The Digital Resistance: How Ugandan Writers Are Forging an Unbreakable Literary Future

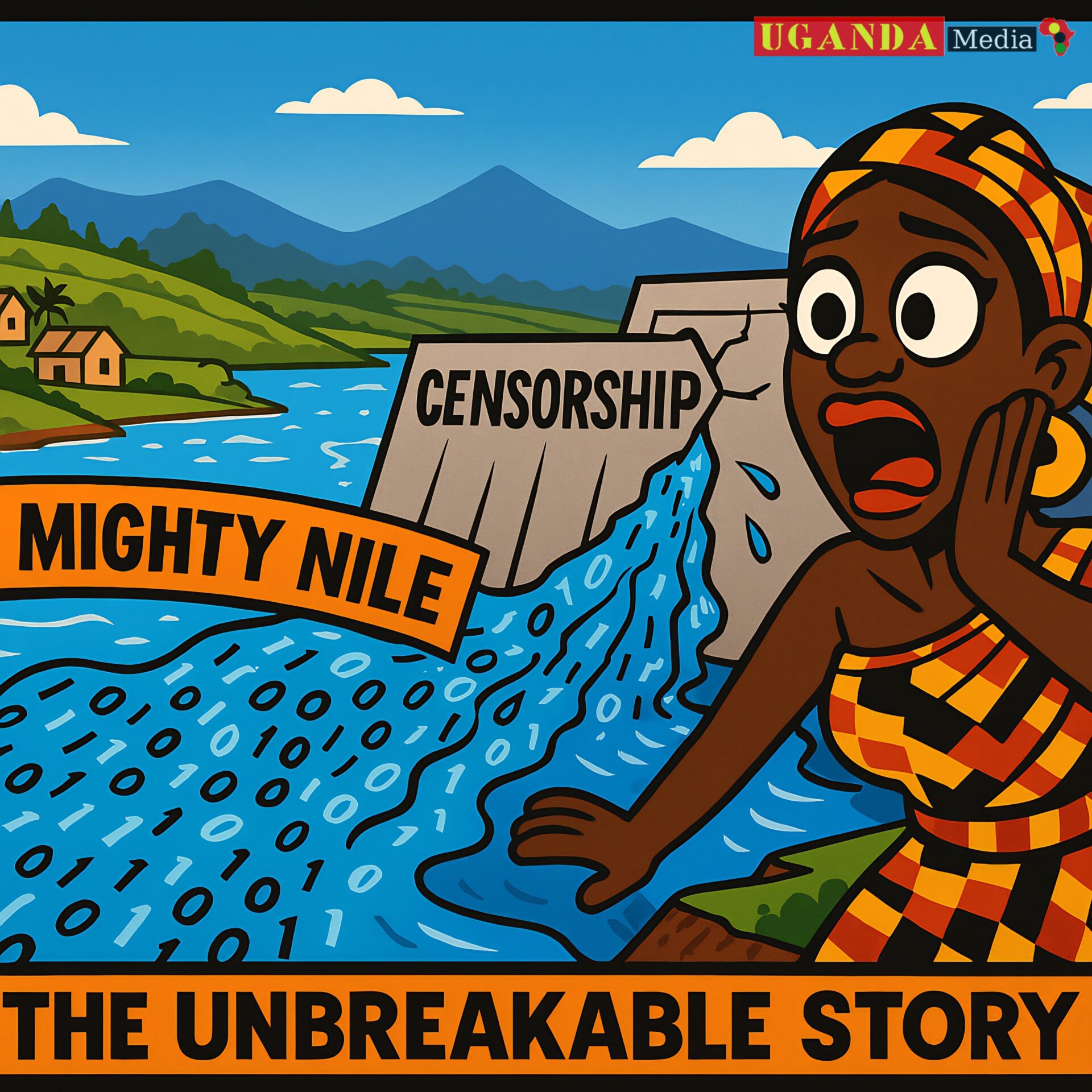

In an era where the pen is increasingly met with the sword, a profound revolution is unfolding within Ugandan literature. For the exiled writer, the critic, and the satirist, the digital age has transformed a landscape of isolation into one of immense possibility. This exploration delves into how Uganda’s storytellers are harnessing powerful digital tools—from the strategic ‘Cloudflare Gambit’ that protects their websites to the immutable promise of blockchain archives—to ensure their voices can never be silenced. We uncover the journey from physical exile to digital amplification, the battle against algorithmic tyranny on social media, and the creation of a sovereign digital presence. Beyond mere survival, this is about building a vibrant, Pan-African literary network, preserving oral traditions for the digital millennium, and pioneering new models of patronage that free art from politicised grants. This is the story of how Ugandan literature, as diverse and resilient as the nation itself, is being encoded into the very fabric of the internet—ensuring that the true narrative of its people, their struggles, and their beauty, flows unabated for the world to witness. Discover the tools, the strategies, and the unyielding spirit defining the new front line of free expression.

Kampala’s streets thrum with a rhythm that is uniquely its own—a symphony of taxi-hoots, market chatter, and the deep, resonant pulse of a drum from a village compound. This rhythm is the heartbeat of our stories. For generations, our tales were passed down under the vast, starry canopy of the African sky, woven into the fabric of our daily lives. But for the writer who dares to speak truth to power, that familiar rhythm can be abruptly silenced. Exile becomes a painful reality, a severance from the soil that nourishes our muse. Yet, from this displacement, a profound revolution is being born. The 21st-century digital era has not just given us a new notebook; it has given us a new nation—a borderless, digital realm where the Ugandan story, in all its rich and defiant glory, can never be erased.

Kampala’s streets thrum with a rhythm that is uniquely its own—a symphony of taxi-hoots, market chatter, and the deep, resonant pulse of a drum from a village compound. This rhythm is the heartbeat of our stories. For generations, our tales were passed down under the vast, starry canopy of the African sky, woven into the fabric of our daily lives. But for the writer who dares to speak truth to power, that familiar rhythm can be abruptly silenced. Exile becomes a painful reality, a severance from the soil that nourishes our muse. Yet, from this displacement, a profound revolution is being born. The 21st-century digital era has not just given us a new notebook; it has given us a new nation—a borderless, digital realm where the Ugandan story, in all its rich and defiant glory, can never be erased.

Here are twenty key points exploring this new frontier for Ugandan literature:

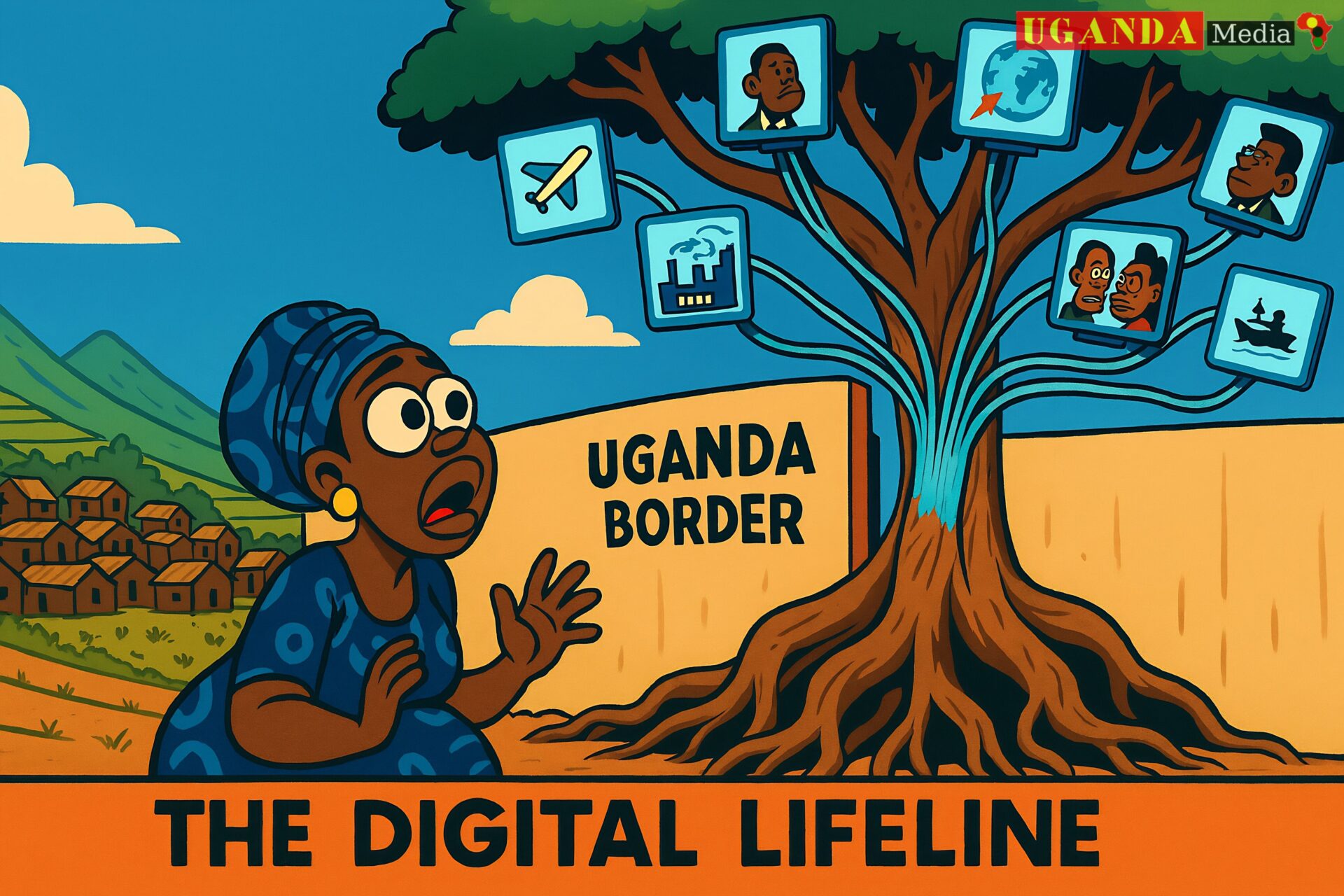

The Digital Lifeline: Weaving a New Bark Cloth from Threads of Exile

There is an old saying in Luganda: “Akatonoono k’eggwanga temmeweera.” (A small stream from the motherland should not be abandoned). For generations, this adage spoke to the duty of caring for one’s own, no matter how distant or diminished they may seem. For the writer forced to flee the shores of Lake Victoria or the lush hills of Kigezi, exile was that small, isolated stream—cut off from the great river of the national conversation. It was a cul-de-sac of the spirit, a place where one’s voice risked fading into the silence of distance and dislocation. The postman could be monitored, the pamphlets seized, the telephone tapped. The connection to the soil from which stories sprout was severed, and with it, a profound sense of purpose could wither.

The internet, however, has fundamentally rewritten this narrative. It has not merely provided a louder megaphone; it has transformed that lonely stream into a dynamic crossroads, a confluence of global currents where the exiled writer is no longer a forgotten tributary but a central channel in a vast, international flow of ideas.

The internet, however, has fundamentally rewritten this narrative. It has not merely provided a louder megaphone; it has transformed that lonely stream into a dynamic crossroads, a confluence of global currents where the exiled writer is no longer a forgotten tributary but a central channel in a vast, international flow of ideas.From Isolation to Integration

Where once a writer in a cramped flat in London or Nairobi would gaze longingly at outdated news from home, they are now virtually present in the bustling digital life of their homeland. They can monitor the price of matooke in Nakasero Market in real-time, feel the pulse of political discourse on Ugandan Twitter spaces, and witness the cultural debates unfolding in the comment sections of Kampala’s online newspapers. This is not passive observation; it is active re-integration. The writer is no longer speaking about a memory of Uganda, but into the living, breathing reality of its present. The digital space becomes a surrogate for the public square, the veranda where tales are told, and the university common room where ideologies clash.

The Global Community and the End of Artistic Starvation

Before this digital age, an exiled writer’s work often languished. It was dependent on the whims of foreign publishers, who might have a narrow, stereotypical view of “African literature.” Today, the world’s knowledge and audiences are at their fingertips. A writer can:

Publish Instantly: A poignant poem about the resilience of a boda boda rider can be shared on a personal blog and read from Gulu to Toronto within minutes.

