An Introduction to Uganda’s Political Theatre: Spectacle, Strategy, and a Stalled Struggle

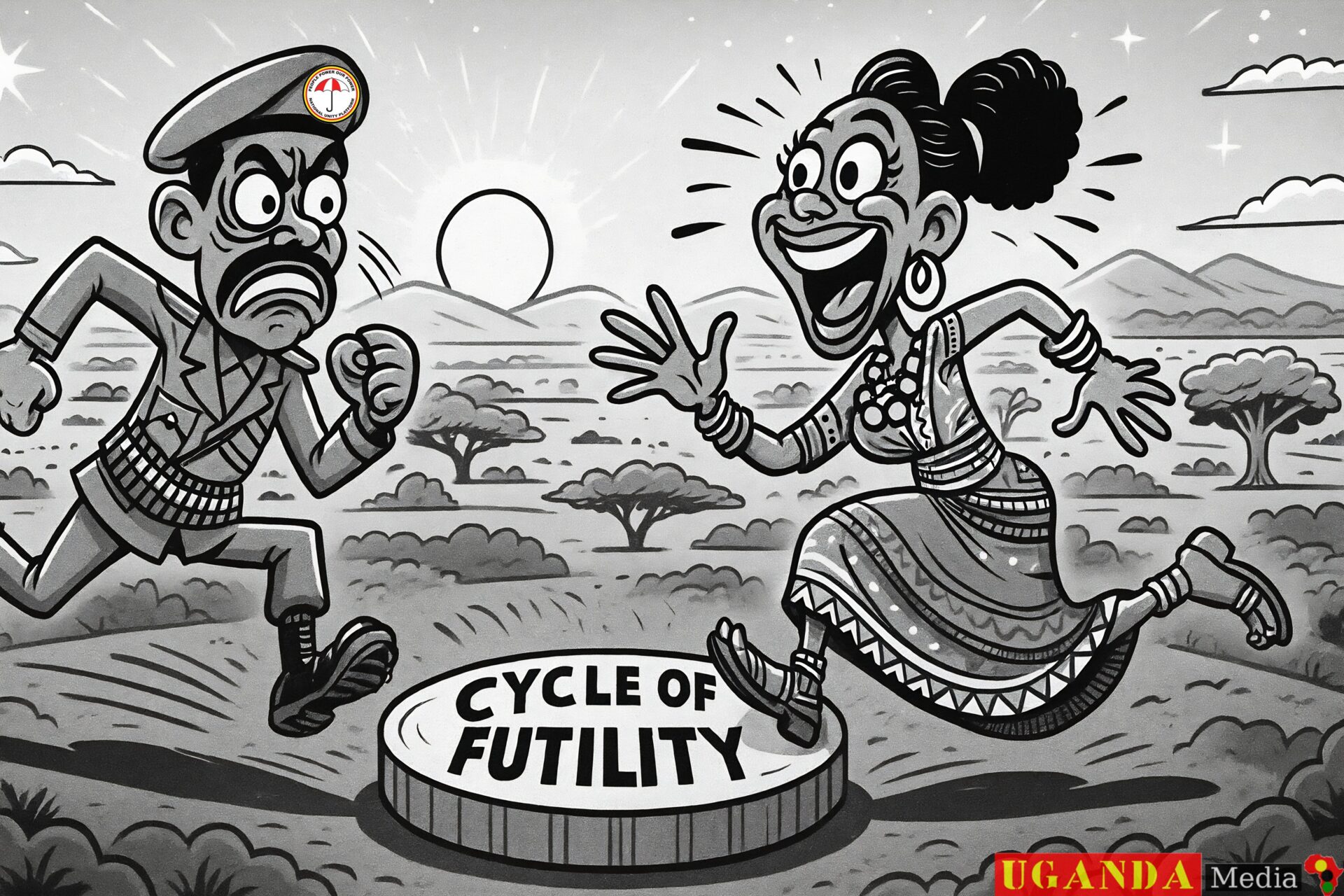

Beneath the vibrant canopy of Uganda’s political landscape, a compelling and often tragic drama unfolds. It is a story of immense hope and profound disillusionment, where the fiery rhetoric of liberation collides with the gritty realities of power, and where history seems to echo in a disheartening loop. This analysis delves into the heart of this complex narrative, examining the formidable challenge posed to President Yoweri Museveni’s long-standing National Resistance Movement (NRM) and the paradoxical performance of its chief rival, the National Unity Platform (NUP) led by Bobi Wine.

We explore the stark contradictions that define the current opposition: the spectacle of mass rallies set against the silence of 200 constituencies where no NUP parliamentary candidate stood; the potent symbolism of the red beret contrasted with administrative farces like botched nominations; and the passionate calls for change that falter in the face of rejected alliances and a substance deficit in governance planning. Through the lens of poignant personal stories, like that of Mathias Walukaga and his 300 million shilling party card, we interrogate the commodification of political hope and the internal fractures within the movement.

Furthermore, this scrutiny is grounded in Uganda’s fraught political history, notably the disputed 1980 election—a foundational event that birthed the current regime and established a precedent where the rule of law was bypassed for the gun. We trace how this legacy and the tribal targeting of the subsequent bush war continue to shape the nation’s socio-political fabric, asking whether today’s opposition is challenging a system or inadvertently perpetuating its methods.

From the rapid ascent of figures like Joel Ssenyonyi to the critical warnings of veterans like Dr. Kizza Besigye, this is a comprehensive examination of why Uganda’s struggle for political change remains entrenched in a cycle of captivating performance, yet frustrating stagnation. It is an essential read for anyone seeking to understand the intricate, and often unsettling, dynamics of power and resistance in modern Uganda.

The Great Ugandan Political Circus: Tears, Tiaras, and 300 Million Shilling Party Cards

Introduction

Under the relentless Kampala sun, where the air smells of roasted maize and revolution, Uganda’s political theatre is staging its most extravagant, tragic, and downright peculiar season yet. It’s a production where clowns don military fatigues, would-be kings sell dreams for a fortune, and veteran ringmasters watch from marble-tiled mansions, sipping waragi with a wry smile. The plot, tangled in claims of liberation and accusations of elaborate joke-telling, has left a trail of broken wallets, broken promises, and a nation wondering if it’s watching a revolution or a particularly brutal comedy sketch. At the heart of it all lies a simple, painful question from a man named Mathias Walukaga: “How does my life’s savings become ‘struggle money’ with nothing but a plastic card to show for it?” Buckle up; this is not your typical political analysis. This is the tale of the show that never quite gets on the road.

The Body: Twenty Rings of the Circus

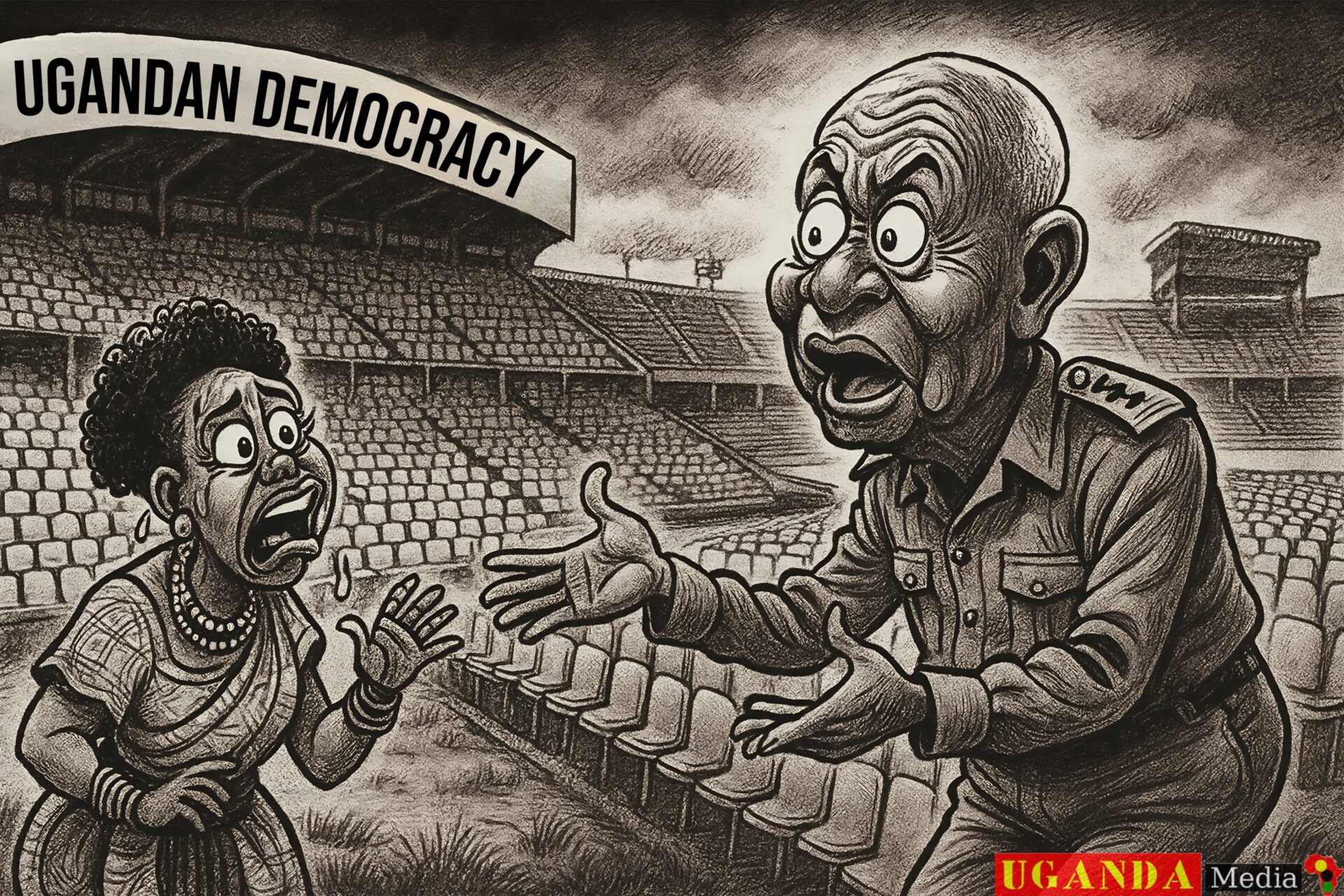

The Spectacle of Absence: A Theatre of Empty Chairs

In the sweltering political amphitheatre of Uganda, where the stage is set for a duel of titans, the most striking performance of the latest season has been one of profound, echoing silence. It is the spectacle of the empty chair. The National Unity Platform (NUP), heralded by its crimson-clad devotees as the inevitable new dawn, presented a curious opening act: a stage largely devoid of its principal players. Failing to field candidates in 200 of 458 parliamentary constituencies and abandoning the local council arena in 90 districts is not merely a tactical retreat; it is a dramatic void, a deafening non-statement that speaks volumes about the state of the challenge to the ageing dictator’s enduring reign.

To the weary voter in Arua or Moroto, this absence is not a strategic masterstroke whispered about in Kampala’s air-conditioned salons. It is a palpable emptiness. It is the poster that was never pasted, the rally that never echoed through the trading centre, the door that was never knocked upon. The regime’s machinery, ever-grinding and omnipresent, faced not a contender in these places, but a ghost. This is the political equivalent of preparing for a heavyweight bout only for one’s opponent to send their robe and gloves into the ring, unattended. The bell rings, and there is only one fighter swinging, his blows landing on empty air before the captivated, confused gaze of the nation. As the old adage goes, you cannot win the game if you forfeit the match before a single ball is bowled.

