinctive contours of Lugbara identity, creating a complex cultural bargain where every advance seems to demand a concession.

The Gains on the Swings: Connectivity, Voice, and Opportunity

One edge of the sword is sharp with promise. Digital connectivity has revolutionised communication within the far-flung Lugbara diaspora. Through mobile phones and social media, clans maintain contact across continents, mobilise resources for community projects back home, and share news with unprecedented speed. This creates a virtual, transnational village square, mitigating some effects of urban migration.Globalisation also provides tools for cultural preservation and advocacy. Lugbara musicians can record and distribute traditional music online; younger, educated Lugbaras use digital platforms to document elders’ stories or create content in the Lugbara language. Their distinct narrative can now be projected onto a global stage, challenging historical marginalisation. Furthermore, access to global education, healthcare, and markets offers tangible improvements in living standards and life choices, aspirations that are universally understandable and deeply desired.

The Losses on the Roundabouts: The Homogenising Tide

Yet, the return swing brings losses. The globalised cultural marketplace, dominated by Western—and increasingly, regional—media, exerts a powerful homogenising force. The aspirational imagery beamed into homes via television and the internet often champions individualism, consumerism, and modes of dress and behaviour alien to traditional Lugbara communalism. To many youths, deeply ingrained practices can begin to seem “backward” next to these glossy, modern alternatives. The “roundabout” here is the erosion of cultural self-confidence and the quiet devaluation of indigenous knowledge. This homogenisation commodifies culture, turning sacred symbols into souvenirs. Rituals risk being truncated or repackaged for tourist consumption or festival performances, divorcing them from their spiritual context and communal purpose. The sacred otuke stone becomes a curiosité, the rhythmic funeral dirge a stage performance. The profound, integrated meaning is hollowed out, leaving an aesthetic shell.

This homogenisation commodifies culture, turning sacred symbols into souvenirs. Rituals risk being truncated or repackaged for tourist consumption or festival performances, divorcing them from their spiritual context and communal purpose. The sacred otuke stone becomes a curiosité, the rhythmic funeral dirge a stage performance. The profound, integrated meaning is hollowed out, leaving an aesthetic shell.Most critically, globalisation accelerates language shift. English, and to a lesser extent Swahili or Luganda, become the languages of education, commerce, and upward mobility. The Lugbara language, the very vessel of the Adi and the nuanced concepts of Adroa and edzoa (taboo), retreats to domestic spaces and then, perilously, often not even there. As the language fades, so too does the unique worldview it contains, a loss far greater than vocabulary.

The Negotiation of Identity in a Global Stream

The Lugbara are not passive victims in this process. They are active negotiators, constantly making choices. A university student in Kampala may wear jeans and debate politics on Twitter, yet still scrupulously observe funeral rites and contribute to his clan’s bridewealth pool. A community might harness the internet to fundraise for a new well, using global tools to sustain the local village. This negotiation is the daily reality of modern identity.However, the pressure tilt is real. The economic and social rewards of assimilating into a globalised mainstream are powerful, whilst the reinforcement of tradition often relies on diminishing interpersonal transmission. The adage holds true: the gains on the swings—connectivity, education, healthcare—are concrete and life-enhancing. But the losses on the roundabouts—the dilution of language, the commodification of ritual, the subtle shift from communal to individual values—are insidious and cumulative, striking at the roots of cultural distinctiveness.

The ultimate challenge for the Lugbara is to harness the sword’s sharp edge—its connective and amplificatory power—to actively reinforce and revalue their heritage, whilst parrying its blunt, homogenising side. It is a struggle to ensure that global connectivity becomes a tool for cultural empowerment rather than a solvent for cultural uniqueness, proving that in the 21st century, the most profound act of resilience may be to navigate the global stream without drowning in it.

The ultimate challenge for the Lugbara is to harness the sword’s sharp edge—its connective and amplificatory power—to actively reinforce and revalue their heritage, whilst parrying its blunt, homogenising side. It is a struggle to ensure that global connectivity becomes a tool for cultural empowerment rather than a solvent for cultural uniqueness, proving that in the 21st century, the most profound act of resilience may be to navigate the global stream without drowning in it.Missionary Influences and Religious Syncretism: A Covenant Renegotiated

The arrival and establishment of Christian missionary activity within Lugbaraland represents one of the most profound and complex transformations in the tribe’s history. This encounter was not a simple replacement of one faith by another, but a protracted, often fraught, process of negotiation, rejection, and synthesis. It illustrates the enduring adage that “you can’t have your cake and eat it too.” For the Lugbara, engaging with Christianity offered powerful new spiritual and social capital, but it frequently demanded a costly down payment: the explicit renunciation of the ancestral covenant that had guided their world for centuries. The result is an ongoing, uneven landscape of religious syncretism—a blending of streams where old beliefs flow in new channels.

