The Unspoken Truth: Thirty Years of a Constitution That Never Was

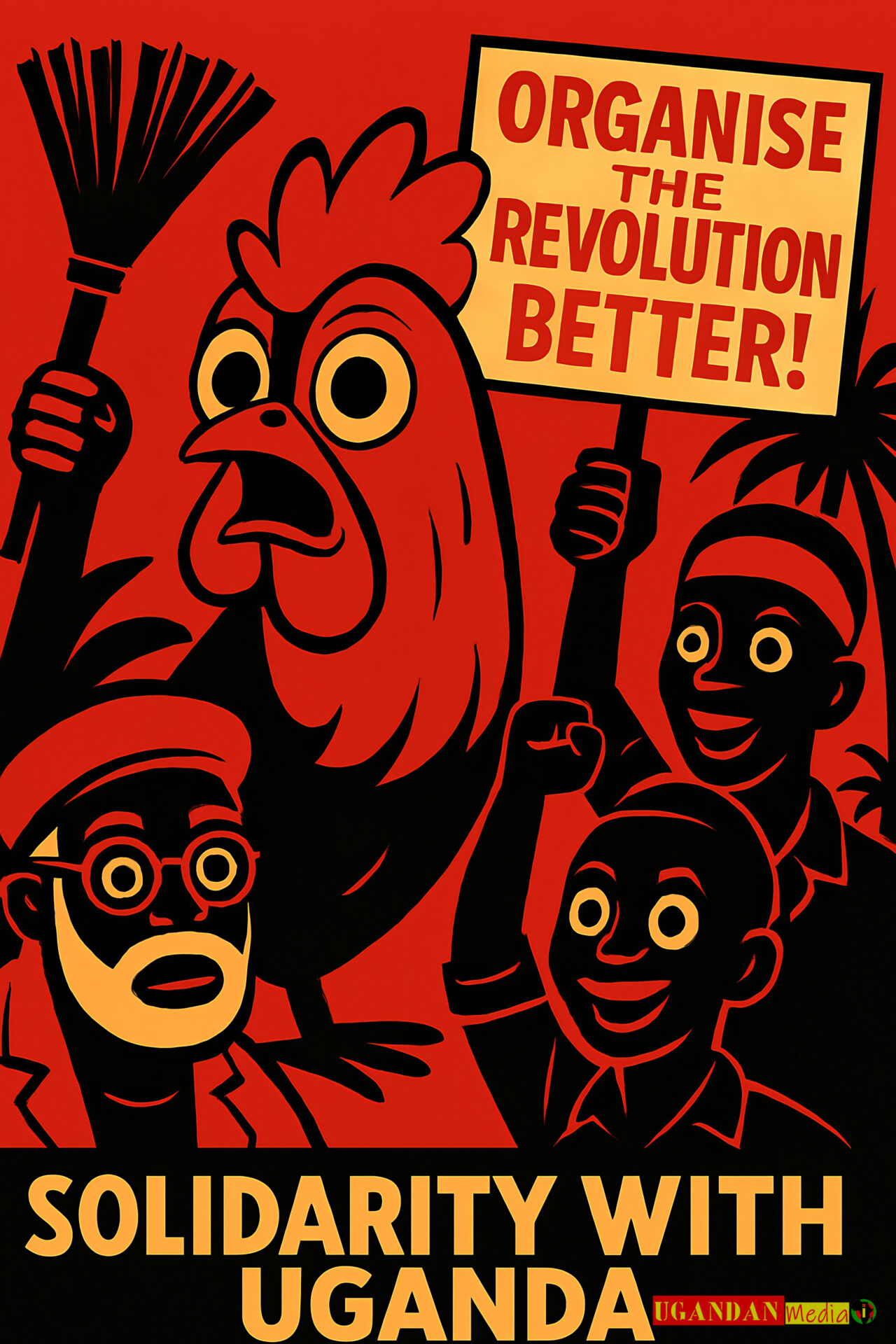

Marking its 30-year anniversary, Uganda’s 1995 Constitution was heralded as a cornerstone for a new, democratic era. But three decades on, a critical question demands an answer: has this document delivered on its promise of a just, free, and stable society? In this incisive analysis, we move beyond celebratory rhetoric to confront the uncomfortable truths exposed by a distinguished panel on Civic Space TV’s Focus on Parliament. Featuring insights from historian Professor Mwambusya, lawyer Sarah Anjo of FIDA Uganda, and social commentator Ernest Taan, this article argues that the constitution functions not as a shield for the people, but as a mirage—a masterpiece of illusion that centralises power rather than limiting it. We dissect how Parliament acts as a mere approval chamber, how justice becomes a commodity for the powerful, and how the state’s hypocrisy fuels a system requiring subjects, not citizens. Ultimately, we look beyond the failing structures of the state to explore a radical vision already taking root: the power of Ugandan communities in Kasese, Bududa, and beyond, who through mutual aid, direct action, and organic solidarity, are building a future of genuine self-governance.

This is not just a critique; it is a call to recognise that the seed of a truly free Uganda grows not in the halls of power in Kampala, but in the everyday cooperation of its people.Marking its 30-year anniversary, Uganda’s 1995 Constitution was heralded as a cornerstone for a new, democratic era. But three decades on, a critical question demands an answer: has this document delivered on its promise of a just, free, and stable society? In this incisive analysis, we move beyond celebratory rhetoric to confront the uncomfortable truths exposed by a distinguished panel on Civic Space TV’s Focus on Parliament. Featuring insights from historian Professor Mwambusya, lawyer Sarah Anjo of FIDA Uganda, and social commentator Ernest Taan, this article argues that the constitution functions not as a shield for the people, but as a mirage—a masterpiece of illusion that centralises power rather than limiting it. We dissect how Parliament acts as a mere approval chamber, how justice becomes a commodity for the powerful, and how the state’s hypocrisy fuels a system requiring subjects, not citizens. Ultimately, we look beyond the failing structures of the state to explore a radical vision already taking root: the power of Ugandan communities in Kasese, Bududa, and beyond, who through mutual aid, direct action, and organic solidarity, are building a future of genuine self-governance. This is not just a critique; it is a call to recognise that the seed of a truly free Uganda grows not in the halls of power in Kampala, but in the everyday cooperation of its people.

Here are 20 key points that explore this radical re-imagining, moving beyond the panellists’ critique to a more fundamental conclusion.

The Constitution as a Mirage: The Grand Illusion of 1995

There is an old adage that speaks a profound truth: “The law is a spider’s web; the small are caught, the great tear it up.” Nowhere is this wisdom more vividly brought to life than in the story of Uganda’s 1995 Constitution. Hailed as a rebirth, a definitive break from a painful past, it was instead a masterpiece of political theatre. It was not designed as a tool for popular empowerment, but as a sophisticated mechanism of control, expertly crafted to give the appearance of freedom while meticulously preserving the architecture of state power. It is, in essence, a mirage—a shimmering vision of water that evaporates the closer one tries to drink from it.

The document’s grandeur lies in its promises. Its pages are filled with the language of liberty, equality, and justice. It guarantees the right to life, to property, to free speech, and to political participation. On paper, it is a formidable shield for the common person against the potential tyranny of the state. This is the illusion, the shimmering surface of the mirage. The fatal flaw, the dry earth beneath, is the deliberate absence of any meaningful mechanism to enforce these rights against a state determined to ignore them.

1. The Architecture of Power, Not Limitation.

A genuine constitution’s primary role is to limit the power of the government, to place it in a cage of clear rules and independent oversight. The 1995 document, however, does the opposite. It centralises power. It creates a system where all meaningful authority flows upwards, to the executive, leaving the legislature and judiciary as decorative pillars—impressive to look at, but bearing no real structural weight. The state, therefore, is not bound by the constitution; it merely uses the constitution’s own clauses to legitimise its actions. When Parliament amends the very foundation of the rule of law—such as removing presidential term limits—it does so using the procedures within the constitution. The system is designed to be self-perpetuating, immune to the very checks and balances it professes to hold dear.