Conduct Research: They can access academic journals, historical archives, and satellite imagery to ensure their depictions of a place like Fort Portal or Moroto are rich with authentic detail, despite their physical absence.

Find Their Tribe: They can connect with other dissident artists, translators, and independent publishers across the globe, forming solidarity networks that operate on principles of mutual aid and shared struggle, bypassing traditional, often exclusionary, literary gatekeepers.

This transforms the creative process from one of solitary confinement to one of collaborative potential. It ends the artistic starvation that exile once imposed.

A Tool of Collective Empowerment

This lifeline is not merely for individual salvation. It is a tool for weaving a new, collective bark cloth—a fabric of resistance and cultural preservation that is stronger than any single thread. The exiled writer becomes a node in a decentralised network of truth-telling. When one voice is silenced within Uganda’s borders, another, speaking from the diaspora using this digital lifeline, can amplify the message, ensuring the story continues. It creates a system of cultural backup, where the nation’s narrative is no longer held in a single, vulnerable location but is distributed and replicated across a global server that no single authority can seize or shut down.

In essence, the internet has allowed the exiled writer to honour the old adage in a profoundly new way. They have not abandoned the small stream; they have connected it to a mighty ocean. They ensure that the stories of the market woman, the fisherman on Lake Kyoga, and the teacher in a remote village school are not lost. They are documented, shared, and sanctified in the digital realm, preserving the soul of the nation from those who would seek to dictate a single, sanitised version of its truth. The crossroads is now their home, and from it, they build a future where no Ugandan voice is ever truly silenced again.

Uganda’s Literary Tapestry: The Unsilenced Chorus of the Hills

There is wisdom, as enduring as the Rwenzori mountains, which says: “A single bracelet does not jingle.” This simple adage speaks to the profound power of the collective, the symphony that arises from many voices coming together. It is the perfect metaphor for the literary heritage of Uganda—a vast, intricate, and resonant tapestry woven not from a single thread, but from a glorious multitude. Our nation’s stories are as diverse and breathtaking as our landscapes, and they form a national treasure that belongs not in a vault, but in the vibrant, dynamic public sphere, poised for its long-overdue global moment.

To speak of Ugandan literature is to speak of a living, breathing ecosystem. It is not a monolithic entity but a chorus of distinct, powerful voices, each rooted in its own specific soil:

To speak of Ugandan literature is to speak of a living, breathing ecosystem. It is not a monolithic entity but a chorus of distinct, powerful voices, each rooted in its own specific soil:The Epic Poems of the North: In the vast, open landscapes, under skies that seem to stretch into eternity, the tradition of the epic poem was born. These are not mere stories; they are chronicles of lineage, of courage, of migration and resilience. They are the historical memory of a people, recited in rhythms that mimic the steady beat of a communal heart, preserving philosophies of justice, community, and the intricate relationship between humanity and nature.

The Sharp Social Commentaries of the South: From the bustling, energetic centre of the nation, from the trading hubs and the cosmopolitan capital, emerges literature of sharp observation and satirical wit. This is the writing that holds a mirror to society, dissecting the follies of the powerful and the complexities of rapid urban life. It thrives on irony, exploring the tensions between tradition and modernity, wealth and poverty, the individual and the collective in a rapidly changing world. It is the critical conscience of the public sphere.

The Folktales of the West: In the shadows of mist-covered mountains and on the shores of great lakes, folktales flourish. Stories of cunning hares, wise elders, and mystical forces are not mere children’s fables; they are sophisticated vessels for social codes, ethical lessons, and subversive humour. They teach the virtue of the collective over the arrogant individual, and the power of the clever and the marginalised to outwit the brutish and the powerful.

The Lyrical Traditions of the East: From the slopes where tea plantations quilt the hillsides, come songs and lyrical narratives that speak of the land’s beauty and the burdens of labour. This is a poetry of the soil, intimately connected to the cycles of harvest, the flow of rivers, and the enduring spirit of those who work the earth, often exploring themes of displacement, belonging, and the quiet resistance found in cultural preservation.

This dazzling diversity is our greatest strength. It represents a complete human experience, offering not one story of Uganda, but a multitude of authentic, intersecting stories. This collective narrative is a national treasure, but it is a treasure that resides in the people’s domain—in the stories shared in a matatu, the proverbs cited by an elder, the poems scribbled in a notebook at a Kampala café, and the novels passed hand to hand.

Its power lies in its refusal to be simplified or homogenised. It challenges any singular, official narrative that seeks to present the nation as one-dimensional. By its very nature, this tapestry is a testament to bottom-up creativity, to the idea that a culture is built from the ground up by the people, not dictated from the top down. It is a deeply democratic and collective project.

And now, this chorus is waiting for its global moment. The world, often fed a narrow, simplistic view of Africa, is ripe for the complex, universal human truths embedded in our stories. The global literary scene has not yet fully heard the jingle of this particular, magnificent set of bracelets. Our moment awaits the platforms, the translations, and the recognition that this tapestry—woven from epic and satire, from folklore and lyric—is not just a regional artefact, but a vital, indispensable contribution to world literature. It is the unsilenced chorus of the hills, ready to sing to the world.

Exile as an Unlikely Amplifier: The Broken Pot That Waters a Wider Field

There is an old adage which reminds us that “the stone that the builder rejects becomes the cornerstone.” For generations, this was understood as a lesson in patience, in waiting for one’s own value to be recognised. But for the Ugandan writer who finds themselves forcibly removed from the soil of their birth, this proverb takes on a far more radical and immediate meaning. The state, acting as the short-sighted builder, believes that by casting out the critical voice, it has neutralised a threat, consigning it to the rubble of irrelevance. It could not be more mistaken. Forced removal is not the end of a writer’s career; it is the violent, unasked-for beginning of its most potent chapter, transforming a solitary voice into a resonant chorus that reaches international and diaspora audiences with a clarity once thought impossible.

From the Margins to the Centre of a Global Stage

Within Uganda’s borders, a critical writer can be deliberately marginalised. Their work can be excluded from state-controlled curricula, their book launches can be disrupted, and their name can be scrubbed from the pages of local press. They are contained. Exile shatters this container. Physically removed from the immediate sphere of state control, the writer is paradoxically thrust onto a vastly larger platform. They are no longer just a local dissident; they become an international witness.

This new position grants a unique and powerful authority. When they speak of the struggles of a fishing community on the shores of Lake Victoria being impacted by unchecked pollution, or of the quiet resilience of a women’s cooperative in the Karamoja region, they are no longer considered merely reporting local news. Framed by the context of their exile, these stories are instantly understood by global audiences as case studies in broader, universal struggles: the defence of the commons against private profit, the resilience of communal solidarity against top-down exploitation, and the fundamental human right to a dignified livelihood. The specific becomes universal, and the local grievance resonates on the world stage.

This new position grants a unique and powerful authority. When they speak of the struggles of a fishing community on the shores of Lake Victoria being impacted by unchecked pollution, or of the quiet resilience of a women’s cooperative in the Karamoja region, they are no longer considered merely reporting local news. Framed by the context of their exile, these stories are instantly understood by global audiences as case studies in broader, universal struggles: the defence of the commons against private profit, the resilience of communal solidarity against top-down exploitation, and the fundamental human right to a dignified livelihood. The specific becomes universal, and the local grievance resonates on the world stage.Speaking Truth to New Power Centres

From this new vantage point, the exiled writer can address levers of power that were previously unreachable. They can provide testimony to international human rights bodies, their work can be taken up by global solidarity movements, and they can collaborate with transnational publishers who are insulated from local political pressure. They can bear witness in a way that makes the powerful uncomfortable, not just in Kampala, but in the capitals of those nations whose economic and political support underpins the regime. The writer’s words become a form of accountability, a persistent, un-blurrable spotlight.

Furthermore, they find a profoundly important audience within the Ugandan diaspora. Scattered across continents, the diaspora often hungers for a connection to home that goes beyond the sanitised version promoted by official channels. The exiled writer provides this. They become a crucial node in a network of cultural and political memory, offering narratives that affirm the diaspora’s own experiences and suspicions. Their work educates a new generation born abroad about the complexities of their heritage, ensuring that the nation’s story is not lost or rewritten. In this, they perform a vital service: they help keep the collective consciousness alive, building a reservoir of truth that exists beyond the state’s reach.

In essence, the state’s act of rejection creates its own opposition. It misunderstands the nature of modern power and storytelling. It operates with an old logic, believing that to displace a person is to silence them. But in a connected world, to displace a writer is to amplify them. The stone it thought it had discarded becomes the very cornerstone of a new, borderless structure of resistance—a structure built on words, witnessed by the world, and dedicated to the unshakeable idea that a story, once liberated, can never be truly captive again. The broken pot, in the end, may yet water a wider and more fertile field.

The Continental Appetite for Story: Feeding the Hunger for Narrative

There is a patronising fiction that has been circulated in certain publishing houses and media circles, suggesting that the African reader possesses a diminished attention span, that their literary palate is suited only to the briefest of morsels. This claim—that our people “will not read beyond two paragraphs”—is not merely an insult; it is a profound and wilful misreading of the continent’s very soul. It is a myth crafted to justify a failure of imagination and a reluctance to invest in the depth of African intellectual life. The truth, evident from the bustling streets of Kampala to the remote trading centres of Kaabong, is the very opposite: there exists a voracious, unquenchable appetite for narrative, and the real challenge lies not in shortening our stories, but in meeting this hunger with quality, artistry, and a respect for the audience that captivates utterly.

To believe this myth is to ignore the evidence that surrounds us. It is to forget that the most enduring and complex narratives were born here, long before the printing press arrived on our shores. Consider the tradition of the evening fire. For generations, communities have gathered not for a two-paragraph summary, but for the slow, intricate unfolding of a tale. The story of the clever hare and the arrogant elephant is not a soundbite; it is a sophisticated narrative arc, rich with character development, social commentary, and suspense, holding children and adults alike in its thrall for hours. The epic poems of the Acholi, recounting the journeys of legendary figures like Labongo and Gipir, are not brief anecdotes; they are novel-length oral symphonies, demanding and receiving deep, sustained engagement. The appetite has always been there; it is a hunger for meaning, for connection, for seeing one’s own life reflected in a larger tapestry.

To believe this myth is to ignore the evidence that surrounds us. It is to forget that the most enduring and complex narratives were born here, long before the printing press arrived on our shores. Consider the tradition of the evening fire. For generations, communities have gathered not for a two-paragraph summary, but for the slow, intricate unfolding of a tale. The story of the clever hare and the arrogant elephant is not a soundbite; it is a sophisticated narrative arc, rich with character development, social commentary, and suspense, holding children and adults alike in its thrall for hours. The epic poems of the Acholi, recounting the journeys of legendary figures like Labongo and Gipir, are not brief anecdotes; they are novel-length oral symphonies, demanding and receiving deep, sustained engagement. The appetite has always been there; it is a hunger for meaning, for connection, for seeing one’s own life reflected in a larger tapestry.The contemporary manifestation of this is everywhere. The most popular radio dramas, those tales of family intrigue and social struggle that captivate the nation from the taxi park to the rural homestead, are serialised. Their power lies in their slow burn, in the audience’s investment in characters over weeks and months. The market for physical books, though often hampered by cost, is fiercely dedicated; a single, well-thumbed novel by a popular author will pass through dozens of hands, each reader devouring it from cover to cover. The problem has never been a lack of willingness to read. The barriers have always been structural: the prohibitive cost of books, the lack of accessible libraries, and the relentless daily struggle for subsistence that steals the leisure time required for deep reading.

The digital age has further exploded this myth. The readers who flock to online platforms, who consume long-form articles and serialised stories on their mobile phones, are testaments to this hunger. They are not skimming; they are engaging. They are diving into complex narratives about love, politics, corruption, and faith, stories that speak to their lived realities. The success of digital platforms publishing nuanced, lengthy investigative pieces or compelling serialised fiction proves that when content is relevant, resonant, and of high quality, the audience will not only read but will actively seek it out and share it.