This vacuum is more than an organisational failure; it is a sinister gift, meticulously wrapped and handed to the dictatorship. Each uncontested seat is a brick mortared more firmly into the wall of the regime’s legitimacy. It allows the narrative to be spun in State House bunkers and pro-regime newsrooms: “See? Even they cannot find a soul brave or credible enough to stand in these places. Our support is total, organic, unchallenged.” The 43 NRM MPs who waltzed into office unopposed are not just legislators; they are living trophies in a museum of manufactured consent, their victories framed not as a failure of opposition but as a testament to the dictator’s incontestable reach.

This vacuum is more than an organisational failure; it is a sinister gift, meticulously wrapped and handed to the dictatorship. Each uncontested seat is a brick mortared more firmly into the wall of the regime’s legitimacy. It allows the narrative to be spun in State House bunkers and pro-regime newsrooms: “See? Even they cannot find a soul brave or credible enough to stand in these places. Our support is total, organic, unchallenged.” The 43 NRM MPs who waltzed into office unopposed are not just legislators; they are living trophies in a museum of manufactured consent, their victories framed not as a failure of opposition but as a testament to the dictator’s incontestable reach.The reasoning whispered in NUP’s defence—of resource constraints, of strategic consolidation, of fearing regime violence—holds a bitter kernel of truth under this police state. Yet, to the grandmother in Kasese who saved her shillings for a party card, or the youth in Gulu who daubs graffiti on a midnight wall, this calculus of absence feels like a betrayal. It transforms a movement built on the promise of frontal, defiant energy into a spectacle of shadow-boxing. It suggests a liberation struggle that is curiously afraid of the battlefield, preferring the safety of grand pronouncements in urban strongholds to the gritty, dangerous work of contesting power in every village and parish. The struggle begins to resemble a beautifully choreographed stage play, thrilling in its contained eruptions, but never threatening to break the fourth wall and truly engulf the entire theatre.

This is where the poignant tragedy of this empty theatre truly bites. It leaves a loyalist like the now-fabled Mathias Walukaga not just financially ruined, but spiritually stranded. He sold his world for a front-row seat to a revolution, only to find the stage dark and the directors unavailable for comment. His 300 million shilling question hangs in the humid air, unanswered: what is the value of a ticket to a show that refuses to go on tour?

This is where the poignant tragedy of this empty theatre truly bites. It leaves a loyalist like the now-fabled Mathias Walukaga not just financially ruined, but spiritually stranded. He sold his world for a front-row seat to a revolution, only to find the stage dark and the directors unavailable for comment. His 300 million shilling question hangs in the humid air, unanswered: what is the value of a ticket to a show that refuses to go on tour?Ultimately, the emptiness of those 200 chairs and 90 district headquarters is a mirror. It reflects the hollowing out of political hope, the transformation of a once-vibrant challenge into something that looks unsettlingly like a managed dissent. It provides the dictatorship with its most potent prop: the image of an alternative that cannot, or will not, truly present itself. The regime’s longevity is built not just on the strength of its own grip, but on the visible weakness of the hand that seeks to pry it loose. In this great Ugandan political theatre, the most powerful act may yet be the one where the lead actor, by refusing to appear for most of the performance, convinces the audience that the play was never really worth staging at all.

The Walkover Waltz: A Choreography of Acquiescence

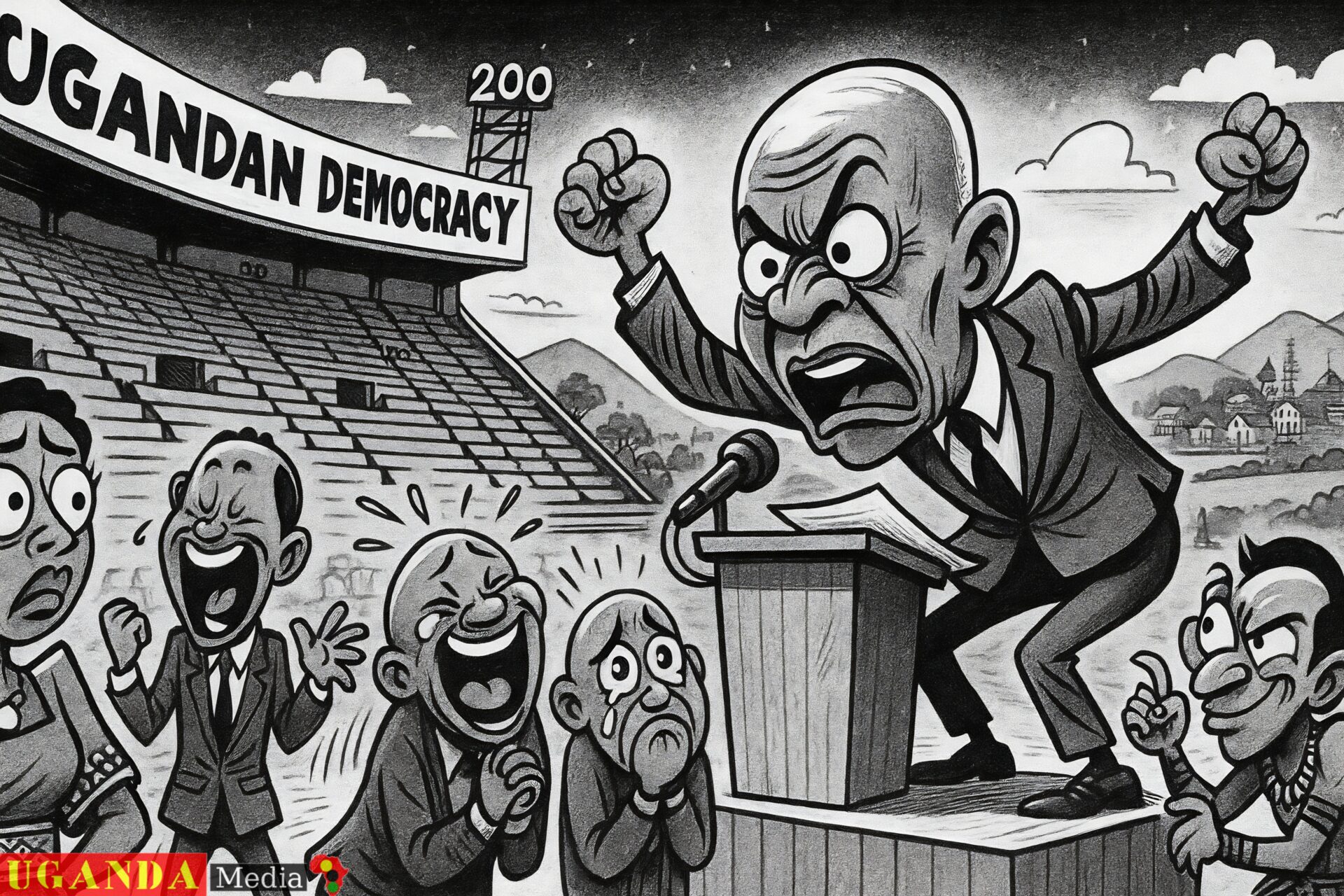

In the grand ballroom of Ugandan politics, the music never truly stops. It merely changes tempo. As the latest electoral cycle approached, the nation braced for the familiar, bruising dance of competition—the clash of posters, the thunder of rally speeches, the sharp, nervous energy of polling day. Yet, in a significant portion of the country, a very different performance unfolded: the silent, seamless Walkover Waltz.

While opposition strongholds vibrated with the frantic, off-rhythm scrambling of campaigns, the National Resistance Movement (NRM) apparatus in 43 constituencies engaged in a more stately, serene routine. There was no need for the vulgarity of debate or the messiness of persuasion. The outcome was a foregone conclusion, etched not in the promises of a manifesto, but in the cold calculus of power. Candidates, often already embedded in the vast architecture of the state, simply glided through the nomination process and into their parliamentary seats without a single opponent to contest their stride. Their victory speeches were composed long before a single ballot was cast, rehearsed in the quiet confidence of total control.

The contrast is where the farce curdles into something more disquieting. The National Unity Platform (NUP), the principle chorus of dissent, returned a tally of zero in this particular dance. Not a single unopposed victory. This is not a badge of honour earned through fierce contest, but a stark statistical void. It paints a picture of a challenge that is geographically contained, surgically permitted to exist in specific urban and regional pockets where the cost of outright suppression is deemed too high, while vast swathes of the national territory are rendered what the regime would call ‘politically tranquil.’ The opposition’s battle cry, loud and furious in Kamwokya, echoes into a vast, silent void across the northern savannah, the eastern highlands, and the western farmlands.

This waltz is not an accident of popularity; it is a sophisticated tool of domination. A walkover is the ultimate political luxury, granted by a system that has mastered the art of pre-emptive neutralisation. It can be achieved through the chilling effect of past violence, the co-opting of potential rivals with patronage, the bureaucratic strangulation of nomination papers, or the simple, unspoken understanding that standing against the movement is a futile, if not dangerous, endeavour. Each unopposed seat is a brick in a wall, a declaration that in this constituency, the dictator’s ecosystem is so complete that political competition is an extinct concept.

This waltz is not an accident of popularity; it is a sophisticated tool of domination. A walkover is the ultimate political luxury, granted by a system that has mastered the art of pre-emptive neutralisation. It can be achieved through the chilling effect of past violence, the co-opting of potential rivals with patronage, the bureaucratic strangulation of nomination papers, or the simple, unspoken understanding that standing against the movement is a futile, if not dangerous, endeavour. Each unopposed seat is a brick in a wall, a declaration that in this constituency, the dictator’s ecosystem is so complete that political competition is an extinct concept.The consequence is a parliament whose very composition is a pre-scripted narrative. These 43 MPs enter the House not as representatives who have won a public argument, but as ambassadors of an immutable status quo. Their presence en masse subtly transforms the legislature from a chamber of potential debate into a theatre for the ratification of executive will. The democratic ideal of a mandate earned through public trust is replaced by the sterile reality of a seat allocated through systemic engineering.

For the ordinary Ugandan, the Walkover Waltz embodies a disempowering truth. It signals that their constituency has been judged, and found to be already spoken for. Their political agency is rendered a theoretical concept, like being asked to cheer for the only runner in a race. The old adage rings with a bitter, local truth: He who defines the terms of the debate wins it before a single word is spoken. The regime has mastered the art of defining the political terrain, making the absence of opposition not a failure of their own system, but a natural, peaceful state of affairs.

Thus, the Walkover Waltz is more than just an easy victory. It is a potent symbol of a stunted political landscape. It is the spectacle of a liberation struggle forced to dance at the edges of the ballroom, while the centre floor is occupied by those moving in perfect, unchallenged step to a tune composed decades ago in the bush, and now played on a loop by the state’s powerful orchestra. The real contest is not on the ballot in these constituencies; it is in the grim, daily struggle to keep the very idea of an alternative alive in a country where so many seats are filled by the serene, uncontested waltz of power.

The Theatre of Attire: Fabric as Prophecy and Provocation

In the meticulously staged production of Ugandan politics, where every gesture is scrutinised, and every symbol weaponised, the wardrobe choices of the principal actors are never merely sartorial. They are script. The decision by the National Unity Platform to cloak its supporters in coordinated attire of a paramilitary flavour—camouflage patterns, red berets, combat boots—is a subplot woven with such deliberate tension that it transcends fashion and enters the realm of strategic theatre. This is not about clothing; it is about crafting an image, and in doing so, scripting a potential future.