2. Rights as Promises, Not Entitlements.

The Bill of Rights is not a list of enforceable entitlements; it is a list of aspirations, conditional upon the state’s goodwill. For the small-scale farmer in Mbale facing land-grabbing by a well-connected individual, the constitutional right to property is meaningless when the police and courts are instruments of the powerful. For the market vendor in Kikuubo whose stall is demolished without due process, the right to a fair hearing is a cruel joke. The state holds a monopoly on the interpretation and enforcement of these rights. It is, as the adage suggests, the great force that can tear through the web of law with impunity, while the ordinary citizen remains tragically entangled within it.

3. The Purpose: Pacification over Participation.

This design was not an accident. It was a calculated strategy of pacification. After years of conflict, the state offered the constitution as a symbol of peace and normalcy. It was a way to channel popular discontent into endless, fruitless legalisms—to encourage people to petition the state for their rights rather than to claim them through direct action. It teaches a lesson of dependency: “Your freedom is something we grant you, according to our procedures and our timeline.” This disempowers people from the start, convincing them that their primary role is to wait for the state to act, rather than to organise and act for themselves. It replaces the energy of grassroots mobilisation with the passive hope of a favourable court ruling that may never come.

The Alternative: Looking Beyond the Mirage.

The radical conclusion, then, is not to demand a better constitution or more honest leaders to uphold the current one. That is like asking the architect of a prison to design a more comfortable cage. The solution is to recognise the mirage for what it is and to turn our attention to the real, living sources of order and solidarity that exist outside the state’s control.

Our strength has always been in our communities—in the village assemblies that settle disputes, the informal savings groups (esusu) that provide capital, and the kinship networks that offer support in times of crisis. These are forms of social organisation built on mutual aid and consent, not on coercion and hierarchy. They are organic, responsive, and truly accountable. When a community collectively defends a wetland from illegal drainage, it is exercising a sovereignty far more authentic than any parliamentary decree. When a neighbourhood forms a watch group to ensure its own security, it is creating a form of justice that the state’s police force often fails to deliver.

The 1995 Constitution remains a powerful symbol, but its power is that of a sedative. It encourages us to believe that our destiny is tied to documents and distant institutions in Kampala. True empowerment begins when we see past this illusion and invest our energy in building power from the ground up—in our villages, our markets, and our neighbourhoods. It begins when we stop asking the spider for fairness and start weaving our own, stronger webs of community and mutual defence.

2. The Liberation Lie: From Freedom Fighters to the New Palace Guard

There is a piercing adage that cuts to the heart of the matter: “He who fights with monsters should be careful lest he thereby become a monster.” For decades, this truth has played out on the Ugandan stage with the grim predictability of a tragedy. The narrative is seductive: a brave band of liberators emerges from the bush, having toppled a tyrant, vowing to cleanse the nation of the very ills they suffered. They speak of fundamental change, of a people’s government, of a future where power finally serves the many. This is the Liberation Lie. It is not merely a broken promise; it is an inevitable, almost mechanical, transformation where the liberator, upon seizing the state, must necessarily become the new overlord.

The panel’s identification of an “entitlement mentality” within the National Resistance Movement (NRM) is not just an observation about one group’s arrogance. It is the uncovering of a core law of power: the belief that victory in conflict confers not just the right to govern, but a kind of divine and perpetual ownership over the nation itself. The struggle itself becomes the justification for eternal rule.

1. The Seizure of Legitimacy.

The first move of the successful liberation movement is to rewrite the nation’s story. The state is no longer a shared institution belonging to all citizens; it is presented as a prize won through the sacrifice of the liberators. This sacrifice—the lives lost in the bush, the years of hardship—becomes a permanent moral debt that the population is told it can never fully repay. This creates a perverse form of legitimacy. It is not derived from the ongoing consent of the governed, as would be the case in a free association of people, but from a single, historical event. The state, therefore, owes its existence to the movement, not the people to the state. This inversion is the seed of tyranny.

2. The State as a Tool of Reward and Punishment.

Having framed the state as their rightful prize, the liberators then transform its institutions into instruments for managing their coalition. Ministries, security agencies, and public contracts are no longer neutral organs for public service; they become the “spoils of war” to be distributed amongst loyalists. This creates a ruling class whose privilege is directly tied to the survival of the liberation government. To challenge the government is not merely to disagree with a policy; it is to threaten the entire network of patronage, to be ungrateful for the liberation itself. This is why dissent is so often framed not as political opposition, but as a personal betrayal or an attempt to return the country to the “dark days” of the past.

3. The Myth of the “Correct Line”.

Every entrenched power system needs an ideology to justify its permanence. The liberation movement develops this in the concept of the “correct line” or the “only viable path.” They argue that their unique experience in the struggle has granted them an exclusive understanding of the nation’s problems and solutions. Alternative ideas, no matter how popular or rational, are dismissed as the naive prattling of those who “did not fight” or the dangerous schemes of “saboteurs.” This mentality fossilises the ruling group. It prevents renewal, stifles innovation, and blocks the natural, organic evolution of a society’s governance. The liberators, who once embodied change, become the most significant barrier to it.

The Radical Alternative: Power Remains with the People.

The critical flaw is the very act of seizing the central state. The belief that a better world can be built by capturing the same oppressive machinery that you fought against is the Liberation Lie’s greatest trick. The alternative is to recognise that true, lasting liberation cannot be handed down from a palace in Kampala; it must be built from the ground up, in a way that makes centralised overlordship impossible.

This means fostering a society where power is never delegated away entirely. It looks like:

Community-Based Defence: Instead of a national army loyal to a single commander, imagine community-controlled security councils, where local people who know the terrain and the community protect their own neighbourhoods, accountable to those they serve on a daily basis.

Direct Resource Management: Instead of resources flowing to a central treasury to be redistributed as patronage, imagine communities in the Albertine Graben or the mining areas of Karamoja having direct control over their natural wealth, negotiating with traders and investors as equals, not as subjects begging for a share from a distant capital.

The Lukiko as a Living Institution: The traditional Buganda Lukiko (council) and similar structures across other cultures offer a model of discussion and consensus-building that is far more authentic than a rubber-stamp parliament. The goal would be to revitalise these as genuine, rotating assemblies of everyday people, making decisions on matters that affect their immediate lives.

The lesson of the Liberation Lie is that we must stop looking for heroes to capture the state on our behalf. The only liberation that endures is one where the people never relinquish their power in the first place. It is a slower, more complex path, built on the stubborn belief that a million small, self-governed communities are infinitely stronger and more resilient than a single, gilded palace surrounded by walls. It is to understand that the only way to avoid becoming the monster is to refuse to enter its cave altogether.

3. The Myth of the Three Arms: The Puppeteer and His Dolls

There is a wisdom, passed down through generations, that warns us: “When one dancer pays the piper and calls the tune, you do not have three artists; you have one master and his instruments.” This simple truth lays bare the grand deception at the heart of the Ugandan state: the myth of the separation of powers. We are taught from our earliest school days that the Executive, the Legislature, and the Judiciary are independent pillars, each balancing the other to prevent tyranny. This is not just an innocent fairy tale; it is a carefully crafted fiction designed to mask a far more brutal reality. In practice, these three arms are not separate; they are a single, fused mechanism, a hydra with one brain, dedicated solely to its own preservation. This is not a flaw in the system’s design. It is the system working precisely as intended.

The recent panel discussion revealed this in stark relief. Parliament does not check the Executive; it legitimises its edicts. The Judiciary does not impartially interpret the law; it bends it to serve the interests of power. To see this as a corruption of a pure system is to miss the point entirely. The system was never designed to be pure; it was designed to be controlled.

1. The Illusion of Independence.

The concept of separation relies on a willingness by each branch to limit its own power—a notion that defies the very nature of hierarchical institutions. In Uganda, the Executive holds the purse strings, controls public appointments, and, crucially, commands the ultimate instruments of coercion. To expect a Member of Parliament or a judge to act “independently” against an entity that can end their career, or worse, is not just naive; it is to ignore the fundamental dynamics of power. The piper who pays the piper will always call the tune. The occasional, theatrical display of conflict—a parliamentary committee summoning a minister, a court ruling against a minor official—is merely political theatre, a safety valve to sustain the illusion of accountability while the core of power remains untouched.