This is where the writer’s charge lies. The challenge is not to dumb down or truncate our art to fit a fictitious, diminished reader. The challenge is to hone our craft with such skill, to tell stories with such compelling truth and beauty, that we command attention. We must write so clearly that the fisherman on Lake Kyoga forgets his nets for a moment, that the teacher in Mbarara stays up late under a dim bulb, that the market vendor in Kikuubo finds a reflection of her own struggles and triumphs in our prose. We must meet the profound hunger for narrative not with scraps, but with a feast. For a people weaned on the epic and raised on the serialised drama are not suffering from a short attention span; they are simply, and rightly, waiting for a story worthy of the wait.

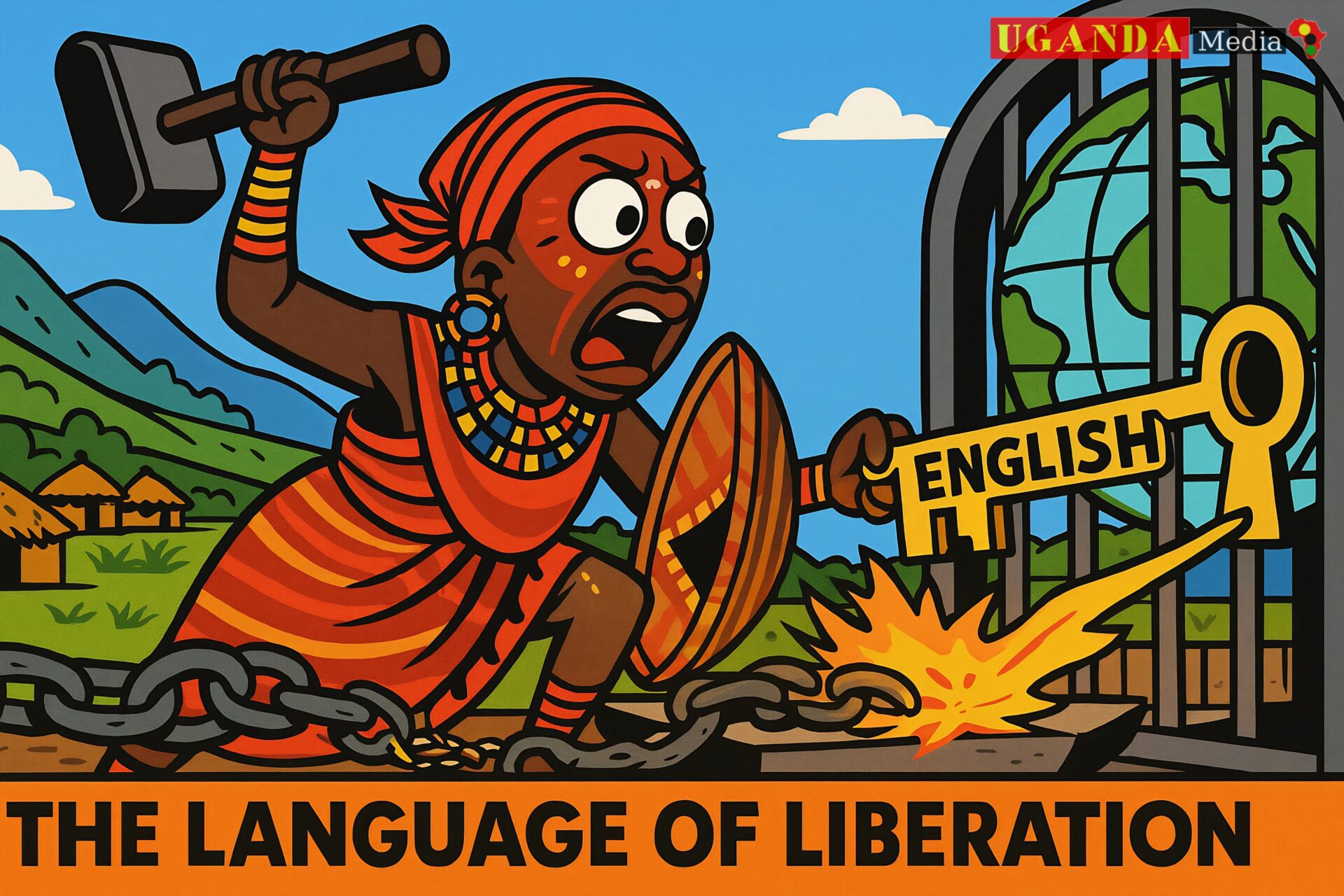

The Language of Liberation: Forging a Key from the Master’s Tool

There is a well-known saying that “a tool is only as good as the hand that wields it.” This simple truth cuts to the heart of a persistent and often disingenuous criticism levelled at exiled Ugandan writers: the accusation that we use “too much English.” This charge, frequently voiced by those who have themselves ascended through the very system built upon the English language—the university graduate, the comfortable professional—presents a false choice. It suggests that fidelity to one’s roots requires a rejection of the global stage. Nothing could be further from the truth. To write in English is not a betrayal of our mother tongues; it is a strategic, deliberate, and necessary act of liberation, a conscious wielding of a captured tool to dismantle the very structures it was designed to build.

The irony is palpable. The accusers, often beneficiaries of an education that prized and privileged English, now seek to pull the ladder up behind them. They have used this language as a key to personal advancement, to access economic opportunity and social status, yet they would deny the writer its use as a weapon for collective defence. This is a politics of containment, an attempt to ghettoise dissent by insisting it speaks only in a local dialect, ensuring its messages remain confined and easily dismissed by international power brokers. It is a demand that our grievances be whispered in the courtyard, never shouted from the global rooftop.

The irony is palpable. The accusers, often beneficiaries of an education that prized and privileged English, now seek to pull the ladder up behind them. They have used this language as a key to personal advancement, to access economic opportunity and social status, yet they would deny the writer its use as a weapon for collective defence. This is a politics of containment, an attempt to ghettoise dissent by insisting it speaks only in a local dialect, ensuring its messages remain confined and easily dismissed by international power brokers. It is a demand that our grievances be whispered in the courtyard, never shouted from the global rooftop.Our stance is different. We view language not as an innate identity to be policed, but as a practical instrument of communication and power. English, in the contemporary world, is the lingua franca of global discourse. It is the language of international law, of human rights reporting, of academic solidarity networks, and of transnational publishing. To tell the story of a land dispute in Amuru, or the struggle of a workers’ cooperative in Mbale, solely in a local language is to speak into a sealed room. To tell that same story in English is to broadcast it to a global audience that can exert pressure, offer solidarity, and bear witness. It is to ensure that the plight of the marginalised is not silenced by the borders of language.

This is not an abandonment of our linguistic heritage. The writer in exile carries the rhythm of Luganda, the proverbs of Runyankole, the metaphors of Lusoga deep within them. These languages inform the soul of our work, providing its unique cadence and cultural depth. The act of channelling this Ugandan soul through the English language creates a new, potent form of expression—one that can articulate the specific, nuanced reality of our people to those who need to hear it most. We are not erasing our mother tongues; we are building a bridge so that their essential truths can cross into a wider world.

The task, therefore, is not to lay down this tool, but to master it with even greater skill and subversive intent. We must wield English so deftly, so powerfully, and with such unassailable truth that it becomes an instrument of our own design. We use it to expose injustice, to organise solidarity, and to articulate a vision of a Uganda that belongs to all its people, not just a privileged few. The master’s tool, in the hands of the people, can indeed dismantle the master’s house. We are not using too much English; we are using just enough to ensure our story cannot be ignored.

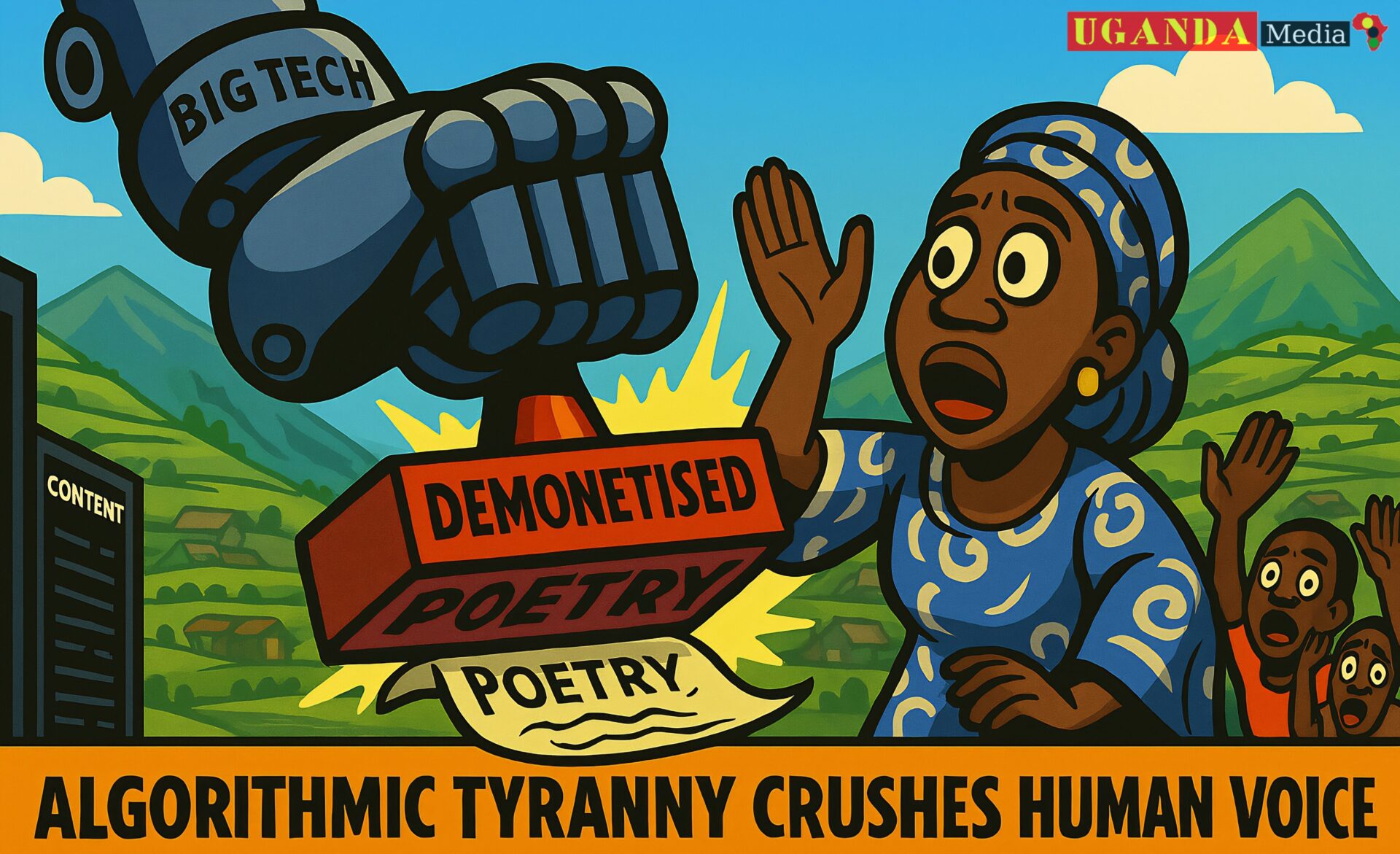

The Algorithmic Tyranny: The Ghost in the Machine of Modern Dissent

There is an old adage which warns us that “a wolf in sheep’s clothing is the most dangerous predator of all.” For the exiled writer, the digital landscape once promised a frontier of limitless freedom, a domain beyond the reach of the old gatekeepers. Yet, we have discovered that new, more insidious gatekeepers have emerged. Our new oppressor wears no uniform, carries no baton, and issues no direct orders. It is the unfeeling, opaque algorithm of big tech—a ghost in the machine that can silence critical voices as effectively, and often more completely, than any human censor. This is the algorithmic tyranny: a system of control that is decentralised, deniable, and devastatingly efficient.

