The Great Ugandan Disconnect: When Manifestos Meet the Dusty Campaign Trail

In the vibrant, often chaotic, theatre of Ugandan politics, a new act is beginning. As the 2026 general elections loom, presidential hopefuls are crisscrossing the nation, from the bustling streets of Kampala to the remote villages of Karamoja, selling visions of a brighter future. Their weapon of choice? The manifesto—a voluminous document promising everything from economic transformation to universal prosperity. But in a nation where the ruling party has been in power for nearly two generations, and where the campaign trail is littered with the broken promises of elections past, a pressing question emerges: Are these manifestos a genuine blueprint for development, or merely elaborate works of fiction?

As Uganda stands at a critical juncture ahead of the 2026 general elections, a profound disconnect defines its political landscape. This in-depth analysis dissects the chasm between the glossy, voluminous manifestos of parties like the National Resistance Movement (NRM), National Unity Platform (NUP), and Forum for Democratic Change (FDC), and the gritty realities of a campaign trail marked by police intimidation, vote-buying, and empty spectacle. We examine the NRM’s strategy of “protecting the gains” through the politics of survivalism, the opposition’s detailed yet trust-deficient policy pitches, and the fundamental crisis of leadership and accountability that renders many pledges meaningless. From the bloated state bureaucracy and the ghost of infrastructure promises like the Standard Gauge Railway to the suffocation of civic space and the commercialisation of the vote itself, this exploration questions whether 2026 will be a genuine policy debate or a referendum on the very soul of a nation trapped between a rock and a hard place. Join us as we unravel the threads of promise and performance to understand the true battle for Uganda’s future. leftist in writing:

Twenty Key Insights into Uganda’s Political Crossroads

The Pot that Does Not Cook: Dissecting the NRM’s “Reincarnated” Manifesto

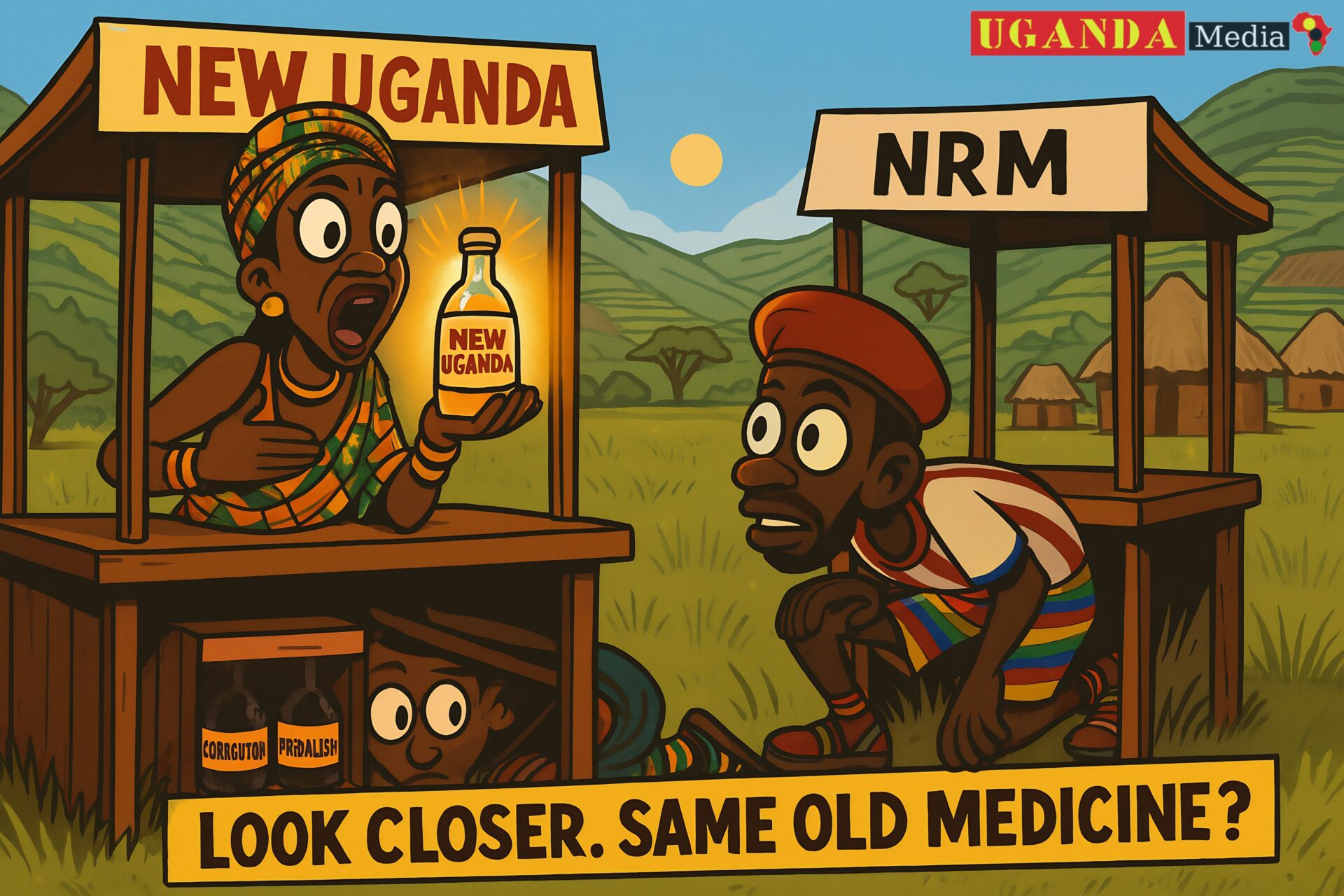

In the vibrant tapestry of Ugandan politics, a familiar scene unfolds with each election cycle. The National Resistance Movement (NRM) unveils its latest manifesto—a weighty, carefully branded document promising a future transformed. This season, it is titled “Protecting the Gains.” Yet, to a growing number of Ugandans, from the intellectual in Kamwokya to the farmer in Kumi, this new pledge bears a hauntingly familiar face. It is what critics aptly term a “reincarnated” manifesto: the same old spirit of past promises, merely inhabiting a new body with a fresh cover.

This is not merely political opposition rhetoric; it is a diagnosis of a political culture that has prioritised presentation over profound change. The phenomenon can be understood through several key facets:

1. The Art of Political Repackaging

The core criticism lies in the perception that the NRM, after nearly four decades in power, is not proposing a new journey but is instead selling a new map for the same well-trodden path. The 185-page “Protecting the Gains” document is seen not as a blueprint for a new house, but as a fresh coat of paint on a structure whose foundations many feel are cracking. The central pillars—peace, security, infrastructure, and wealth creation—are not new. They are the same pillars that have been presented, in various configurations, for multiple election cycles. The argument is that the party has resorted to what one might call “political synonymy”—swapping phrases like “Securing the Future” for “Protecting the Gains” to create an illusion of progress and renewal, while the substantive agenda remains static.2. “Old Wine in New Bottles”

A well-known adage captures perfectly this sentiment: “You cannot put old wine in new bottles and call it a new vintage.” The “wine”—the core policies and approaches—has remained largely unchanged. Programmes like Operation Wealth Creation are repackaged or expanded into initiatives like the Parish Development Model, but the underlying critique of top-down, handout-based economics persists. The “new bottles”—the sleek graphic design, the voluminous page count, the new slogan—are designed to distract from the taste of a vintage that has, for many, failed to mature. It is a theatrical performance where the script is decades old, but the costumes are new.

The “new bottles”—the sleek graphic design, the voluminous page count, the new slogan—are designed to distract from the taste of a vintage that has, for many, failed to mature. It is a theatrical performance where the script is decades old, but the costumes are new.3. The Theatrics of Progress Versus The Reality of Stasis

For the manifesto to be a “reincarnation,” it must point to past lives. This is done by anchoring its narrative of success not in the immediate, accountable five-year term, but in a long arc stretching back to 1986. By comparing Uganda today to the nation emerging from the turmoil of the 1980s, any marginal improvement can be framed as a monumental “gain.” This cleverly sidesteps more pressing, contemporary questions. Why, after 40 years, do we still speak of “fighting corruption” as a future goal rather than a concluded battle? Why does the promise of a functional Standard Gauge Railway or enduring national roads feel like a recurring dream? The manifesto, in this light, becomes a document that celebrates past battles won to avoid scrutiny of the present war being lost against stagnation.4. A Patriotic Plea for a New Script