To the sympathetic eye, this uniform is a powerful piece of political semaphore. It signals discipline, a break from the often chaotic aesthetic of past opposition movements. It fosters a palpable sense of unity and collective purpose, transforming a crowd into a corps. It visually echoes the original National Resistance Army rebellion, a clever, if provocative, piece of historical cosplay meant to position the NUP as the legitimate heirs to a revolutionary legacy, framing their current struggle as a continuation of that foundational fight. For the young supporter in Kampala, the beret isn’t just fabric; it is a membership badge to a solemn, purposeful fraternity, a tangible identity in a struggle that often feels abstract.

However, in the shadows of the state’s extensive security apparatus, this same costume is read from an entirely different, and more ominous, script. Critics posit a far more calculating rationale: this attire is less a uniform for a political party and more of a carefully laid costume for a pre-written drama of state retaliation. By presenting a civilian political movement with the visual aesthetics of an insurgency, the NUP, some argue, is consciously constructing the perfect visual pretext. It provides the regime’s notoriously trigger-happy security forces with a ready-made justification for disproportionate violence. A crowd in jeans and t-shirts is clearly protesting. A crowd in berets and camouflage, moving in unison, can be labelled by state media as a “mob,” a “rebel cell,” or “terrorists in formation,” thereby legitimising a brutal response. The attire becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy of conflict.

However, in the shadows of the state’s extensive security apparatus, this same costume is read from an entirely different, and more ominous, script. Critics posit a far more calculating rationale: this attire is less a uniform for a political party and more of a carefully laid costume for a pre-written drama of state retaliation. By presenting a civilian political movement with the visual aesthetics of an insurgency, the NUP, some argue, is consciously constructing the perfect visual pretext. It provides the regime’s notoriously trigger-happy security forces with a ready-made justification for disproportionate violence. A crowd in jeans and t-shirts is clearly protesting. A crowd in berets and camouflage, moving in unison, can be labelled by state media as a “mob,” a “rebel cell,” or “terrorists in formation,” thereby legitimising a brutal response. The attire becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy of conflict.This creates a deeply cynical symbiosis. The opposition gains potent, martyrdom-inducing imagery when the inevitable crackdown occurs, feeding a narrative of peaceful supporters brutalised by a paranoid dictatorship. The dictatorship, in turn, gains a vital public relations tool to sanitise its repression for domestic and international audiences, pointing to the “military-style” gear as evidence of a threat that required neutralising. It is a macabre dance where both sides, for opposing reasons, have an interest in maintaining the illusion of an impending armed confrontation. The ordinary supporter, meanwhile, becomes an unwitting extra in this dangerous play, their clothing potentially signing a warrant for their own victimisation.

The great, unspoken tragedy lies in the likely reality of the charade. As our earlier narrator scoffed, these are overwhelmingly civilians—artists, vendors, students—whose bravery is profound but whose capacity for actual militant engagement is negligible. The beret is a symbol, not a helmet; the camouflage a pattern, not armour. They are dressed for a war they cannot and likely do not wish to fight, making the performance all the more pitiable and the potential consequences all the more grievous. They are playing a role written for them in a script where the final act is always written by the state’s monopoly on violence.

Thus, this sartorial strategy embodies a perilous gamble. It seeks to project strength and seriousness, but risks inviting the very annihilation it symbolically pretends to withstand. It speaks to a desperate need to be seen as a formidable force, yet in doing so, may be conspiring in its own framing as a legitimate target. In a political environment where perception is ruthlessly manipulated, the choice of fabric becomes a fateful one. After all, one should be wary of dressing for the part if the only other actor on stage is looking for an excuse to turn the play into a tragedy. The costume, intended as armour, may well be designing the blueprint for their own cage.

The Pantomime of Potency: Theatre Where the Stakes are Real

Beneath the blistering sun of Uganda’s political arena, a peculiar and unsettling performance unfolds. It is a spectacle of challenged strength, a public dare wrapped in the aesthetics of defiance. The anonymous narrator’s jibe cuts to a raw nerve: the suggestion that the opposition’s mobilisation, for all its visual ferocity, is a carefully choreographed display where the actors are in costume, but the script will never allow for the final, decisive scene. It is the theatrical announcement of a wrestling match, complete with grand entrances and fearsome posturing, staged in the full knowledge that the purported champions would be swiftly and brutally incapacitated by the state’s genuine heavyweights should they ever truly step into the ring.

This performance is not born of cowardice, but of a devastatingly pragmatic understanding of the imbalance of power. The regime’s security apparatus is not a fellow contestant; it is the owner of the stadium, the controller of the lights, and the final arbiter of all rules, which it can change at will. The uniformed agents of the state possess not just the physical conditioning, but the institutional sanction, the weaponry, and the profound political impunity to engage in violence not as sport, but as policy. To imagine a ‘fair fight’ between a cadre of inspired civilians and a militarised state is to misunderstand the fundamental nature of the contest.

Thus, the opposition finds itself trapped in a tragic pantomime. The donning of certain attire, the chants of defiance, the public displays of unity—these become a substitute for the direct confrontation they are structurally engineered to lose. It is a necessary, soul-corroding fiction. They must project an image of formidable resistance to maintain the morale of their supporters and sustain a narrative of challenge, yet they must simultaneously avoid crossing the invisible, shifting line that would trigger an annihilating response. Their bravery is real, but it is the bravery of the tightrope walker, not the frontline soldier; it is the courage to stand in the costume of a fighter while being acutely aware that the other side holds all the weapons.

Thus, the opposition finds itself trapped in a tragic pantomime. The donning of certain attire, the chants of defiance, the public displays of unity—these become a substitute for the direct confrontation they are structurally engineered to lose. It is a necessary, soul-corroding fiction. They must project an image of formidable resistance to maintain the morale of their supporters and sustain a narrative of challenge, yet they must simultaneously avoid crossing the invisible, shifting line that would trigger an annihilating response. Their bravery is real, but it is the bravery of the tightrope walker, not the frontline soldier; it is the courage to stand in the costume of a fighter while being acutely aware that the other side holds all the weapons.This dynamic serves the dictatorship perfectly. It allows the regime to portray its rivals as unserious—as play-actors in berets, generating sound and fury but signifying no genuine threat to the entrenched order. It transforms a political struggle into a spectacle that can be belittled. The state’s overwhelming force remains in the barracks, a silent, looming promise, while its propagandists point and laugh at the ‘impotent’ posturing of their adversaries. The message to the public is clear: these are not liberators; they are merely performers in a tragicomic show, and a dangerous one at that.

For the ordinary participant, this creates a profound psychological dissonance. They are asked to embody the spirit of a revolutionary while their hands remain empty. They channel the energy of insurrection, knowing the gates of the armoury are sealed. The adrenaline of the rally crashes against the cold wall of reality once the banners are furled. The inevitable result is a deep, politically toxic frustration—a fury that can be directed inwards, leading to internal dissolution, or outwards in sporadic, unsustainable outbursts that only justify further state repression.

In the end, this pantomime of potency is a symptom of a captured political space. It is what happens when genuine contest is forbidden, leaving only the shadow of conflict. The opposition, denied a legitimate arena to wrestle for power, is forced to mimic the appearance of a struggle they are systematically prevented from winning. The old adage warns, “Do not shake your spear at a fortress when you have only a pointed stick.” The performance, however stirring, however necessary for morale, cannot by itself bring down the walls. It is a drama of defiance staged in the courtyard of the keep, a poignant reminder that in this particular Ugandan theatre, the most critical reviews are not written by the audience, but are delivered from the battlements, in a language of pure, uncompromising force.

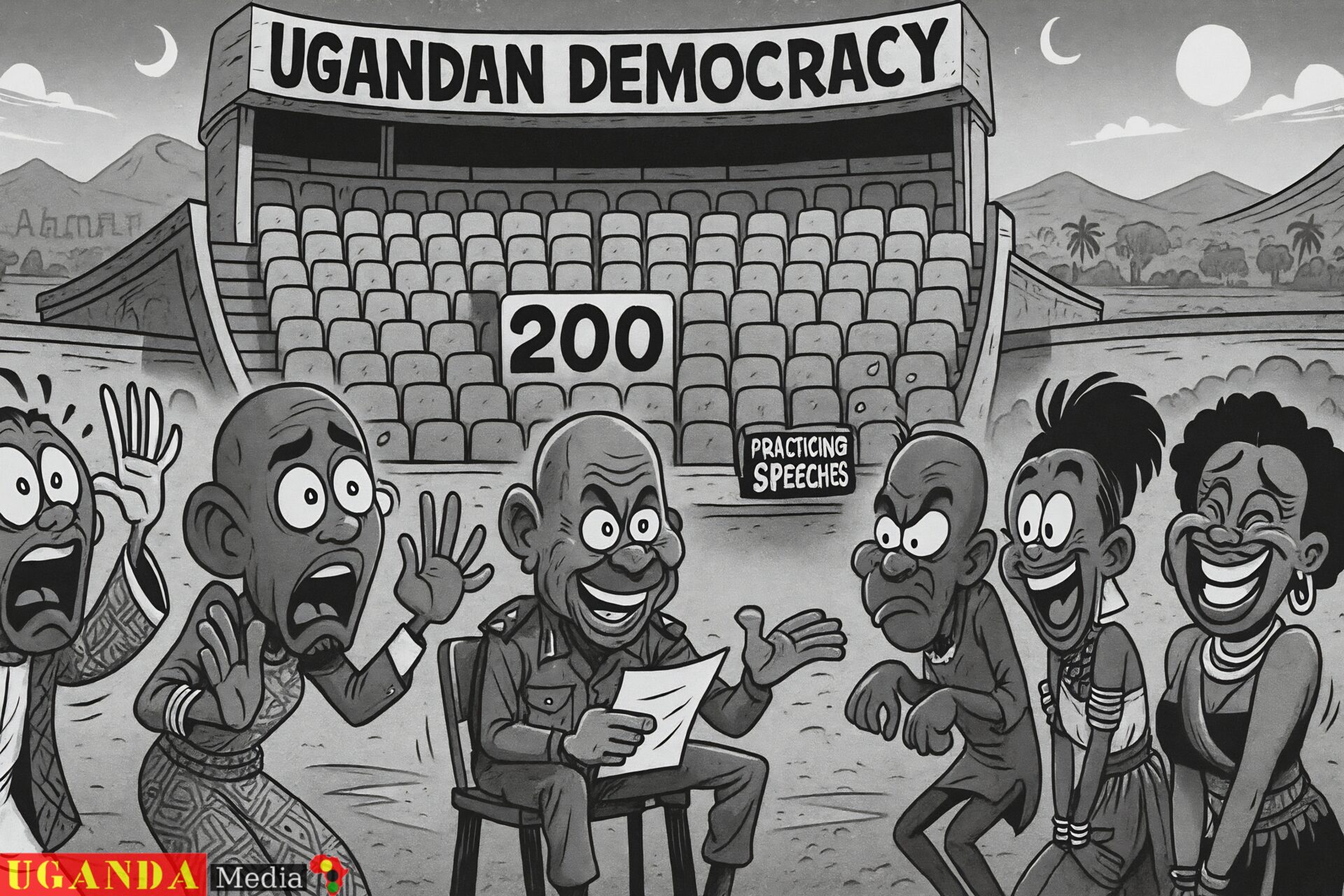

The Liberation Masquerade: When Performance Replaces Strategy

In the dense, charged atmosphere of Ugandan politics, where the yearning for change is as palpable as the humidity, a disquieting narrative has taken root. It is the accusation that the most prominent challenge to the existing order has, perhaps willingly, descended into a kind of political masquerade—a vibrant, noisy, and ultimately ceremonial performance that substitutes the hard graft of liberation with the compelling spectacle of its promise. The charge is not merely of failure, but of a conscious theatricality: that the National Unity Platform approaches the grave task of unseating a four-decade dictatorship not with a conqueror’s blueprint, but with a troupe actor’s script, precisely because the existing stage machinery makes a genuine victory implausible.