Unlike the state censor, whose actions are often visible and can be contested, the algorithm operates in a shadowy realm of corporate secrecy. Its logic is a closely guarded secret, a proprietary formula designed not to uphold truth or justice, but to maximise engagement and advertising revenue. It favours the viral, the sensational, and the non-controversial. A nuanced, critical examination of power, a piece of literature that questions the fundamental structures of society, does not fit this profitable mould. Consequently, it is quietly suppressed. It is not deleted with a dramatic stamp of “BANNED”; it is simply made invisible. Its distribution is throttled, it is buried deep in search results, and it is denied the oxygen of visibility that is the lifeblood of the digital public square. This is a form of censorship by obscurity, where a writer can shout into a void they believe is a global town square.

This creates a profound and chilling paradox. We have built our digital homesteads to escape the direct control of the state, only to find ourselves tenants on land owned by a distant, unaccountable landlord whose terms of service can change on a whim. A post detailing the struggles of a community displaced by a large-scale agricultural project can be flagged as “controversial” or “spam.” A satirical poem about the concentration of wealth can be deemed to violate “community standards” by an automated system that understands neither satire nor the specific context of economic injustice in Uganda. The writer is left with no one to appeal to, no face to confront—only the cold, automated reply of a machine, enforcing a form of bland, commercial conformity that is inherently hostile to radical thought.

This creates a profound and chilling paradox. We have built our digital homesteads to escape the direct control of the state, only to find ourselves tenants on land owned by a distant, unaccountable landlord whose terms of service can change on a whim. A post detailing the struggles of a community displaced by a large-scale agricultural project can be flagged as “controversial” or “spam.” A satirical poem about the concentration of wealth can be deemed to violate “community standards” by an automated system that understands neither satire nor the specific context of economic injustice in Uganda. The writer is left with no one to appeal to, no face to confront—only the cold, automated reply of a machine, enforcing a form of bland, commercial conformity that is inherently hostile to radical thought.This tyranny is particularly potent because it is so difficult to organise against. How does one protest a mathematical formula? How does one demand transparency from a system whose power relies on its opacity? The state’s violence is direct and legible; the algorithm’s violence is structural and diffuse. It creates a system where dissent is not forcibly silenced but is instead engineered to fail, its reach systematically curtailed by a code that privileges the status quo.

Therefore, our struggle must evolve. Our defiance must now be directed not only against the visible hammer of the state but also against the invisible hand of the algorithm. This means continuing to build our own independent platforms, exploring decentralised technologies that are resistant to such control, and consciously building networks of distribution that operate on a human scale—through mailing lists, encrypted channels, and community-based sharing. We must outsmart the machine, using our collective wit to ensure that our stories, our analyses, and our truths continue to find their audience. For the wolf in the code may be a fearsome predator, but it cannot hunt what it cannot see, and it cannot silence a story that the people themselves have chosen to share.

The Rise of Social Media Arenas: The New Marketplace of Ideas

There is an old adage that “in the multitude of counsellors, there is safety.” For generations, this wisdom was rooted in the physical agora—the public gathering place where citizens could debate, dissent, and shape the conscience of the community. In today’s Uganda, where traditional public squares can be fraught with peril for those who speak uncomfortable truths, a new and vital marketplace of ideas has emerged. Platforms like Twitter, Facebook, and WhatsApp have become our digital agorae, not merely as tools for connection, but as essential, vibrant arenas where critical writers forge communities of dissent, solidarity, and unyielding discussion, creating a safety that resides precisely in their multitudes.

These platforms have shattered the state’s monopoly on public narrative. Where a single newspaper can be pressured and a radio station’s broadcast licence threatened, the digital arena is fluid and decentralised. A writer can share a potent allegory about the silencing of village elders, and within moments, it is being debated by academics in Makerere, shared by activists in Gulu, and analysed by the diaspora in London. This instantaneous, borderless exchange creates a tapestry of resistance that is incredibly difficult to suppress. It functions as a form of collective intelligence and mutual protection, where the act of sharing and discussing itself becomes a defence against oblivion and distortion.

These platforms have shattered the state’s monopoly on public narrative. Where a single newspaper can be pressured and a radio station’s broadcast licence threatened, the digital arena is fluid and decentralised. A writer can share a potent allegory about the silencing of village elders, and within moments, it is being debated by academics in Makerere, shared by activists in Gulu, and analysed by the diaspora in London. This instantaneous, borderless exchange creates a tapestry of resistance that is incredibly difficult to suppress. It functions as a form of collective intelligence and mutual protection, where the act of sharing and discussing itself becomes a defence against oblivion and distortion.Furthermore, these arenas have given rise to what can be understood as “organic communities of verification.” In the absence of a free and fair press, social media becomes the space where accounts are cross-referenced, witness testimonies are gathered, and official statements are held to account by the crowd. When a writer posts about the environmental impact of a new industrial project on the banks of the Nile, the discussion that follows is not passive. Fishermen from the area might comment with their own observations, lawyers might offer interpretations of the land rights involved, and teachers might share the piece with their students. This transforms the writer from a solitary voice in the wilderness into the catalyst for a living, breathing, and self-correcting public inquiry.

This represents a profound shift in power. It is a bottom-up reclamation of the public sphere. These digital agorae are not owned by the powerful; they are inhabited and shaped by the people. They allow for the rapid organisation of thought and the cultivation of a shared consciousness that transcends ethnic, religious, and regional divisions. The struggle is no longer just about occupying physical space; it is about dominating the discursive space—the space where ideas are formed, hearts are won, and the moral authority of power is either legitimised or eroded.

Of course, this marketplace is not without its perils—it can be a chaotic and contested space. But within that chaos lies its emancipatory potential. It prevents any single narrative, especially one imposed from above, from claiming absolute authority. In the multitude of voices, in the cacophony of debate and the solidarity of shared struggle, critical writers find their counsel, their audience, and their safety. They have built a new public square, not with bricks and mortar, but with data and determination, ensuring that the conversation about Uganda’s future remains alive, open, and defiantly free.

The Power of Digital Self-Sovereignty: Planting Your Flag on Unassailable Ground

There is a timeless piece of wisdom which states, “A man’s home is his castle.” For generations, this principle has represented the ultimate form of security and autonomy—the right to a truly one space’s own, governed by one’s own rules, a refuge from the overreach of external powers. For the exiled Ugandan writer, this concept has found a radical new expression in the digital realm. The most significant and transformative power shift in our time is not merely access to a platform, but the ability to own one. The creation of a personal website is the digital equivalent of building that castle; it is the establishment of a sovereign territory in cyberspace, a liberated zone where our voice is the only authority.

This act of digital self-sovereignty represents a fundamental break from the feudal dynamics of social media. On corporate platforms, we are merely tenants. We till the land, plant our ideas, and build our audience, but we do so on soil owned by a distant, profit-driven landlord. They can change the rules of tenancy without our consent, evict us with the flick of a switch, and harvest the fruits of our intellectual labour for their own gain. Our castle, in that context, is built on another’s land, subject to their whims and their secret algorithms.

This act of digital self-sovereignty represents a fundamental break from the feudal dynamics of social media. On corporate platforms, we are merely tenants. We till the land, plant our ideas, and build our audience, but we do so on soil owned by a distant, profit-driven landlord. They can change the rules of tenancy without our consent, evict us with the flick of a switch, and harvest the fruits of our intellectual labour for their own gain. Our castle, in that context, is built on another’s land, subject to their whims and their secret algorithms.A personal website, however, flips this power dynamic on its head. It is a declaration of independence. It is a plot of land on the internet that we own outright. The writer becomes the architect, the governor, and the sole curator of this space. Here, there is no intermediary to deem a story “too controversial” or an analysis “not suitable for advertising.” The complex, nuanced narrative about the resilience of a farmers’ cooperative in Mbale can be published in its entirety, without fear of demonetisation or shadow-banning. The archives of one’s work remain intact, a permanent and unalterable record of thought and testimony, immune from the digital memory hole of a corporate platform’s policy change.

This is not an act of isolation, but of fortified connection. From this secure base, the writer can engage with the world from a position of strength, not supplication. They can link out to other independent voices, creating a network of sovereign territories—a digital federation of free thought that operates on principles of mutual aid and solidarity, rather than corporate competition. It is a direct challenge to the centralisation of information, creating a resilient, distributed network of truth that cannot be silenced by targeting a single, central platform.

In a Ugandan context, where the struggle has so often been about the control of space—physical, political, and narrative—this is a revolutionary act. It is the digital corollary to a community reclaiming a parcel of land from a powerful absentee landlord. It is the establishment of a self-governed space where the story of our people can be told without concession, without dilution, and without fear. By planting our flag on our own digital plot, we secure not just a platform, but a permanent home for our conscience. We build a castle whose walls no censor can scale, ensuring that our stories become part of the unassailable landscape of truth.