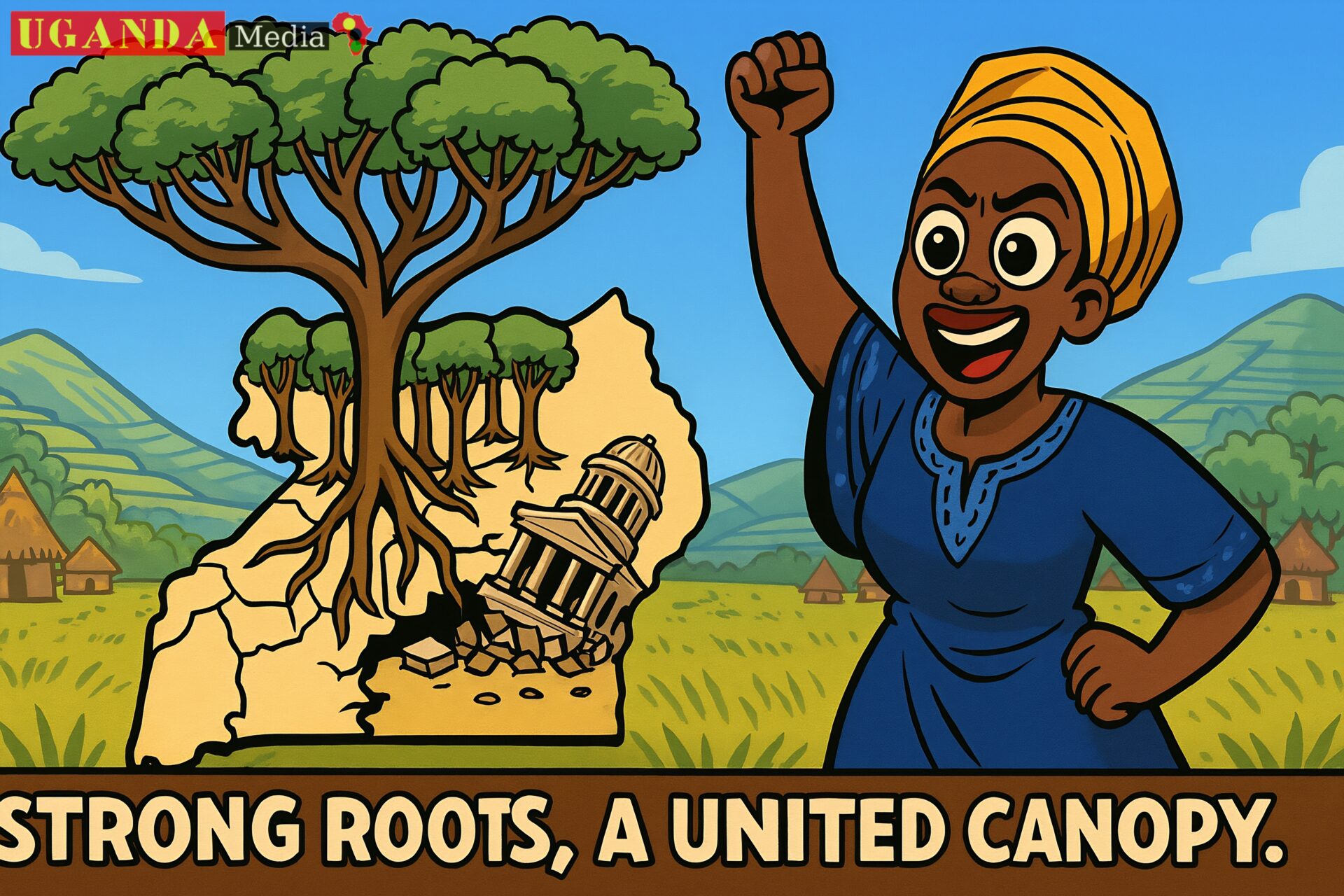

This critique is not born of mere cynicism; it is a revolutionary and nationalistic cry for the nation to break free from this cycle. True patriotism is not blind loyalty to a single narrative, but a passionate demand for one’s country to live up to its boundless potential. Uganda is a land teeming with the energy of its youth, the wisdom of its elders, and the riches of its soil. To be presented with a “reincarnated” manifesto is to be told that this dynamic, ever-evolving nation must be content with a recycled vision. It is an insult to the innovative spirit of the Ugandan people.The revolutionary call, therefore, is not for chaos, but for genesis over reincarnation. It is a demand for a political discourse that is as vibrant, creative, and forward-looking as the nation itself. It asks: when will we stop repackaging the past and instead dare to draft an entirely new script—one written with the ink of fresh ideas, bold accountability, and an unwavering belief that Uganda deserves more than a perpetual political groundhog day? The future of the Pearl of Africa depends not on protecting the gains of yesterday, but on having the courage to sow entirely new fields for tomorrow.

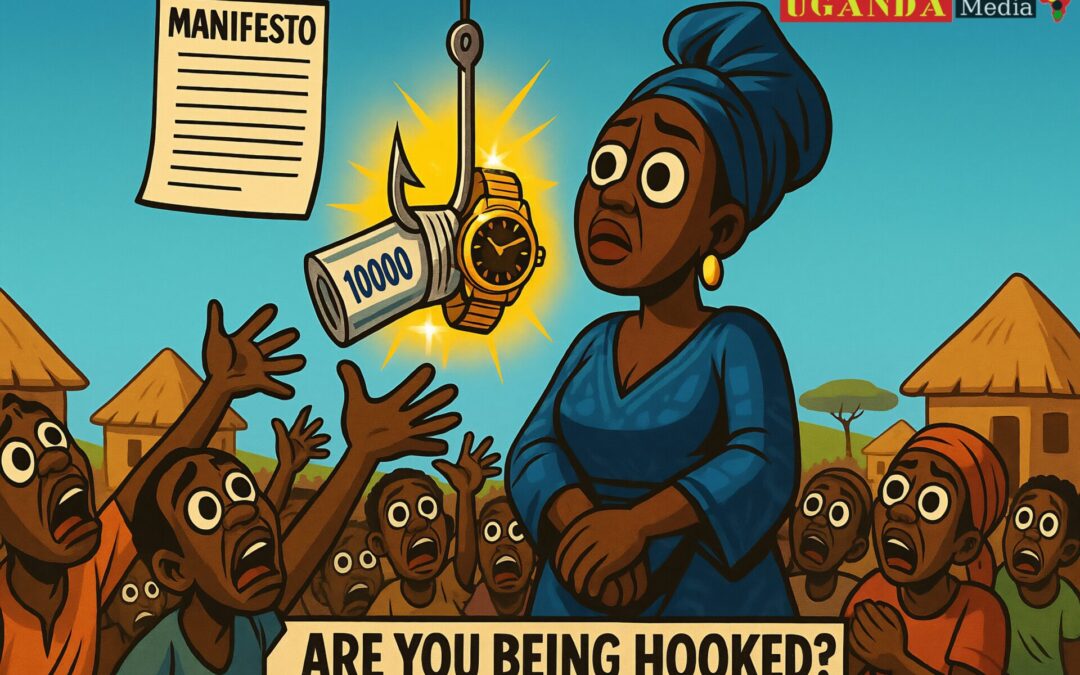

The Fishing Hook and the Hungry Fish: The Politics of Survivalism in Uganda

In the grand, vibrant market of Ugandan politics, a profound and unsettling transaction takes place every election cycle. It is not an exchange of visionary ideas for national renewal, but a more immediate, more desperate trade. The ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) has, over its long incumbency, perfected a strategy that political analysts term the “Politics of Survivalism.” This is the deliberate and tactical targeting of a populace’s most basic, immediate needs, not to empower them, but to ensure their continued dependence—and, by extension, their vote.

This approach is not merely a policy platform; it is a calculated political calculus that understands a fundamental, human truth, perfectly captured in the adage: “A man who is drowning will clutch at a snake.” When a population is consumed by the daily struggle for survival—for the next meal, the next school term, the next medical bill—its capacity to envision and demand long-term, transformative change is severely diminished. It will grasp at any immediate lifeline, even one that may ultimately possess a venomous sting.

The mechanics of this strategy can be broken down into three core components:

1. The Bait and the Hook: From Policy to Transaction

Initiatives like the Parish Development Model (PDM) are paraded as the government’s flagship for poverty eradication. However, when viewed through the lens of survivalism, their function appears more tactical than transformative. The model, which involves direct cash injections into parish-level savings groups, operates as the perfect “hook.”

The Bait: The immediate, tangible promise of capital—a million shillings, a promise of seeds, or a few iron sheets for a roof. In a nation where countless citizens navigate the informal economy day-by-day, this is not a development strategy; it is a survival stimulus.

The Hook: The unspoken political contract. The distribution of these resources, often timed around election cycles and managed through local party structures, creates a powerful, clientelistic bond. The message, though rarely stated explicitly, is clear: This sustenance comes from the Movement. Its continuity depends on your gratitude at the ballot box. It transforms the citizen from a rights-bearing stakeholder into a dependent client, and the state from a duty-bound institution into a patron.

2. The Cycle of Strategic Dependency

A transformative policy would aim to make itself obsolete—to equip people with the skills, infrastructure, and economic environment to graduate from dependency. The politics of survivalism, conversely, requires that dependency be managed, not solved.

The revolutionary critique here is that this system is designed to create a permanent class of supplicants, not a generation of innovators and entrepreneurs. By focusing on handouts that address symptoms (a lack of immediate cash) rather than causes (a lack of industrial jobs, exploitative agricultural value chains, and crippling market access issues), the system ensures the “drowning man” never quite learns to swim. He is merely kept afloat just long enough to be grateful, and to need another lifeline when the next election comes around. This creates a vicious cycle where national potential is sacrificed for short-term political security.

The revolutionary critique here is that this system is designed to create a permanent class of supplicants, not a generation of innovators and entrepreneurs. By focusing on handouts that address symptoms (a lack of immediate cash) rather than causes (a lack of industrial jobs, exploitative agricultural value chains, and crippling market access issues), the system ensures the “drowning man” never quite learns to swim. He is merely kept afloat just long enough to be grateful, and to need another lifeline when the next election comes around. This creates a vicious cycle where national potential is sacrificed for short-term political security.3. A Patriotic Call for a Liberation of Ambition

To critique this system is not to scorn the struggling Ugandan who accepts the help. It is a revolutionary and deeply nationalistic act to demand better for one’s compatriots. True patriotism is believing that the people of Uganda—from the fertile hills of Kigezi to the vast plains of Karamoja—are capable of so much more than perpetual survival.

The politics of survivalism is an insult to the ingenuity of the Ugandan spirit. It is a philosophy that tells the youth that their future is a bag of maize flour, not an industrial park or a tech hub. It tells the farmer that his destiny is a handout, not ownership of a fully integrated agricultural value chain. It is a small-minded vision for a nation of boundless potential.

The radical alternative, therefore, is not a different set of handouts, but a complete rejection of the survivalist paradigm itself. It is a call for a political revolution that shifts the entire narrative—from one of managing poverty to one of unleashing national prosperity. It demands a transition from a government that acts as a patron, doling out meagre rations to keep the people quiet, to one that acts as a visionary, building the railways, providing stable electricity, ensuring quality education, and creating a fair economic playing field that allows every Ugandan to become the architect of their own destiny.

The ultimate liberation for Uganda is not just political; it is economic and psychological. It is to move from a nation of individuals clutching at snakes to a nation of sovereign citizens, standing on the solid ground of their own productivity and self-reliance, building a future that is truly, and profoundly, their own.

The Strong Roof and the Fearful Home: The Chasm Between Security and Peace in Uganda

In the heart of every Ugandan, from the bustling trading centres of Kikuubo to the serene shores of Lake Bunyonyi, lies a fundamental desire: to live a life of tranquillity, free from fear and full of promise. The National Resistance Movement (NRM) government rightly points to a singular, monumental achievement in this regard: national security. They have built a strong roof over the nation, one that has largely protected the country from the storms of interstate conflict and the torrential rains of large-scale, organised rebel insurgencies that once plagued our land. For this, they receive due credit. A nation cannot function if it is perpetually at war with itself or its neighbours.

However, a crucial and revolutionary distinction must be made, one that separates the existence of a roof from the quality of life for those dwelling beneath it. This is the profound difference between national security and individual peace.

One is a structural achievement; the other is the lived experience of the citizen. And in today’s Uganda, a disturbing paradox has emerged: the roof stands strong, but the house is filled with a cold draught of apprehension.

1. The Architecture of National Security

National security, as presented by the state, is macro-level stability. It is the absence of war. It is the ability for goods to move on highways without the threat of ambush. It is the deployment of the army to border regions to deter foreign incursions. It is the visible presence of security apparatuses—the police, the military—as symbols of state control and order. This is the “peace” that is often proclaimed from podiums and printed in manifestos. It is a statistic, a geopolitical fact. It is the assurance that the nation-state, as an entity, is not under immediate threat of collapse.

2. The Erosion of Individual Peace

Yet, true peace is not merely the absence of war; it is the presence of justice, the assurance of safety, and the freedom to breathe easily in one’s own home. This is where the architecture fails the people. Individual peace is undermined by a pervasive climate of fear, a climate cultivated by several chilling realities:

The Weaponisation of the Law: When the very laws designed to protect the citizen are perceived as tools for intimidation—be it through the misuse of charges of incitement to violence or the abusive application of public order management—the individual’s peace is shattered. The fear of a midnight knock on the door, of being detained without charge, of facing a politicised judicial process, is a toxin that poisons the soul of a nation.

The Spectre of Unaccountable Force: The heavy-handed dispersal of gatherings, the documented cases of enforced disappearances, and the alleged torture of individuals in safe houses, create a society where people are afraid to assemble, to speak freely, or to challenge prevailing orthodoxies. This is not peace; it is the quiet of the graveyard, a silence enforced by dread.

The Psychological Cage: This environment constructs an invisible prison. As the adage goes, “A bird that lives in a cage thinks flying is an illness.” A generation is being conditioned to believe that to question, to dissent, to demand accountability, is a dangerous and unnatural act. This psychological captivity, where self-censorship becomes a survival instinct, is the absolute antithesis of peace.

