Twenty Key Points of Analysis

The Illusion of “Unauthorised” Information: Who Owns the Truth in Uganda?

In the cool January air of 2026, as another election cycle tightened its grip on Uganda, the state’s communications regulator issued a seemingly mundane notice. It had blocked a website providing voter location information, deeming it “unauthorised.” This single bureaucratic term, dripping with the cold ink of officialdom, reveals a foundational and dangerous lie upon which the entire edifice of control is built: that the people’s knowledge must be granted permission by the state.

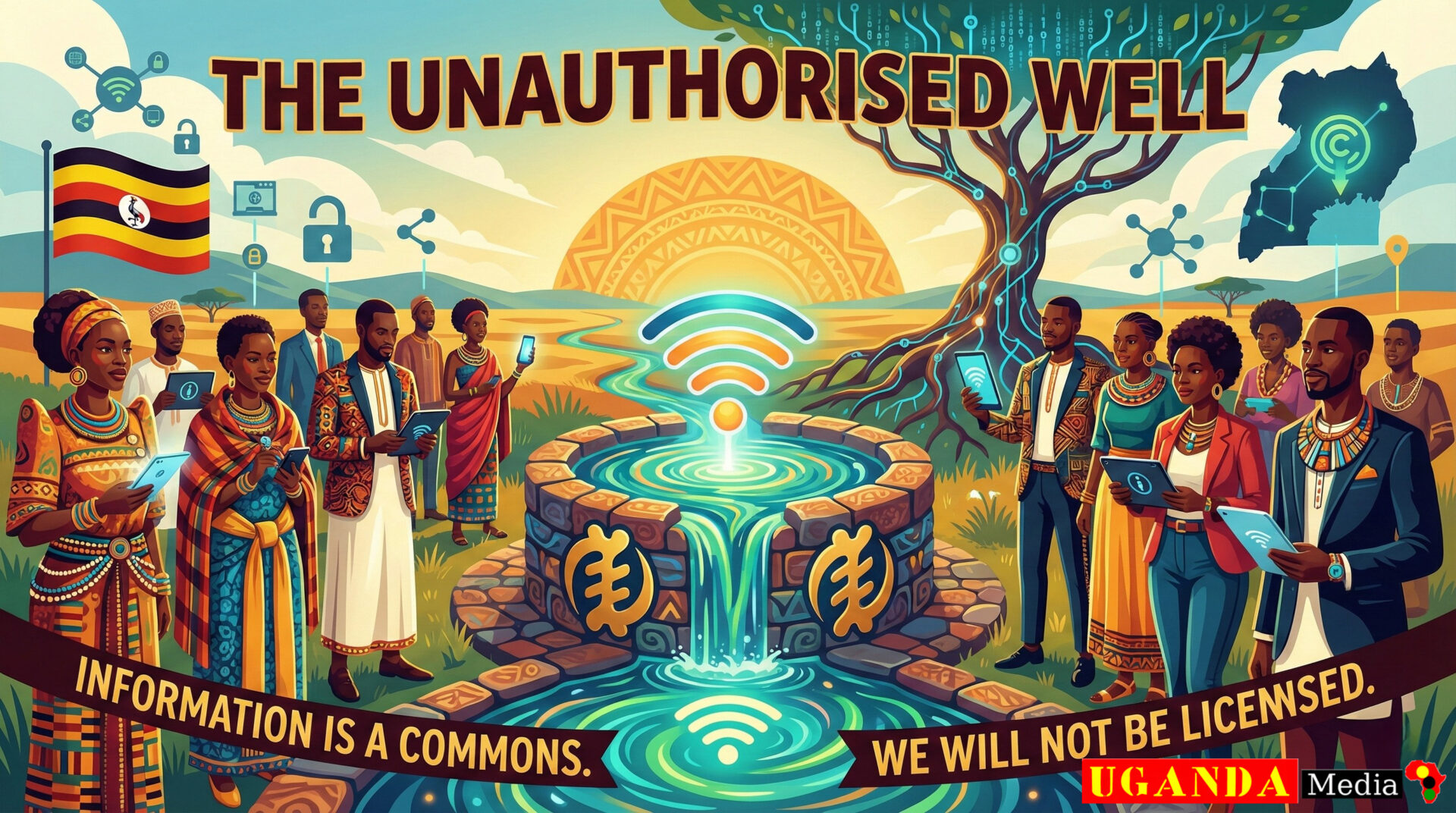

This action frames information not as a common birthright, a shared resource for navigating our collective life, but as a controlled commodity. It operates on the principle that truth itself is subject to licensing, that the facts of our own democracy—where to vote, who is registered—are the exclusive intellectual property of a government department. It is the digital equivalent of a colonial officer declaring a community’s ancestral well “unauthorised” because it wasn’t dug by the Crown’s engineers.

Knowledge as a Commons, Not a Crown Copyright

In a truly free society, information is a commons. Like the air we breathe or the water in a public well, it belongs to everyone. Its value multiplies through sharing, and its accuracy is strengthened through collective verification by an engaged populace. Think of the age-old practice in Ugandan villages, where elders gather under the omusizi tree to discuss community affairs; knowledge is pooled, stories are cross-referenced, and a shared understanding emerges from the conversation itself. No single elder holds a “licence” to speak. The UCC’s logic would post a guard by the tree to silence anyone not pre-approved by the parish chief.