This transforms the struggle from a strategic pursuit into a symbolic pageant. The energy is not channeled into the slow, patient, and dangerous work of building an invincible national machinery—the granular structuring of networks, the meticulous legal challenges, the forging of unbreakable alliances across every district and demographic. Instead, it is poured into producing arresting moments: the dramatic motorcade, the cathartic rally where frustration finds a voice, the cultivation of a visual identity heavy with the aesthetic of resistance. The objective shifts subtly, from the operational goal of seizing state power to the performative goal of representing the idea of resistance itself. It becomes a continuous live show of dissent, playing to an audience of supporters and international observers, where applause is measured in decibels of cheers and viral social media metrics, not in electoral college votes or control of parliamentary committees.

This transforms the struggle from a strategic pursuit into a symbolic pageant. The energy is not channeled into the slow, patient, and dangerous work of building an invincible national machinery—the granular structuring of networks, the meticulous legal challenges, the forging of unbreakable alliances across every district and demographic. Instead, it is poured into producing arresting moments: the dramatic motorcade, the cathartic rally where frustration finds a voice, the cultivation of a visual identity heavy with the aesthetic of resistance. The objective shifts subtly, from the operational goal of seizing state power to the performative goal of representing the idea of resistance itself. It becomes a continuous live show of dissent, playing to an audience of supporters and international observers, where applause is measured in decibels of cheers and viral social media metrics, not in electoral college votes or control of parliamentary committees.Such an approach, critics argue, creates a convenient symbiosis with the very regime it claims to oppose. The dictatorship, a veteran of political theatre, understands spectacle well. It can tolerate, and even indirectly encourage, a contained, spectacular opposition. A lively masquerade confined to specific times and places is preferable to a silent, organising, underground force. It allows the state to point to the noise as evidence of a vibrant democracy, while simultaneously using the more exuberant elements of the performance to justify its own enduring narrative of necessary stability and security. The regime becomes the sober, paternal stage manager, reluctantly tolerating the raucous play until the actors, as they inevitably do, ‘overstep.’

For the citizenry, this spectacle breeds a corrosive duality. They are at once the audience, thrilling to the show of defiance, and the victims of its inherent limitations. They invest hope, money, and occasionally their safety into a production that provides emotional catharsis but leaves the fundamental set design of the state untouched. The promise of liberation begins to feel like a recurring season of a popular drama—enthralling in its weekly conflicts, but never culminating in a finale that changes the world of the characters. The political horizon becomes a stage flat, painted to look like a future.

This performative struggle inevitably neutralises its own potential. It expends its capital on maintaining the show—the logistics of rallies, the production of merchandise, the management of the leading player’s image—leaving little for the less glamorous, foundational work. It attracts those drawn to the spotlight of protest rather than the grey discipline of governance. The movement risks becoming a subculture of resistance, complete with its own fashion and folklore, rather than a credible alternative government-in-waiting.

Thus, the tragedy of this grand performance lies in its self-fulfilling prophecy. By adopting the methods of spectacle over substance, the challenge inadvertently validates the dictatorship’s permanence. It creates a dynamic where the fight itself becomes a fixture of the political landscape, a controlled pressure valve, rather than an existential threat to the system. The old saying proves bitterly apt: you cannot break down a fortress by throwing a splendid party at its gates. The music and dance may lift spirits and draw a crowd, but the walls remain unmoved, their guards watching the festivities with a mix of amusement and strategic calculation, confident that when the last song fades, the gates will still be in their keeping, and the keys still on their belt.

The Forge of One’s Own Chains: Crafting the Caricature of Chaos

Within the high-stakes theatre of Ugandan politics, where every act is scrutinised, and every image weaponised, a particularly unsettling scene appears to be playing out. It is the allegation of a conscious self-caricature, a deliberate shaping of one’s public persona into the very monster the ruling regime needs it to be. Beyond the immediate rallies and rhetoric, a second, more insidious motive is whispered: that elements within the opposition, through a calculated or perhaps reckless embrace of certain methods, are engaged in painting their own movement—and by extension, all dissent—with the broad brush of volatility, frivolity, and inherent ungovernability. This is not merely poor public relations; it is the strategic, if self-defeating, adoption of a villainous makeover.

This transformation operates on a dual stage. Domestically, the consistent presentation of politics as primarily spectacle—characterised by gestures easily framed as aggressive, rhetoric that prioritises heat over light, and organisational decisions that appear chaotic—feeds directly into the dictatorship’s most potent narrative. The state’s vast propaganda machinery need not invent a threatening, chaotic opposition; it can simply amplify the one on display. Each instance of internal disarray, each flash of uncontained fury, each symbolic adoption of militant aesthetics is curated and rebroadcast as definitive proof of a fundamental truth: These people are not an alternative government; they are a national security threat and a cosmic joke rolled into one. The goal is to entrench in the wider public psyche, particularly among the cautious and the weary, a deep-seated fear that change equates to uncontrollable disorder.

On the international stage, this crafted image serves a similarly paradoxical purpose. It provides a passive, often unspoken, reassurance to external partners whose primary interest may be stability over democratic idealism. A polished, strategically savvy, and politically mature opposition presents a compelling case for switched allegiance. A movement that appears perpetually on the edge of bedlam, however, makes the strongman’s firm grip seem like the lesser of two evils. It allows foreign capitals to rationalise their continued engagement with the regime, nodding to concerns about human rights while privately sighing, “But look at the alternative.” The opposition, in this reading, becomes its own worst ambassador, confirming every patronising prejudice about chaotic African politics.

The tragedy of this makeover is its suffocating circularity. By performing the role of the unruly, incapable challenger—whether to mobilise a base with the adrenaline of confrontation or to satisfy an internal culture of perpetual rebellion—the movement actively undermines the very credibility required to become a ruling alternative. It becomes a self-sabotaging prophecy. They protest their exclusion from legitimate political space, yet their chosen mode of operation often justifies, in the eyes of many, their continued exclusion. They demand to be trusted with the nation’s future while presenting a public face of seemingly endemic impulsivity.

The tragedy of this makeover is its suffocating circularity. By performing the role of the unruly, incapable challenger—whether to mobilise a base with the adrenaline of confrontation or to satisfy an internal culture of perpetual rebellion—the movement actively undermines the very credibility required to become a ruling alternative. It becomes a self-sabotaging prophecy. They protest their exclusion from legitimate political space, yet their chosen mode of operation often justifies, in the eyes of many, their continued exclusion. They demand to be trusted with the nation’s future while presenting a public face of seemingly endemic impulsivity.Thus, the ultimate beneficiary of this villainous makeover is the dictatorship itself. The regime sits back as its challengers diligently apply the greasepaint of their own demonisation. Every misstep is a gift, every overreach a confirmation of the state’s indispensable role as the guardian of order. The political landscape becomes frozen in a perverse equilibrium where the strength of the incumbent is magnified by the carefully cultivated weakness of the principle challenger.

In the end, this is more than a tactical blunder; it is a profound failure of political imagination. It confuses the appearance of revolutionary fervour with the substance of revolutionary change. The old dictum warns that he who acts the part of a monster must not then weep when the world believes the performance. By embracing, for whatever reason, a public identity that aligns so perfectly with the regime’s caricature of dissent, the opposition risks forging the very chains that keep it bound to the margins, forever the raucous, unsettling spectacle in the wings, but never the steady hand on the lever of the state.

The Solo Act in a Chorus of Dissent: The Fragmentation of the Alternative

In the intricate and often fraught endeavour of building a challenge to an entrenched authority, unity is not merely a virtue; it is the fundamental currency of credibility. Yet, within Uganda’s political opposition, this currency appears chronically devalued. The pointed refusal to forge a consolidated front—exemplified by the rejection of a single, unified presidential candidate—reveals a landscape where the performance of individual defiance is often prized above the pragmatic arithmetic of collective power. The argument posits a stark rationale: such alliances are spurned precisely because they would impose a sobering discipline, a necessary consensus, that would stifle the very chaotic and emotionally charged style that has come to define, and perhaps confine, the struggle.

This preference for the solo act over the grand orchestra is rooted in a specific political culture. A unified front demands compromise, the sanding down of sharp personalistic edges for a common programme. It requires submitting to a shared strategy, often designed by committees and seasoned tacticians, rather than born from the spontaneous energy of a rally. For a movement built on the magnetic force of a central figure and the cathartic release of mass protest, such structures can feel like a cage. They curb the ability to make unilateral, dramatic gestures—the kind that generate immediate headlines and fervent supporter devotion—in favour of slower, more deliberate, and less telegenic coalition-building. The alleged “childish” style, with its impulsive energy and resistance to external moderation, is not considered a liability internally, but as an authentic, unfiltered expression of grievance that a bureaucratic alliance would inevitably dilute.

Consequently, the opposition landscape remains a fragmented tableau of smaller stages, each with its own star performer and devoted audience, rather than a single, formidable platform. This serves as a potent accelerant for the regime’s narrative. The dictatorship can effortlessly frame not one, but multiple opponents as unserious, their very inability to coalesce presented as prima facie evidence of their innate incapacity for national leadership. Why, the reasoning is offered to a weary public, should the country be entrusted to those who cannot even manage a simple agreement among themselves? The spectacle of internal squabbles and competing egos becomes a far more effective tool of state propaganda than any public relations officer, painting the entire project of change as inherently unstable.

Consequently, the opposition landscape remains a fragmented tableau of smaller stages, each with its own star performer and devoted audience, rather than a single, formidable platform. This serves as a potent accelerant for the regime’s narrative. The dictatorship can effortlessly frame not one, but multiple opponents as unserious, their very inability to coalesce presented as prima facie evidence of their innate incapacity for national leadership. Why, the reasoning is offered to a weary public, should the country be entrusted to those who cannot even manage a simple agreement among themselves? The spectacle of internal squabbles and competing egos becomes a far more effective tool of state propaganda than any public relations officer, painting the entire project of change as inherently unstable.The cost of this fragmentation is measured not in headlines, but in years. The argument highlights a stark toll: nearly a decade of alleged stagnation. While the energy of dissent is periodically spent in impressive, isolated eruptions, the sustained, patient work of constructing a nationwide alternative machinery—one that could withstand state pressure and present an undeniable electoral or moral force—is perpetually deferred. The struggle remains in a state of passionate adolescence, reacting to the regime’s moves with protest rather than proactively outmanoeuvring it with a superior, unified plan. Different factions, pursuing parallel and sometimes conflicting strategies, scatter their collective impact, allowing the regime to divide, contain, and exhaust them in turn.

Thus, the rejection of the alliance is more than a tactical disagreement; it is a philosophical commitment to a certain kind of politics. It is the choice of the symbolic, direct confrontation over the nuanced, collective long game. It is the belief that the purity of defiant identity is more valuable than the compromised potency of a shared front.

Yet, in this choice lies a profound and possibly devastating irony. The very style embraced as authentic and powerful may be the primary obstacle to its own success. For while a single twig breaks readily, a bundled faggot withstands the load. By remaining a collection of isolated twigs—each capable of a dramatic snap but incapable of bearing the weight of a nation’s hopes—the opposition not only postpones its own victory but actively constructs the display of weakness that the dictatorship depends upon to justify its perpetual, and seemingly unassailable, reign. The solo act receives an enthusiastic applause from its section of the gallery, but the house, itself, remains firmly under the control of the original, and only, management.