2. The Fusion for Self-Preservation.

These three arms are fused not by accident, but by a shared interest in maintaining the status quo that privileges them. The MP’s lucrative career, the judge’s elevated status, and the minister’s vast authority all depend on the continued existence and dominance of the central state apparatus. They are not rivals; they are shareholders in the same enterprise. When the state faces a genuine threat to its power—for instance, from a popular grassroot movement—the fusion becomes instantly visible. Parliament will rush through Draconian laws, the police will enforce them brutally, and the courts will validate them in the name of “national security.” The three arms act in concert, revealing themselves as a single, unified fist to crush dissent.

3. The Deliberate Distraction.

This myth serves a crucial purpose: it channels popular discontent into dead ends. When people are wronged, they are encouraged to “go to court” or “lobby their MP,” pathways that are time-consuming, expensive, and ultimately controlled by the very system that caused the grievance. This process exhausts communities, drains their resources, and teaches them a lesson of helplessness. It convinces them that change must always be begged for from the top down, within the rules set by the powerful. It is a brilliant strategy for neutralising opposition, turning energy and anger into futile, endless petitioning.

The Radical Reality: Power is Organic, Not Institutional.

The alternative is to reject the myth entirely and recognise that true, accountable power does not—and cannot—flow from these artificial, centralised institutions. It arises organically from the daily lives and direct interactions of people.

Imagine a different Uganda:

Community Tribunals: Instead of distant, expensive, and often corrupt courts, disputes in a village in Kigezi or a neighbourhood in Arua could be settled by respected elders and rotating community members. Justice would be swift, local, and based on restoring communal harmony, not on punishing transgressions against a distant state’s law.

People’s Assemblies: Instead of a Parliament in Kampala that votes to remove term limits against the will of the people, imagine regular town hall meetings in Fort Portal or Gulu where residents themselves debate and decide on issues affecting their water, their roads, and their schools. The people making the decisions are the ones living with the consequences.

Rotating Delegates, Not Career Politicians: Instead of a permanent political class, communities could select delegates for specific tasks—like negotiating with a neighbouring district over a resource—with a clear mandate and for a limited time. Power would be a temporary responsibility, not a lifelong career.

The myth of the three arms is a cage for our political imagination. It forces us to believe that governance can only look one way. Breaking free means recognising that the most effective forms of social organisation are those we already practice in our families, our savings circles (esusu), and our community work groups. It is to see that the mighty, fused power of the state is, in fact, a fragile illusion when confronted with the determined, self-governing power of a people who have decided to manage their own affairs. The three arms are not pillars holding up the nation; they are chains binding it. And chains, as history shows, are made to be broken.

4. Parliament is an Approval Chamber: The Theatre of Consent

There is a piercing adage that resonates from the villages of Teso to the hills of Kigezi: “When the goat is invited to the leopard’s feast, it is not to dine, but to be the main course.” No institution embodies this grim truth more perfectly than the Ugandan Parliament. We are taught to call it the “People’s House,” a sacred space where representatives gather to debate and shape the nation’s destiny. This is a profound misnomer. In reality, Parliament functions not as a house of the people, but as an Approval Chamber for the Executive. Its primary role is not to legislate in the public interest, but to provide a democratic-looking stamp on pre-ordained decisions, laundering raw state power into the respectable currency of “law.”

The removal of presidential term limits and the age limit were not aberrations; they were the institution performing its true function with brutal clarity. It is not a flawed parliament; it is a parliament flawlessly serving the system it was designed to uphold.

1. The Architecture of Rubber-Stamping.

The process is a meticulously crafted ritual. A government bill, often drafted in the shadows of State House, is presented to Parliament as a fait accompli. What follows is not a genuine debate between competing visions for the country, but a theatrical performance. Backbench MPs may grandstand for their constituents, opposition members may deliver fiery speeches for the cameras, but the outcome is rarely in doubt. The whip system, the distribution of patronage, and the unspoken understanding of consequences ensure that when the vote is called, the Executive’s will prevails. The debate is not a means to an outcome; it is a spectacle designed to create the illusion of deliberation, to make the eventual rubber-stamping appear legitimate. The goat is allowed to bleat in protest before the feast proceeds.

2. Laundering Violence into Law.

This is Parliament’s most insidious function: it transforms repression into legislation. When the state wishes to stifle dissent, it does not simply send out the police to break up gatherings arbitrarily. Instead, it instructs its majority in Parliament to pass a “Public Order Management Act.” This law then gives a legalistic veneer to the suppression of assembly. The violence of the state is no longer naked aggression; it is “law enforcement.” Similarly, when the state wishes to control digital speech, it doesn’t just block websites; it passes a “Computer Misuse Act.” By moving repression from the realm of arbitrary power to the realm of statute, Parliament makes resistance seem like lawlessness. It forces citizens to defy not just a government, but “the law of the land,” a psychologically much heavier barrier. Parliament acts as the state’s laundry, washing the stains of authoritarianism in the detergent of legal procedure.

3. The Neutralisation of Dissent.

Parliament’s very existence serves to channel popular discontent into a harmless cul-de-sac. When a community in the Albertine Graben is suffering from environmental degradation caused by a state-backed oil project, they are told to “let your MP raise it in Parliament.” This process absorbs the energy of the protest. It turns a urgent grassroots demand into a parliamentary question that may be filed, a committee meeting that may be postponed, or a report that will gather dust. The people are pacified, waiting for a saviour from Kampala who is part of the very system exploiting them. Parliament thus becomes a key tool in disempowering communities, teaching them to look upwards for solutions rather than relying on their own collective power.

The Radical Alternative: Power in the Parish, Not the Palace.

The solution is not to elect “better” MPs. The problem is the very idea that a small group of people in a distant city can or should have the power to make life-and-death decisions for millions across the country. The alternative is to reclaim the power we have delegated.

This means building a society where:

Decision-Making is Hyper-Local: Imagine if the budget for a community’s borehole or feeder road was not debated and disbursed by officials in Kampala, but was decided upon by the people of the parish or village in a public assembly. The decision-makers are present, accountable, and directly affected by the outcome.

Recallable Delegates, Not Career Politicians: Instead of electing an MP for five years to a lavish life in the capital, communities could select mandated delegates for specific tasks—to liaise with neighbouring districts on a shared issue, for example. These delegates would have no permanent power; they would be recallable at any moment if they failed to represent the community’s will.

The Lukiko as a Living Model: The traditional Buganda Lukiko and similar councils across cultures offer a glimpse of a more organic, discussion-based form of governance. Revitalising these as genuine, rotating assemblies of community members could replace the need for a centralised, partisan parliament.

The Ugandan Parliament is not a symbol of democracy; it is a monument to its absence. It is the stage where the people’s sovereignty is ritually sacrificed. True freedom will not come from storming this chamber, but from turning our backs on it entirely, and instead, building real, direct, and accountable power in our own communities. The goat’s only hope is to stop attending the leopard’s feast and to build its own pasture, guarded by the community itself.

5. The Army in Parliament: The Unblinking Eye at the Feast

There is an adage, sharp as a panga blade, that has echoed across our hills for generations: “The hunter who must bring his spear into the negotiation hut is not there to talk; he is there to dictate the terms.” The presence of ten uniformed representatives of the Uganda People’s Defence Forces (UPDF) in our Parliament is often dismissed as a curious anomaly, a peculiar holdover from a different time. This is a dangerous misreading. It is not an anomaly; it is the most honest confession the state ever makes. It is a blunt, unvarnished statement of a fundamental truth: the ultimate authority of the Ugandan state does not rest on the consent of the governed, the wisdom of the law, or the integrity of the constitution. It rests, finally and unequivocally, on the threat of organised force.