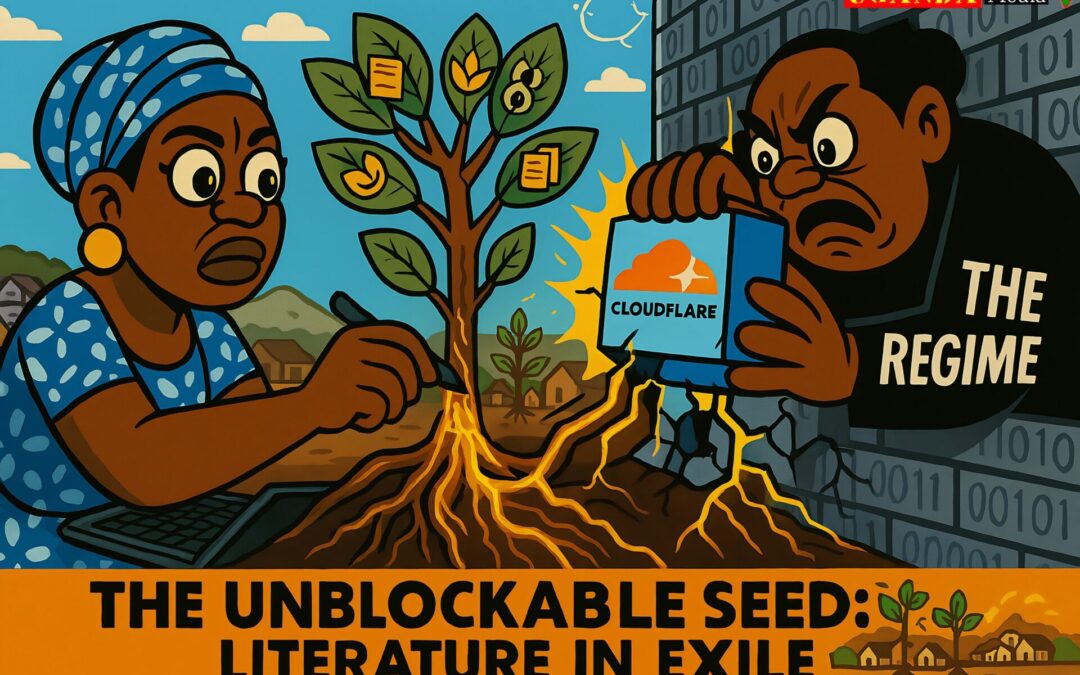

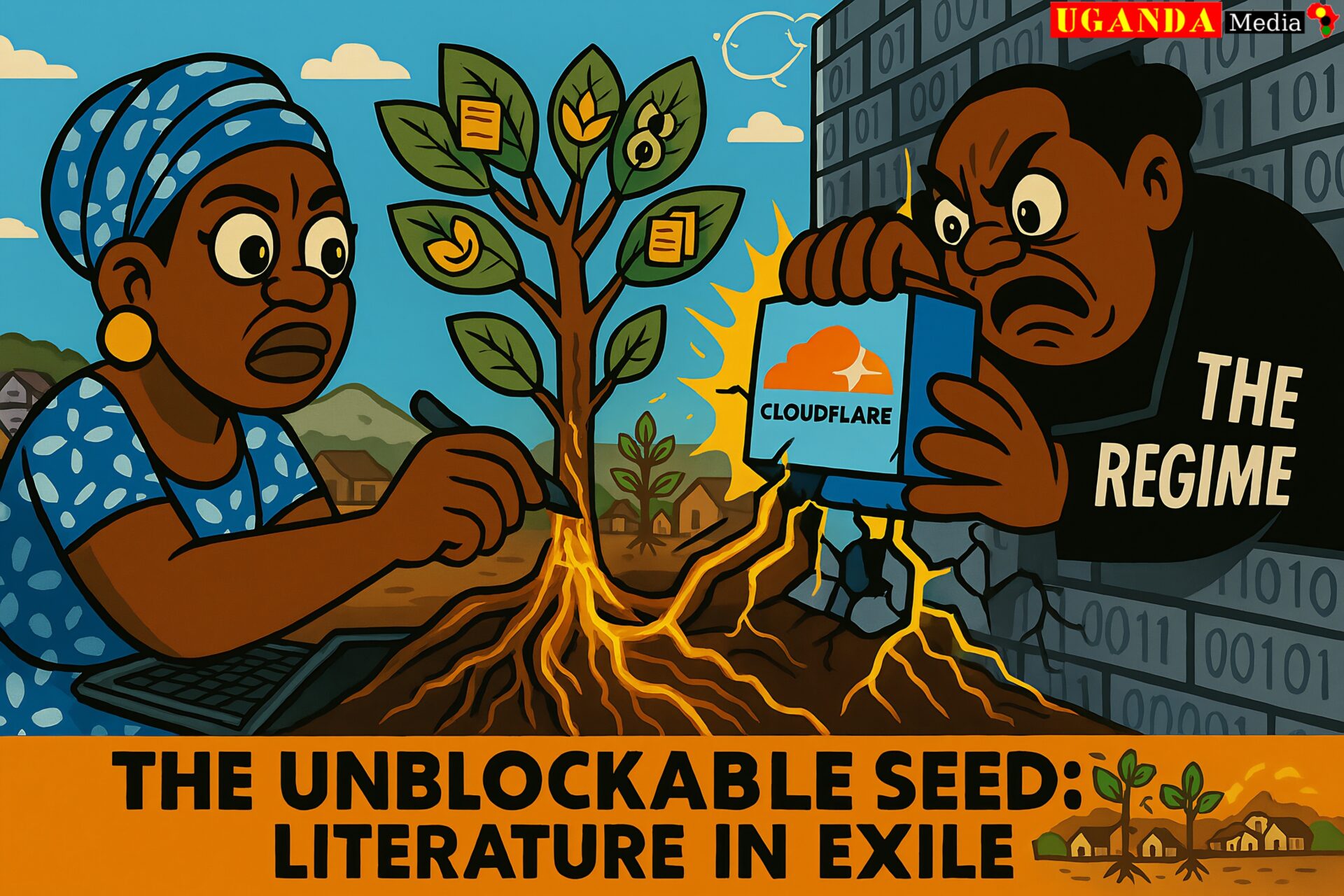

The Cloudflare Gambit: Turning the Giant’s Own Strength Against Him

There is a powerful adage that advises, “if you cannot move the mountain, you must find a path around it.” For the exiled writer, the mountain is the immense, obstructive power of the state, which can appear immovable. Direct confrontation is often futile. But the digital age offers a more cunning form of resistance—a form of intellectual jujitsu that uses the opponent’s own mass and momentum against them. This is the essence of the Cloudflare Gambit: a masterstroke of strategic hosting, where a writer places their website on the same global infrastructure that the state itself relies upon. In doing so, they create a paradoxical shield; for the state to block the writer’s voice, it must risk disabling its own digital capabilities.

To understand this, one must first appreciate the nature of modern state power. A government does not simply exist as a physical entity; it operates a vast, digital nervous system. Its ministries, its revenue authority, its security apparatus, and its public communications all depend on being reliably accessible online. To ensure this reliability and protect against attacks, many states, including Uganda’s, utilise the services of large content delivery networks (CDNs) like Cloudflare. These services act as a protective buffer, shielding government websites from crashes and cyber threats, ensuring they are always available to citizens and the world. The state, in essence, has built its digital house upon foundations poured by a third party.

To understand this, one must first appreciate the nature of modern state power. A government does not simply exist as a physical entity; it operates a vast, digital nervous system. Its ministries, its revenue authority, its security apparatus, and its public communications all depend on being reliably accessible online. To ensure this reliability and protect against attacks, many states, including Uganda’s, utilise the services of large content delivery networks (CDNs) like Cloudflare. These services act as a protective buffer, shielding government websites from crashes and cyber threats, ensuring they are always available to citizens and the world. The state, in essence, has built its digital house upon foundations poured by a third party.The exiled writer, in a act of brilliant subversion, builds their own small, critical hut on the very same foundation. By hosting their website on Cloudflare, they intertwine their digital existence with that of the state. They are, in a sense, hiding in the giant’s shadow. When the state’s censors identify the writer’s site as a threat and move to block it within Uganda’s borders, they face an impossible choice. The technology used to block a website is often a blunt instrument; it cannot always distinguish between a critical blog and a vital government portal if they are served from the same underlying network. To block the IP addresses associated with Cloudflare in order to silence one writer would be to block access to the very government services that legitimise the state and facilitate its operations.

This creates a powerful deterrent. It is the digital equivalent of a writer standing so close to the king that the royal guard cannot swing their sword without injuring the monarch. The regime is caught in a trap of its own making, forced to choose between tolerating a dissident voice or inflicting catastrophic self-harm upon its own digital infrastructure. Will it block a website that details the struggles of landless farmers in the Albertine region if it means that the official portal for business registration also goes offline, crippling economic activity? Will it silence a chronicle of political history if it means its own public health information systems become inaccessible?

This creates a powerful deterrent. It is the digital equivalent of a writer standing so close to the king that the royal guard cannot swing their sword without injuring the monarch. The regime is caught in a trap of its own making, forced to choose between tolerating a dissident voice or inflicting catastrophic self-harm upon its own digital infrastructure. Will it block a website that details the struggles of landless farmers in the Albertine region if it means that the official portal for business registration also goes offline, crippling economic activity? Will it silence a chronicle of political history if it means its own public health information systems become inaccessible?This is not a plea for mercy; it is a checkmate through strategic positioning. The Cloudflare Gambit demonstrates that in the networked world, power is not merely about force, but about interconnection and dependency. The writer, by understanding the architecture of the system better than the censor, finds a path around the mountain. They secure their voice not by building higher walls, but by weaving their thread so intricately into the state’s own tapestry that to pull it out would unravel the entire design. It is a profound affirmation that the cleverness of the collective, when applied with precision, can outmanoeuvre the brute strength of the powerful.

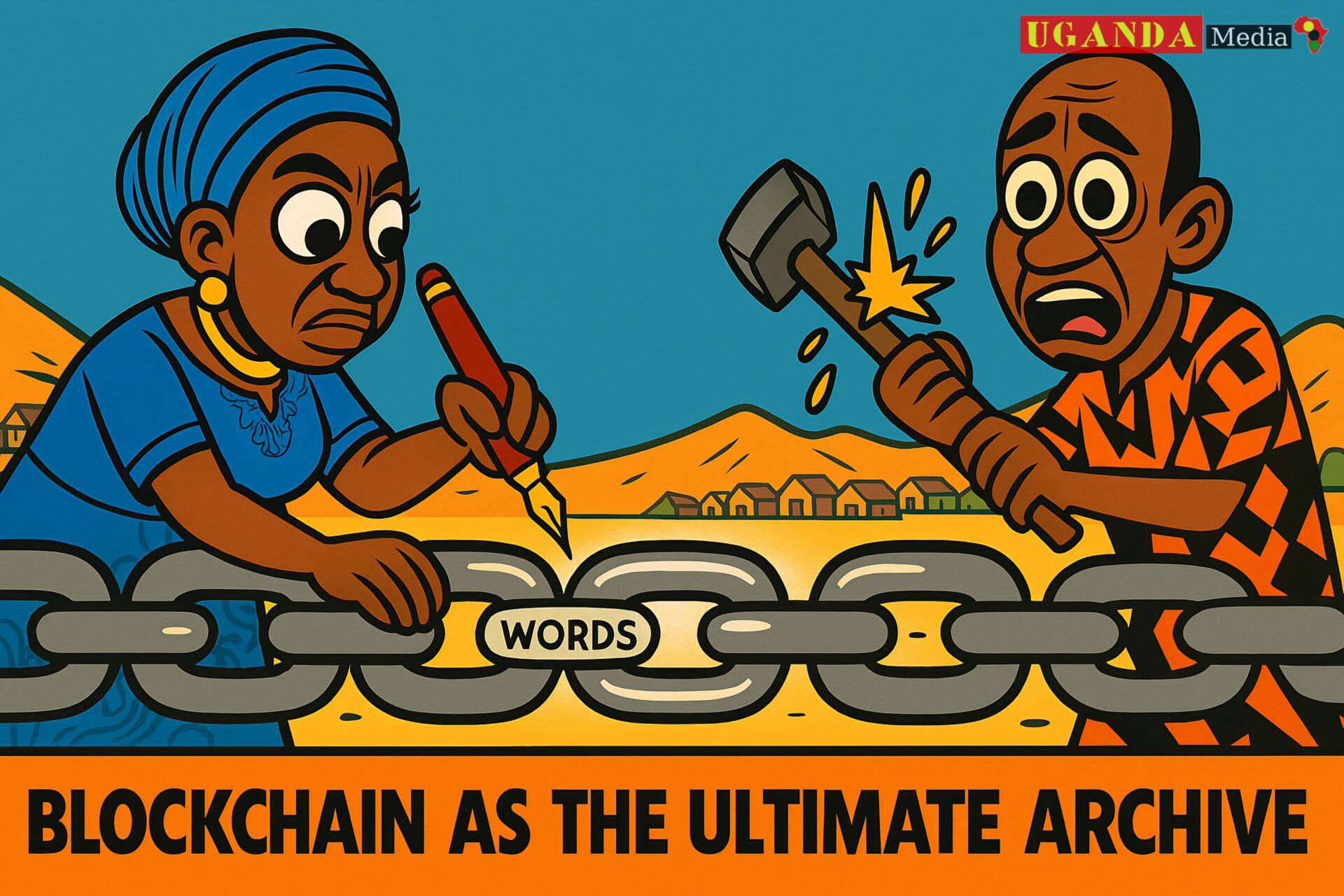

Blockchain: The Ultimate Archive—Carving Our Stories in Digital Stone

There is an old adage that “the pen is mightier than the sword,” speaking to the enduring power of the written word over transient brute force. Yet, throughout history, those wielding the sword have often sought to burn the parchment, shred the pamphlet, and silence the press. The written word, for all its power, has remained physically vulnerable. Today, a new technology emerges that fundamentally alters this ancient struggle, offering a promise that would have been considered pure fantasy to generations of scribes and dissidents: the creation of an unburnable library. Decentralised publishing platforms, built on blockchain technology, herald a future where a writer’s work, once published, becomes immutable, permanent, and immune to censorship forever. It is the act of carving our stories not in papyrus or on paper, but in the unyielding digital stone of a distributed ledger.

To grasp the revolutionary nature of this, one must first understand the fragility of our current digital havens. A website, even one protected by the Cloudflare Gambit, still exists in a centralised location. A server can be seized, a domain name registrar can be pressured, a hosting company can be compelled to take content down. It is a fortress that, while strong, still has a gate that can be besieged. The blockchain, by contrast, is not a fortress; it is the very landscape itself. When a writer publishes a poem or an essay onto a blockchain-based platform, that work is not stored in one place. It is broken into pieces, encrypted, and duplicated across a vast, global network of thousands of independent computers. There is no central server to raid, no single company to intimidate, no “off” switch for a powerful hand to press.