Yet, in this choice lies a profound and possibly devastating irony. The very style embraced as authentic and powerful may be the primary obstacle to its own success. For while a single twig breaks readily, a bundled faggot withstands the load. By remaining a collection of isolated twigs—each capable of a dramatic snap but incapable of bearing the weight of a nation’s hopes—the opposition not only postpones its own victory but actively constructs the display of weakness that the dictatorship depends upon to justify its perpetual, and seemingly unassailable, reign. The solo act receives an enthusiastic applause from its section of the gallery, but the house, itself, remains firmly under the control of the original, and only, management.The Harvest of Defiance: The Inescapable Arithmetic of Political Choice

In the fraught and unforgiving arena of Ugandan politics, where every declaration is a gambit and every silence a calculation, there exists a law as immutable as the turning of the seasons: the law of consequence. It is a principle that hovers over the ambitions of challengers like a stern, unblinking spectre. The admonition once offered by Dr. Kizza Besigye—that to spurn counsel is to inevitably embrace the outcomes of that rejection—is not merely a witty aphorism; it is the cold, operational logic of political cause and effect. Its biblical corollary, ‘you reap what you sow,’ translates from the spiritual to the starkly material here, framing the nation’s struggle as a vast, unyielding field where the seeds of today’s strategies determine the harvest of tomorrow’s reality.

This warning speaks directly to the perils of a political culture that mistakes unwavering stubbornness for principled resolve. To dismiss seasoned advice—whether on coalition-building, strategic moderation, or long-term grassroots organisation—is not an act of revolutionary purity, but a conscious decision to plant seeds of isolation, fragmentation, and reactionary tactics. The field does not discriminate between seeds sown in righteous anger or those planted in careful deliberation; it merely yields according to the nature of the crop. A harvest of bitter frustration and stunted growth should surprise no one when the seeds were those of perpetual confrontation without an accompanying plan for cultivation.

For the citizenry, this law manifests with a tangible, often brutal, clarity. The promised fruit of liberation—security, accountability, prosperity—remains perpetually out of reach, a mirage on the horizon, because the labour and the seeds invested have been repeatedly directed elsewhere. Energy is sown into spectacular, single-season protests that wilt under the state’s harsh sun, rather than into the deep-rooted, patient growth of institutional alternatives. The yield, consequently, is not nourishment, but a recurring cycle of hope and exhaustion. The people are left to partake of a meagre harvest, wondering why the soil of their nation, so rich with potential, yields such a scant and disappointing crop under the stewardship of those promising abundance.

For the citizenry, this law manifests with a tangible, often brutal, clarity. The promised fruit of liberation—security, accountability, prosperity—remains perpetually out of reach, a mirage on the horizon, because the labour and the seeds invested have been repeatedly directed elsewhere. Energy is sown into spectacular, single-season protests that wilt under the state’s harsh sun, rather than into the deep-rooted, patient growth of institutional alternatives. The yield, consequently, is not nourishment, but a recurring cycle of hope and exhaustion. The people are left to partake of a meagre harvest, wondering why the soil of their nation, so rich with potential, yields such a scant and disappointing crop under the stewardship of those promising abundance.The regime, in its enduring fortitude, understands this arithmetic intimately. It has, over decades, sown its own seeds with meticulous, amoral care: the wind-blown seeds of fear, the deep-rooted seeds of patronage, the genetically modified seeds of a security apparatus that chokes out competing growth. It reaps its own harvest accordingly: a landscape where its own power grows perennial and hardy, while opposition crops struggle to sprout in the shade. It watches as its challengers, in their rejection of certain kinds of difficult, patient labour, choose seeds that cannot thrive in this engineered ecosystem, guaranteeing another season of its own dominion.

Thus, the adage stands as a monumental rebuke to the politics of perpetual gesture over grounded strategy. It is a reminder that in the face of a regime that calculates with the patience of decades, the rejection of strategic advice is not a badge of honour but a pre-written prescription for failure. The consequences—continued marginalisation, public disillusionment, the strengthening of the dictator’s hand—are not acts of fate, but the direct produce of earlier, deliberate choices.

For the wheel of consequence turns on its own axle, indifferent to the cries of those it crushes. In the end, the field yields what is planted, not what is promised. A movement that sows the wind of chaotic, uncontained defiance must, by nature’s own remorseless law, brace itself to reap the whirlwind of its own inconsequence, leaving the granaries of power full, and the people’s baskets achingly empty.

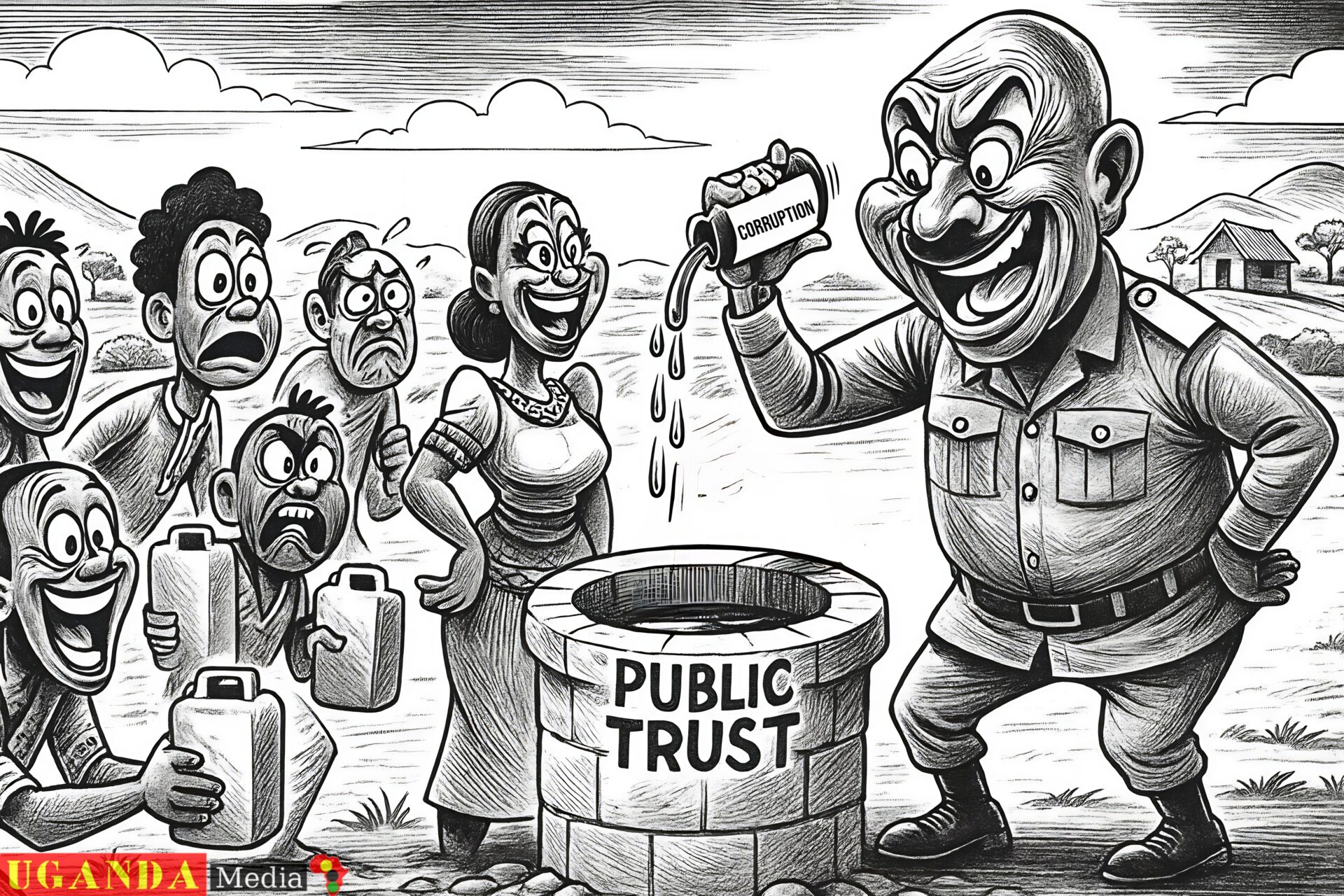

The Alchemy of Empty Promises: When Political Hope is Commodified

In the bustling, hopeful, and often desperate ecosystem of Ugandan opposition politics, the most potent currency is not just votes, but faith. The staggering narrative of Sir Mathias Walukaga—his life’s assets liquefied into a 300 million shilling party card—transcends mere financial loss. It represents the ultimate alchemical transaction of modern dissent: the conversion of a citizen’s tangible, earthly wealth into the promised, but perpetually intangible, gold of political liberation. His cry is not one of simple disappointment, but the raw sound of a dream devalued into a worthless voucher, a golden ticket that granted entry only to a barren waiting room.

This transaction reveals the internal machinery of a movement in a devastating light. The hefty financial contribution, whether framed as a nomination fee, a “support the struggle” levy, or an investment in one’s own candidacy, functions as a perverse rite of passage. It is a test of loyalty measured not in courage or hours of mobilisation, but in banknotes. For the aspiring candidate, it feels like purchasing a share in the future itself. For the party structure, it becomes a vital, if ethically nebulous, revenue stream—the “struggle money” that oils the gears of rallies, transport, and publicity. Walukaga’s life savings did not simply vanish; they were absorbed into the daily operational budget of a perpetual campaign that has yet to breach the walls of State House.

This transaction reveals the internal machinery of a movement in a devastating light. The hefty financial contribution, whether framed as a nomination fee, a “support the struggle” levy, or an investment in one’s own candidacy, functions as a perverse rite of passage. It is a test of loyalty measured not in courage or hours of mobilisation, but in banknotes. For the aspiring candidate, it feels like purchasing a share in the future itself. For the party structure, it becomes a vital, if ethically nebulous, revenue stream—the “struggle money” that oils the gears of rallies, transport, and publicity. Walukaga’s life savings did not simply vanish; they were absorbed into the daily operational budget of a perpetual campaign that has yet to breach the walls of State House.The tragedy is layered with a piercing irony. Walukaga, and others like him, are not passive victims of a scam. They are true believers. They bought into a narrative of imminent change so completely they were willing to monetise their entire existence for it. The promised return was not just a parliamentary seat, but a stake in a new Uganda. The advice from the Secretary-General—to return to music and organise a concert—is therefore not just callous, but a profound philosophical betrayal. It reduces a profound political sacrifice to the level of a failed fundraising gig, acknowledging the monetary value while utterly dismissing the invested hope. It tells him the movement has consumed his seed but cannot be bothered to tend the field where it was sown.

This dynamic cultivates a devastating harvest. For every Walukaga, there are hundreds, perhaps thousands, of smaller investors—the shopkeeper who contributed a million, the teacher who gave two hundred thousand—all feeling a sense of ownership in a project that appears to have no accountable board of directors. Their collective investment purchases posters, lorries, and banners, but not, it seems, a winning strategy. When the electoral cycle concludes with meagre gains, the resultant bitterness is not just political; it is deeply personal and financial. The loss of a life’s work breeds a resentment more enduring than any policy disagreement. It turns ardent supporters into creditors of a bankrupt dream.

Furthermore, this system of internal finance becomes a mirror of the very patronage politics the movement claims to oppose. It creates a hierarchy where access and candidacy can appear contingent on financial capacity rather than pure merit or grassroots appeal, favouring the well-heeled convert over the organic, community-rooted leader. The struggle against a billionaire dictatorship risks becoming a playground for the aspirational upper-middle class, with the poor footing the bill through their meagre contributions and bodily risk.