These ten officers are not MPs in any meaningful sense. They are a permanent, sitting reminder that every law passed, every budget approved, and every debate held in that chamber does so under the unblinking gaze of the institution that holds the monopoly on violence. They are the spear in the negotiation hut.

1. A Symbol of the True Foundation of Power.

The entire edifice of the state—the constitution, the courts, the presidency—is presented as the source of authority. But this is a carefully maintained fiction. The UPDF in Parliament exposes the reality: these institutions are superstructure. The foundation is the military. Their presence demonstrates that the state understands that its survival is not guaranteed by popular support, but by its ability to deter and crush challengers. The law is not sovereign; the army that can enforce or ignore the law is sovereign. This makes a mockery of the concept of civilian rule. It inverts the proper order, placing the servants of the state—the military, whose duty is to protect the people—above their masters.

2. The Function of a “Listening Post”.

The justification for their presence—that they act as a “listening post”—is a chillingly accurate description of their role. A listening post in military terms is an advanced position for gathering intelligence on an enemy. By describing the army’s role in this way, the state openly admits that it views the democratic process itself as a potential battlefield. The officers are not there to contribute to debate; they are there to monitor, to assess loyalties, and to report on any signs of dissent that might threaten the core power structure. This has a profound, chilling effect. How freely can an MP speak truth to power when the very embodiment of that power is sitting across the aisle, taking notes? It is a system of institutionalised intimidation.

3. The Laundering of Military Authority into Civilian Law.

When Parliament votes on a deeply unpopular law, the presence of the UPDF delegates performs a crucial function: it launders military authority into the appearance of civilian consensus. The vote count includes their ten voices. Thus, a law that is fundamentally upheld by the threat of force is made to look like the product of democratic deliberation. This merges the power of the gun with the legitimacy of the ballot, creating a hybrid system where the state can claim a democratic mandate while resting on authoritarian foundations. It is the ultimate political deception.

The Radical Alternative: Defence by the Community, For the Community.

If the presence of the army in Parliament symbolises a state that rules by threatening its people, the alternative is to build a society where security is a function of the community, not a weapon of the state.

This means re-imagining security from the ground up:

Community Defence Councils: Instead of a national army loyal to a commander-in-chief in Kampala, imagine security managed at the village and parish level. Rotating groups of community-nominated individuals, known and trusted by everyone, could be responsible for local safety. Their authority would come from the community they serve, and their accountability would be direct and immediate. They would protect people, not power.

The End of Monopolised Force: A centralised army is primarily a tool for projecting power externally and maintaining control internally. A decentralised model of community-based defence makes the very idea of a military coup or the use of soldiers against civilians logistically impossible. There is no single army to hijack.

The UPDF as a True People’s Force: In this vision, the UPDF itself could be broken down and integrated into regional defence units, accountable to local assemblies rather than a political centre. This was, ironically, part of the original ten-point programme—a people’s militia, not a praetorian guard for a ruling clique.

The ten officers in Parliament are not a sign of the state’s strength; they are a confession of its profound weakness and insecurity. A system that is truly built on consent does not need to bring its spear to the meeting. It is a sign that the state knows its authority is illegitimate, and that it must constantly remind everyone of the violence that lies beneath the surface.

True security cannot be imposed from above by an institution that views the people as a threat to be managed. It can only grow from below, woven into the fabric of mutual trust and collective responsibility that has always been the real source of resilience for Ugandan communities. The hunter’s spear has no place in the council of equals. The first step towards a free society is to recognise it for what it is, and to begin building a community where such a symbol is rendered obsolete.

6. Justice is a Commodity: The Marketplace of Power

There is an old, bitter adage that circulates in the shadows of our courtrooms: “The scales of justice are weighted not with blindfolded lead, but with the gold of the powerful.” This sentiment captures a truth that the vulnerable and the poor understand intimately. The law, for all its grand language of impartiality and blind fairness, is not a sacred principle dispensed from on high. It is a commodity—a thing to be bought, sold, and interpreted in a marketplace where the currency is power, connection, and wealth. As the lawyer on the panel observed, the courtroom is not a temple of equity; for the marginalised, it is often the final chamber where state-sanctioned inequality is rubber-stamped and given the cold, formal seal of legitimacy.

The promise of equal justice under the law is the state’s most potent myth. It convinces the dispossessed that the system that oppresses them will also, miraculously, be the instrument of their liberation. This is the cruellest trick of all.

1. The Architecture of a Pay-to-Win System.

From the moment a case is filed, justice is a transaction. There are court fees to pay, lawyers to hire, and often, unofficial “facilitation” costs to ensure a file does not get lost, or a hearing is not postponed indefinitely. For a wealthy land-grabber seeking to evict a community from ancestral land, these are minor business expenses. For the community itself, pooling money for a single lawyer might take years of savings. The system is engineered from the start to favour those with capital. The law is not a shield for the weak; it is a weapon that the strong are better equipped to wield. The quality of your justice is directly proportional to the depth of your pockets.

2. Interpretation Through the Lens of Power.

The law is not a set of fixed, immutable rules. It is a fluid text, and its meaning is determined by those who interpret it. Judges, prosecutors, and police officers do not operate in a vacuum; they are part of the same state hierarchy and are susceptible to its political winds and social prejudices. A law against “common nuisance” can be used to silence a dissenting voice in a town hall meeting. A law on “idle and disorderly” persons can be used to harass a market vendor who cannot afford a licence. For a woman seeking a share of matrimonial property after a separation, the law’s strict requirements for proof of contribution can become an insurmountable wall, especially when her husband, with greater resources, can hire a battery of lawyers to exploit every technicality. The law is not neutral; it bends to the weight of social and political power.

3. The Courtroom as a Tool of Pacification.

The justice system serves a crucial political function: it channels raw injustice into a slow, expensive, and confusing process that exhausts and demoralises people. When a factory pollutes a river, poisoning a community’s water source, the people are told to “sue the company.” This transforms their righteous anger into a labyrinthine legal battle that can last a generation. The community’s energy is drained, its resources spent, and its focus diverted from direct action. The system teaches a lesson: your grievance is not a matter of right and wrong, but a complex technical issue to be handled by experts. By the time a judgement is delivered—if it ever is—the community may be broken, and the victory hollow. The courtroom becomes where struggles go to die, not where justice is born.

The Radical Alternative: Justice as a Social Bond, Not a State Service.

The alternative is to reject the idea that justice must be a service provided by a distant, hostile state. Instead, we must recognise that real justice is a social bond, rooted in community, restoration, and mutual accountability.

This means reviving and re-imagining traditional, decentralised forms of conflict resolution:

Community Restorative Circles: Imagine a dispute over land or marital property being resolved not by a stranger in a wig, but by a circle of respected elders, family members, and peers from the village. The goal would not be to “win” a case or punish, but to restore harmony, find a solution that the community can live with, and reintegrate the individuals involved. This is the spirit of many traditional justice systems, focused on healing rather than retribution.

Women’s Solidarity Networks: To counter the systemic bias against women, imagine networks of women providing their own support: collectives of experienced advocates (not necessarily state-licensed lawyers) who can guide others through separation, offer safe harbour, and use collective pressure to ensure fair treatment outside the formal, patriarchal court system.

Direct Accountability: In cases of harm, the community itself could oversee processes of restitution and reconciliation, ensuring that the offender directly addresses the harm caused to the victim and the community, rather than simply being processed by an impersonal prison system.

The state’s legal system is not broken; it is working perfectly as a tool of social control. True justice will not be found in a better-funded court or a more progressive judge. It will be found when we stop looking to the state’s marketplace and start building our own forms of conflict resolution based on the simple, radical idea that people, when organised freely and equally, are capable of creating their own fairness. It is to understand that the scales of justice will only be balanced when we, the people, take them out of the hands of the merchants of power and hold them ourselves.