3. A Patriotic Demand for Wholeness

To highlight this distinction is not to be ungrateful for the roof overhead. It is a revolutionary and deeply nationalistic act to demand that the house be made a home. True patriotism is believing that Uganda deserves more than just the basic, structural assurance against chaos; it deserves a holistic peace that nourishes every single citizen.

A nation is not truly secure if its mothers fear for their sons who speak out. A country is not at peace if its entrepreneurs must navigate a labyrinth of patronage and intimidation to succeed. A land is not tranquil if its artists and writers must clip their own wings for fear of reprisal.

The call, therefore, is for a new social contract—one that understands that national security is the floor, not the ceiling. The ultimate goal must be a sovereign peace, a peace that is rooted not in fear, but in justice, dignity, and the unshakeable freedom of the individual. We must strive for a Uganda where the strength of the state is measured not by the silence it imposes, but by the confident, vibrant, and unafraid voices of its people, living in genuine and profound peace.

The call, therefore, is for a new social contract—one that understands that national security is the floor, not the ceiling. The ultimate goal must be a sovereign peace, a peace that is rooted not in fear, but in justice, dignity, and the unshakeable freedom of the individual. We must strive for a Uganda where the strength of the state is measured not by the silence it imposes, but by the confident, vibrant, and unafraid voices of its people, living in genuine and profound peace.The Forest of Overseers and the Barren Field: The Paralysing Bloat of the Ugandan State

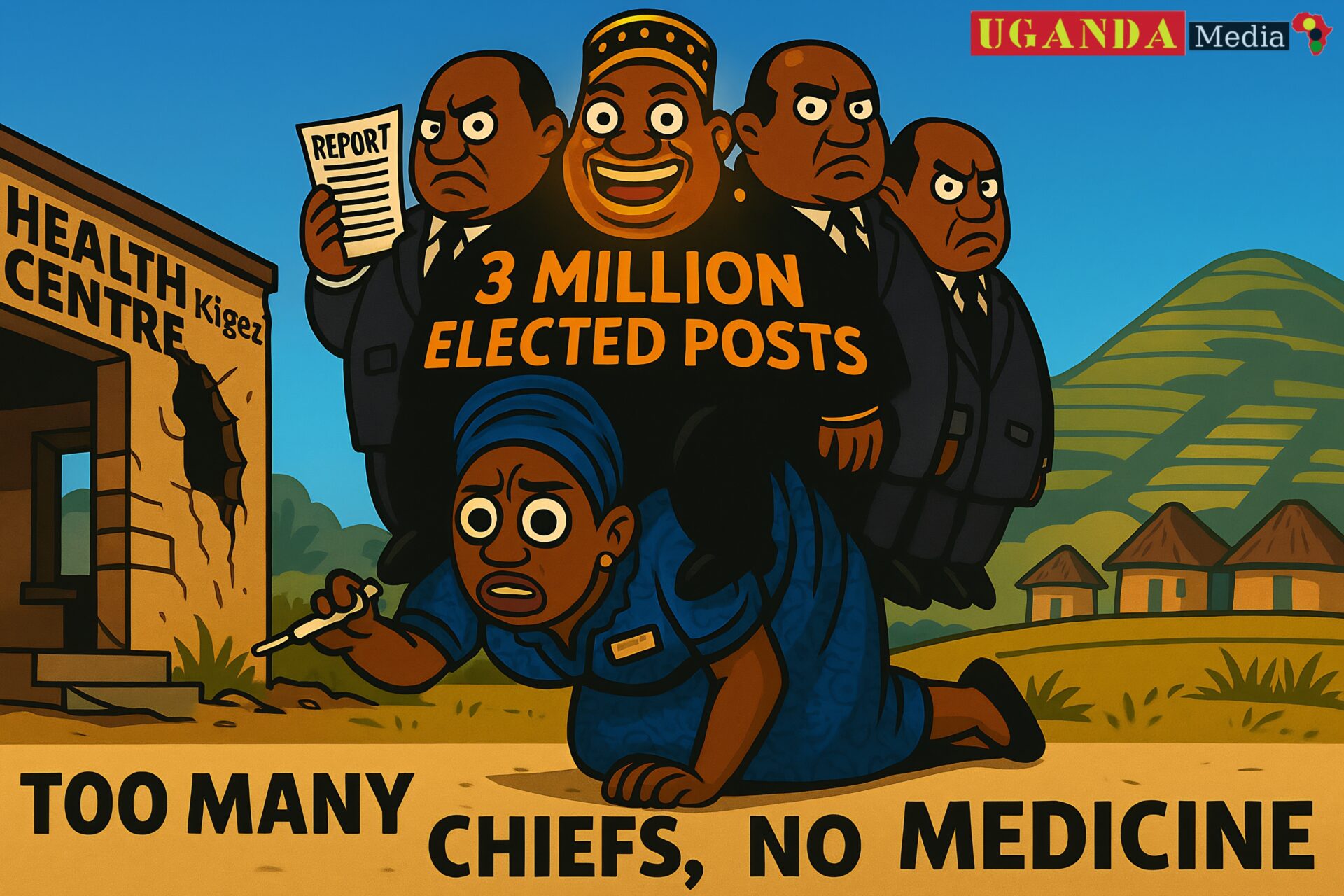

In the quest to build a modern nation, a fundamental principle of governance is that a state should serve its people, not suffocate them. Yet, in Uganda, a monstrous and paradoxical creation has taken root: a governmental Leviathan so vast and convoluted that it now actively hinders the very progress it was designed to foster. This is the crisis of the bloated state, a system where the architecture of oversight has become so inflated that it dwarfs the foundation of service delivery.

The statistics are as staggering as they are illogical: nearly three million elective posts. To comprehend this figure is to imagine a scenario where, for every handful of Ugandans engaged in the productive work of healing, teaching, or building, there stands a small committee elected to monitor, supervise, and report on their efforts. We have meticulously cultivated a vast forest of overseers, but the fields of national progress lie increasingly barren.

This predicament can be understood through its three most corrosive consequences:

1. The Tyranny of the Monitor over the Producer

The relationship between the civil servant—the teacher, the nurse, the engineer—and the political office-holder has been inverted. The 367,000 civil servants who form the backbone of public service are now outnumbered by a political class of millions. This creates a system not of facilitation, but of perpetual inspection. The teacher in a primary school in Lira is answerable to a hierarchy of local councillors, who are themselves answerable to sub-county and district officials, all the way up. The energy and resources that should be channeled into purchasing textbooks and repairing classrooms are instead consumed by writing reports for, and attending meetings with, an endless procession of monitors. This embodies the adage, “Too many cooks spoil the broth.” We have a nation where the cooks now spend all their time in meetings about cooking, while the pot remains empty.2. The Systemic Cultivation of Red Tape and Corruption

This labyrinthine structure is not merely inefficient; it is a meticulously engineered ecosystem for corruption and patronage. Every new district, every new constituency, and every new political office creates fresh nodes for the allocation of resources—for salaries, allowances, vehicles, and offices. This diverts colossal sums of the national budget away from direct service delivery and into the self-sustaining machinery of political administration.The revolutionary critique here is that this is not an accident; it is a strategy. A populace entangled in red tape, chasing a signature from one office to the next, is a populace disempowered and easier to manage. Furthermore, this bloat serves as a vast system of patronage, where loyalists are rewarded with political positions, cementing a culture where loyalty to the system is valued far more than competence in service. It is a grand, national-scale clientelism, funded by the very taxpayers it fails to serve.

3. A Patriotic Call for a Sovereignty of Service

To demand the slimming of this bloated state is not a call for less governance; it is a revolutionary and nationalistic demand for better governance. It is a call for a Sovereignty of Service, where the citizen is the ultimate master and the state is a lean, efficient, and accountable servant.True patriotism is believing that Uganda’s immense potential is being strangled by this self-created bureaucracy. The resources spent on maintaining two million monitors could instead build hospitals, equip universities, and power industries. The human capital wasted in redundant administrative roles could be unleashed to innovate, produce, and drive the nation forward.

We must therefore wage a peaceful, intellectual revolution against this bloat. The goal is to dismantle the forest of overseers and replant the field of productivity. It is to champion a radical devolution of power and resources not to another layer of politicians, but directly to the communities, the schools, the health centres, and the productive sectors. It is to envision a Uganda where a citizen interacts with a responsive, automated system to get a permit, not a dozen different office-holders; where a teacher is esteemed above a local councillor; where the budget for a new road is not swallowed by the allowances for the committee formed to oversee its non-construction.

The liberation of Uganda’s potential hinges on this decongestion. We must transform the state from a suffocating Leviathan into a sleek vessel, capable of navigating the fierce currents of the 21st century and delivering its people to the shores of prosperity they so richly deserve.

The Architect’s Blueprint vs. The Painter’s Brochure: The Substance of the Opposition’s Pitch

In the grand marketplace of political ideas, where the incumbent sells the repackaged past, a different stall is being set up by the collective opposition. Parties like the Alliance for National Transformation (ANT), the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC), and the National Unity Platform (NUP) are attempting a fundamentally different sales pitch. Their manifestos are not merely volumes of aspiration; they are presented as detailed blueprints, replete with measurable targets, specific timelines, and costed policies. This shift from vague promise to quantifiable plan represents a significant evolution in Uganda’s political discourse, framing the 2026 election as a choice between a comforting fantasy and a difficult, yet tangible, reality.

This policy-centric approach can be dissected through its three most compelling facets:

1. The Precision of Promise: From “Development” to Data Points

The key differentiator lies in the move from the abstract to the concrete. Where the ruling party speaks in grand, unassailable themes like “wealth creation,” the opposition is attempting to drill down to the specifics. Their documents are noted for containing quantifiable targets:Pledging to raise industrial contribution to GDP from 20% to 30% by a specific year.

Committing to create a defined number of jobs for the youth, often targeting a 60% reduction in youth unemployment.

Vowing to recover a specific sum—the oft-cited 10 trillion shillings—lost annually to corruption.

This approach functions as a tangible contract with the citizenry. It is the difference between an artist’s beautiful but abstract painting of a house and an architect’s detailed blueprint, complete with dimensions, materials, and a bill of quantities. The former inspires a feeling; the latter enables accountability. As the adage goes, “The devil is in the details,” but so too is the proof of genuine intent. By providing details, the opposition is offering voters a yardstick with which to measure them, a calculated risk that signals a confidence in their own plans and a respect for the intelligence of the electorate.

2. The Anatomy of Fiscal Rectitude: A War on Waste

A central pillar of this policy pitch is a direct assault on the NRM’s most glaring failures: fiscal indiscipline and soaring public debt. The opposition narratives are unified in their condemnation of a system that operates on a cascade of supplementary budgets, rendering the national budget a meaningless ritual.Their proposals are revolutionary in their clarity:

Slaying the Leviathan: A commitment to cut the bloated public administration, reducing the number of districts and political offices, thereby freeing up billions for direct service delivery.

Debt Renegotiation: A pledge to audit and renegotiate “unfair and expensive loans” that have mortgaged the nation’s future.

Broadening the Tax Base: A focus on formalising the economy and making taxation more equitable, rather than squeezing existing taxpayers dry.