The regime, personified by the long-reigning dictator Yoweri Museveni, understands this power intimately. For a system built on patronage, myth-making, and the careful curation of reality, the unregulated flow of information is existential kryptonite. An independent website mapping voter locations isn’t a technical nuisance; it is a direct challenge to a core mechanism of power. It suggests that the people can organise, verify, and empower themselves without waiting for a handout of “official” data from the Electoral Commission—a body whose independence has been fatally compromised by decades of executive overreach.

The regime, personified by the long-reigning dictator Yoweri Museveni, understands this power intimately. For a system built on patronage, myth-making, and the careful curation of reality, the unregulated flow of information is existential kryptonite. An independent website mapping voter locations isn’t a technical nuisance; it is a direct challenge to a core mechanism of power. It suggests that the people can organise, verify, and empower themselves without waiting for a handout of “official” data from the Electoral Commission—a body whose independence has been fatally compromised by decades of executive overreach.The Irony of “Protection” and the Reality of Control

The state’s justification—to “prevent the dissemination of misleading information”—is a patronising deceit. It assumes the public are naive children, incapable of discerning truth, who must be fed only pre-chewed, state-sanctioned morsels. This is the logic of every oppressive system in history. As the old adage goes, “A man who locks away the candles fears not the darkness, but what people might see by the light.” The regime does not fear misinformation half as much as it fears any information it does not directly manufacture and distribute.

What if the official register is flawed? What if names are missing from state-approved lists in opposition-leaning areas? A parallel, community-driven platform could expose such “errors,” holding power to account. This is precisely what the state cannot allow. By declaring such projects “unauthorised,” it criminalises transparency itself. It transforms citizen-led accountability into an act of sedition.

This has a chilling, real-world effect. It stifles the ingenuity of Ugandan tech developers who might build tools for civic empowerment. It tells community organisers that their efforts to inform their neighbours are illegal. It centralises all trust in institutions that have repeatedly betrayed it, forcing people to rely on the very authorities accused of manipulating the process.

Beyond the Ballot: A Fight for Cognitive Liberty

The battle over this voter website is a microcosm of a far larger struggle. It is not merely about an election logistics page; it is about who controls the narrative of Ugandan life. From economic data and public health statistics to historical education and news reporting, the principle of “authorisation” is a tool to keep society in a state of managed ignorance.

Ultimately, the claim to control information is a claim to control people. A populace that can freely share, debate, and verify information is a populace that cannot be easily led or misled. It is a populace that can build its own systems of mutual aid and solidarity, independent of the state’s corroded structures. The regime’s frantic need to stamp “UNAUTHORISED” on any source of knowledge it does not command is the clearest possible admission of its own weakness. It is the fear of a system that knows its legitimacy is so brittle that it cannot withstand the simple, unregulated act of people talking to each other, sharing what they know, and discovering their own collective power. The truth, much like the will of the people, does not require a permission slip from the Uganda Communications Commission to exist.

Ultimately, the claim to control information is a claim to control people. A populace that can freely share, debate, and verify information is a populace that cannot be easily led or misled. It is a populace that can build its own systems of mutual aid and solidarity, independent of the state’s corroded structures. The regime’s frantic need to stamp “UNAUTHORISED” on any source of knowledge it does not command is the clearest possible admission of its own weakness. It is the fear of a system that knows its legitimacy is so brittle that it cannot withstand the simple, unregulated act of people talking to each other, sharing what they know, and discovering their own collective power. The truth, much like the will of the people, does not require a permission slip from the Uganda Communications Commission to exist.Creating a Monopoly on Truth: The State’s “Exclusive” Right to Reality in Uganda

The Uganda Communications Commission’s statement that “the management of voter registration data… remains the exclusive constitutional responsibility of the Electoral Commission” is not a neutral description of administrative protocol. It is a declaration of intellectual sovereignty. It asserts that the fundamental facts of democratic participation—who is eligible to vote, and where—are not a public resource, but the copyrighted property of the state. This enforces a monopoly on truth, and in a system where the regulator, the Electoral Commission, and the executive are widely perceived as limbs of the same political body, this monopoly has a single beneficiary: the regime of dictator Yoweri Museveni.

The Mechanics of the Monopoly

An enforced monopoly works by outlawing competition. By decreeing the Electoral Commission (EC) as the sole legitimate source of voter data, the state criminalises any parallel, community-driven effort to collect, verify, or share that same information. It is the equivalent of a government declaring itself the only legal cartographer, then distributing maps with certain villages and roads mysteriously omitted. The power lies not in providing a perfect service, but in being the only one allowed to provide any service at all.

This is profoundly anti-democratic. Democracy, at its core, is a system of public verification. It relies on the ability of citizens to check, challenge, and confirm the processes that govern them. A state monopoly on electoral data deliberately breaks this mechanism. It tells the public: “You must trust the product, and you are forbidden from inspecting the factory.” When that factory—the EC—has been under the stewardship of the same political establishment for decades, its operational independence fatally compromised by patronage and pressure, this demand for blind faith is not about integrity; it is about impunity.

This is profoundly anti-democratic. Democracy, at its core, is a system of public verification. It relies on the ability of citizens to check, challenge, and confirm the processes that govern them. A state monopoly on electoral data deliberately breaks this mechanism. It tells the public: “You must trust the product, and you are forbidden from inspecting the factory.” When that factory—the EC—has been under the stewardship of the same political establishment for decades, its operational independence fatally compromised by patronage and pressure, this demand for blind faith is not about integrity; it is about impunity.Shaping Reality to Fit the Fiction

The purpose of this monopoly is not to ensure accuracy, but to control the narrative. It grants the regime the exclusive power to define reality. If the EC’s register is flawed—if names are missing in regions perceived as unsympathetic to the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM)—there can be no legally sanctioned, independent audit to prove it. Any website or group that attempts to compile its own data becomes, by definition, “unauthorised” and illegal. Thus, the state’s version of events becomes the only version permitted to exist. Discrepancies are not corrected; they are erased by statute.