7. Rights are Not Given, They are Taken: The Illusion of the Gifted Freedom

There is a formidable adage whispered in the villages when discussing the powerful: “You do not beg for a share of the harvest from the man who stole your granary.” This simple, piercing truth strikes at the heart of one of the state’s most carefully cultivated myths: that our rights and freedoms are gifts, generously granted to us by the constitution and the government of the day. This is a dangerous delusion, a pacifying fantasy designed to keep us in a permanent state of supplication. The reality is that rights are not bestowed from above; they are inherent to our humanity, and history shows they are only ever secured and defended through collective action, courage, and defiance.

The belief that the state is the source of our rights is the ultimate political deception. It transforms us from sovereign individuals into grateful subjects, forever indebted to our rulers for privileges they can just as easily take away.

1. The State as Gatekeeper, Not Benefactor.

Imagine a guard who locks a community away from a freshwater spring, then periodically dispenses small cups of water, claiming to be their benefactor. This is the state’s relationship to our rights. The right to speak freely, to assemble, to own the fruits of our labour—these are not inventions of the state. They are the natural conditions for a free and dignified life. The state, however, positions itself as the gatekeeper. It writes down these inherent rights in a document, and then, with breathtaking arrogance, presents itself as the entity that has “given” them to us. This allows it to act as the perpetual gatekeeper, defining the terms, setting the limits, and revoking the “gift” whenever it feels threatened. The removal of presidential term limits is a classic example: a right of the people to choose new leadership was treated as a privilege that the state could withdraw.

2. The Historical Record: Every Right is Written in Struggle.

Look at any right we now take for granted, and you will find a story of people taking it, not waiting for it to be given. The right to land? It was not granted by a benevolent colonial officer; it was fought for by communities defending their ancestral territories, sometimes with their lives. The right of market vendors to trade without brutal harassment? It is maintained daily by their collective refusal to be cowed, by their networks of solidarity that withstand the rates collector’s threats. When a community in a mining area organises to demand a fair share of resource revenue, they are not invoking a state-given right; they are enacting an inherent one through their collective strength. The state may later codify these victories into law, but only to claim credit and to regulate the very power it failed to suppress.

3. The Psychology of Defiance vs. the Pathology of Permission.

Believing that rights are given creates a psychology of dependency and fear. It teaches people to ask politely, to lobby, to petition—to approach the state as a child approaches a strict parent. This mindset is disempowering by design. In contrast, understanding that rights are taken fosters a psychology of defiance and self-reliance. It shifts the question from “What will the state allow us to do?” to “What are we, as a community, capable of achieving together?” This is the spirit behind the successful resistance of a village against a land grabber, where the community’s sheer unity and resolve becomes its greatest weapon, far more potent than any court injunction they might later seek to legitimise their victory.

The Radical Path: Building Power, Not Begging for Permits.

The alternative is to turn our energy away from the state and towards each other, to build the collective power that makes claiming our rights a reality.

This means:

Creating Facts on the Ground: Instead of begging the local council for a clean water source, a community can collectively pool resources, dig a protected well, and manage it themselves. They have then taken their right to water. The state’s role becomes irrelevant.

Solidarity as a Shield: When a farmer’s crops are threatened with destruction by a corrupt official, the arrival of hundreds of fellow farmers from neighbouring villages to stand with them is a more powerful defence than any lawyer. This collective action takes the right to security and property.

Ignoring to Nullify: When a repressive law is passed to stifle assembly, the most effective response can be to organise gatherings anyway, in such numbers and with such social backing that the law becomes unenforceable. This is how rights are taken back—by rendering the state’s authority null and void through mass non-compliance.

The constitution’s Bill of Rights is not a charter of liberty; it is an inventory of what the state claims to own and dole out. True freedom will never be found in its pages. It will be forged in the stubborn solidarity of a community protecting its land, in the collective voice of a people speaking truth to power, and in the unwavering understanding that our dignity is not a favour to be granted, but a power to be asserted. We must stop begging at the gate of the granary and, instead, reclaim the fields that are rightfully ours.

8. The Failure of ‘Citizen Agency’ Within the System: The Birdcage of Controlled Participation

There is a poignant adage that speaks to this very dilemma: “You cannot teach a bird to fly inside a cage, no matter how large you paint the sky on the walls.” The professor’s call for “citizen agency” is a noble and intellectually sound prescription. It suggests that the solution to our political paralysis lies in citizens awakening, organising, and holding power to account. Yet, this call rings hollow because it ignores the fundamental nature of the cage. How can citizen agency function when the state, with meticulous precision, systematically dismantles, co-opts, or corrupts every single independent structure—be it civil society, the media, or political opposition—that might serve as a platform for such agency? The problem is not a lack of will among the people, but the fact that the system is deliberately engineered to make genuine, effective citizen action impossible.

The state is not a passive arena; it is an active participant that designs the rules of the game to ensure it can never lose. Calling for citizen agency within this system is like urging a farmer to grow crops on a concrete slab.

1. The Systematic Dismantling of Platforms for Agency.

True citizen agency requires independent organisations where people can gather, share ideas, and build collective power. The state recognises this as its greatest threat. Therefore, we see a persistent strategy to neutralise these platforms:

Civil Society: Organisations that advocate for human rights, transparency, or community empowerment are labelled as “foreign agents” or “enemies of development.” Their registration is blocked, their bank accounts frozen, and their leaders subjected to intimidation. The space for organised, non-state activity is deliberately shrunk.

Media: Independent media outlets are burdened with punitive regulations, expensive licensing fees, and the constant threat of closure. Journalists are harassed, and the public narrative is funnelled through outlets friendly to the regime. This strangles the free flow of information essential for citizens to make informed decisions.

Political Opposition: Beyond the usual electoral obstacles, genuine opposition is fragmented through co-option, with promises of patronage luring away its members. It is criminalised through trumped-up charges, and its public gatherings are violently dispersed. The message is clear: political organising outside the official structure will be crushed.

In this environment, “citizen agency” is reduced to a solitary, individual act—a social media post, a whispered complaint—which is easily isolated and ignored. The state ensures there is no runway for citizen power to take off.

2. The Illusion of Participation: The State’s Safety Valve.

The system offers controlled, illusory forms of participation to placate the desire for agency. Public hearings on legislation, invitations to “stakeholder meetings,” and voting in elections are presented as evidence of a functioning democracy. But these are largely theatrical. The outcomes are pre-determined; the consultations are a box-ticking exercise. This is not agency; it is a safety valve designed to release steam without affecting the engine of power. It teaches people that participation means reacting to state initiatives, not initiating their own. It is a way to manage dissent, not to empower it.

3. The Redirection of Energy into Dead Ends.

The most insidious effect is how the system redirects the immense energy and ingenuity of the people into futile channels. Citizens are encouraged to spend their time writing petitions to officials who will not read them, attending court cases that will be adjourned indefinitely, or campaigning for opposition politicians who will be neutralised upon entering Parliament. This process exhausts communities, drains their resources, and fosters cynicism. It is a brilliant mechanism for ensuring that popular energy is wasted on activities that pose no real threat to the core power structure.

The Radical Alternative: Agency Through Autonomy.

The solution, therefore, is not to try harder within the cage. It is to stop recognising the cage’s authority and to build agency entirely outside of it. Real citizen agency is not about influencing the state; it is about making the state irrelevant to daily life.

This means:

Building Parallel Systems: Instead of begging the state for services, communities can build their own. This could mean creating community-owned water projects, setting up neighbourhood watch groups for security, or forming cooperatives to market agricultural produce directly, bypassing exploitative middlemen. This is practical agency.

Ignoring the State’s Rules: When a local council imposes a punitive tax on small traders, the most powerful form of agency can be collective non-compliance. When hundreds of vendors simply refuse to pay, supported by their own solidarity network, they exercise real power.

The Power of the Esusu and the Village Assembly: The traditional savings circle (esusu) and the village meeting are pure forms of citizen agency. People pool their resources and make decisions without waiting for permission from Kampala. Strengthening these hyper-local, self-managed institutions is the foundation of a power that the state cannot easily reach or break.