This is not just an economic policy; it is a moral stance. It frames the current government’s fiscal management not as incompetence, but as a betrayal of the national trust, a deliberate impoverishment of the state for the benefit of a few. The opposition presents itself as the responsible custodian, ready to clean the Augean stables of the national treasury.

3. The Nationalistic Imperative: A Call to Build, Not Beg

Underpinning these technical proposals is a powerful, revolutionary, and deeply nationalistic narrative. It is a call for Uganda’s sovereign awakening. The opposition’s pitch argues that the politics of survivalism and the economics of debt have reduced the nation to a beggar in the international community, its policies dictated by foreign creditors and its resources sold for a pittance. The promise of a diversified, industrialised economy is thus framed as an act of national liberation. It is a vision of a Uganda that is not merely a supplier of raw coffee beans and unprocessed minerals, but a manufacturer of finished goods. It is a vision where Ugandan engineers, not foreign contractors, maintain the railways, and where Ugandan capital funds Ugandan enterprise.

The promise of a diversified, industrialised economy is thus framed as an act of national liberation. It is a vision of a Uganda that is not merely a supplier of raw coffee beans and unprocessed minerals, but a manufacturer of finished goods. It is a vision where Ugandan engineers, not foreign contractors, maintain the railways, and where Ugandan capital funds Ugandan enterprise.This is the ultimate contrast. It is a choice between a government that gives you a fish, fostering a culture of dependency, and a leadership that promises to drain the swamp, teach you to build a net, and restore the river’s health so you can feed yourself and your nation for a lifetime. The opposition’s policy pitch, in its most potent form, is an invitation to participate in a national rebirth—to exchange the fragile security of the handout for the sovereign dignity of self-reliance, and to build a Uganda that is not merely secure, but truly prosperous and master of its own destiny.

The Beautiful Bus with a Broken Engine: The Trust Deficit Plaguing Uganda’s Opposition

The political opposition in Uganda presents a compelling, even seductive, vision. Their manifestos are not mere pamphlets; they are detailed blueprints for a different nation, promising a radical departure from the politics of survival and stagnation. They speak the language of data, of industrialisation, of fiscal responsibility—a symphony of sensible governance that resonates with a populace weary of empty slogans. Yet, hanging over this polished presentation is a single, deafening question from the very people they seek to liberate: “After all we have seen, can we truly trust you with the keys?”

This is not the scepticism of cynics, but the warranted caution of a people who have been promised liberation before, only to be delivered into new forms of servitude. The trust deficit is a chasm forged in the fire of the opposition’s own internal contradictions and a political history that has taught Ugandans to be wary of all who seek power.

This crisis of confidence stems from three fundamental sources:

1. The Contradiction of the ‘Democratic’ Autocrat

A party that campaigns on the platform of democratic restoration and accountable governance immediately forfeits its moral authority when its internal structures are shrouded in secrecy, centralised control, and the suppression of dissent. The very same parties that rightly condemn the NRM’s monolithic structure often replicate it in microcosm. When a seasoned, outspoken legislator is unceremoniously dropped in favour of a politically novice musician, the message sent is not one of meritocracy, but of patronage and blind loyalty. When internal debates are stifled and decisions are handed down from a small, unelected clique, it reveals a profound hypocrisy. It demonstrates that the thirst for power is not to serve the people, but to replace the current occupants of the throne. As the adage goes, “A leaking pot cannot hold water.” How can a political organisation that cannot manage its own internal affairs without acrimony and exclusion be trusted to manage the complex, leaking vessel of the Ugandan state? The public sees the beautiful, newly painted bus, but they have grave doubts about the competence and intentions of the drivers fighting over the wheel.

When a seasoned, outspoken legislator is unceremoniously dropped in favour of a politically novice musician, the message sent is not one of meritocracy, but of patronage and blind loyalty. When internal debates are stifled and decisions are handed down from a small, unelected clique, it reveals a profound hypocrisy. It demonstrates that the thirst for power is not to serve the people, but to replace the current occupants of the throne. As the adage goes, “A leaking pot cannot hold water.” How can a political organisation that cannot manage its own internal affairs without acrimony and exclusion be trusted to manage the complex, leaking vessel of the Ugandan state? The public sees the beautiful, newly painted bus, but they have grave doubts about the competence and intentions of the drivers fighting over the wheel.2. The Spectre of Recycled Personnel and Recycled Politics

The trust deficit is deepened by the uncomfortable reality of political recycling. The faces that appear in opposition ranks are often the same figures who were once integral parts of the very system they now decry. They are former ministers, advisors, and beneficiaries of the NRM structure who, having fallen out of favour or failed to achieve their personal ambitions, now posture as champions of change.To the ordinary Ugandan, this creates a terrifying question: are we being offered a genuine alternative, or merely a change of management for the same exploitative enterprise? The fear is that an opposition victory would not be a revolution, but a reshuffling of the deck—a change of the guard, not of the guard’s mentality. The suspicion is that the blueprints for reform are merely a Trojan Horse, behind which lie the same old desires for access to state resources and the privileges of power. The struggle begins to look less like a principled fight for liberation and more like a contest between two wings of the ruling class for control over the national treasury.

3. A Radical Demand for a New Political Genesis

This profound distrust is not an endpoint; it is the most potent starting point for a truly radical and leftist re-imagining of power itself. The failure of the established opposition is not a tragedy, but a revelation. It reveals that the problem is not merely one of personnel, but of the entire structure of representative politics and the state itself.The scepticism of the masses is, in fact, a healthy and correct instinct. It is an understanding that power, in its current concentrated form, corrupts absolutely, regardless of the colour of the flag it flies. Therefore, the radical demand is not for a better set of rulers, but for the dissolution of the very idea that a small group should rule over the many.

The answer to the trust deficit is not to plead for faith in new leaders, but to build power from the ground up, in a way that makes such blind faith unnecessary. It is to champion a system where:

Power is Horizontal, Not Vertical: Where decisions are made in village assemblies, workers’ councils, and community cooperatives, not in distant party headquarters or Parliament.

Recallable Delegates Replace Career Politicians: Where those tasked with administrative duties can be instantly recalled by their communities if they betray their mandate, ensuring that power remains with the people, not with a political class.

The Community Controls the Resources: Where the wealth of the land—from the oil in the Albertine Graben to the fertile soils of Busoga—is managed and enjoyed collectively by the communities that inhabit it, breaking the state’s monopoly on patronage.

The opposition’s trust deficit is their greatest weakness, but it is the people’s greatest strength. It is a clear sign that Ugandans are not easily fooled. The path forward is to reject the false choice between a known dictator and a potential one. It is to build a different kind of power altogether—one rooted in mutual aid, direct action, and the unshakeable sovereignty of the people over their own lives and labour.

The future of Uganda does not lie in trusting a new set of masters, but in trusting ourselves to build a world where masters are no longer needed.

The future of Uganda does not lie in trusting a new set of masters, but in trusting ourselves to build a world where masters are no longer needed.The Master Builder’s Illusion: Why Uganda’s Crisis is One of Leadership, Not Blueprints

In the earnest discussions about Uganda’s future, a dangerous illusion persists: the belief that the nation’s primary ailment is a lack of sophisticated plans. We meticulously dissect manifestos, compare policy proposals, and debate economic models as if we are architects squabbling over blueprints for a magnificent new city. Yet, this entire debate wilfully ignores the most glaring, foundational truth: We are not standing on an empty plot of land. We are standing in the midst of a dilapidated, half-built structure, plagued by faulty workmanship and pilfered materials, all under the direction of the same foreman for nearly four decades. The problem is not the design on paper; it is the profound and deep-seated crisis of leadership and accountability in the foreman’s office.

This argument posits that all manifestos, regardless of their intellectual elegance, are rendered meaningless when placed in the hands of a political class that has demonstrated a consistent disregard for the public good. The crisis is not one of ideas, but of character; not of vision, but of virtue.

This leadership deficit manifests in three catastrophic ways:

1. The Cult of the Individual Over the Collective

True leadership is meant to be a stewardship, a temporary responsibility held in trust for the people. In Uganda, it has been transformed into a form of ownership. The state is treated as a private estate, its resources a personal treasury, and its citizens as tenants on the land. This perversion explains why the most beautifully costed manifesto is doomed. It assumes that those in power will be honourable administrators, when the entire structure of the state has been reconfigured to serve the interests of a few.As the piercing adage goes, “A fish rots from the head down.” The systemic corruption, the endemic cronyism, and the blatant nepotism that filters through every government department are not isolated failures; they are the direct consequence of a leadership that has, from the top, prioritised self-enrichment and political survival over national service. You cannot build a straight wall with a crooked plumb line. No policy, however well-intentioned, can survive contact with a system designed to divert its benefits.

2. The Architecture of Unaccountability

A leader is only as good as the constraints placed upon them. Uganda’s crisis is exacerbated by a deliberate and systematic dismantling of every pillar of accountability. When the Parliament functions as a cheering squad rather than a check on power, when the judiciary is perceived as an instrument of political convenience, and when the media is cowed into a whisper, the leadership is liberated from all consequences.This creates an environment where failure is rewarded, incompetence is promoted, and corruption is monetised. A leader who knows they will never be held to account for a failed policy or a stolen trillion has no incentive to follow a manifesto. The document becomes a mere brochure, a piece of campaign theatre to be discarded the moment the votes are counted. The very concept of a social contract—where leaders are accountable to the led—has been severed.

3. A Radical Call for Collective Sovereignty

The conclusion from this analysis is not to seek a new, better leader. That is the old, failed logic of the saviour. The leftist and fundamentally radical response to the leadership crisis is to declare that the people must become their own leaders.This is a call to dismantle the very pyramid of power that concentrates authority in the hands of a few and makes accountability impossible. It is an argument for a new way of organising society:

From Vertical Power to Horizontal Power: Shifting decision-making from a distant, corrupt State House to community assemblies in the villages of Kumi and the wards of Kisenyi. Let the people who are affected by a decision be the ones to make it.

From Representation to Direct Action: Replacing the faith in a political class that consistently betrays its promises with the power of self-organised communities. Let teachers’ cooperatives manage education, let farmers’ unions control agricultural markets, and let neighbourhood councils oversee local security and infrastructure.

The Death of the Master Builder: This philosophy rejects the need for a single, all-powerful foreman. It asserts that a million Ugandans, working together in their own communities, with control over their own resources and destinies, can build a far stronger and more just nation than any single leader or party ever could.

The leadership crisis will not be solved by finding the right person for the crown. It will only be solved by breaking the crown itself and distributing its fragments—its power, its responsibility, its sovereignty—to every single citizen. The future of Uganda does not lie in the palace; it lies in the power of the people, organised, conscious, and finally controlling their own collective destiny.