This creates a perverse incentive. The institution tasked with administering a fair contest is protected from any meaningful public scrutiny of its foundational work. Its performance cannot be measured against any independent standard, because it has outlawed the creation of such standards. This is the ultimate conflict of interest, institutionalised. As the old adage goes, “He who makes the measure will never find himself short.” The regime, through its control of the EC, holds the official ruler. It alone gets to measure the dimensions of the democratic playing field, and it assures us—with the full force of the law—that the field is perfectly level, whether it is or not.

The Social and Philosophical Cost

Beyond the immediate electoral manipulation, this monopoly on truth attacks the very capacity for a free society to function. It dismantles the principle of collective intelligence—the idea that a community, through open comparison and dialogue, is wiser and more accurate than any single authority. It replaces the vibrant, noisy marketplace of ideas, where facts are tested and honed, with a state-run dispensary distributing pre-packaged information.

It also fosters a culture of enforced gullibility. Citizens are commanded to trust, and then systematically shown why that trust is misplaced. The resulting cynicism is not an accident; it is a tool. A population that believes all sources are equally corrupt or unreliable is a population disarmed, unable to mobilise around a shared, verified truth. The monopoly thus achieves two goals: it shapes the immediate facts on the ground, and it degrades the public’s long-term ability to discern fact from fiction at all.

It also fosters a culture of enforced gullibility. Citizens are commanded to trust, and then systematically shown why that trust is misplaced. The resulting cynicism is not an accident; it is a tool. A population that believes all sources are equally corrupt or unreliable is a population disarmed, unable to mobilise around a shared, verified truth. The monopoly thus achieves two goals: it shapes the immediate facts on the ground, and it degrades the public’s long-term ability to discern fact from fiction at all.Conclusion: Resisting the Single Story

The fight against this information monopoly is, therefore, not a technical squabble over data management. It is a fundamental struggle for cognitive liberty—the right of people to know, to verify, and to understand their own world without a state-appointed intermediary. The regime’s desperate need to brand independent verification as “unauthorised” is a telling admission of weakness. It reveals a power structure so insecure in its own legitimacy that it cannot tolerate the simple act of people comparing notes.

True popular sovereignty begins when the monopoly on truth is broken, and knowledge is returned to the commons, where it belongs—not as a privilege granted by the state, but as a common resource nurtured, shared, and fiercely protected by the people themselves.

True popular sovereignty begins when the monopoly on truth is broken, and knowledge is returned to the commons, where it belongs—not as a privilege granted by the state, but as a common resource nurtured, shared, and fiercely protected by the people themselves.The Pretext of “Misinformation”: A Patronising Dictate Dressed as Protection

When the Uganda Communications Commission justifies its censorship by citing the need to prevent “the dissemination of information that could potentially mislead the public,” it is deploying the most threadbare and authoritarian of cloaks. This pretext, as ancient as tyranny itself, is not a genuine safeguard for an informed citizenry. It is a patronising dictate that serves a singular purpose: to pre-emptively criminalise any narrative, any fact, any perspective that diverges from the official line. It treats the Ugandan people not as sovereign adults capable of reason, but as a naive flock whose thoughts must be shepherded by the state.

The Logic of Paternalistic Control

This framing is profoundly insulting. It assumes a vast, inherent incompetence within the populace. The logic is clear: the public, in its raw state, is too simple, too emotional, too easily duped to be trusted with the unvarnished flow of information. Therefore, a benevolent authority—in this case, the regime of dictator Yoweri Museveni and its organs like the UCC—must act as the stern but caring parent, filtering the world’s complexity, deciding what is suitable for consumption, and withholding what it deems “harmful.” This creates a sanctioned reality, a nursery version of events where difficult truths and challenging questions are tucked away like dangerous tools.

But this is not protection; it is the engineering of ignorance. By monopolising the role of arbiter, the state places itself beyond challenge. Any attempt by journalists, community organisers, or ordinary citizens to present alternative data, to question official statistics, or to offer a different interpretation of events can be instantly smothered under the blanket accusation of spreading “misinformation.” The term becomes a catch-all warrant to silence dissent. As the old adage warns, “Beware the shepherd who is more afraid of the sheep talking to each other than he is of the wolves.” The regime’s excessive fear of “misleading” speech reveals its true anxiety: not external falsehoods, but the internal, collective conversation of the people it rules.

But this is not protection; it is the engineering of ignorance. By monopolising the role of arbiter, the state places itself beyond challenge. Any attempt by journalists, community organisers, or ordinary citizens to present alternative data, to question official statistics, or to offer a different interpretation of events can be instantly smothered under the blanket accusation of spreading “misinformation.” The term becomes a catch-all warrant to silence dissent. As the old adage warns, “Beware the shepherd who is more afraid of the sheep talking to each other than he is of the wolves.” The regime’s excessive fear of “misleading” speech reveals its true anxiety: not external falsehoods, but the internal, collective conversation of the people it rules.The Destruction of Grassroots Epistemology

A healthy society relies on a distributed process of truth-seeking. It involves debate, cross-referencing sources, and the collective wisdom that emerges when communities share, discuss, and verify what they see and experience. In villages across Uganda, from the trading centres of Kasese to the fishing communities on Lake Victoria, people have always practised this. They piece together information from multiple neighbours, from market chatter, from personal observation, to form a practical understanding of their world.