Furthermore, this system of internal finance becomes a mirror of the very patronage politics the movement claims to oppose. It creates a hierarchy where access and candidacy can appear contingent on financial capacity rather than pure merit or grassroots appeal, favouring the well-heeled convert over the organic, community-rooted leader. The struggle against a billionaire dictatorship risks becoming a playground for the aspirational upper-middle class, with the poor footing the bill through their meagre contributions and bodily risk.Ultimately, Walukaga’s 300 million shillings is a stark measure of the credibility gap. It is the catastrophic difference between the price of hope and its market value. For the tallest castle built upon a foundation of sand will command the most spectacular ruin. He was sold a vision of a castle—his seat in Parliament, his role in liberation—and he paid for its blueprint in full. But the foundation, the unglamorous, patient, unified, and strategically sound groundwork necessary to support such a structure, remained unpoured. Now, he holds an expensive, beautifully rendered document, standing knee-deep in the shifting grains of political reality, watching the tide come in, while the architects of his dream are inexplicably preoccupied elsewhere, already sketching new blueprints for the next eager investor.

The Architecture of Inaccessibility: When the Ladder of Grievance is Pulled Up

In the sprawling, bustling polity of dissent, where hope is the primary fuel and grievance the common currency, a silent, structural fault line runs through the very idea of the movement. It is the chasm between the promise of a people’s struggle and the stark reality of its inaccessible pinnacle. The plight of Sir Mathias Walukaga, his frantic calls met with a void of silence, is not an isolated customer service failure; it is a parable of a hierarchy that has solidified even as it preaches horizontality. The leaders—the ‘People’s President,’ the eloquent spokesman—retreat behind a glazed perimeter, becoming majestic, voiceless statues on a pedestal, while the very people who form the pedestal’s foundation weep at its base.

This inaccessibility is multifaceted. It is physical, enacted through layers of security, handlers, and the insulating bubble of busy schedules that separate the figurehead from the foot soldier. It is technological, where the personal telephone number—once a symbol of revolutionary approachability—becomes a guarded secret, its ringing tone a privilege afforded only to a curated inner circle. The leader becomes a broadcast node, transmitting messages to the masses, but no longer a reception point for the raw, unedited feedback from them. The communication is a monologue, delivered from a raised platform, not a dialogue in the back of a pickup truck.

The transformation is both tragic and predictable. As the movement gains scale and its principal figures acquire a state-like stature in response to state-like persecution, they unconsciously begin to mimic the very structures they contest. The regime’s President is famously insulated; now the ‘People’s President’ becomes similarly unreachable, albeit for different, arguably security-related reasons. The consequence, however, is a mirrored dysfunction: a leadership that cannot hear the true pitch of its followers’ despair. The circus masters, orchestrating ever-grander shows of defiance, grow deaf to the backstage whispers of broken props and injured clowns. They hear the roar of the crowd, but not the whimper of the individual.

This breeds a profound and destabilising alienation. For the ordinary member who has sacrificed savings, safety, or social standing, the leader is not just a strategist but a vessel for their aspirations. That leader’s perceived accessibility is the proof that this struggle is different, that it is organic and accountable. When that conduit seizes up, the sacrifice feels transactional and hollow. The movement risks becoming a vehicle for the ambitions and security of its top tier, while the rank and file are reduced to a source of crowd volume and financial contribution—a human resource to be mobilised, not a community to be listened to.

Thus, the silence on the other end of Walukaga’s call is more than a personal snub; it is a systemic echo. It signals a movement where grievance flows upward only as far as the middle management, where the ultimate architects are shielded from the crumbling bricks. The tragedy is that this insulation, often justified by genuine security concerns, ultimately undermines security itself. It frays the bonds of trust that are the only true armour against infiltration, disillusionment, and collapse.

For those who build their house upon the mountain cannot then complain of the valley’s chill. By ascending to a remote, fortified political summit, the leadership inadvertently creates the very distance that allows the regime to mock their ‘people-centred’ claims. The people are left in the valley, shouting their woes upwards, their voices thinned by the altitude, while the object of their devotion is silhouetted against the sky, gesturing broadly at a future he can no longer hear them asking for. The ladder of grievance has been pulled up behind him, leaving the faithful to wonder if they are supporters in a common cause, or simply an audience for a solitary, and increasingly detached, performance.

The Calculus of Sacrifice: When the Struggle Consumes Its Own

In the intricate ledger of political dissent, where the columns list assets of hope and liabilities of risk, the transaction between Sir Mathias Walukaga and the Secretary-General represents a chilling final entry. It is the moment the abstract, all-consuming entity known as “the struggle” is invoked not as a rallying cry, but as a forensic accounting term, a black hole of finance where personal futures vanish without a trace. The advice to return to music and organise a concert is not merely impractical; it is a profound philosophical surrender, a declaration that the political project has no answer for the individual ruin it catalyses.

This exchange lays bare a brutal hierarchy of sacrifice. Walukaga offered a concrete, total offering: his property, his credit, his political ambition, distilled into 300 million shillings. The movement’s apparatus, in return, consumed it as operational fuel—petrol for generators at rallies, printing costs for posters, per diems for coordinators. His life’s capital was converted into the ephemeral, daily running costs of a permanent campaign. The Secretary-General’s response confirms the transaction’s true nature: the money is not an investment held in trust, but an expended resource. The struggle, like a furnace, requires constant feeding, and Walukaga willingly became its fuel. His dream was not deferred; it was incinerated to keep the engine warm.

The suggestion of a concert as redress is thus a masterpiece of tragic irony. It reduces a profound political grievance—the commodification of hope—to a mere logistical problem of revenue generation. It pushes the responsibility for reparations back onto the victim, framing him as a freelance entrepreneur of his own misfortune. The subtext is damning: Your role for us was as a donor; now your role in recovery is as a fundraiser. The movement giveth, and the movement taketh away. He is ejected from the political sphere, where he sought a seat at the table, and re-cast into the cultural sphere, where he is told to sing for his supper and hopefully recoup his losses from the very community already impoverished by hope.

The suggestion of a concert as redress is thus a masterpiece of tragic irony. It reduces a profound political grievance—the commodification of hope—to a mere logistical problem of revenue generation. It pushes the responsibility for reparations back onto the victim, framing him as a freelance entrepreneur of his own misfortune. The subtext is damning: Your role for us was as a donor; now your role in recovery is as a fundraiser. The movement giveth, and the movement taketh away. He is ejected from the political sphere, where he sought a seat at the table, and re-cast into the cultural sphere, where he is told to sing for his supper and hopefully recoup his losses from the very community already impoverished by hope.This moment illuminates the dangerous abstraction at the heart of the endeavour. “The struggle” becomes a sovereign entity, a higher cause to which all earthly possessions must be forfeit. It justifies any internal appropriation, any broken promise, because the ultimate, celestial goal is said to outweigh all temporal losses. This mirrors, in a perverse way, the very state ideology it opposes, where national security and developmental progress are invoked to excuse any present-day extraction or suffering. The opposition risks creating its own miniature shadow-state, with its own non-negotiable taxes and its own dismissive bureaucracy for handling complaints.

For the wider supporter base, this is a cautionary tale of devastating clarity. It delineates the boundary between supporter and usable resource. It whispers that your sacrifice, however total, is ultimately a consumable, not an investment with guaranteed returns. The personal connection to the leadership, the feeling of shared purpose, evaporates in the face of such transactional coldness. The movement’s humanity is called into question when it cannot muster a humane response to a tragedy it facilitated.

Therefore, one must be cautious of the cause that is forever hungry, yet never provides a meal. Walukaga fed the struggle his entire harvest, and when he returned, starving, to the granary, he was handed a guitar and told to serenade the empty silo. The leadership, having consumed the seed corn of his future, now admires the hollow melody of his ruin, while the furnace of their ambition roars on, demanding still more fuel, and offering, in return, only the cold comfort of its relentless, all-justifying flame.

Therefore, one must be cautious of the cause that is forever hungry, yet never provides a meal. Walukaga fed the struggle his entire harvest, and when he returned, starving, to the granary, he was handed a guitar and told to serenade the empty silo. The leadership, having consumed the seed corn of his future, now admires the hollow melody of his ruin, while the furnace of their ambition roars on, demanding still more fuel, and offering, in return, only the cold comfort of its relentless, all-justifying flame.The Ladder and the Roots: An Ascent That Invites Inquiry

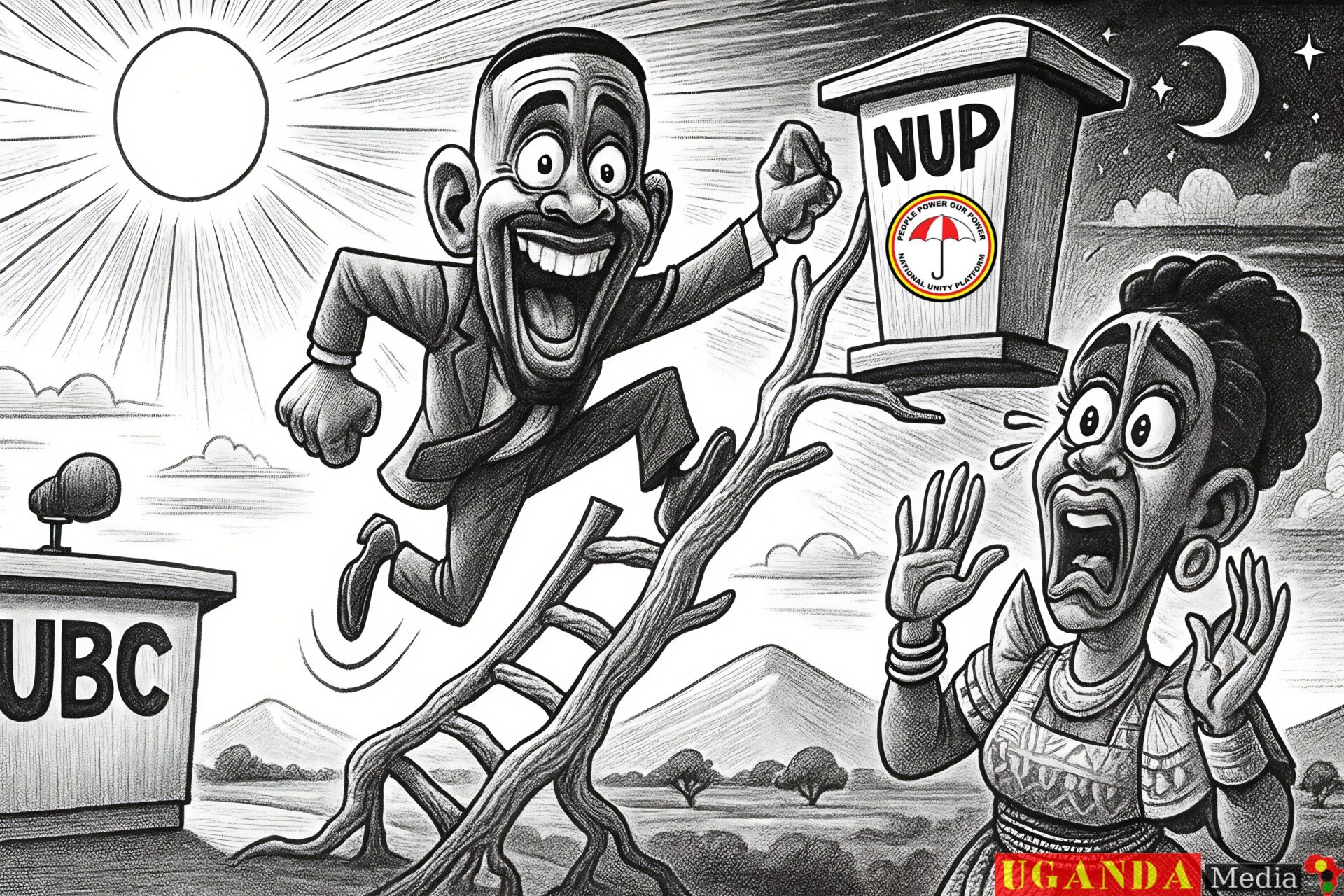

In the intricate theatre of Ugandan dissident politics, where every biography is scrutinised for authenticity and every asset weighed for its origin story, the trajectory of a figure like Joel Ssenyonyi presents a compelling sub-plot of ambiguous optics. His journey—from a familiar voice on the state broadcaster’s evening news bulletin, introduced to the nation as Joel Bisekezi, to a principal spokesman for the chief opposition party, now reportedly residing in a mansion—is a narrative arc that fuels intense speculation. This rapid ascent, set against a backdrop of whispered familial connections to the very epicentre of power he now critiques, poses a persistent, prickling question: is this the path of a true rebel, or the calculated repositioning of a splendidly placed player?