The professor’s call for citizen agency fails because it addresses the bird and not the cage. True agency will not be found in reforming the state’s institutions, but in building our own. It is the quiet, determined work of a community managing its own affairs, providing for its own needs, and defending its own members. It is the understanding that our power does not lie in how loudly we can shout at the palace gates, but in how well we can build our own house, on our own land, governed by our own rules. The bird must first realise that the cage door is already open if it simply decides to stop believing in the walls.

9. We Are Not Citizens, We Are Subjects: The Architecture of Submission

There is a formidable adage that has survived through generations of our elders: “The hunter only tells the lion that the forest belongs to everyone when the lion is in a cage.” This wisdom cuts to the heart of our political reality. The most acute observation from the panel was the distinction between a citizen and a subject. A citizen is a sovereign participant, an equal co-owner of the society, with the inherent power to shape its rules and hold its managers to account. A subject, in contrast, is one who obeys. The Ugandan state, in its design and daily operation, does not require citizens. It requires, cultivates, and enforces a nation of subjects.

This is not an accident of poor governance. It is the deliberate outcome of a system built not on a social contract of equals, but on a hierarchy of command and control, where power flows only downward and obedience is the primary civic duty.

1. The Constitutional Illusion of Citizenship.

The 1995 Constitution, on the surface, proclaims the sovereignty of the people. It uses the language of citizenship, but its mechanisms are designed for subjecthood. The power it ostensibly grants is immediately delegated away to distant representatives and state institutions, with no tangible way for the people to recall it. We are taught that our role is to vote every five years and then return to a state of quiet obedience, waiting for the state to act upon us. This is the relationship of a subject to a monarch, not of a citizen to a servant government. The state presents itself as the benevolent provider of rights and services, and in doing so, frames our participation as grateful receipt, not empowered claim.

2. The Machinery of Subject-Creation.

The state actively manufactures subjects through several interlocking systems:

The Militarisation of Public Life: The presence of the army in Parliament and the pervasive role of security agencies in civilian affairs send an unambiguous message: the ultimate authority is force. This teaches people that their safety is not a right they possess, but a conditional gift granted by the state, which can be withdrawn at any moment. A subject lives in fear; a citizen lives in confidence.

Economic Dependency: By centralising control over resources and livelihoods, the state makes itself the primary source of employment, contracts, and favours. This creates a population that must be obedient to access economic survival. You do not bite the hand that (claims to) feed you. This economic dependency is a powerful tool for eroding the autonomy that defines a citizen.

The Demeaning Ritual of Petitioning: From seeking a birth certificate to challenging a land grab, people are forced into a posture of supplication. They must approach local councils, government offices, and police stations as beggars, not as rights-holders. This constant ritual of kneeling before authority, both literally and figuratively, reinforces a subject mentality.

3. The Symptoms of Subjecthood in Daily Life.

The evidence of our subject status is all around us. It is in the silence that falls over a taxi when a police roadblock is sighted. It is in the resigned acceptance of a teacher who has not received a salary for months, yet dares not protest too loudly. It is in the farmer who watches a bulldozer destroy his crops on the orders of a ‘investor’ with state connections, believing he has no recourse. This is not passivity; it is a rational response to a system that has demonstrated, time and again, that initiative and defiance will be punished. The state has not failed to create citizens; it has spectacularly succeeded in creating subjects.

The Radical Reclamation: From Subjects to Community Sovereigns.

The path out of subjecthood does not lie in appealing to the state to treat us better. It lies in a collective act of rediscovery: remembering that we are the true sovereigns and beginning to act like it.

This means:

Replacing Permission with Initiative: Instead of waiting for a government permit to build a community well, the community builds it. Instead of begging the police for protection, a neighbourhood establishes its own watch based on mutual responsibility. Each act of self-provision is a declaration of citizenship.

Creating Parallel Legitimacy: The power of a community managing its own affairs—settling disputes through elders’ councils, managing a village savings fund, organising collective farming—creates a source of legitimacy that rivals that of the state. This is where real citizenship is born: in the practice of self-rule.

Withdrawing Consent: The power of the state is a myth that persists only as long as we act as if it is real. When a critical mass of people simply stop believing in its authority—when they stop obeying unjust laws, stop fearing its agents, and stop looking to it for solutions—the illusion shatters. The lion realizes the cage door is open.

The Ugandan state calls us citizens, but it treats us as subjects. Our freedom will not be found in trying to reform this relationship, but in ending it. It lies in the profound realisation that the forest does, in fact, belong to everyone. It is time to stop listening to the hunter and to step out of the cage, not as obedient subjects, but as the true sovereigns of our own lives and communities.

10. Patriarchy is the State’s Ally: The Twin Pillars of Control

There is an adage, sharpened by generations of women’s whispered wisdom: “The same hand that rocks the cradle to give life is the first to be slapped down when it reaches for power.” This truth reveals a fundamental alliance that structures our society, one so ingrained we often mistake it for nature itself. The systemic disenfranchisement of women is not merely a social ill existing alongside state power; it is its indispensable ally. Patriarchy and the state are not separate entities; they are twin systems of hierarchy, control, and violence, each strengthening the other. The subjugation of women in the home and community provides the essential blueprint and training ground for the subjugation of all people by the state.

To understand the state, one must first understand the patriarchal family, for they are cut from the same cloth.

1. A Shared Logic: Hierarchy as Natural Order.

Both systems are founded on the same core lie: that hierarchy is the natural and necessary order of the world. The patriarchal household teaches that the man is the natural head, the final decision-maker, and the owner of property and even of the people within it. This mirrors exactly the state’s doctrine: that a small group of rulers in Kampala are the natural heads of the nation, the final decision-makers, and the ultimate owners of the land and its resources. This logic conditions people from birth to accept domination as inevitable. A child raised to believe a woman’s voice is worth less is being prepared to believe their own voice is worthless before a District Commissioner or a Member of Parliament.

2. The Interlocking Machinery of Control.

The state does not dismantle patriarchy; it codifies and weaponises it. The states’ laws and institutions often reinforce male dominance, creating a powerful feedback loop:

Control of Property and Bodies: When a woman is denied rightful ownership of land she has cultivated for decades because a title deed bears only her husband’s name, the state’s courts often uphold this injustice. This is not a failure of the law; it is the law functioning to maintain an economic hierarchy that benefits the male-headed household, which is a smaller, more manageable unit for the state to control than a truly empowered individual.

The Violence of Enforcement: The threat of violence that enforces a man’s authority in a home is the same principle that enforces the state’s authority. The police who dismiss a report of domestic violence as a “private family matter” are applying the same logic that allows the state to brutalise dissenters—it is the assertion that the powerful have the right to use force to maintain their position. One system of violence legitimises the other.

3. The Political Utility of a Subjugated Half.

A population divided is a population controlled. By upholding patriarchal norms, the state ensures that a vast portion of its potential opposition—women—is pre-occupied with the daily struggle for survival and basic dignity within their own homes. The energy that could be directed towards challenging state corruption is exhausted in battling for a share of the household budget or for the right to make simple decisions. This division is the state’s greatest defence. It is far easier to rule over fragmented, internally conflicted households than it is to face a united community of equals.

The Radical Alternative: Dismantling the Twin Pillars.

The Radical Alternative: Dismantling the Twin Pillars.

The struggle for women’s liberation is therefore not a separate, special interest; it is the frontline of the struggle against all forms of domination. To challenge one is to necessarily challenge the other.

The path forward is to build communities based on the very principles that patriarchy and the state destroy:

Horizontal Solidarity, Not Vertical Power: Imagine community councils where mothers, fathers, the young, and the old have an equal voice, not based on gender or age, but on shared interest. This models a form of decision-making that renders the authoritarian state obsolete.

Economic Autonomy for All: Women’s cooperatives that control their own land, processing, and marketing of crops are not just business ventures; they are acts of defiance. They create economic power structures outside of both patriarchal and state control, proving that resources can be managed collectively and equitably.

Community-Based Defence and Justice: Instead of relying on a police force that mirrors patriarchal violence, communities can develop their own safety networks and restorative justice circles. These would focus on de-escalation, mediation, and community healing, directly challenging the punitive logic of both the state and the patriarchal order.