The state’s “misinformation” pretext is a direct assault on this grassroots epistemology. It declares that this organic, horizontal process of verification is illegitimate and dangerous. The only valid fact is the one stamped and approved by the central authority. This criminalises the very act of independent thought and communal fact-checking. A youth using social media to livestream a discrepancy at a polling station, a farmers’ cooperative documenting price collapses contrary to ministry reports, or a neighbourhood WhatsApp group questioning the official cause of a local blackout—all can be recast not as civic engagement, but as purveyors of “misinformation” threatening public order.

The state’s “misinformation” pretext is a direct assault on this grassroots epistemology. It declares that this organic, horizontal process of verification is illegitimate and dangerous. The only valid fact is the one stamped and approved by the central authority. This criminalises the very act of independent thought and communal fact-checking. A youth using social media to livestream a discrepancy at a polling station, a farmers’ cooperative documenting price collapses contrary to ministry reports, or a neighbourhood WhatsApp group questioning the official cause of a local blackout—all can be recast not as civic engagement, but as purveyors of “misinformation” threatening public order.A Smokescreen for the Real Deceit

The cruel irony is that this crusade against so-called misinformation actively enables the greatest deception of all: the illusion of a fair and transparent process. By silencing all competing voices at the source, the regime ensures that its own narrative—however implausible or at odds with observable reality—faces no formal challenge. It creates a sterile information environment where the only “truth” is the one that sustains the existing power structure. The demand for “orderly conduct” becomes a demand for silent compliance.

Ultimately, this pretext exposes the regime’s contempt for the intellectual autonomy of its citizens. It is a strategy of power, not pedagogy. A confident and legitimate government, secure in its record and its popular support, would engage with critics, correct errors openly, and welcome public scrutiny as a strengthening force. A regime that instead rushes to pull the fire alarm of “misinformation” at the first spark of independent reporting or communal coordination confesses its own weakness. It admits that its version of reality is too fragile to survive in the open air of free discussion, and so it must construct a closed, controlled space where only its own voice echoes. The true threat to Uganda is not misinformation from below, but the enforced silence that allows deception from above to reign unchallenged.

Ultimately, this pretext exposes the regime’s contempt for the intellectual autonomy of its citizens. It is a strategy of power, not pedagogy. A confident and legitimate government, secure in its record and its popular support, would engage with critics, correct errors openly, and welcome public scrutiny as a strengthening force. A regime that instead rushes to pull the fire alarm of “misinformation” at the first spark of independent reporting or communal coordination confesses its own weakness. It admits that its version of reality is too fragile to survive in the open air of free discussion, and so it must construct a closed, controlled space where only its own voice echoes. The true threat to Uganda is not misinformation from below, but the enforced silence that allows deception from above to reign unchallenged.From “Preventive” Action to Pre-emptive Repression: The Logic of the Insecure State

When the Uganda Communications Commission describes its silencing of a voter information website as a “purely administrative and preventive” measure, it is using the cool, clinical language of bureaucracy to sanitise an act of raw political control. This framing is deliberate and revealing. It seeks to recast a targeted strike against public knowledge as a routine, almost technical, procedure—akin to repairing a road or updating a ledger. But beneath this veneer of administrative duty lies a far darker and more revealing logic: the logic of pre-emptive repression. It is a doctrine that declares any potential challenge to the state’s authority not merely an offence, but a threat so profound it justifies suppression before it even fully materialises. This is the nervous heartbeat of a security state, not the confident rhythm of a free republic.

The Alchemy of “Prevention”: Turning Possibility into Crime

The term “preventive” performs a subtle but powerful alchemy. It shifts the justification for state violence—for censorship is a form of violence against the collective mind—from a response to a concrete illegal act, to a reaction against a mere possibility. The website in question was not accused of hacking, of fraud, or of inciting immediate violence. Its crime was its potential: the potential to offer an alternative data source, the potential to enable greater public scrutiny, the potential to empower citizens outside official channels. The state, in its self-appointed role as omnipotent seer, claims the right to silence this potential based on its own prophecy of harm.

This transforms civic initiative into a pre-crime. A farmer pooling resources with neighbours to independently monitor crop prices could be considered “preventing” market instability. A community mapping unreliable water sources could be framed as “preventing” social unrest. The principle is infinitely elastic and thus infinitely dangerous. It places the entire realm of unsanctioned public action under a permanent cloud of suspicion, where the state’s own anxiety becomes sufficient legal grounds for clampdown. As the old adage goes, “A guard who starts shooting at shadows will soon fill the night with real corpses.” The Museveni regime, by shooting down digital “shadows,” creates a tangible corpse: the corpse of public trust and open discourse.

This transforms civic initiative into a pre-crime. A farmer pooling resources with neighbours to independently monitor crop prices could be considered “preventing” market instability. A community mapping unreliable water sources could be framed as “preventing” social unrest. The principle is infinitely elastic and thus infinitely dangerous. It places the entire realm of unsanctioned public action under a permanent cloud of suspicion, where the state’s own anxiety becomes sufficient legal grounds for clampdown. As the old adage goes, “A guard who starts shooting at shadows will soon fill the night with real corpses.” The Museveni regime, by shooting down digital “shadows,” creates a tangible corpse: the corpse of public trust and open discourse.Administrative Facades and the Evasion of Accountability

By labelling its action “purely administrative,” the UCC attempts to strip it of political meaning and, consequently, of political accountability. An administrative act is about process, not power; about rules, not rights. It suggests the decision was made by impartial technocrats simply “following the statute,” rather than by political actors serving the interests of a dictatorial system. This is a deliberate evasion. It seeks to move the debate from the high ground of democratic principle—the right to information, freedom of expression—to the low marsh of legalistic procedure, where the state’s lawyers always hold the map.