The Historical Impact: A Direct Challenge to the Cosmic Order

Early Catholic (Verona Fathers) and later Protestant missionaries arrived with a worldview that was fundamentally oppositional to Lugbara spirituality. They preached a monotheism that explicitly condemned the veneration of ancestors (ori) and the recognition of Adroa’s plural manifestations as idolatry. The Ajo (ancestral shrines) were labelled demonic, the otuke stones mere superstition, and the opi-ozogo dri (rain-maker) an agent of darkness. This was not merely a new theology; it was a direct assault on the pillars of Lugbara society: the link to the ancestors, the ecological pact with the land, and the moral authority of tradition.Conversion brought tangible benefits—access to Western education, healthcare, and a place within a powerful, global religious community. However, the cost was a spiritual and social rupture. Converts were urged to destroy shrines, abandon polygamous marriages, and cease participation in communal rituals. This created painful fissures within families and clans, pitting the “saved” against the “heathen” in a bitter struggle for the soul of the community. The initial impact was, in many ways, subtractive, demanding the relinquishment of core practices before any new identity could be fully formed.

The Rise of Syncretism: The Cake Re-imagined

Faced with this untenable either/or proposition, many Lugbara embarked on a pragmatic, often subconscious, process of syncretism. Unable and unwilling to completely discard the deep-seated worldview of their ancestors, they began to blend Christian frameworks with Lugbara cosmology. This is where the adage manifests: they sought, in essence, to have their cake and eat it too—to gain the benefits of the new faith while preserving the existential comforts of the old.This synthesis took many forms:

Theological Blending: Adroa, the Great Spirit, was seamlessly identified with the Christian God the Father. Jesus Christ and the saints often took on attributes of powerful ancestral spirits, acting as intermediaries. The Holy Spirit could be understood in terms of the pervasive, less personalised spiritual forces (adro) in the Lugbara world.

Ritual Adaptation: The ancestral shrine (Ajo) might be replaced by a 十 letter frame (cross) or a portrait of the Virgin Mary in the homestead, yet offerings of food or libations might still be placed before it, now reinterpreted as acts of thanksgiving to God rather than sustenance for ancestors. Prayers for rain might be directed to Jehovah, but the underlying belief that divine will controls meteorology remained intact.

Moral Re-alignment: Christian moral teachings on honesty, peace, and charity were often absorbed and mapped onto existing Lugbara virtues of loyalty, respect, and communal responsibility, giving them a new divine authority.

Ongoing Tensions and the Contemporary Landscape

This syncretism is not a stable endpoint but a field of ongoing tension. Pentecostal and evangelical movements, in particular, often wage a vigorous “second wave” against any residual “traditional” practices, condemning syncretism as backsliding. Conversely, many Lugbara Christians experience no contradiction in attending church on Sunday and consulting an elder about a family curse on Monday, viewing both as necessary tools for navigating a world still perceived as full of spiritual forces. The lasting impact is a fragmented spiritual geography. For some, Christianity has entirely replaced the old ways. For others, the two systems operate in parallel, addressing different needs. For a diminishing few, the traditional belief system remains largely intact, though often pushed to the margins. The community’s unified cosmic narrative has been irrevocably pluralised.

The lasting impact is a fragmented spiritual geography. For some, Christianity has entirely replaced the old ways. For others, the two systems operate in parallel, addressing different needs. For a diminishing few, the traditional belief system remains largely intact, though often pushed to the margins. The community’s unified cosmic narrative has been irrevocably pluralised.Thus, the missionary encounter forced a profound renegotiation of the Lugbara covenant with the unseen. While they could not fully “have their cake and eat it too” according to orthodox doctrine, their cultural resilience fashioned a new recipe—one where the ingredients of Pentecostal fervour, Catholic ritual, and ancestral memory are mixed in varying proportions from one household to the next. This syncretic faith is a testament to their adaptability, but it also underscores a permanent cultural displacement, a reminder that the price of new spiritual capital was a partial, and for some a painful, mortgage on the ancestral home.

Efforts in Preservation: The Stitch in Time

Confronted with the erosive forces of modernity, a growing and urgent movement has emerged within and beyond Lugbaraland, dedicated to the active preservation of a unique cultural heritage. This endeavour operates on the foundational adage that “a stitch in time saves nine.” Recognising that the loss of a language, a ritual, or an oral history is irrevocable, scholars, community elders, and cultural activists are working against the clock to document and revitalise these treasures before they fade from living memory. Their collective mission is to make the crucial, timely “stitches” today that will prevent the far greater labour of reconstructing a lost identity tomorrow.

The Academic Stitch: Documentation as Salvation

Pioneering this work were early ethnographers and linguists, most notably the Comboni missionary Father Ecidio Ramponi. His meticulous mid-20th century recordings of Lugbara language, folklore, and customs remain an invaluable archive, a baseline of knowledge captured before the full sweep of late-century change. Today, this academic effort continues with greater collaboration. Linguists from institutions like Makerere University are working with native speakers to create definitive dictionaries, grammars, and orthographies for the Lugbara language. This formal codification is not an act of fossilisation, but a vital tool for education and literary development, providing the scaffolding upon which the language can thrive in a modern context.Anthropologists and historians are engaged in sensitive ethnographic documentation. Using audio and video recording equipment, they are capturing elders performing rituals—from rain-making sequences to intricate funeral dirges—and, most critically, reciting the Adi, the clan histories. These recordings are stored in university archives and, increasingly, digitised for preservation. This work treats each elder as a living library, safeguarding the content of their knowledge for future generations, who may no longer have direct access to such human repositories.

The Community Stitch: Revitalisation from Within