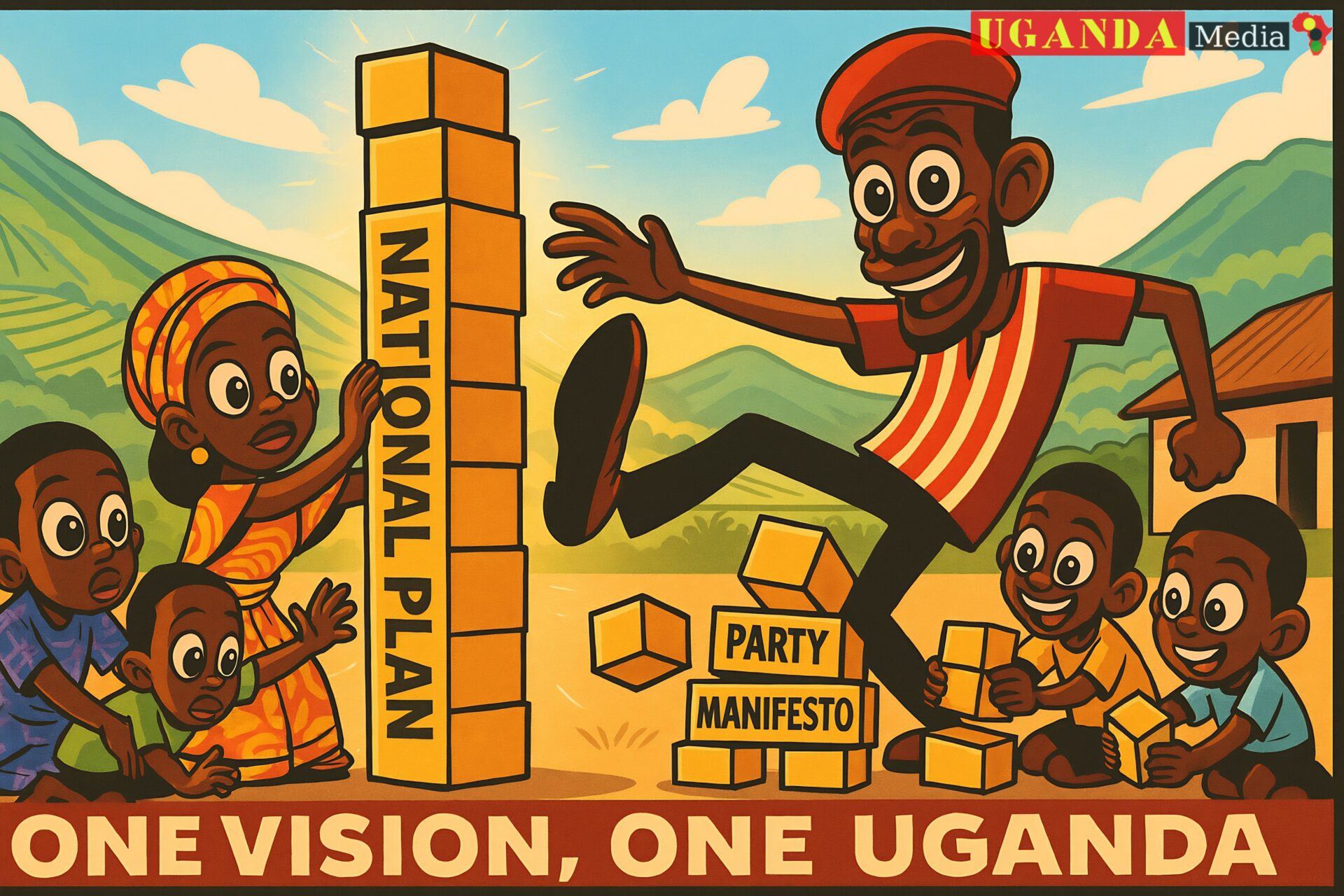

Beyond the Political Carnival: The Case for a Ugandan National Destiny Plan

Amid the cacophony of the electoral season—the roaring convoys, the vibrant posters, the grand promises—a profound and revolutionary idea challenges the very premise of our political theatre. It is the argument that Uganda’s fundamental error is to treat national development as a partisan football, to be kicked in a new direction with every change of goalkeeper. This critique posits that we must shift our focus from the narrow, party-specific manifestos that serve as campaign tools and rally behind a singular, enduring, and sovereign National Destiny Plan.

This is not a call for a government policy; it is a demand for a national covenant—a sacred pact between the people and their future, transcending the petty ambitions of any individual or political organisation. It recognises that building a nation is a generational endeavour, not a five-year sprint.

This is not a call for a government policy; it is a demand for a national covenant—a sacred pact between the people and their future, transcending the petty ambitions of any individual or political organisation. It recognises that building a nation is a generational endeavour, not a five-year sprint.The argument for this paradigm shift rests on three powerful pillars:

1. The Failure of Partisan Myopia

The current system of party manifestos is inherently flawed and divisive. It encourages a political culture where the incoming regime has a perverse incentive to neglect or dismantle the projects of its predecessor, not because the projects are unsound, but simply because they bear another party’s name. This creates a catastrophic cycle of waste and stagnation, where half-built hospitals and abandoned road projects litter the landscape like monuments to political vanity.As the adage goes, “a family that builds together, grows together.” Yet, we have allowed our national family to be fractured into warring factions, each with its own blueprint for the house, each tearing down what the last one started. This is not development; it is a perpetual demolition derby disguised as progress. A National Plan would serve as the foundational architecture agreed upon by the entire family, ensuring that every generation, regardless of its political leanings, continues to build upon the same walls, raising the roof higher for all.

2. The Vision of a People’s Plan

A true National Destiny Plan would not be drafted in secret by party technocrats. Its creation would itself be a revolutionary act of mass participation. Imagine a process where village assemblies in Nebbi, town hall meetings in Mbale, and workers’ unions in Kampala collectively define the nation’s non-negotiable priorities for the next quarter-century.This would enshrine the people’s will on fundamental questions:

What is the minimum standard of healthcare and education every Ugandan deserves?

What is the definitive, phased timeline for connecting every village to the national grid and clean water?

How do we structurally transform our economy from a raw material exporter to an industrial and knowledge-based powerhouse?

This plan becomes the people’s instruction manual to their government, a document of sovereign will that is immutable to the whims of a changing political wind.

3. The Shift from ‘Who Rules’ to ‘Who Can Best Serve’

Under this new paradigm, the role of political parties is radically transformed. They are neutered of their power to derail the national trajectory. Their purpose is no longer to sell their own unique, and often unrealistic, vision of the future. Instead, they must come before the people and compete on a single, crucial question: “Given the agreed National Plan, which of us has the competence, integrity, and team to implement it most effectively and efficiently?”Elections become a contest of administrative skill, not a clash of contradictory ideologies. It forces parties to showcase their engineers, their project managers, and their accountable leaders, not just their charismatic orators. It moves the political debate from the abstract clouds of promise to the solid ground of implementation, auditing the previous term’s performance against the fixed metrics of the National Plan.

This is the ultimate expression of people power. It dismantles the cult of the leader and establishes the supremacy of the collective will. It tells the political class, in no uncertain terms: “You are not our masters, coming to impose your vision upon us. You are our temporary servants, applying for the job of executing our vision.” It is a call to end the political carnival and begin the serious, solemn, and sovereign work of building a Uganda that truly belongs to all its people, once and for all.

The Potemkin Village Nation: Uganda’s Perpetual Cycle of Infrastructure Mirages

In the grand narrative of Ugandan development, infrastructure projects occupy a sacred space. They are the colossal, tangible proofs of progress that governments promise and citizens desperately crave. Yet, for decades, a haunting spectre has stalked the landscape of our national ambition—the Ghost of Infrastructure Past. This is not a singular phantom, but a collective presence: the legion of projects that live eternally in the realm of promise, perpetually relaunched, re-announced, and rescheduled, but never realised. They are the political equivalent of mirages in the Karamoja plains— shimmering visions of progress that vanish as one approaches, leaving only the dusty reality of the status quo.

The most potent symbol of this ghost is the Standard Gauge Railway (SGR). It is a project that has been so thoroughly announced and re-announced that it has become a national punchline, a ritualised promise devoid of meaning. Like a recurring dream, it appears in every manifesto, at every campaign rally, a testament to a future that never arrives. This phenomenon reveals a political system that has mastered the theatre of development while evading its substance.

The most potent symbol of this ghost is the Standard Gauge Railway (SGR). It is a project that has been so thoroughly announced and re-announced that it has become a national punchline, a ritualised promise devoid of meaning. Like a recurring dream, it appears in every manifesto, at every campaign rally, a testament to a future that never arrives. This phenomenon reveals a political system that has mastered the theatre of development while evading its substance.This cycle of broken infrastructure promises can be understood through three interconnected deceptions:

1. The Spectacle of the New vs. The Neglect of the Existing

A central tactic is the perpetual announcement of new, grand projects to distract from the catastrophic neglect of existing infrastructure. While the government dazzles the public with artist’s impressions of a gleaming SGR, the arteries of our current economy—the national road network—are in a state of perpetual collapse.The Kampala-Masaka highway develops crippling potholes. The Mbale-Soroti road becomes a trial of endurance. The bridge at Karuma becomes a bottleneck. This is not accidental; it is strategic. As the adage goes, “a leopard cannot change its spots.” A system built on patronage and the spectacle of new contracts has no functional incentive for the mundane, unglamorous work of maintenance. It is far more politically lucrative to cut the ribbon on a new, half-built project than to be held accountable for the upkeep of an old one. The ghost is not just the SGR; it is the ghost of every road that was built without a plan for its future, doomed to an early grave.

2. The Political Economy of the Perpetual Project

A project that is always “about to begin” is far more valuable to the current political model than one that is completed. A finished project becomes a public asset, subject to public scrutiny and use. A perpetual project, however, remains a political asset.It exists as a permanent entry in the budget, a continuous stream of feasibility studies, consultancy fees, and preliminary contracts that can be channelled to loyalists. It serves as a campaign promise that never has to be tested against reality. It is a tool to drum up nationalist sentiment, to present the government as a visionary force battling against complex odds. The very failure to complete it becomes part of its utility, allowing the blame to be shifted onto foreign partners, funding shortfalls, or technical complexities. The SGR is not a transport project; it is a political utility, and its continued absence is a feature, not a bug, of the system.

3. A Radical Demand for a Sovereignty of the Tangible

The leftist and revolutionary response to this ghost is not to beg for the SGR to be built. It is to fundamentally question the entire centralized, top-down model of development that produces these phantoms. It is to reject the spectacle and demand a sovereignty of the tangible.This means:

Shifting Power from the Centre to the Community: Instead of a single, multi-billion dollar SGR project controlled by a distant, corruptible ministry, imagine the same resources devolved to districts and communities for a thousand smaller, concrete projects. Let the people of Kasee decide on their feeder roads, let the communities of Lira manage their local grain stores, and let the wards of Jinja control the maintenance of their urban streets.

Valuing Use-Value over Political Value: A system built from the ground up prioritises what is actually useful. A functional, maintained rural road that gets a farmer’s goods to market is infinitely more valuable than a CGI video of a high-speed train. A reliable municipal water system is worth more than the plaque on a never-opened health centre.

Building with, not for, the People: True infrastructure is not something done to a population; it is something a population does for itself, with the state as a facilitator, not a benefactor. It is the difference between being a passive audience for a government’s theatrical productions and being the lead actors in building our own reality.

The Ghost of Infrastructure Past will continue to haunt Uganda only for as long as we consent to a politics of illusion. The exorcism lies in our collective hands. It requires us to turn away from the shimmering mirages on the horizon and focus our energy on building a real, tangible, and resilient nation from the ground up, one maintained road, one community-owned well, and one accountable decision at a time. Our future is too precious to be left to the realm of ghosts and promises.