To grasp the revolutionary nature of this, one must first understand the fragility of our current digital havens. A website, even one protected by the Cloudflare Gambit, still exists in a centralised location. A server can be seized, a domain name registrar can be pressured, a hosting company can be compelled to take content down. It is a fortress that, while strong, still has a gate that can be besieged. The blockchain, by contrast, is not a fortress; it is the very landscape itself. When a writer publishes a poem or an essay onto a blockchain-based platform, that work is not stored in one place. It is broken into pieces, encrypted, and duplicated across a vast, global network of thousands of independent computers. There is no central server to raid, no single company to intimidate, no “off” switch for a powerful hand to press.This creates a paradigm of true, radical permanence. Imagine a detailed account of a community’s peaceful resistance to the environmental degradation of a shared forest. Published on the blockchain, this document does not simply exist online; it is timestamped and woven into an unbreakable chain of data. To censor it, a regime would not need to silence one publisher or block one website. It would need to simultaneously dismantle and rewrite the ledger on every single computer in that global network—a task that is not merely difficult, but computationally and practically impossible. The work becomes a permanent part of the historical record, as immutable as a mountain. It can be ignored, it can be denounced, but it can never be erased.

This is the ultimate form of security for the people’s history. It is a direct challenge to the power of any institution—be it corporate or state—that seeks to control the narrative by deciding what is remembered and what is forgotten. It is a decentralised, collective act of memory, a system where the people themselves, through their distributed computers, become the guardians of their own stories. It ensures that the testimony of a teacher in a remote village, the chronicle of a workers’ strike, or the collected poems of a generation will survive any attempt to airbrush them from existence.

For the exiled Ugandan writer, this is more than a technological novelty; it is the dawn of a new form of literary sovereignty. It is the power to say, “This was written. This happened. This truth exists,” and to know that this statement is backed by the unassailable mathematics of a global consensus. The pen has not just become mightier than the sword; it has become eternal. We are no longer just writing for today; we are inscribing our truths into the permanent, democratic archive of human experience, ensuring that the story of our land and our people will echo, uncensored and untampered with, for all time.

Real-World Example: The Persistence of ‘Banga’—A Story That Cannot Be Uprooted

There is an old adage which states, “you cannot kill a story by cutting off the teller’s head.” This speaks to the resilient, almost viral nature of truth once it has been released into the world. In our contemporary context, blockchain technology provides this ancient wisdom with a formidable, unassailable body. To understand its practical power, let us imagine a satirical blog, The Kampala Cactus, and follow its journey from a mere idea to an immutable part of Uganda’s digital landscape.

The Kampala Cactus is founded on a simple, subversive principle: to chronicle the ironies of power with the sharp wit of a thorn. Its name is itself a metaphor—a resilient plant that thrives in arid conditions, its deep roots making it nearly impossible to eradicate. It publishes sharp, allegorical tales. One week, it might feature a story about a mighty lion who declares all the water in the Savannah his personal property, only to find the other animals have learned to tap a hidden, communal aquifer. It could portray a grand project to construct a staircase to the moon, which is funded by taxes collected from the village’s poorest farmers, in a satirical manner in another week.

The Kampala Cactus is founded on a simple, subversive principle: to chronicle the ironies of power with the sharp wit of a thorn. Its name is itself a metaphor—a resilient plant that thrives in arid conditions, its deep roots making it nearly impossible to eradicate. It publishes sharp, allegorical tales. One week, it might feature a story about a mighty lion who declares all the water in the Savannah his personal property, only to find the other animals have learned to tap a hidden, communal aquifer. It could portray a grand project to construct a staircase to the moon, which is funded by taxes collected from the village’s poorest farmers, in a satirical manner in another week.Initially, the blog gains traction on social media, but soon faces the predictable tyranny of the algorithm. Posts are mysteriously demoted in feeds, labelled with “fact-checking” warnings for its allegorical fiction, and its reach is systematically throttled. The state-affiliated media condemns it as “unpatriotic fiction.” Powerful individuals, the subjects of its subtle critiques, issue furious denouncements. Under normal circumstances, this would be a death sentence. The hosting provider would receive intimidating legal letters, the domain would be seized, and the Cactus would be wiped from the web, its thorns plucked one by one.

But the Cactus is different. Its writers, understanding the nature of modern censorship, have published it on a decentralised blockchain platform. The moment each story is posted, it is encrypted, time-stamped, and broken into fragments that are distributed across a global network of thousands of independent computers. There is no headquarters to raid, no central server to unplug, no single company to intimidate.

The regime’s censors now face a problem of an entirely new order. They can block access to the specific website address within Uganda, much as one might put up a sign to hide a tree. But they cannot cut the tree down. The stories of The Kampala Cactus are not stored in one place; they are the forest itself. To remove a single story, they would have to commandeer and rewrite the entire global ledger simultaneously—a task as futile as trying to drain Lake Victoria with a teaspoon.

Consequently, the blog persists. Its stories are mirrored on other sites, shared via encrypted channels, and read aloud in private gatherings. Each satirical piece becomes a digital seed, blown on the winds of the internet, finding fertile ground in the minds of readers both at home and abroad. The regime’s condemnation does not erase it; it merely adds another layer to the story, becoming part of the very satire it seeks to suppress.

This is the ultimate power of this technology. The Kampala Cactus demonstrates that in the digital age, a story can be made as permanent as a geological feature. It ensures that the critical voice, the satirical jab, and the uncomfortable truth become permanent features of the public record. They can be ignored, they can be denounced, but they can never be made to have never existed. The storyteller may be silenced, but the story, once inscribed in the unbreakable chain of the blockchain, lives on, forever.

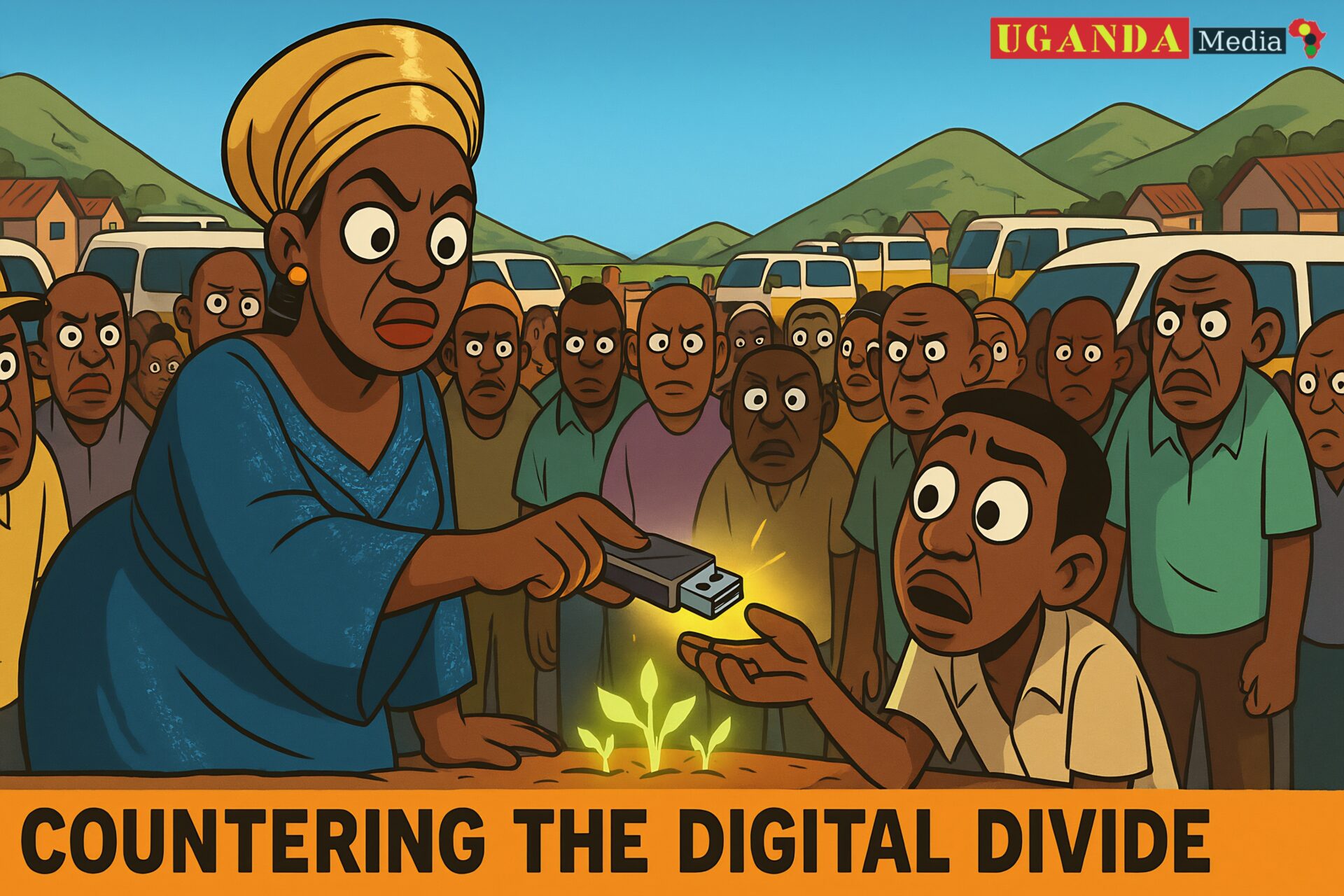

Countering the Digital Divide: Sowing Seeds in Both Digital and Earthly Soil

A wise adage reminds us that “a chain is only as strong as its weakest link.” In our fervent pursuit of a digital future for Ugandan literature—a realm of blockchain fortresses and unbounded cyberspace—we must pause to consider this truth. For the most powerful, uncensorable story is rendered meaningless if it cannot reach the people whose story it truly is. A valid and crucial critique of our digital vanguard is that it risks creating a new hierarchy, excluding the vast majority of our compatriots who remain on the wrong side of the digital divide: the farmer in Nakaseke without a smartphone, the market vendor in Arua for whom data is a luxury, the elder in a remote Karamoja village for whom the internet is a distant rumour. To ignore this is to build a castle in the sky while the village below remains in darkness. Therefore, our mission must be resolutely twofold: to conquer the digital frontier with one hand, while with the other, we diligently seed these liberated stories back into the fertile soil of our homeland through any and every means possible.

Conquering the digital frontier is non-negotiable. It is our strategic imperative to secure our narratives in the global, permanent record, to build archives that outlive any single regime and to speak truth to transnational centres of power. This work—the building of websites, the use of encryption, the exploration of blockchain—creates the master copy from which all others can be drawn. It is the source spring.

Conquering the digital frontier is non-negotiable. It is our strategic imperative to secure our narratives in the global, permanent record, to build archives that outlive any single regime and to speak truth to transnational centres of power. This work—the building of websites, the use of encryption, the exploration of blockchain—creates the master copy from which all others can be drawn. It is the source spring.But a spring must be channelled to irrigate the fields. This is the second, equally vital part of our struggle: the clandestine, grassroots work of distribution. We must become digital rainmakers, finding ingenious ways to condense the vapour of online content into droplets that can fall on every manner of ground. This requires a return to the principles of the oral tradition and the underground network, updated for the 21st century.

The SMS Serial: A powerful, self-contained allegory about collective action can be broken into a series of SMS messages and broadcast to curated lists. A story about villagers reclaiming a stolen community well can be disseminated in ten parts, each a lesson in grassroots organisation, landing directly in the palms of hands that till the earth.

The Radio Ruse: Community radio, a lifeline for millions, remains a potent medium. Recorded readings of these digital stories, framed as “folktales from the internet” or anonymous commentaries, can be aired, their origins obscured to protect the station. The voice, carrying the subversive text, travels on airwaves far harder to censor comprehensively than a single website.

The Clandestine Courier Network: This is where the movement becomes tangible. USB drives and SD cards, small and easily concealed, become the digital equivalent of the banned pamphlet. Loaded with the collected works of exiled writers, PDFs of satirical blogs, and audio recordings of poems, these tiny devices can be distributed through trusted networks—teachers, students, market traders, and boda boda riders. They are the seeds passed from hand to hand, to be planted in internet cafés, local libraries, and personal devices, creating offline archives in the very heart of our communities.