This facade crumbles under the slightest scrutiny. In a political context where the independence of public institutions has been systematically eroded over decades, no action of this magnitude is “purely” administrative. The directive to block the website followed a “formal request from the Electoral Commission,” a body whose leadership is appointed by and serves at the pleasure of the executive. The “preventive” action is; therefore, a political strategy executed through administrative machinery. It uses the letter of the law to strangle the spirit of democracy.

This facade crumbles under the slightest scrutiny. In a political context where the independence of public institutions has been systematically eroded over decades, no action of this magnitude is “purely” administrative. The directive to block the website followed a “formal request from the Electoral Commission,” a body whose leadership is appointed by and serves at the pleasure of the executive. The “preventive” action is; therefore, a political strategy executed through administrative machinery. It uses the letter of the law to strangle the spirit of democracy.The Chilling Effect: Building a Prison of the Mind

The true power of pre-emptive repression lies not only in the act itself, but in the chilling effect it radiates outward. When the state demonstrates its willingness to dismantle a platform before it can be proven to have caused any tangible harm, it sends a paralysing message to everyone else. The software developer considering a civic tech project, the journalist contemplating a data-driven investigation, the community leader thinking of organising a digital register for local grievances—all are forced to hesitate. They must now self-censor, judging their own ideas not on merit or public need, but on how a paranoid state apparatus might interpret their potential. This builds a prison of the mind, where the bars are made of “what if” and the warden is the state’s limitless suspicion.

Conclusion: The Signature of a Regime in Fear

Ultimately, a state that governs through “preventive” suppression is a state that confesses its own profound insecurity. It lacks faith in the compelling power of its own narrative and in the loyalty of its people. It admits that its continued rule relies not on winning open debates, but on preventing them from ever starting. The Museveni dictatorship, by employing this logic, reveals itself to be fundamentally anti-society. It views the spontaneous, self-organising capacity of its citizens—their ability to create, share, and verify knowledge independently—as the ultimate threat.

The “preventive” block is not a shield for the public, but a barricade erected by power to protect itself from the very people it claims to serve. It is the definitive signature of a regime that fears its own population more than anything else, and in doing so, forfeits any legitimate claim to their governance.

The “preventive” block is not a shield for the public, but a barricade erected by power to protect itself from the very people it claims to serve. It is the definitive signature of a regime that fears its own population more than anything else, and in doing so, forfeits any legitimate claim to their governance.The Shutdown as Collective Punishment: Digital Confinement of a Nation