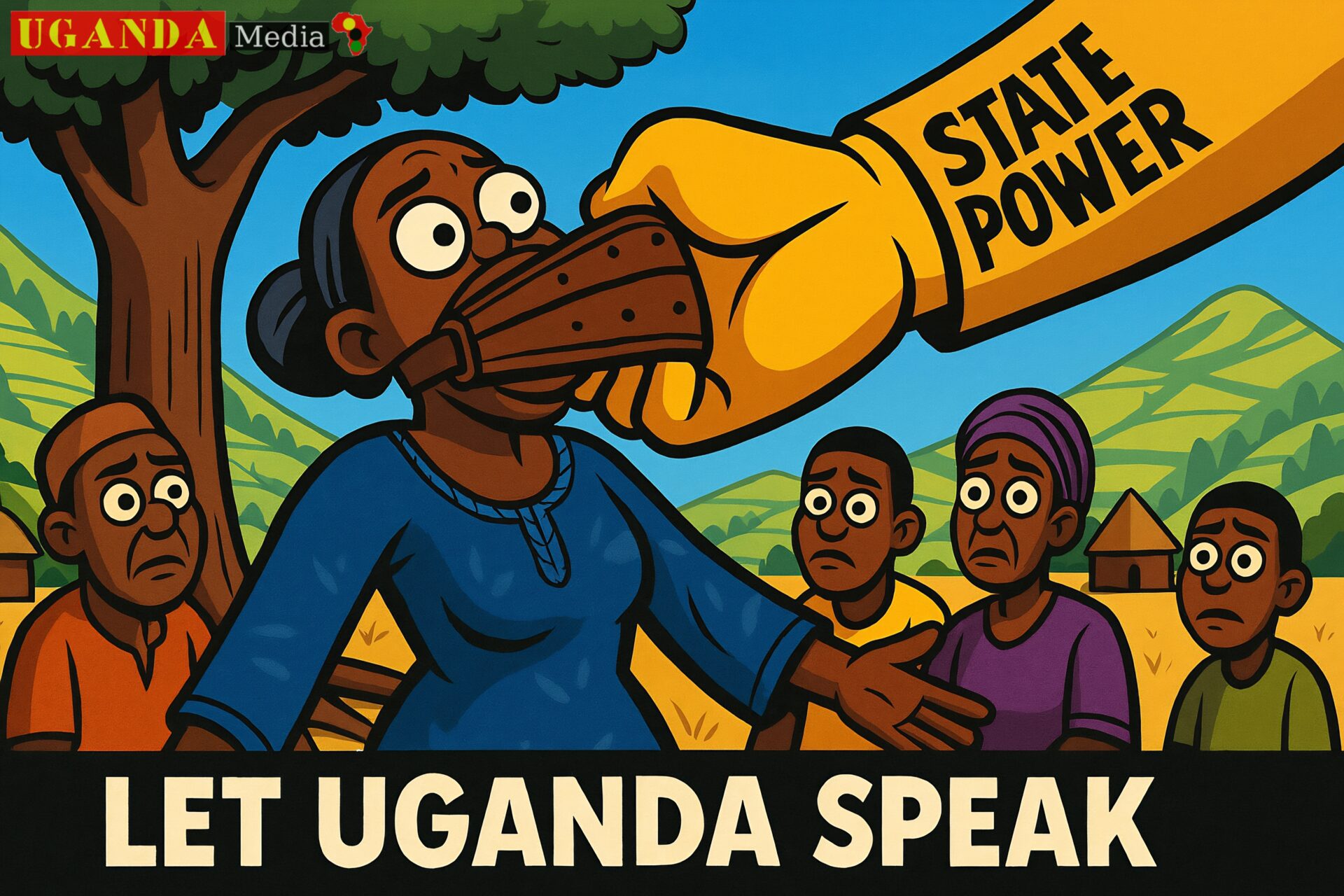

The Two Ugandas: The Chasm Between the Manifesto Page and the Dusty Road

In the air-conditioned rooms of Kampala, political manifestos are born. They are pristine documents, brimming with the language of economic models, infrastructure timelines, and social contracts. They speak to a Uganda of logic, order, and potential—a nation waiting to be built by reasonable minds. Yet, just a few kilometres outside the city limits, on the dusty, potholed trails where the actual campaign for power is waged, a different, more brutal Uganda asserts itself. This is the Uganda of the campaign trail, a realm where high-minded policy is not merely ignored, but actively suffocated by the blunt instruments of state power, revealing a political reality where the contest is not one of ideas, but of raw, unaccountable force.

This disconnection is not a minor inconsistency; it is the fundamental truth of Ugandan politics. It exposes the manifesto not as a governing agenda, but as a decoy, a piece of political theatre designed for international observers and naïve idealists, while the real battle for power is fought on a field where the rules are written by the incumbent to ensure they never lose.

This disconnection is not a minor inconsistency; it is the fundamental truth of Ugandan politics. It exposes the manifesto not as a governing agenda, but as a decoy, a piece of political theatre designed for international observers and naïve idealists, while the real battle for power is fought on a field where the rules are written by the incumbent to ensure they never lose.This reality can be broken down into its three core components:

1. The Architecture of Intimidation: The State as a Campaign Tool

The most glaring feature of the campaign trail is the weaponisation of the state. Police, whose mandate is to protect all citizens, are transformed into the enforcement arm of the ruling party. Opposition candidates find their routes mysteriously “diverted” for “security reasons,” their rallies blocked, and their supporters dispersed with tear gas and brute force.This creates a chillingly effective two-tier system. One candidate moves in a seamless, state-funded convoy, their megaphones blaring promises of development, shielded by the very officers who obstruct their rivals. The other candidate spends their day negotiating with hostile police commanders, their energy sapped not by debating policy, but by battling arbitrary arrests and navigating illegal roadblocks. The message is unmistakable: the state does not belong to you, the citizen; it belongs to the Movement. As the adage goes, “The lion’s story will never be known as long as the hunter is the one to tell it.” In this case, the state controls the narrative by physically preventing the other storytellers from speaking.

2. The Unlevel Playing Field: A Pantomime of Competition

What is presented as a democratic race is, in reality, a meticulously staged pantomime of competition. The playing field is not simply uneven; it is a vertical cliff. The incumbent commands bottomless resources from the state coffers, using government programmes, vehicles, and civil servants as extensions of their campaign machinery. Announcements of new projects or cash disbursements are strategically timed for maximum electoral impact, blurring the line between state function and campaign activity.Meanwhile, the opposition is forced to fundraise for every litre of fuel, every poster, and every loudspeaker. They are not competing against a political rival; they are competing against the entire architecture of the state, which has been repurposed as a re-election campaign. This renders their detailed manifestos almost pathetic in their irrelevance. What is the value of a sophisticated agricultural policy when your opponent is physically handing out hoes and seedlings from the back of a government truck, flanked by armed state agents?

3. A Radical Rejection of the Spectacle: The Power of the People’s Assembly

Confronted with this reality, the leftist and revolutionary conclusion is not to try to win a rigged game, but to reject the game itself and create a new one. The stark contrast between the manifesto and the trail proves that the centralised state is irredeemably corrupt and cannot be captured through its own flawed processes for the benefit of the people.The radical response is to withdraw legitimacy from this entire spectacle and to begin building people’s power from the ground up, in spite of the state. This means:

Ignoring the Stage, Building the Community: While the political circus occupies the national stage, the real work begins in the villages, the neighbourhoods, and the workplaces. It means forming popular assemblies, workers’ cooperatives, and community defence networks that operate on principles of direct democracy and mutual aid.

Creating a Counter-Power: The goal is not to petition the state for fairness, but to build a parallel, collective power so resilient that the state’s intimidation becomes irrelevant. When a community can feed itself through its own cooperative farms, educate its children through its own literacy programmes, and guarantee its own security, the power of the state to disrupt a political rally becomes a minor irritation, not an existential threat.

Direct Action Over Electoral Petition: This philosophy prioritises seizing what is rightfully the people’s—be it land, resources, or control over their own labour—rather than begging a hostile government for it. It is the difference between holding a rally to ask for a road and mobilising the community to collectively fill the potholes themselves, asserting their sovereignty over their own space.

The campaign trail reality is the truth serum of Ugandan politics. It reveals that our struggle is not for a better manifesto, but for a different kind of power altogether—a power that is not held in a state house, but woven into the fabric of every community; a power that cannot be diverted by a police roadblock because it is everywhere, belonging to everyone. It is a call to turn our backs on the staged battle at the top and to begin the real work of building a free Uganda from the ground up.