This dual approach recognises that liberation is not a singular act but a multi-front endeavour. It refuses to abandon the many for the sake of the few. It understands that true strength lies in a chain that connects the unassailable archive in the cloud to the whispered story in the village, the blockchain to the bush track. By working both frontiers simultaneously, we ensure that our literature does not become a relic for the global elite, but remains a living, breathing weapon in the hands of the people. We strengthen every link, ensuring that the story of Uganda is not only preserved for eternity, but is also alive and potent in the daily struggle of its people.

Preserving Oral Traditions Digitally: Weaving the Spoken Word into the Eternal Tapestry

There is an old adage which teaches us that “when an elder dies, a library burns to the ground.” For generations in Uganda, this has been the fragile reality of our oral heritage. Our richest libraries were not built of stone and mortar, but of memory and breath. The epic poems of the Acholi, the cautionary tales of the Baganda, the wise proverbs of the Basoga—these were living, breathing entities, passed from one generation to the next in the flickering light of an evening fire. Yet, with the passing of each elder, with the disruption of communities, and with the relentless tide of a homogenising modernity, countless volumes of this intangible library have turned to ash, lost to time forever. But a profound reversal is at hand. The digital space, often considered cold and impersonal, has emerged as the great preserver. It offers us the means to not only record but to immortalise our oral traditions, ensuring that the voice of the storyteller, in all its nuanced cadence and emotional power, outlives the teller and becomes a permanent inheritance for all humanity.

This is far more than simple archiving; it is an act of radical cultural preservation. To capture a folk tale digitally is to do more than transcribe its text. It is to preserve the rhythm of the language, the melody of the recitation, the pause for dramatic effect, the laughter of the audience, and the sigh of collective understanding. A written version of a story about the cunning hare is one thing; a high-fidelity audio recording of a grandmother telling it, her voice imbued with a lifetime of wisdom and wit, is an entirely different, far richer cultural artefact. It captures the context, the performance, and the communal spirit in which the story lives and breathes. These digital archives become a sanctuary for our collective soul, a place where the spirit of our ancestors is not a fading memory but an audible, present voice.

This is far more than simple archiving; it is an act of radical cultural preservation. To capture a folk tale digitally is to do more than transcribe its text. It is to preserve the rhythm of the language, the melody of the recitation, the pause for dramatic effect, the laughter of the audience, and the sigh of collective understanding. A written version of a story about the cunning hare is one thing; a high-fidelity audio recording of a grandmother telling it, her voice imbued with a lifetime of wisdom and wit, is an entirely different, far richer cultural artefact. It captures the context, the performance, and the communal spirit in which the story lives and breathes. These digital archives become a sanctuary for our collective soul, a place where the spirit of our ancestors is not a fading memory but an audible, present voice.Furthermore, this digital preservation is a deeply political act of decentralising cultural ownership. For too long, the curation, and interpretation of African history and culture have been centralised in foreign institutions or in the hands of state-sponsored bodies that promote a singular, sanitised national narrative. By taking it upon ourselves to record and archive these traditions, we, the people, reclaim the right to define our heritage. A community in the Rwenzoris can record its mountain songs and upload them to a distributed storage network, ensuring that their unique cultural expression is not diluted or misrepresented. This is a bottom-up construction of history, a collective project where the people themselves are the archivists, historians, and guardians of their own identity. It prevents any central authority from holding a monopoly on our past.

The potential for revival and re-contextualisation is boundless. These digitised oral traditions can be remixed into contemporary music, providing the bedrock for a new, authentically Ugandan sonic landscape. They can be animated and shared with children, both at home and in the diaspora, creating a living bridge to their cultural roots. They can be studied by scholars worldwide, not as dead relics, but as living philosophies. In this, the digital realm does not kill the oral tradition; it liberates it from the constraints of geography and mortality. It allows the voice of the elder, once confined to their village, to now echo through the global village, ensuring that the library does not burn, but is instead translated into a constellation of light, forever visible, forever accessible, and forever a source of strength for the people from whom it sprang.

Monetisation and Patronage: Cultivating a New Harvest for the Writer’s Labour

There is an enduring adage which states, “he who pays the piper calls the tune.” For generations, the Ugandan writer seeking to live by their pen has faced a stark and often compromising reality: the piper’s paymaster has most often been the state or its connected interests. Literary grants, publishing contracts, and institutional patronage have frequently been tethered to invisible strings—strings that pull a narrative towards celebration and away from critique, towards a singular national story and away from messy, pluralistic truths. This system has forced many a writer into a form of creative sharecropping, tilling the soil of their imagination on land owned by another, with the harvest subject to the landlord’s approval. Today, however, the digital age offers a radical alternative. It allows us to break this feudal chain, creating new funding models—from global micropayments to direct patronage—that free the writer from politicised local grants and return the power of the tune to the people.

This shift represents nothing short of an economic emancipation. Digital platforms dismantle the old, centralised gatekeepers of artistic funding. A writer is no longer solely dependent on the approval of a cultural ministry panel or the favour of a publishing house with close ties to power. Instead, they can present their work directly to a global audience and say, “If you value this, support it.” This is the essence of a direct patronage model, such as Patreon or similar platforms. Here, a writer chronicling the untold history of a community’s resistance to a land grab can be sustained not by a grant that might never materialise, but by a distributed community of hundreds of supporters—a Ugandan diaspora member in London, a solidarity activist in Berlin, a fellow writer in Nairobi, and a teacher in Mbale. Each contributes a small, monthly amount, becoming a co-investor in the survival of critical thought.

This shift represents nothing short of an economic emancipation. Digital platforms dismantle the old, centralised gatekeepers of artistic funding. A writer is no longer solely dependent on the approval of a cultural ministry panel or the favour of a publishing house with close ties to power. Instead, they can present their work directly to a global audience and say, “If you value this, support it.” This is the essence of a direct patronage model, such as Patreon or similar platforms. Here, a writer chronicling the untold history of a community’s resistance to a land grab can be sustained not by a grant that might never materialise, but by a distributed community of hundreds of supporters—a Ugandan diaspora member in London, a solidarity activist in Berlin, a fellow writer in Nairobi, and a teacher in Mbale. Each contributes a small, monthly amount, becoming a co-investor in the survival of critical thought.Similarly, systems of global micropayments allow for a direct, transactional relationship between the story and its reader. A powerful, long-form investigative piece into the environmental impact of a new industrial project can be placed behind a paywall, accessible for a small, one-off fee. This transforms the act of reading from passive consumption into active sponsorship. The reader, by choosing to pay for that specific story, is casting a vote for a particular kind of journalism, for a specific brand of truth-telling. It creates a market for integrity, where the value of a story is determined not by its alignment with power, but by its resonance with a concerned and conscious public.

This is a fundamentally democratic and decentralised approach to funding the arts. It operates on a principle of mutual aid between the writer and their community, bypassing the traditional intermediaries who have so often acted as censors by proxy. It allows the writer to be accountable first and foremost to their conscience and their audience, not to a political patron. The piper is now paid by the crowd in the square, and thus plays the tunes that stir their hearts and speak to their realities—tunes of struggle, of beauty, of resistance, and of hope. In cultivating this new harvest, we ensure that the writer’s labour can truly nourish the cause of justice, building an economic foundation as independent and resilient as the spirit of the stories they tell.

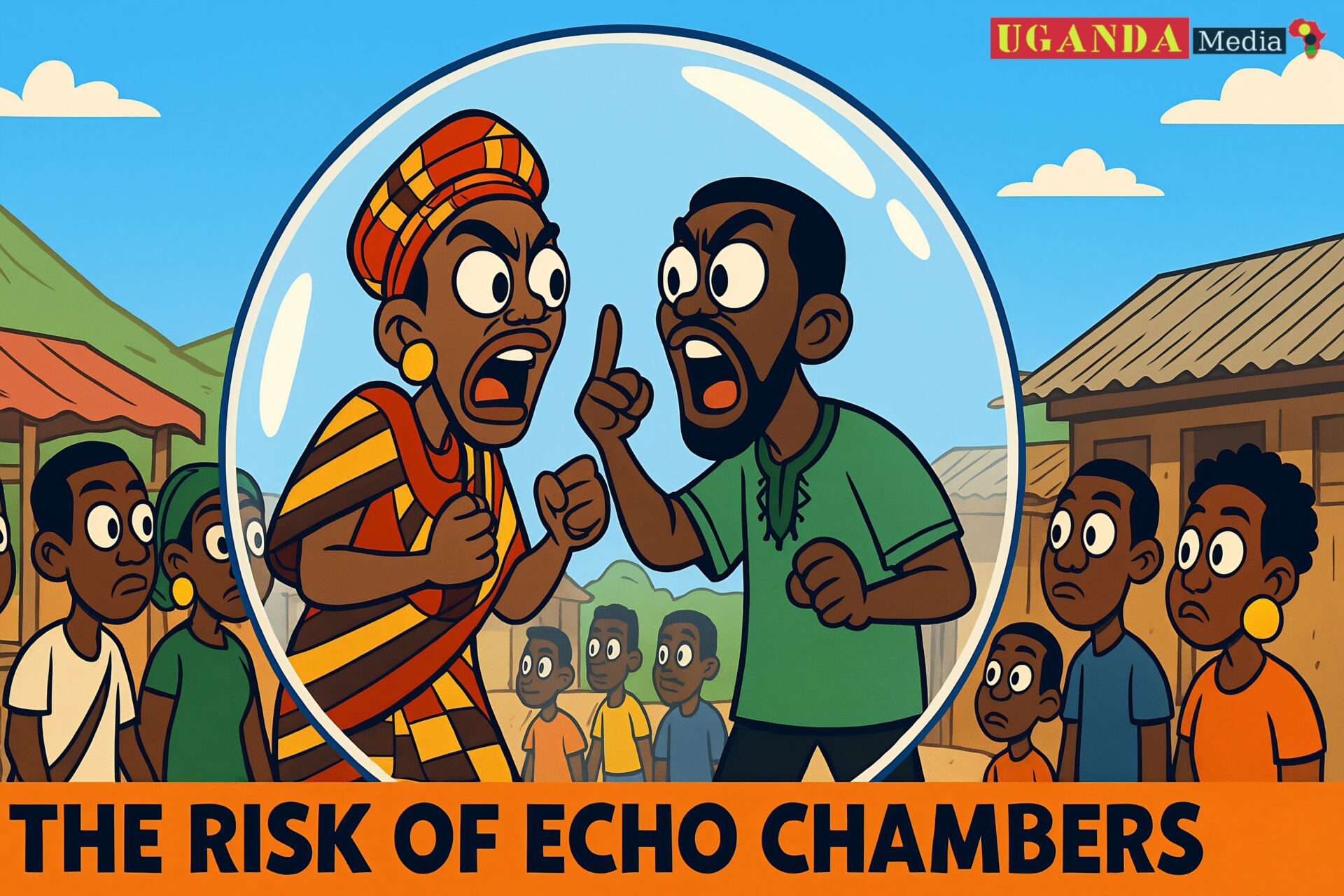

The Risk of Echo Chambers: Venturing Beyond the Choir to Preach in the Marketplace

There is a timeless adage which cautions that “a tree that falls in a forest makes no sound if there is no one there to hear it.” For the exiled writer, the digital age provides the forest, but there is a profound and seductive danger in only allowing our words to resonate among trees of the same kind. We must be rigorously wary of the digital echo chamber—the self-constructed realm where our work is celebrated, shared, and amplified solely among those already converted to our cause. While this provides essential comfort and solidarity, it is a strategic cul-de-sac. If our literature is to be a tool of genuine transformation and not merely a balm for the already aggrieved, our digital strategies must be cultivated with the cunning to reach beyond our own ranks, to algorithmically and deliberately target those sitting on the fence, both within Uganda’s borders and in the international court of public opinion.

The echo chamber is a comfortable fortress. Its walls are built by algorithms designed to show us more of what we already like and agree with. Inside, our critiques of power are met with enthusiastic affirmation; our allegories are instantly understood. Yet, while we are fortifying this citadel, the vast majority of our society—the wavering civil servant, the apolitical market vendor, the student grappling with conflicting narratives, the international observer bombarded with state propaganda—remains outside its walls. To speak only within the chamber is to have a vibrant, powerful conversation in a soundproofed room. The falling tree of our truth makes no sound in the wider world, and thus effects no change.