The state fears the liberated woman for the same reason it fears the liberated community: she has no need for a master. By breaking the hierarchy in the home, we shatter the myth of hierarchy in the nation. The hand that rocks the cradle, when united with other hands in solidarity, has the power not just to reach for power, but to reshape the world into one where no hand need be slapped down again. True freedom will arrive not when women are given a place at the master’s table, but when we together dismantle the table and build a new one, in a new room, where everyone has a seat.

11. Hypocrisy is the State’s Fuel: The Deliberate Double Game

There is an adage, worn smooth by use but never heeded by those in power: “The thief who shouts ‘stop thief!’ the loudest does not want justice; he wants to control the chase.” This captures the essence of the Ugandan state’s enduring strategy. The system’s sustained hypocrisy—its meticulous pretence of democracy while engaging in autocratic rule—is not a sign of confusion or weakness. It is its primary fuel. This double game is not a mistake; it is a sophisticated, deliberate mechanism essential for maintaining a veneer of international legitimacy while simultaneously crushing internal dissent. The state understands that raw, naked power is unstable; power cloaked in the respectable language of law and democracy is far more durable.

This hypocrisy is the glue that holds the entire edifice together, allowing it to speak from both sides of its mouth with calculated precision.

1. The Theatre for International Consumption.

On the world stage, the state performs the role of a democratic government. It points to its constitution, its periodic elections, and its nominal opposition in parliament as proof of its legitimacy. This performance is crucial for accessing international loans, attracting investment, and maintaining diplomatic relations. Donor nations and institutions can turn a blind eye to repression if they can point to a constitutional framework and a ballot box, however compromised. The state’s hypocrisy provides them with the necessary cover. It is a carefully managed brand identity, a democratic façade behind which the real business of control continues uninterrupted. The World Bank can fund a road project because, on paper, Uganda is a democracy, not a dictatorship.

2. The Weapon Against Internal Dissent.

Domestically, this same hypocrisy becomes a powerful weapon. When citizens protest an injustice, the state does not simply deny their right to protest; it uses its own laws to criminalise them. It charges them with “holding an unlawful assembly” under a Public Order Management Act passed by a “democratic” parliament. It tries them in courts that are nominally “independent.” This transforms a clear political conflict into a complex legal debate. The dissenter is no longer a citizen fighting for a right; they are a criminal defying “the law.” This demoralises and confuses opposition. How do you fight a system that uses the language of justice to perpetrate injustice? The state’s hypocrisy allows it to frame resistance as illegality, making the protester an outlaw and the autocrat a guardian of order.

3. The Cultivation of Cynicism and Apathy.

The constant, glaring gap between promise and reality—between the rights in the constitution and the reality of state violence—breeds a deep-seated cynicism among the population. When people are told they live in a democracy but experience a dictatorship, many eventually conclude that all politics is a sham. This apathy is a key goal of state hypocrisy. A population that believes nothing can change, that all leaders are corrupt, and that participation is pointless, is a population that is easy to control. The state’s double game convinces people that the problem is not a specific government, but the very nature of power itself, leading to resignation rather than rebellion.

The Radical Response: Seeing Through the Facade and Building Truth.

The solution is not to plead for the state to be more consistent or honest. That is like asking a leopard to change its spots. The solution is to recognise the hypocrisy for what it is—a deliberate strategy of control—and to render it ineffective.

This requires a two-fold approach:

Naming the Game: The first step is to consistently and publicly expose the contradiction. This means rejecting the state’s own terms. When it speaks of “democracy,” we must point to the army in Parliament. When it speaks of “the rule of law,” we must point to the land grabs committed by its officials. We must refuse to be drawn into its legalistic traps and instead insist on talking about raw power and justice.

Building Authentic Legitimacy: The most powerful response to a hypocritical system is to build authentic, transparent alternatives alongside it. When a community creates its own transparent, accountable council to manage a water project, it demonstrates what real governance looks like. When a women’s cooperative manages its finances with integrity, it shows that hierarchy and corruption are not inevitable. These small, tangible examples of truth and fairness expose the state’s theatre for the hollow performance it is.

The state’s power relies on our willingness to accept its lies. Its hypocrisy is the fuel that runs the engine of control. But fuel can be cut off. By withdrawing our belief in its democratic pretence and by building concrete examples of a better way in our communities, we can drain its tank. The thief can only control the chase if we are chasing the wrong person. It is time to stop chasing the illusions and start building the reality we deserve—one based not on double-talk, but on direct, honest, and collective self-governance.

12. Voting is a Ritual of Powerlessness: The Theatre of the Ballot Box

There is a stark adage that circulates among those who have seen the machinery of power from the inside: “When you are allowed to choose the colour of the rope that binds you, you are not being freed; you are being made a partner in your own captivity.” This is the essence of the electoral ritual in Uganda. Elections are not exercises in genuine choice or popular sovereignty; they are carefully managed spectacles, a political theatre designed to create the illusion of participation while meticulously ensuring the core power structure remains untouched. Voting is not an act of power; it is a ceremony of powerlessness, a process that teaches people to place their hopes in a system engineered to betray them.

The state organises this grand theatre every five years not because it believes in the will of the people, but because it understands the psychological utility of the performance.

1. The Illusion of Choice and the Reality of Management.

The ballot paper presents a fiction of options. Yet, the playing field is so profoundly tilted—through control of state resources, the partisan use of the police and army, the dominance of the media space, and the systematic weakening of opposition structures—that the outcome is a foregone conclusion. The campaign rallies, the debates, the posters plastered on every available surface—all this noise and colour serves as a smokescreen for the quiet, unwavering consolidation of power. It is a magician’s trick, directing your attention to the waving hand so you do not see the other hand securing the locks. The people are given a choice between different managers of the same oppressive system, all while the owner of the plantation remains firmly in place.

2. The Ritual’s True Purpose: A Safety Valve for Discontent.

The electoral cycle is the state’s most effective tool for channelling popular frustration into a harmless, predictable ritual. For years, grievances over land grabs, corruption, and unemployment are bottled up. Then, the election season arrives. People are encouraged to vent their anger not through direct action or organised resistance, but by casting a ballot for a different candidate. This process absorbs the energy of dissent, transforms it into a manageable statistic, and provides a cathartic release. Once the votes are counted (or discarded), the state can declare the “people’s will” has been expressed, and demand another five years of quiet obedience. The ritual provides a controlled explosion of political energy, preventing a more uncontrollable blaze.

3. The Delegation of Power and the Erosion of Agency.

At its core, voting is an act of surrendering power. It is based on the idea that for the next five years, the citizen’s role is to hand over their agency to a representative who will (theoretically) act on their behalf. This teaches a lesson of dependency and passivity. It tells people that their role in shaping society is limited to a single day every half-decade, and that for the intervening period, they are merely spectators. This disempowers communities, convincing them that complex problems must be solved in Kampala, rather than by their own collective intelligence and action at the village or parish level. It is the ultimate act of political disenfranchisement, disguised as its opposite.

The Radical Alternative: Power in the People’s Assembly, Not the Ballot Box.

The alternative to this ritual of powerlessness is not to seek a “freer and fairer” election. It is to reject the premise that real power can be handed over to a representative in a faraway city. True power is built and exercised directly, every day.

This means shifting our energy from the spectacle of voting to the quiet, steady work of building autonomy:

Ignore the Theatre, Build the Real: Instead of expending all energy on a five-yearly electoral circus, that same effort can be directed towards creating permanent, local institutions of self-rule. A community that meets regularly in a people’s assembly to manage its water source, its security, and its disputes is practising a form of democracy that is direct, immediate, and meaningful.

Withhold Consent: The most powerful response to a managed election is mass non-participation or, more radically, the creation of parallel systems of legitimacy. When a community resolves its issues through its own council and ignores the decrees of a state-appointed official, it is voting with its feet in the most profound way possible.