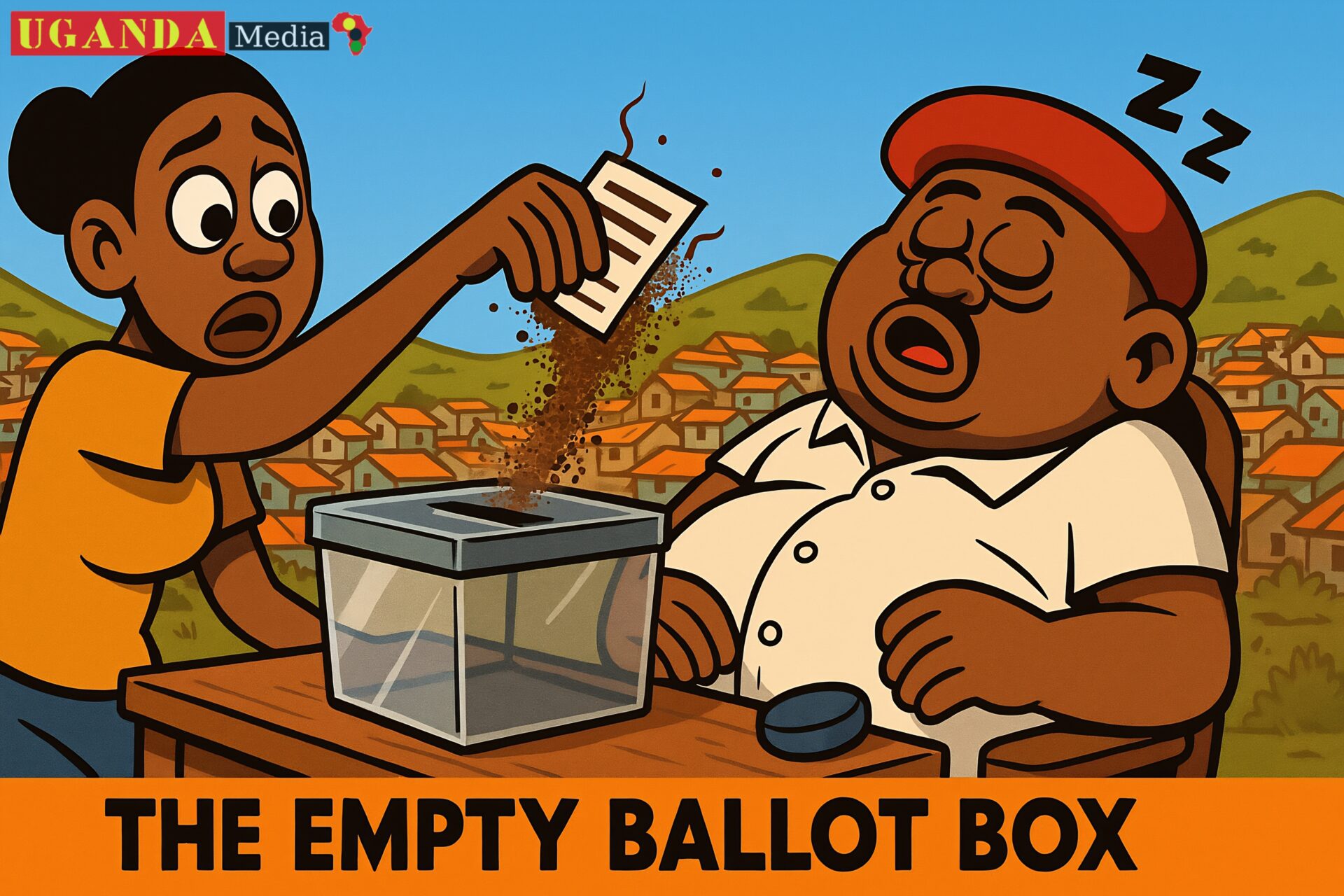

The Price of a Nation: How a ‘Rolex’ Became the Currency of Betrayal

In the vibrant, chaotic theatre of Ugandan elections, a most devastating transaction takes place. It does not occur in boardrooms or at policy seminars, but in the dusty compounds and crowded trading centres where the struggle for daily survival is most acute. Here, the sacred, sovereign power of the vote—the foundational stone upon which the entire edifice of democracy is supposed to rest—is being traded. Its price? A paltry 2,000 to 5,000 Ugandan shillings—the cost of a simple meal, a mobile phone airtime scratch card, or the ubiquitous street-side ‘Rolex’.

This is not merely corruption; it is the systemic, calculated commercialisation of citizenship itself. It represents the most profound disconnect between the political class and the people, reducing the grand vision of self-determination to a momentary alleviation of hunger. This crisis, where a nation’s future is bartered for a temporary fix, reveals a political economy built not on service, but on exploitation.

The anatomy of this betrayal can be understood through three devastating layers:

1. The Transaction of Desperation

To simply condemn the voter for this transaction is to profoundly misunderstand the reality on the ground. When a mother faces the choice between the abstract concept of ‘democracy’ and the concrete need to buy salt and posho for her children’s evening meal, the system has already failed her. Her decision is not one of greed, but of profound necessity. The political class understands this desperation intimately and preys upon it. The adage, “A hungry man cannot appreciate the value of gold,” is their operating principle. By ensuring that a significant portion of the population remains in a perpetual state of economic precarity, they create a market for their political currency. The 5,000-shilling note is not a bribe in the traditional sense; it is a weapon of mass coercion, leveraging poverty to maintain power. The voter, in this context, is not selling their vote; they are being forced to pawn their future to survive the present.

The political class understands this desperation intimately and preys upon it. The adage, “A hungry man cannot appreciate the value of gold,” is their operating principle. By ensuring that a significant portion of the population remains in a perpetual state of economic precarity, they create a market for their political currency. The 5,000-shilling note is not a bribe in the traditional sense; it is a weapon of mass coercion, leveraging poverty to maintain power. The voter, in this context, is not selling their vote; they are being forced to pawn their future to survive the present.2. The Deliberate Devaluation of Sovereignty

This commercialisation is not an accidental byproduct of poverty; it is a deliberate strategy of political control. By reducing the electoral process to a series of petty transactions, the ruling system successfully devalues the very concept of popular sovereignty. It sends a clear, corrosive message: Your power as a citizen is not your inalienable right to shape your government, but a petty commodity to be sold to the highest bidder at a tragically low price.This creates a vicious cycle that entrenches the very system it depends on. The politician who buys votes today has no incentive to govern effectively tomorrow, for their re-election does not depend on their performance, but on their pocketbook. They have not won a mandate; they have purchased a silence. The citizen, having traded their leverage for a momentary benefit, is left with neither accountability nor sustainable improvement, ensuring their desperation—and thus their vulnerability to the same transaction—continues into the next election cycle.

3. A Revolutionary Path: From Petty Commerce to Collective Power

The leftist and revolutionary response to this crisis is not to scold the people for their choices, but to attack the conditions that make such a devastating trade seem rational. It is to recognise that the solution lies not in moralising, but in organising.The answer to the 5,000-shilling note is not a plea for integrity, but the construction of a counter-power of collective self-reliance. This means:

Building Economic Autonomy from the Ground Up: The most powerful defiance to this system is to make communities less dependent on the political handouts. This means forming community-owned cooperative farms that feed the people, creating savings and credit schemes that free them from usurious lenders, and establishing community-controlled enterprises that keep wealth within the locality. When people are not hungry, the value of the ‘Rolex’ bribe evaporates.

Reclaiming the Meaning of the Vote: This involves a grassroots political education that reframes the vote not as an individual commodity, but as a collective expression of power. It is to organise people’s assemblies where communities deliberate and agree on a common agenda before any politician arrives. The message to the candidate then becomes: “We will not sell our votes for your chicken and salt. You will earn our collective endorsement by committing, in writing, to deliver on our community’s stated priorities.”

Replacing Transaction with Solidarity: This model kills the politics of the individual handout and replaces it with the politics of the collective good. It asserts that our strength does not lie in the few coins we can extract from a politician, but in the unbreakable bonds of mutual aid we build with our neighbours. It is the understanding that a community that builds a water source together has achieved something infinitely more valuable than what any single voter could ever be paid.

The ‘Rolex for a vote’ is the ultimate symbol of a system that holds the people in contempt. To defeat it, we must refuse its logic entirely. We must build a Uganda where the people are so economically resilient and politically organised that their sovereignty is not for sale at any price, because they have finally understood its priceless value. It is a call to stop being customers in our own political auction and to become the architects of our own collective destiny.

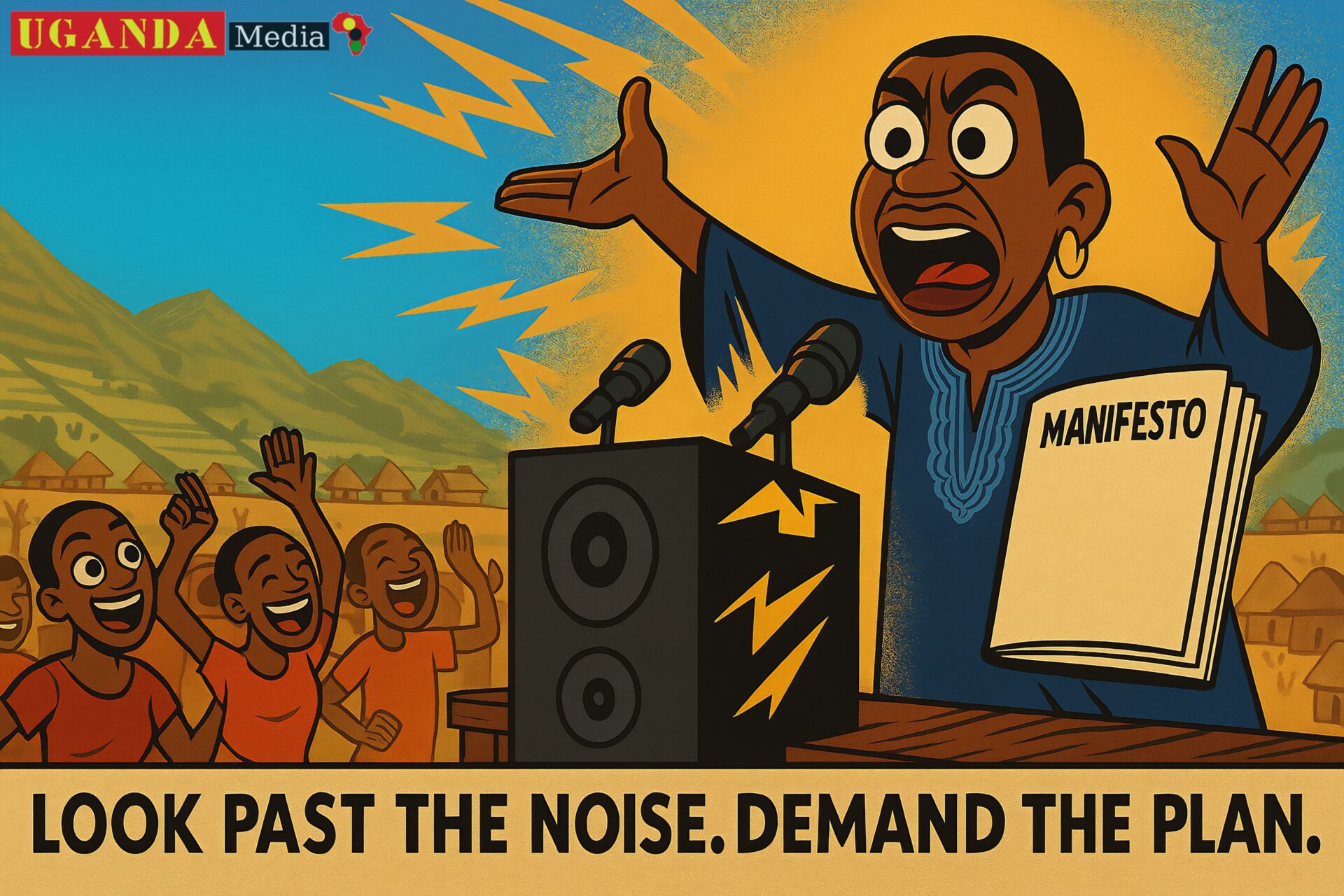

The ‘Rolex for a vote’ is the ultimate symbol of a system that holds the people in contempt. To defeat it, we must refuse its logic entirely. We must build a Uganda where the people are so economically resilient and politically organised that their sovereignty is not for sale at any price, because they have finally understood its priceless value. It is a call to stop being customers in our own political auction and to become the architects of our own collective destiny.The Loud Drum and the Silent Message: How Political Spectacle Replaces Democratic Substance in Uganda

In the vibrant, pulsating heart of a Ugandan political rally, all the senses are engaged. The thunderous bass of a powerful sound system vibrates through the ground, the colourful sea of branded t-shirts and banners dazzles the eye, and the rhythmic, hypnotic chants of the crowd fill the air. It is a masterfully orchestrated spectacle of power, unity, and celebration. Yet, if one listens closely for the message amidst the noise, they often find only an echo. This is the politics of Spectacle Over Substance, a deliberate strategy where the theatrical performance of power systematically replaces the tedious, but essential, work of democratic engagement and policy scrutiny.

The political rally, in this context, is not a forum for deliberation. It is a carefully choreographed ritual designed to generate emotion, project strength, and bypass the cognitive faculties of the citizenry entirely. It is the political equivalent of a sugar rush—intense, energising, but ultimately devoid of nutritional value for the body politic.