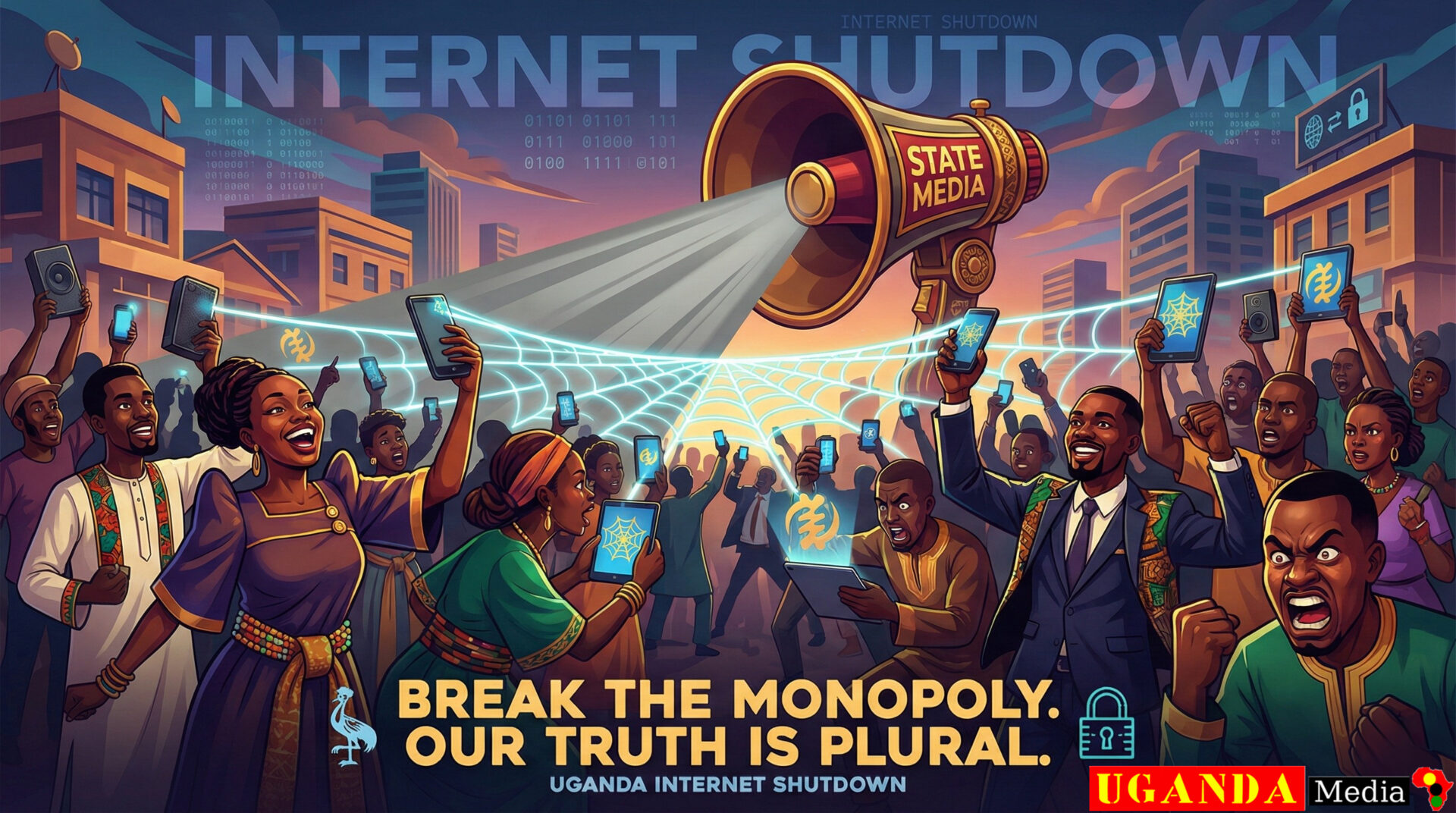

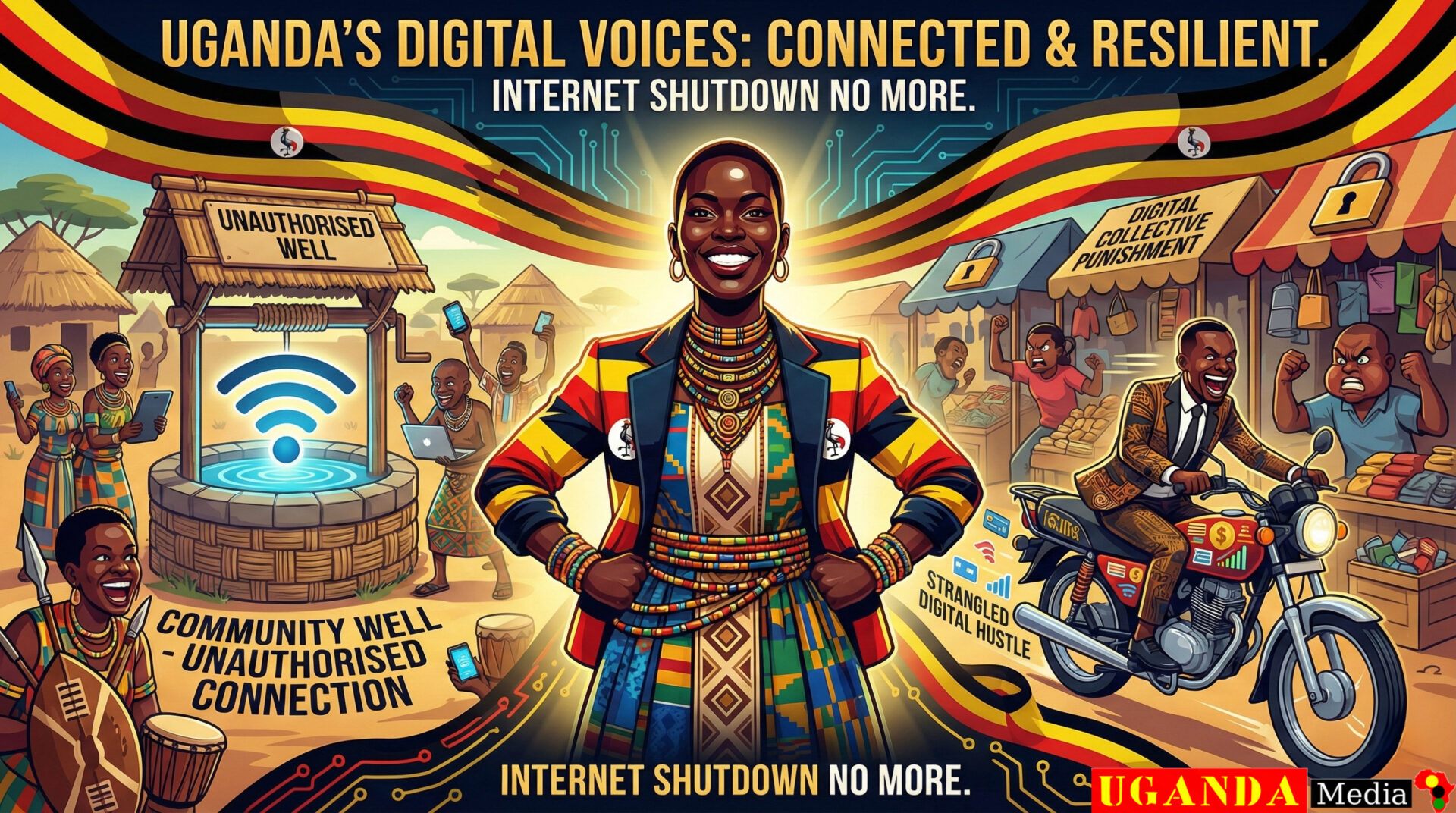

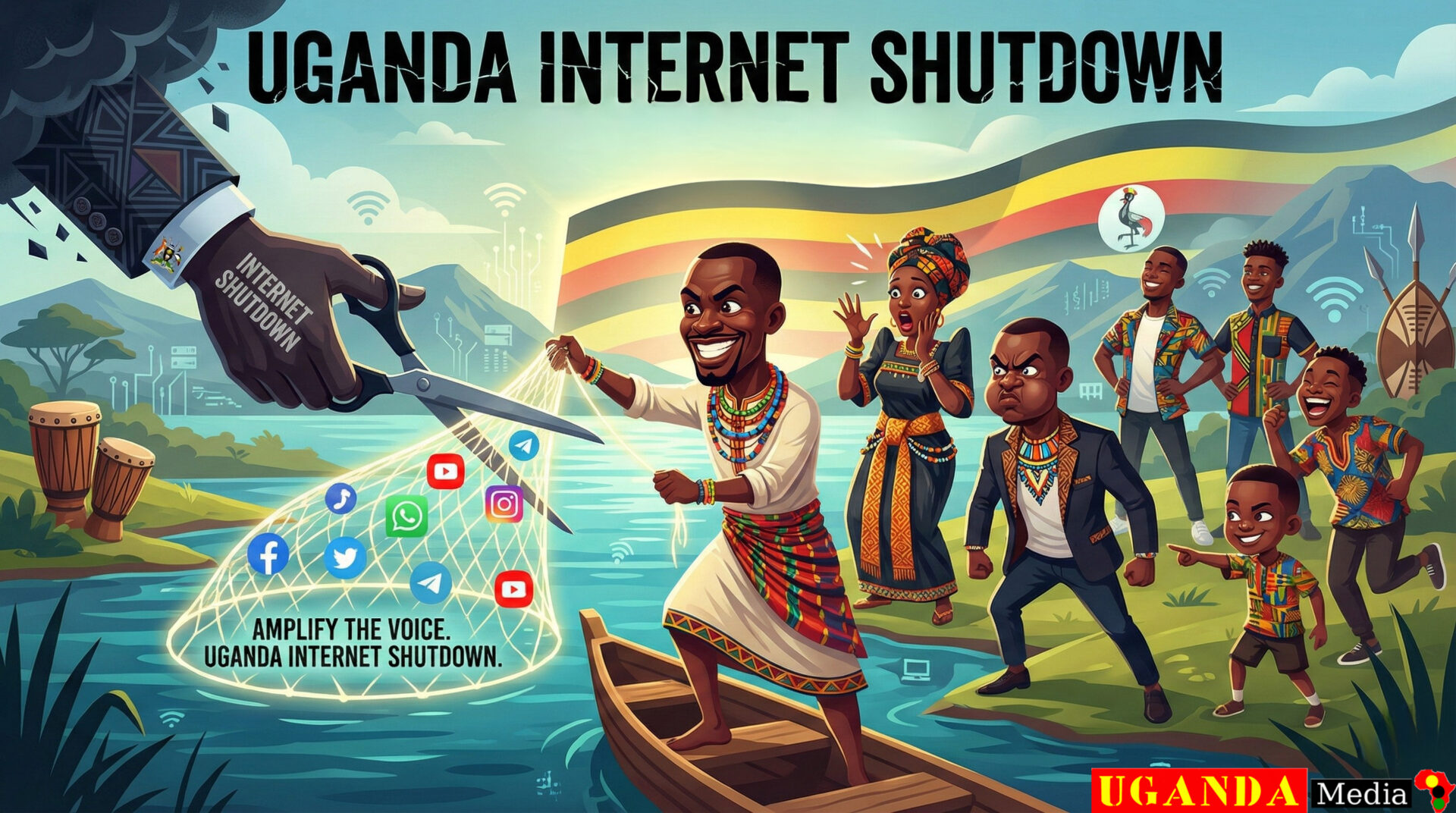

When the Uganda Communications Commission issued its second directive, ordering a blanket suspension of public internet access, it enacted a profound injustice that transcends mere technical regulation. This is not a surgical strike against alleged “misinformation”; it is the digital equivalent of imposing a nationwide curfew. It confines an entire population to a state of informational darkness, not for a crime they have committed, but for the state’s own profound fear of what free and open communication might reveal. It is, in its essence, a policy of collective punishment, where millions of ordinary Ugandans—from market vendors in Kikuubo to software developers in Nakawa, from journalists in Kampala to students in Gulu—are penalised for the anxieties of a ruling elite.

The Anatomy of a Digital Curfew

A curfew operates on a simple, brutal logic: the movements and liberties of all are restricted to pre-empt the potential actions of a few. It treats the entire community as suspect, as a threat to be managed through confinement. The internet shutdown follows this exact punitive blueprint. By severing access to social media, messaging applications, and general web browsing, the state effectively corrals public discourse. It halts the vibrant, chaotic, and essential digital life of a nation. The justification—to prevent incitement, fraud, or misinformation—is a pretext that crumbles under the weight of its own disproportionality. To silence an entire country’s voice to prevent potential “incitement” is to admit that the state views its own citizenry not as partners in a democratic process, but as a volatile mob that must be pre-emptively subdued.

This punishment is felt in the most visceral, economic terms. Consider the small business owner whose entire trade now flows through mobile money and social media advertising, suddenly cut off from customers and capital. Reflect on the freelance writer whose livelihood depends on remote communication, now rendered incommunicado and unable to work. Think of the farmer in Masaka trying to check crop prices, or the family seeking news of a loved one. Their digital lives—and the real-world sustenance and connection they derive from them—are deemed acceptable collateral damage. As the old adage poignantly observes, “When you burn down the forest to catch a single thief, you leave everyone homeless and in the dark.” The regime, in its zeal to control a narrative, sets fire to the entire digital commons upon which modern Ugandan society increasingly depends.