The echo chamber is a comfortable fortress. Its walls are built by algorithms designed to show us more of what we already like and agree with. Inside, our critiques of power are met with enthusiastic affirmation; our allegories are instantly understood. Yet, while we are fortifying this citadel, the vast majority of our society—the wavering civil servant, the apolitical market vendor, the student grappling with conflicting narratives, the international observer bombarded with state propaganda—remains outside its walls. To speak only within the chamber is to have a vibrant, powerful conversation in a soundproofed room. The falling tree of our truth makes no sound in the wider world, and thus effects no change.Therefore, our approach must be one of strategic outreach, a form of intellectual cultivation designed to sow seeds in less fertile, but far more consequential, ground. This requires a sophisticated understanding of the very digital tools we often critique. We must learn to speak the language of the algorithm not as supplicants, but as tacticians. This means:

Mastering the Art of the Keyword: We must frame our narratives using the vocabulary of the undecided. A complex analysis of economic dispossession might also be tagged with terms related to “youth unemployment” or “market stability,” intercepting those searching for practical solutions rather than overt political critique.

Engaging the Visual Grammar of the Mainstream: A powerful, text-heavy manifesto may be the core of our work, but its essence must be distilled into compelling visuals, short video clips, or accessible infographics that can travel on platforms favoured by a broader, less politically engaged audience. We must translate our complex truths into a vernacular that can stop the scroll of a casual observer.

Building Bridges, Not Barricades: Our work should condemn and propose; not only critique, but also envision. By articulating a positive, compelling vision of community, shared prosperity, and cultural vitality, we can appeal to the universal yearning for a better life, a message that resonates far beyond the circles of the already politicised.

This is not a dilution of our message, but a strategic amplification of it. It is the difference between a monk painstakingly illuminating a manuscript in a remote monastery and a town crier standing in the bustling market, adapting their message to capture the attention of the merchant, the farmer, and the artisan alike. Our goal is not simply to reassure the choir of their faith, but to convert the ambivalent in the marketplace. We must ensure that the tree of our truth does not fall in an empty forest, but that its sound shakes the very foundations of the fences upon which, so many are, perched, encouraging them to finally, and decisively, step onto the side of a more just and equitable future.

Collaboration Across Borders: Weaving a Tapestry Too Vast to Confine

There is an enduring adage which reminds us that “a single thread may be weak, but woven together, we form a tapestry that cannot be torn.” For the exiled Ugandan writer, this wisdom illuminates the path beyond mere survival towards a new, collective power. Where once exile meant isolation—a single thread snipped from the national loom—the digital era has gifted us a loom of continental scale. We can now, with a clarity once unimaginable, collaborate in real-time with artists in Nairobi, editors in London, and filmmakers in Lagos. This is not merely convenience; it is the active, conscious weaving of a powerful Pan-African creative network, a tapestry of dissent and affirmation so vast and interconnected that no border can contain it.

This collaborative potential shatters the very idea of cultural isolation as a tool of control. A regime may succeed in physically removing a critical voice from its territory, hoping to silence it. But it cannot remove Uganda from the African story. Through digital collaboration, the exiled writer’s work is continually re-rooted in a broader, shared soil. A poem written in a small flat in Berlin about the resilience of Ugandan market women can be set to music by a producer in Accra, its rhythm infused with a West African heartbeat that gives it new resonance. A sharp social commentary on the centralisation of agricultural wealth can be adapted by a filmmaker in Nairobi into a short film, visualising the struggle in a way that speaks to the shared experiences of East African communities. The writer’s voice is not silenced; it is harmonised, amplified, and translated into new artistic languages, becoming part of a continental chorus.

This network operates on a principle of radical solidarity and mutual aid, bypassing the traditional, often Western-centric, gatekeepers of the global art world. It is a self-sustaining ecosystem of creativity. An editor in London, part of the diaspora, can offer their skills to refine a manuscript, not for profit, but to ensure a crucial story is told with the greatest possible impact. A visual artist in Cape Town can create a powerful digital painting to accompany an essay on land rights, their collaboration forming a combined work of art that is greater than the sum of its parts. This is a direct, people-to-people exchange of value and skill, building a cultural economy that is independent, resilient, and aligned with a shared vision of artistic and social liberation.

This network operates on a principle of radical solidarity and mutual aid, bypassing the traditional, often Western-centric, gatekeepers of the global art world. It is a self-sustaining ecosystem of creativity. An editor in London, part of the diaspora, can offer their skills to refine a manuscript, not for profit, but to ensure a crucial story is told with the greatest possible impact. A visual artist in Cape Town can create a powerful digital painting to accompany an essay on land rights, their collaboration forming a combined work of art that is greater than the sum of its parts. This is a direct, people-to-people exchange of value and skill, building a cultural economy that is independent, resilient, and aligned with a shared vision of artistic and social liberation.The result is a formidable, distributed narrative force. It creates a situation where to silence one Ugandan writer, a regime would have to silence the entire network—a task as futile as trying to censor the wind. The story, once released into this collaborative web, takes on a life of its own, morphing and adapting as it travels. It becomes impossible to fully erase because it exists in a thousand different forms, in a hundred different places, on a dozen different servers, all at once. We are no longer just Ugandan writers; we are artisans in a Pan-African guild of truth-tellers, weaving a tapestry of such complexity and strength that it can withstand any attempt to tear it down, ensuring our stories become part of the permanent and unassailable fabric of our continent’s conscience.

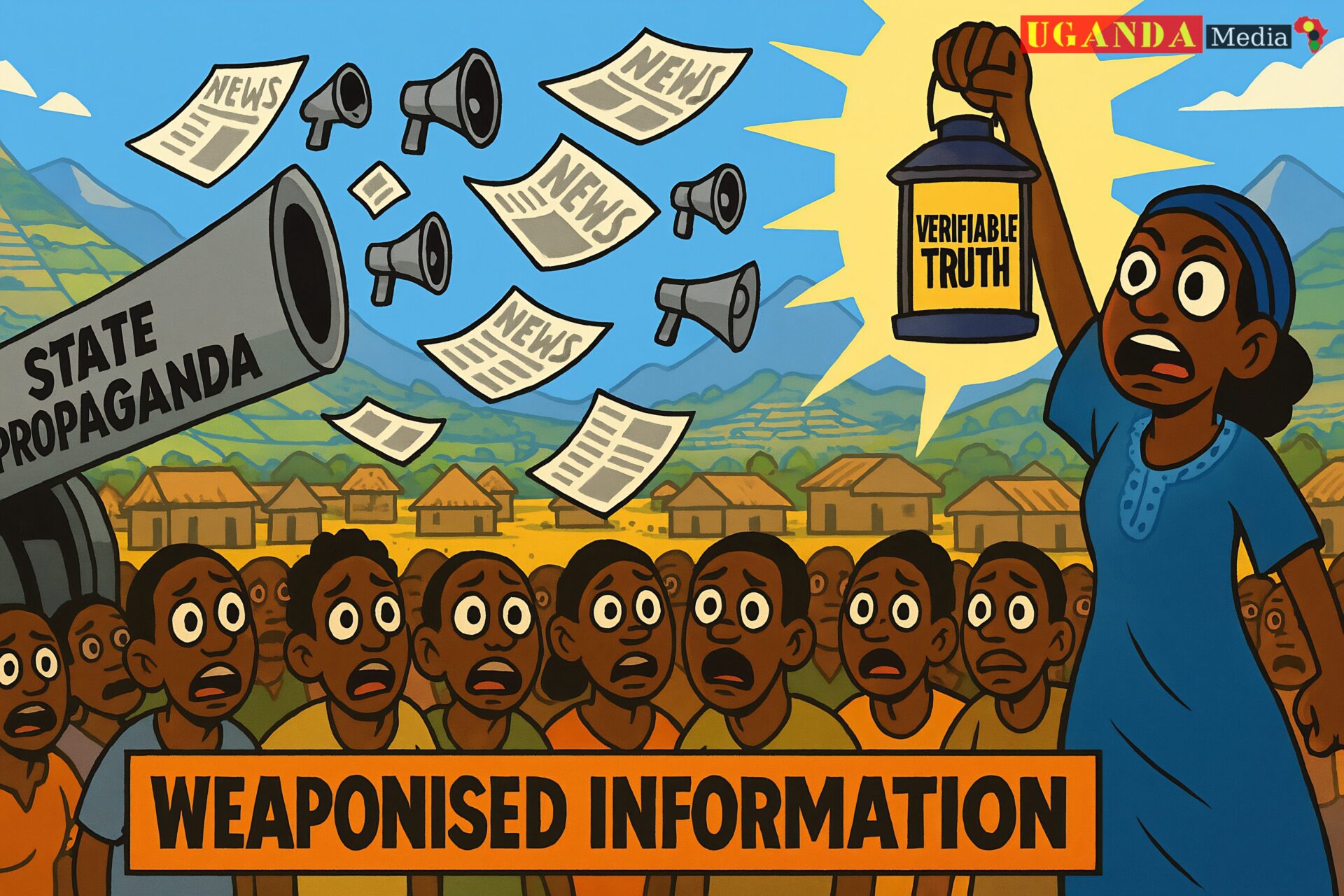

The Weaponisation of Information: Forging Our Shield in the Fire of Truth

There is a timeless adage which warns that “a lie can travel halfway around the world while the truth is still putting on its boots.” In the digital arena we now inhabit, this is not merely a philosophical observation; it is the central battlefield of our time. The very tools we champion—the instant connectivity, the vast social networks, the powerful algorithms—are not solely ours to wield. The regime, and the powerful interests it protects, are equally adept at turning this technology to its own ends, flooding the digital sphere with a sophisticated torrent of distraction, distortion, and outright falsehood. In this fog of information war, our most potent weapon is not a louder voice, but a different kind of voice altogether. Our commitment to verifiable truth, meticulous context, and credible sourcing is not just an academic principle; it is the very shield that distinguishes our literature from state-sponsored propaganda and forges a bond of unbreakable trust with the people.

The regime’s narrative is built on a foundation of convenience. It operates through spectacle and simplification. A glossy, state-produced documentary might champion a massive industrial project, highlighting its technological marvel while systematically erasing the story of the communities displaced by its footprint. Its social media armies will swarm critics not with counter-arguments, but with ad hominem attacks and a cacophony of alternative facts, designed to exhaust and confuse. Their goal is not to win a debate based on evidence, but to dismantle the very idea that evidence matters, creating a cynical populace that believes no narrative is trustworthy.

The regime’s narrative is built on a foundation of convenience. It operates through spectacle and simplification. A glossy, state-produced documentary might champion a massive industrial project, highlighting its technological marvel while systematically erasing the story of the communities displaced by its footprint. Its social media armies will swarm critics not with counter-arguments, but with ad hominem attacks and a cacophony of alternative facts, designed to exhaust and confuse. Their goal is not to win a debate based on evidence, but to dismantle the very idea that evidence matters, creating a cynical populace that believes no narrative is trustworthy.Our literature must stand in stark opposition to this corrosive chaos. We must be the archivists of reality, the cartographers of the authentic. This demands a rigour that is, in itself, a radical act. It means that when we chronicle the decline of a public service, we ground it in budget analyses and testimonies from those on the front lines—the nurses, the teachers, the service users. When we write a fictional allegory about corruption, its power must derive from its resonance with widely witnessed, documentable patterns of behaviour, not from wild invention. We must be the writers who cross-reference, who provide sources, who admit uncertainty, and who correct our own errors with transparency. This scrupulous fidelity to truth builds a foundation of credibility that no state-sponsored fiction can ever hope to achieve.

This commitment transforms our work from mere commentary into a vital public utility. In a landscape saturated with manipulative noise, our stories become a refuge for those seeking clarity. The teacher in a remote town, the student at university, the journalist working under constraints—they learn to turn to our work not for easy answers, but for a rigorously constructed portrayal of their reality. We provide the intellectual tools for them to dismantle the official lies themselves. We are not simply telling them what to think; we are showing them, through our own example, how to think critically.