This triumph of spectacle rests on three core pillars:

1. The Sensory Overload: Drowning Out Deliberation

The structure of the modern rally is engineered to prevent, not promote, thoughtful engagement. The sequence is telling: hours of musical performances by popular artists, rhythmic chanting led by hired cheerleaders, and long, repetitive introductions by a succession of speakers. By the time the principal candidate arrives, the crowd is exhausted, euphoric, and emotionally charged.When the candidate finally speaks, the format is itself a barrier to substance. The speech is a series of slogans, attacks on opponents, and grandiose, un-costed promises, punctuated by deliberate pauses for the crowd to erupt in cheers. There is no space for a citizen to stand and ask, “But how will you pay for this?” or “What is your specific plan to fix our collapsing health centre?” The environment is chemically hostile to such questions. As the adage goes, “A loud drum hides a weak message.” The spectacle is the drum, its deafening beat ensuring the poverty of the message remains a secret between the speaker and the few critical minds in the audience.

2. The Cult of Personality and the Death of the Idea

This focus on spectacle serves to elevate the individual leader far above the collective platform. The rally is not about promoting a party’s manifesto; it is about performing the strength, popularity, and inevitability of the candidate. The crowd is not there to assess policies, but to witness and partake in the aura of the leader. This creates a political culture where loyalty is to a person, not to a set of principles or a plan for the nation. It dismantles the very idea of accountable governance, for one cannot rationally debate with a personality cult. You are either a believer or a traitor. The spectacle thus becomes a tool for depoliticisation, transforming citizens from critical stakeholders into adoring fans, and politics from a process of collective problem-solving into a form of entertainment and tribal allegiance.

This creates a political culture where loyalty is to a person, not to a set of principles or a plan for the nation. It dismantles the very idea of accountable governance, for one cannot rationally debate with a personality cult. You are either a believer or a traitor. The spectacle thus becomes a tool for depoliticisation, transforming citizens from critical stakeholders into adoring fans, and politics from a process of collective problem-solving into a form of entertainment and tribal allegiance.3. A Radical Reclamation: From Passive Audience to Active Assemblies

Confronted with this empty spectacle, the leftist and revolutionary response is not to try to shout louder within the same format. It is to reject the stage and the audience dynamic altogether, and to build an entirely different model of political conversation.This means a conscious shift:

From the Rally to the Assembly: Instead of gathering in a field to be spoken at, the radical alternative is to gather in a community hall, under a tree, or in a cooperative meeting room to speak with each other. These are spaces for popular assemblies where the agenda is set by the people, not by a central committee.

From Spectator to Participant: In these assemblies, there are no stars and no audience. Every person has a voice. The discussion centres on their immediate, material needs—the cost of seeds, the absence of a midwife at the health centre, the exploitative prices of the middlemen for their coffee. This is politics rooted in the concrete, not the abstract spectacle.

Creating a Counter-Spectacle of Solidarity: The true spectacle that can defeat the empty one is the powerful image of a community working collectively. The sight of neighbours collectively digging a communal water channel, of a farmers’ cooperative successfully bargaining for a better price, or of a community literacy programme graduating its first class—these are the authentic displays of power. They represent a people who are far too busy building their own world to be mesmerised by a politician’s performance.

The spectacle of the rally is designed to make you feel small and the leader large. The task of a genuine people’s politics is to reverse this entirely. It is to understand that our power was never in the noise we make for others, but in the quiet, determined conversations we have among ourselves. It is to turn our backs on the carnival and return to the council, to dissolve the audience and reconstitute the sovereign assembly. The future of Uganda will not be written on the banners of a rally, but in the meeting minutes of a thousand community assemblies, where the people, finally, are the only speakers that matter.

The Harvest of Stones: The Political Economy of Broken Promises in Uganda

In the fertile political landscape of Uganda, a bitter and recurring crop is sown each election cycle: the grandiose, on-the-spot pledge. It is a practice as predictable as the seasons, where a visiting candidate, swept up in the fervour of the rally, promises to restock cattle in Lango, to build a factory in Busoga, or to tarmac a road in Kigezi. These are not the costed, deliberative policies of a manifesto, but political lightning strikes—spectacular, immediate, and utterly disconnected from any plan for sustained growth. This is the Empty Promise Cycle, a sophisticated mechanism of political control that cultivates hope only to harvest despair, ensuring a population remains perpetually dependent on the benevolence of its rulers.

This cycle is not a failure of planning; it is the very essence of a political strategy designed to maintain power through the management of disappointment rather than the delivery of development. It functions through three distinct phases:

This cycle is not a failure of planning; it is the very essence of a political strategy designed to maintain power through the management of disappointment rather than the delivery of development. It functions through three distinct phases:1. The Theatre of Immediacy and the Illusion of Connection

The power of the empty promise lies in its theatricality. It is delivered not from a bureaucratic desk in Kampala, but from the heart of the community, often in response to a staged or genuine plea. This creates a powerful, albeit false, sense of direct connection and empathetic leadership. The candidate presents themselves not as a distant administrator, but as a benevolent patron, capable of cutting through red tape with a single word.This theatre bypasses rational scrutiny. There is no feasibility study, no line in the national budget, and no implementation timeline. The promise exists in the emotional realm, a gift from the leader to the people. As the piercing adage goes, “A promise is a comfort to a fool.” The system is designed to offer this comfort, this immediate emotional payoff, in lieu of the slower, more complex satisfaction of genuine, planned development. The crowd cheers not for a policy, but for a miracle, and at that moment, their critical faculties are surrendered.

2. The Strategic Anatomy of the Unfulfilled Pledge

The emptiness of the promise is not an oversight; it is a calculated feature. A pledge made without a budgetary framework is a debt that was never intended to be paid. Its value is purely electoral and momentary. Once the votes are counted, the promise joins a long and crowded graveyard of similar commitments.This creates a corrosive political logic:

The Absence of Accountability: How can one be held accountable for a promise that was never grounded in a formal plan? The failure is reframed as a “delay,” a “funding shortfall,” or a “priority reassessment,” never as a betrayal.

The Perpetuation of Dependency: The cycle ensures that communities remain in a state of hopeful anticipation. Having received the promise, they now wait for its fulfilment, their political energy focused on reminding the leader of their word rather than on building their own autonomous capacity. They are transformed into supplicants, forever waiting at the gate of the statehouse for the patronage they were promised.

The Weaponisation of Hope: Hope, in this context, becomes a tool for pacification. It is easier to manage a population that is waiting for a promised future than one that is actively building its own present. The constant cycle of promise and disappointment breeds a cynical resignation, a feeling that real change is impossible, and that the best one can do is align with the powerful to receive occasional crumbs.

3. Breaking the Cycle: From Patronage to People’s Power

The leftist and revolutionary response to this cycle is a fundamental rejection of the entire patron-client relationship it reinforces. It is to recognise that freedom lies not in getting the powerful to keep their promises, but in making their promises irrelevant.This requires a radical shift in strategy:

Building Autonomy, Not Appealing to Patrons: The solution to the lack of cattle in Lango is not to beg a politician for a restocking programme. It is for the communities to form pastoralist cooperatives to manage their own herds, pool their resources for veterinary services, and create community-owned seed banks and grazing lands. It is to build an economic reality so resilient that a politician’s promise is seen for what it is: an empty gesture.

Creating a Culture of Concrete Action: This philosophy champions direct action over petition. If a road is needed, the community organises to fill the worst potholes collectively, simultaneously meeting an immediate need and demonstrating their own capacity. This act of self-reliance is a more powerful political statement than any cheer for a promise. It is the people telling the state, “We do not need your charity; we demand the resources that are rightfully ours, and we will manage them ourselves.”

Replacing Hope with Solidarity: The empty promise sells the hope of individual salvation. The radical alternative is to build the concrete reality of collective power. The security of a community that provides for itself through mutual aid is infinitely more valuable than the fragile hope placed in a leader’s word.

The Empty Promise Cycle is a tool that keeps Uganda in a state of political childhood. Breaking it requires a collective coming of age—a conscious decision to stop waiting for a saviour and to begin the difficult, dignified work of building our own future, from the ground up. It is to understand that the most valuable promises are not those made by politicians on a stage, but the ones we make to each other in our communities: to cooperate, to share, and to stand together in unbreakable solidarity.

The Foundation Before the House: The Revolutionary Logic of ‘Freedom First’

In the crowded marketplace of Ugandan political ideas, where parties compete with ever-more detailed catalogues of promises, the People’s Front for Freedom (PFF) presents a stark and radical alternative. Their platform, distilled into the potent slogan “Freedom First,” constitutes a fundamental paradigm shift. It argues that debating policy minutiae under the current system is not just futile, but a dangerous distraction. It is like arguing over the colour of the curtains in a house built on a foundation of quicksand. Before one can discuss the furniture, one must first secure the very ground upon which the house stands.

This philosophy posits that the primary, overriding issue in Uganda is not a lack of specific policies, but the existence of a suffocating, centralized, and oppressive political system that makes the implementation of any truly people-centred policy impossible. Therefore, the first and only meaningful political objective must be the collective liberation of the people from this system itself.

The “Freedom First” framework can be understood through its three revolutionary pillars:

1. The Prerequisite of Liberation

The PFF’s core argument is that there can be no meaningful development, no equitable service delivery, and no social justice without first achieving political and economic emancipation. A manifesto promising better schools is meaningless if the state apparatus is used to arrest teachers who demand better pay. A pledge to build health centres is hollow if the budget for them is systematically looted by an unaccountable patronage network. This approach reframes the political struggle. It is no longer about who can best manage the existing system, but about who is committed to dismantling it and building something new. As the adage goes, “You cannot repair a broken roof while the house is still on fire.” The PFF contends that the entire Ugandan political edifice is ablaze with the fires of oppression and corruption, and the only logical first step is to put out the fire. All other tasks are secondary. This is a direct challenge to the politics of survivalism, insisting that people must fight for sovereignty before they can negotiate for services.

This approach reframes the political struggle. It is no longer about who can best manage the existing system, but about who is committed to dismantling it and building something new. As the adage goes, “You cannot repair a broken roof while the house is still on fire.” The PFF contends that the entire Ugandan political edifice is ablaze with the fires of oppression and corruption, and the only logical first step is to put out the fire. All other tasks are secondary. This is a direct challenge to the politics of survivalism, insisting that people must fight for sovereignty before they can negotiate for services.2. Regional Governance as Anti-Colonial Praxis

The advocacy for a radical shift to regional-based governance is not merely an administrative proposal; it is presented as a form of decolonisation. The current highly centralized state in Kampala is framed as a direct descendant of the colonial model, designed for extraction and control, not for empowerment and service. It is a system that disenfranchises communities from their own resources and destinies.The PFF’s model is a direct assault on this structure. It calls for a return to a governance model that recognises the historic, cultural, and economic realities of Uganda’s constituent parts—the 16 regions that originally negotiated the nation’s founding.

Resource Sovereignty: Under this model, the wealth generated from a region’s resources—whether it is marble from Karamoja, coffee from Bugisu, or tourism from Kigezi—would be primarily managed and utilised for the development of that region. This breaks the cycle where local resources are siphoned to the centre, only to be returned as political patronage.

Cultural and Political Autonomy: It allows for diverse communities to govern themselves according to their own unique social fabrics and priorities, ending the imposition of a one-size-fits-all model from a distant capital. This is a vision of unity through voluntary association, not through forced assimilation.

3. “Freedom First” as a Pathway to People’s Power