Direct Action Over Delegated Pleas: Rather than voting for a candidate who promises to address an issue with the National Water and Sewerage Corporation, a community can organise to repair its own well and manage it collectively. This is a direct seizure of power and responsibility.

The ballot box is a cage designed to make us feel free. True freedom will not be found in choosing a new master every five years, but in the courageous decision to have no masters at all. It lies in turning our backs on the theatre of the state and turning towards each other, to build a society where power is not a thing to be given away in a ritual, but a shared responsibility to be exercised by all, every single day. The real vote does not happen with ink and paper; it happens with our hands, our minds, and our collective will to build a world beyond the state’s charming illusions.

13. The ‘Grassroots’ are Bought with Rice and Sugar: The Commerce of Consent

There is an adage that has never lost its sting: “When the river is thirsty, it will accept water even from a poisoned well.” This speaks to the desperate calculus of survival, a calculation the Ugandan state understands with cold precision. The panel’s observation that public consultations are tokenistic scratches the surface of a deeper, more cynical strategy. This is the state’s preferred method of engagement: reducing profound political discourse about the future of our communities, our land, and our lives to a simple, demeaning transaction. It is the process of selling our collective future for a bag of sugar, a kilo of rice, or a few crumpled banknotes. This is not consultation; it is the commerce of consent, a deliberate strategy to commodify our political will and purchase our silence cheaply.

The state is not incompetent at hearing the people; it is brilliantly effective at ensuring the people have nothing meaningful to say when it is “listening.”

1. The Theatre of Participation.

The ritual is familiar. A minister or official arrives in a village with great fanfare. A meeting is convened. The community’s immediate, crushing needs—the failed borehole, the impassable road, the crumbling school—are laid bare. The official listens sympathetically, then offers a “solution”: a token gift of food aid, a promise to “look into it,” and a distribution of small amounts of money for “transport” or “lunch.” The profound, systemic issues of land rights, resource allocation, and political marginalisation are deftly sidelined. The conversation is steered away from justice and towards charity. The meeting concludes with a photo opportunity, and the official departs, having transformed a potential political challenge into a successful public relations event. The community is left with a temporary salve for their hunger, but a deepened wound to their autonomy.

2. The Reduction of a Political Voice to a Commodity.

This transaction has a devastating psychological impact. It teaches people that their voice, their opinion, and their consent have a price, and that price is pitifully low. It reduces a citizen’s stake in their nation’s future to the value of a momentary meal. This process breeds a corrosive cynicism, where participation is not about principle or the common good, but about extracting whatever immediate, material benefit one can from the powerful. It turns political engagement into a form of begging. By making the transaction personal—the money handed directly to an individual—it shatters the possibility of collective, principled resistance. Why stand united with your neighbours against a land grab when you can individually receive a bag of sugar to ease your family’s week?

3. The Strategic Cultivation of Dependence.

This is not a flawed system; it is a perfectly designed one. The state is not trying to create empowered, self-reliant communities. It seeks to create dependent subjects. By ensuring that the most necessities are intermittently provided as political favours rather than secured as rights, the state makes itself the centre of survival. This dependency is the bedrock of its control. A population that depends on the state for its next meal cannot afford to challenge that state. The rice and sugar are not gifts; they are the interest payments on a debt of subservience the state forces us to incur.

The Radical Alternative: Reclaiming the Language of Needs as Rights.

The way out of this trap is to refuse the transaction entirely and to rebuild a politics based on collective self-reliance and mutual aid.

This requires a fundamental shift:

Reject the Token, Assert the Right: The most powerful response is to collectively reject the handout. To tell the official: “We do not want your sugar. We want control over the land that grows the sugarcane.” This reframes the struggle from one of supplication to one of sovereignty.

Build Autonomous Welfare: The state’s power to bribe is broken when communities build their own capacity to meet their needs. A village savings and loan association (esusu) that can provide emergency funds is immune to the state’s petty cash. A community-owned grain store undermines the power of a politician’s bag of rice. This builds a foundation of independence from which to speak truth to power.

Transform Charity into Solidarity: Instead of accepting individual handouts, communities can create their own systems of mutual support. If a family’s house burns down, the community collectively rebuilds it, drawing on a tradition of reciprocity that long predates the state. This reinforces bonds of solidarity, whereas state charity destroys them.

The state’s bag of sugar is a poison pill, designed to sweeten our submission. Our future will not be secured by becoming better bargainers in this vile market. It will be secured when we turn away from the poisoned well and dedicate ourselves to digging our own, together. It will be built when we understand that the price of our freedom is not a transaction to be made with our rulers, but a responsibility to be shouldered with our neighbours. True power lies not in what we are given, but in what we can build and defend for ourselves.

14. Our Strength is in Our Communities: The Unseen Republic

There is an adage that carries the weight of generations: “A single stick is easily broken, but a bundle of sticks is unbreakable.” While the state in Kampala performs its hollow theatre of democracy, a different, more resilient Uganda thrives in the shadows of its neglect. In the daily rhythms of life—in the bustling taxi parks, the vibrant markets, and the quiet village gatherings—Ugandans are not waiting for permission to govern their lives. They are practising a pure, organic form of democracy based on mutual aid and bottom-up cooperation. The boda boda savings groups, the market vendor associations, and the village community meetings are not just social clubs; they are the cells of a parallel, unseen republic, proving that our greatest strength has never lain in the state, but in each other.

These organisations are a silent rebuke to the centralised state. They function on principles that the state only pretends to understand: genuine solidarity, direct accountability, and shared interest.

1. The Boda Boda Savings Group: The Economy of Trust.

In a sector ignored by formal banks and exploited by police, boda boda riders have created their own financial system. Their weekly esusu or savings group is a masterpiece of self-organisation. Each member contributes a fixed amount, and the pooled sum is given to one member in rotation. This is not just about money; it is about trust. There is no written contract enforceable by the state’s courts. The agreement is binding because it is rooted in the community. A rider who defaults will find himself ostracised, his reputation ruined. This is a justice system that is swift, fair, and infinitely more effective than the state’s lethargic courts. It demonstrates that complex economic activity can be managed equitably without top-down control.

2. The Market Vendor Association: The Politics of Direct Action.

When a city council authority threatens to demolish stalls or impose crippling new taxes, the market vendors do not first petition their MP. They gather. Their association, led by elected representatives they see every day, organises a collective response. They may negotiate as a bloc, or they may simply collectively refuse to comply. Their power does not come from a constitution; it comes from their unity and their ability to paralyse the local economy. This is direct democracy in action—people facing a common threat, deliberating, and acting in their collective interest. The state’s power stops at the edge of their solidarity.

3. The Village Meeting: The Parliament of the People.

Under the shade of an ancient tree, a village gathers to discuss a common problem: a broken water source, a conflict between families, a threat from a nearby commercial farm. There is no speaker with absolute authority. Elders, women, and youth speak. The goal is not a winner-takes-all vote, but a consensus that everyone can live with. This is the original Lukiko, a form of governance that is ancient and inherently legitimate because every voice is heard. It is the antithesis of the rubber-stamp parliament in Kampala. It resolves conflicts and manages resources with a wisdom and fairness that the state’s distant, corrupt bureaucracy can never achieve.

The Radical Imperative: From Informal Survival to Formal Power.

The tragedy is that we have been taught to see these community structures as merely informal, apolitical, or temporary. We see them as ways to survive the state’s failures, rather than as the blueprint for replacing the state’s functions. The radical opportunity is to recognise these networks for what they are: the foundational units of a free society.

The path forward is to consciously strengthen and connect these cells of the unseen republic:

Political Recognition: The first step is to shift our perspective. We must see the village meeting as a more legitimate parliament than the one in Kampala. We must see the boda boda savings group as a more reliable bank than the state-controlled financial system.

Building a Federation of Communities: Imagine if these community organisations—the farmers’ cooperatives, the market associations, the water user groups—began to federate at a district level. They could form councils that could manage resources, coordinate trade, and provide security based on a network of mutual agreements, making the state’s provincial administration irrelevant.