The transformation is stark. The government-owned Uganda Broadcasting Corporation (UBC) in 2006 was, and remains, an arm of the state’s narrative machinery. To read the news from that desk was to be the calibrated, trusted voice of the established order, a daily reaffirmation of its reality. To pivot from that role to becoming the defiant, sharp-tongued counter-voice of the National Unity Platform is not merely a change of employer; it is a profound reinvention of public identity. Such a leap inevitably invites scrutiny. In a society where political affiliation often feels hereditary and where crossing the deep chasm between regime and opposition is fraught with existential risk, a seamless transition is viewed with a mixture of awe and deep suspicion.

The transformation is stark. The government-owned Uganda Broadcasting Corporation (UBC) in 2006 was, and remains, an arm of the state’s narrative machinery. To read the news from that desk was to be the calibrated, trusted voice of the established order, a daily reaffirmation of its reality. To pivot from that role to becoming the defiant, sharp-tongued counter-voice of the National Unity Platform is not merely a change of employer; it is a profound reinvention of public identity. Such a leap inevitably invites scrutiny. In a society where political affiliation often feels hereditary and where crossing the deep chasm between regime and opposition is fraught with existential risk, a seamless transition is viewed with a mixture of awe and deep suspicion.The whispered lineage—a hinted familial tether to the dictator himself—adds a layer of Shakespearean complexity. If true, it reframes his opposition not as that of an outsider storming the gates, but as a drama of intimate insurrection. It fosters a narrative, beloved by regime propagandists, that the opposition is not a people’s movement but a family feud, a staged theatre of controlled dissent where even the critics emerge from the inner sanctum. The symbolic potency of this is immense: the mansion, then, is not read as a reward for journalistic or political success, but potentially as an inheritance of privilege that persists regardless of political costume. It allows a damaging question to hang in the air: can one truly dismantle a house when one’s own keys might still fit the back door?

This places Ssenyonyi in a uniquely paradoxical position. His effectiveness as a spokesman is undeniable, his articulation of grievance resonating with a wide audience. Yet, this unresolved backstory perpetually shadows his personal narrative. For the sceptical supporter, his ascent feels almost too smooth, his access too prominent, his security too assured in a landscape where other dissidents face untrammelled harassment. He becomes a living Rorschach test: to the faithful, his is a story of enlightened defection, proof that even those who saw the machine from within were compelled to reject it; to the cynical, he is the ultimate embedded narrative, a safety valve of credible dissent whose very presence subtly suggests the regime’s enduring, inescapable reach.

Thus, his rise underscores a central tension within the opposition’s struggle: the desperate need for polished, credible faces to articulate its case, set against the corrosive power of whispers that undermine those faces’ foundational authenticity. It speaks to a environment where trust is the scarcest commodity, and every personal history is a battleground for interpretation.

For a man cannot climb a new ladder while forever suspected of holding the deed to the old one. Ssenyonyi’s journey, impressive in its pace and scale, remains shadowed by the indelible ink of his past and the opaqueness of his connections. Whether he is a master of his own narrative or a piece in a larger, more cynical game, his story serves as a potent metaphor for an opposition movement forever grappling with the ghosts of the established order it seeks to replace, wondering if some among them are rebels, or simply well-cast understudies in a play whose final act the director has no intention of changing.

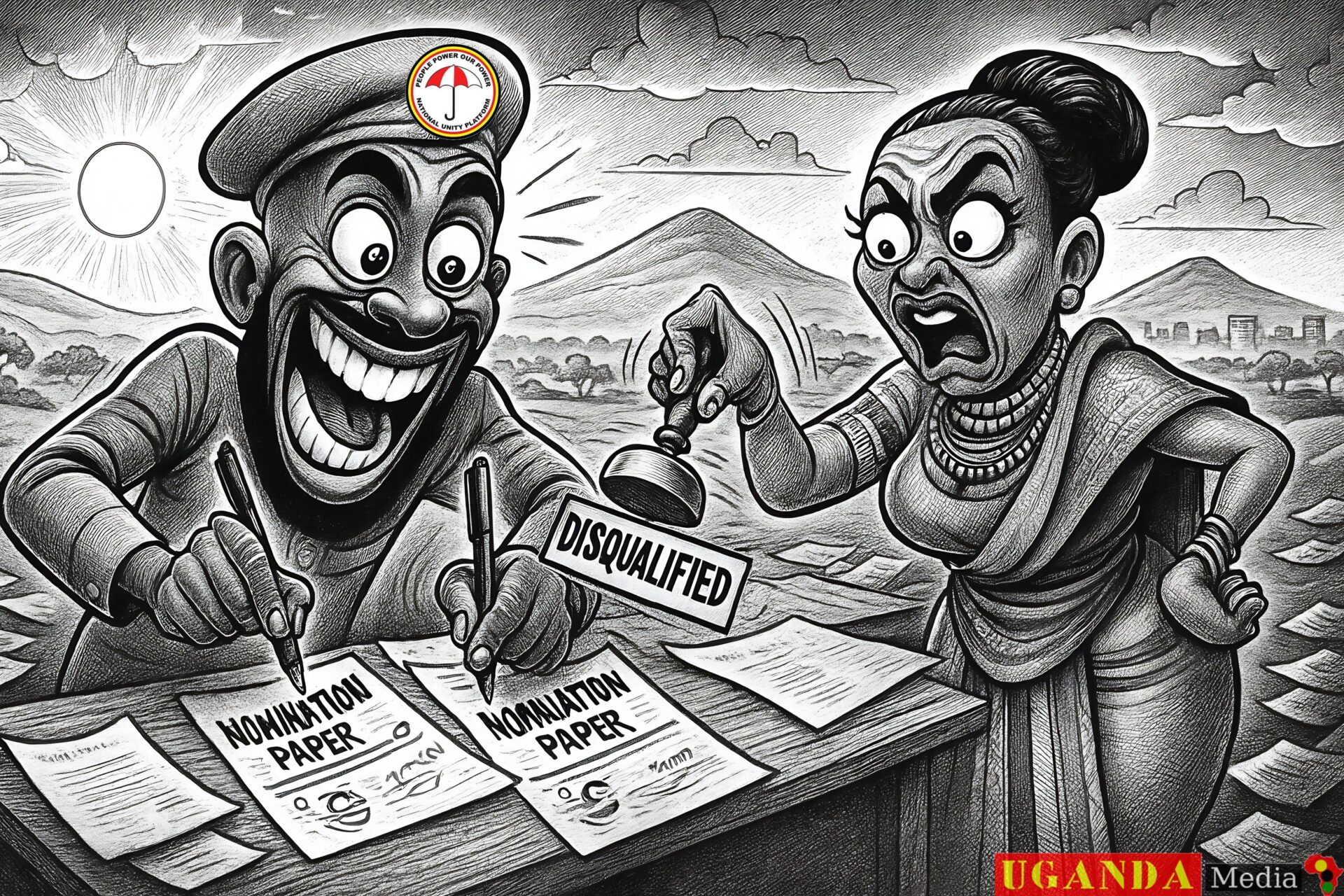

For a man cannot climb a new ladder while forever suspected of holding the deed to the old one. Ssenyonyi’s journey, impressive in its pace and scale, remains shadowed by the indelible ink of his past and the opaqueness of his connections. Whether he is a master of his own narrative or a piece in a larger, more cynical game, his story serves as a potent metaphor for an opposition movement forever grappling with the ghosts of the established order it seeks to replace, wondering if some among them are rebels, or simply well-cast understudies in a play whose final act the director has no intention of changing.The Farce of Incompetence: When the Revolution is Undermined by its own Paperwork

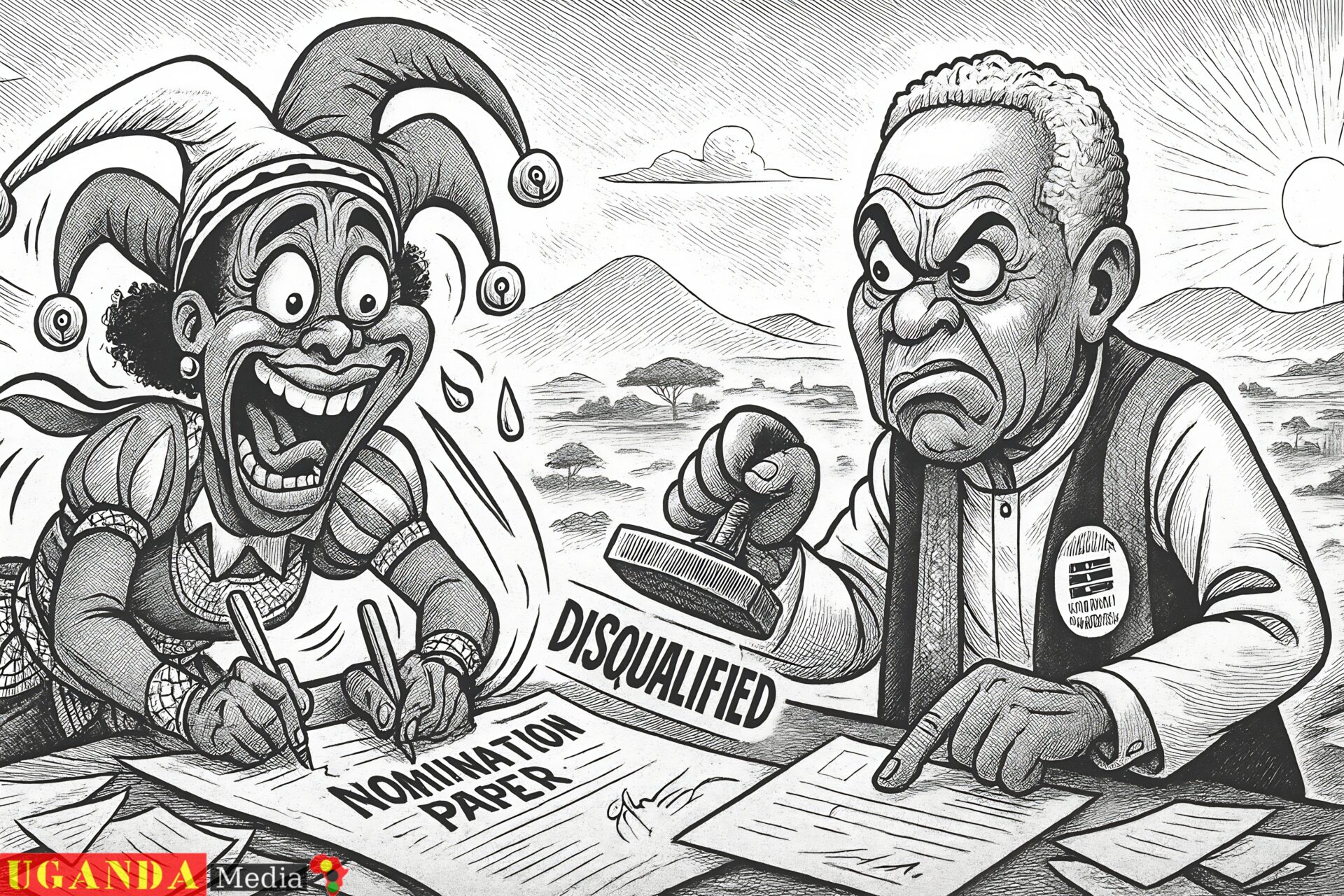

In the high-stakes, unforgiving arena of challenging an entrenched dictatorship, where every move is scrutinised, and every slip magnified, credibility is the most fragile of currencies. It is painstakingly built through demonstrations of courage, strategic acumen, and, fundamentally, a basic operational competence that suggests fitness to govern. The revelation of a blunder such as Tadeo Niwamanya’s—the alleged double-signing on a candidate’s nomination papers, leading to a wholly avoidable disqualification—is therefore not a minor clerical error. It is a catastrophic failure of political theatre, a moment where the aspiring government-in-waiting peels back the curtain to reveal not a war room of meticulous strategists, but a chaotic backstage where the most elementary scripts are bungled.

This is the domain of the administrative jester. While the leadership speaks in grand, soaring rhetoric of liberation and new dawns, the machinery at ground level appears to be held together with blu-tack and hopeful guesswork. The nomination process, governed by the regime’s own exacting and often weaponised electoral laws, is a first and fundamental test of a party’s seriousness. It is a bureaucratic gauntlet where the state lies in wait for the slightest pretext to disqualify. To stumble at this hurdle, not through nefarious state machination but through self-inflicted, pedestrian carelessness, is to hand one’s opponent a gift of immeasurable propaganda value. It transforms a political competitor into a figure of ridicule.

This is the domain of the administrative jester. While the leadership speaks in grand, soaring rhetoric of liberation and new dawns, the machinery at ground level appears to be held together with blu-tack and hopeful guesswork. The nomination process, governed by the regime’s own exacting and often weaponised electoral laws, is a first and fundamental test of a party’s seriousness. It is a bureaucratic gauntlet where the state lies in wait for the slightest pretext to disqualify. To stumble at this hurdle, not through nefarious state machination but through self-inflicted, pedestrian carelessness, is to hand one’s opponent a gift of immeasurable propaganda value. It transforms a political competitor into a figure of ridicule.The impact of such a farce is multifaceted. For the disqualified candidate and their supporters in, say, Isingiro District, it is a betrayal. Their energy, loyalty, and hope are rendered null by a party official who could not execute the simplest of tasks. It tells them their political destiny is worth less than the time it takes to verify a signature. For the neutral observer, it invites a devastating comparison. The National Resistance Movement machinery, for all its other flaws, rarely makes such unforced errors in its own electoral operations. It is a leviathan of bureaucratic control, its paperwork impeccably in order, its processes ruthlessly efficient in securing its own outcomes. The opposition, by contrast, can appear as a spirited but shambolic protest group, incapable of managing the basic admin of its own ambition.

This breeds a profound and damaging narrative: that the opposition is not merely out-gunned, but out-classed. The dictator’s long reign has institutionalised a certain cold, procedural efficiency in maintaining power. When the alternative cannot demonstrate a superior, or even a basic, competence in the mechanics of politics, it validates the regime’s most potent, condescending claim: “These are just emotional children playing at politics; you cannot trust them with a county budget, let alone the national treasury.” The revolution is not televised; it is tripped up at the returning officer’s desk by its own shoelaces.

This breeds a profound and damaging narrative: that the opposition is not merely out-gunned, but out-classed. The dictator’s long reign has institutionalised a certain cold, procedural efficiency in maintaining power. When the alternative cannot demonstrate a superior, or even a basic, competence in the mechanics of politics, it validates the regime’s most potent, condescending claim: “These are just emotional children playing at politics; you cannot trust them with a county budget, let alone the national treasury.” The revolution is not televised; it is tripped up at the returning officer’s desk by its own shoelaces.Thus, the jester’s error is a symbolic poison. It suggests a culture where passion is valued over precision, where loyalty may be placed above competence, and where the gravity of the mission is insulted by a slapdash approach to its execution. It makes the struggle seem not just difficult, but unserious.

For the most formidable fortress can be breached, but never by an army that keeps forgetting the password. Each Niwamanya-level blunder is a forgotten password, a squad of would-be liberators left locked outside, hammering on the gate in frustration while the garrison within shares a hearty, contemptuous laugh. It convinces no new allies, it demoralises the faithful, and it allows the entrenched regime to lean back, not even needing to deploy its heavy weaponry, as the challenge to its authority evaporates in a cloud of its own administrative ineptitude and farcical disarray.

For the most formidable fortress can be breached, but never by an army that keeps forgetting the password. Each Niwamanya-level blunder is a forgotten password, a squad of would-be liberators left locked outside, hammering on the gate in frustration while the garrison within shares a hearty, contemptuous laugh. It convinces no new allies, it demoralises the faithful, and it allows the entrenched regime to lean back, not even needing to deploy its heavy weaponry, as the challenge to its authority evaporates in a cloud of its own administrative ineptitude and farcical disarray.The Poisoning of the Pulpit: When Political Frustration Erodes Sacred Ground

In the delicate ecosystem of Ugandan public life, where faith provides both sanctuary and a powerful moral compass, the boundaries between the spiritual and political arenas are treated with a cautious, often unspoken reverence. The reported reaction to being denied access to the Rubaga Cathedral pulpit—a call for ‘foot soldiers’ to confront Archbishop Paul Ssemogerere—represents more than a tactical misstep. It is a profound failure of political discernment, a moment where raw frustration actively dismantles the very pillars of moral authority and public sympathy upon which a credible challenge to authority must be built. The image conjured is not of a righteous petitioner, but of a force seeking to lay siege to a sanctuary, swapping the solemn for the thuggish with a single, ill-considered phrase.

The cathedral, in the social fabric of the nation, exists as territory of a different order. It is not merely another rally ground or community hall. It is a symbol of spiritual continuity that predates and is meant to outlast any political regime or movement. To demand its platform as a right, and to respond with threats when it is withheld, commits a dual offence. Firstly, it disrespects the autonomy of a foundational institution, treating the Church not as a body with its own independent judgement, but as a mere venue to be commandeered. Secondly, and more catastrophically, it inverts the desired moral narrative. Instead of portraying the opposition as persecuted seekers of justice appealing to a higher moral law, it risks painting them as aggressors willing to coerce the clergy, thereby placing themselves on the wrong side of the very moral authority they seek to claim.

The cathedral, in the social fabric of the nation, exists as territory of a different order. It is not merely another rally ground or community hall. It is a symbol of spiritual continuity that predates and is meant to outlast any political regime or movement. To demand its platform as a right, and to respond with threats when it is withheld, commits a dual offence. Firstly, it disrespects the autonomy of a foundational institution, treating the Church not as a body with its own independent judgement, but as a mere venue to be commandeered. Secondly, and more catastrophically, it inverts the desired moral narrative. Instead of portraying the opposition as persecuted seekers of justice appealing to a higher moral law, it risks painting them as aggressors willing to coerce the clergy, thereby placing themselves on the wrong side of the very moral authority they seek to claim.This plays directly into the hands of the dictatorship’s enduring narrative. The regime, whose origins are deeply entwined with a historical liberation theology but whose practices have long diverged, is gifted a potent public relations coup. It can now posture, however cynically, as the guardian of institutional order and religious respect. The state’s own frequent overreach is momentarily obscured by the spectacle of its challengers appearing to threaten a respected archbishop. The message broadcast is precisely the one the opposition can least afford: that their movement is not one of principled elevation, but of uncontrollable volatility, one that cannot tell a pulpit from a podium and views all spaces as territories to be captured through pressure or intimidation.

For the average faithful Ugandan, whose political hopes may be intertwined with deep religious conviction, such an incident creates a distressing cognitive dissonance. It forces a choice where none should exist. It alienates the very constituency that forms the backbone of societal stability—those who seek change but within a framework of respected tradition and moral order. The movement appears to be attacking one of the few remaining centres of perceived neutrality and conscience, burning a bridge to the wider community in a blaze of impulsive fury.

Ultimately, this confrontation is a lesson in the intangible currencies of power. Political strength derives not only from crowds and slogans but from perceived legitimacy, restraint, and the moral high ground. To lose that high ground over access to a microphone, however symbolically significant, is a catastrophic trade.

For he who poisons the well in a fit of thirst cannot then complain of the drought that follows. By lashing out at the archbishop, the reaction poisoned a vital well of public sympathy and moral credibility. The momentary thirst for a platform, however justified the grievance may have felt, risks triggering a longer, deeper drought of trust and respect, leaving the political landscape even more arid and unforgiving for those who genuinely seek to cultivate a new future. It demonstrates a tragic confusion of targets, where the energy required to challenge a fortified state is instead expended on breaching the walls of a cathedral, achieving nothing but the echoing scandal of one’s own footsteps in a hollow, desecrated space.

For he who poisons the well in a fit of thirst cannot then complain of the drought that follows. By lashing out at the archbishop, the reaction poisoned a vital well of public sympathy and moral credibility. The momentary thirst for a platform, however justified the grievance may have felt, risks triggering a longer, deeper drought of trust and respect, leaving the political landscape even more arid and unforgiving for those who genuinely seek to cultivate a new future. It demonstrates a tragic confusion of targets, where the energy required to challenge a fortified state is instead expended on breaching the walls of a cathedral, achieving nothing but the echoing scandal of one’s own footsteps in a hollow, desecrated space.The Foundational Fracture: Re-examining the Genesis of a Rebellion

To navigate the present contours of Ugandan politics is to inevitably stumble into the ghost-laden cavern of 1980. It is the nation’s original sin, the disputed genesis of the current order, a historical detour that is, in fact, the main road. The perspective offered here is a formidable challenge to entrenched orthodoxy: it posits the 1980 general election not as the blatant theft that justified a bush war, but as the last credible expression of the national will before a new, more enduring system of control was forged in the forests of Luwero. From this vantage point, the much-cited claim of widespread, fraudulent ‘unopposed’ declarations for the Uganda Peoples Congress is presented not as fact, but as the essential, pre-manufactured pretext for a conflict already decided upon.

The argument rests on a foundation of observable absence. After the turmoil of the Amin years, the 1980 poll was an attempt to restore parliamentary governance. While flawed and contested—as many post-conflict elections are—its outcome was, this view holds, broadly reflective of the political landscape. The critical evidentiary hole is highlighted: the alleged malpractice of ‘unopposed’ declarations was never tested in a court of law. Neither the Democratic Party, which protested loudly, nor the Uganda Patriotic Movement of a young Yoweri Museveni, pursued legal redress for what they claimed was a wholesale subversion of democracy. This lacuna is presented not as an oversight, but as a telling silence. Why not exhaust the constitutional avenues if the fraud was so blatant and documentable? The suggestion is that the legal route was never the intended one.