This punishment is felt in the most visceral, economic terms. Consider the small business owner whose entire trade now flows through mobile money and social media advertising, suddenly cut off from customers and capital. Reflect on the freelance writer whose livelihood depends on remote communication, now rendered incommunicado and unable to work. Think of the farmer in Masaka trying to check crop prices, or the family seeking news of a loved one. Their digital lives—and the real-world sustenance and connection they derive from them—are deemed acceptable collateral damage. As the old adage poignantly observes, “When you burn down the forest to catch a single thief, you leave everyone homeless and in the dark.” The regime, in its zeal to control a narrative, sets fire to the entire digital commons upon which modern Ugandan society increasingly depends.The Political Strategy of Paralysis

Beyond the economic shock, the shutdown serves a core political strategy: it is an engineered paralysis. It seeks to dismantle the very architecture of modern, horizontal organisation. In the absence of a free digital sphere, the ability to coordinate, to share evidence of irregularities, to mount a collective response, is catastrophically diminished. It forces society back into isolated, manageable units—individuals and households—severed from the networks of solidarity and mutual aid that could challenge the official story. It is a deliberate regression, a forced return to a slower, more controllable information age.

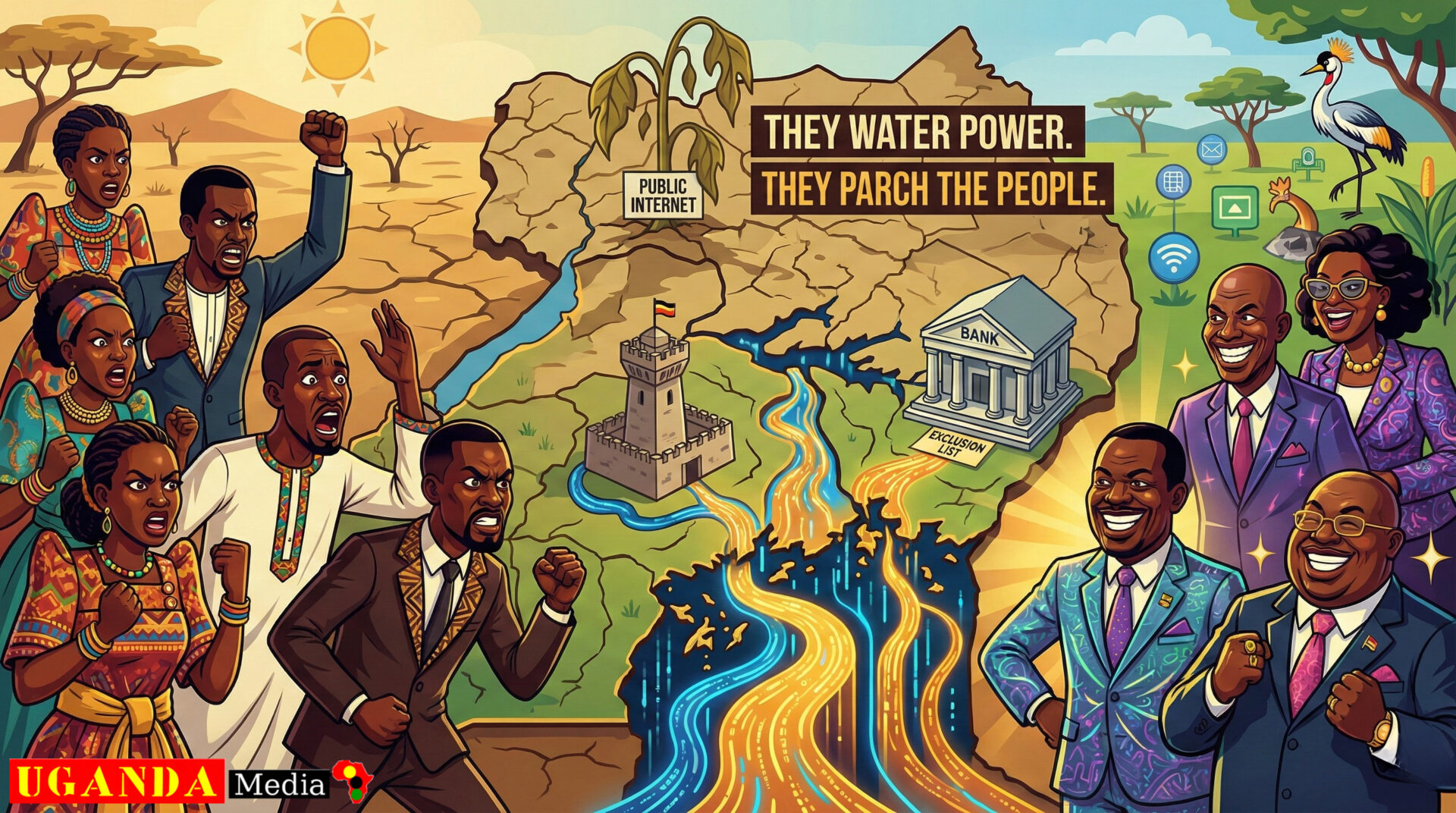

This act of collective punishment starkly illuminates the regime’s priorities. The detailed “Exclusion List” that maintains internet for banking, government payments, and security services reveals that the suspension is not about a total technological blackout. It is a targeted social blackout. The flow of money and state authority must continue uninterrupted; it is only the flow of ideas, public conversation, and communal empathy that must be stopped. This lays bare the dictatorship’s true nature: it is a system that venerates control and capital above community and conversation.

This act of collective punishment starkly illuminates the regime’s priorities. The detailed “Exclusion List” that maintains internet for banking, government payments, and security services reveals that the suspension is not about a total technological blackout. It is a targeted social blackout. The flow of money and state authority must continue uninterrupted; it is only the flow of ideas, public conversation, and communal empathy that must be stopped. This lays bare the dictatorship’s true nature: it is a system that venerates control and capital above community and conversation.A Confession of Illegitimacy

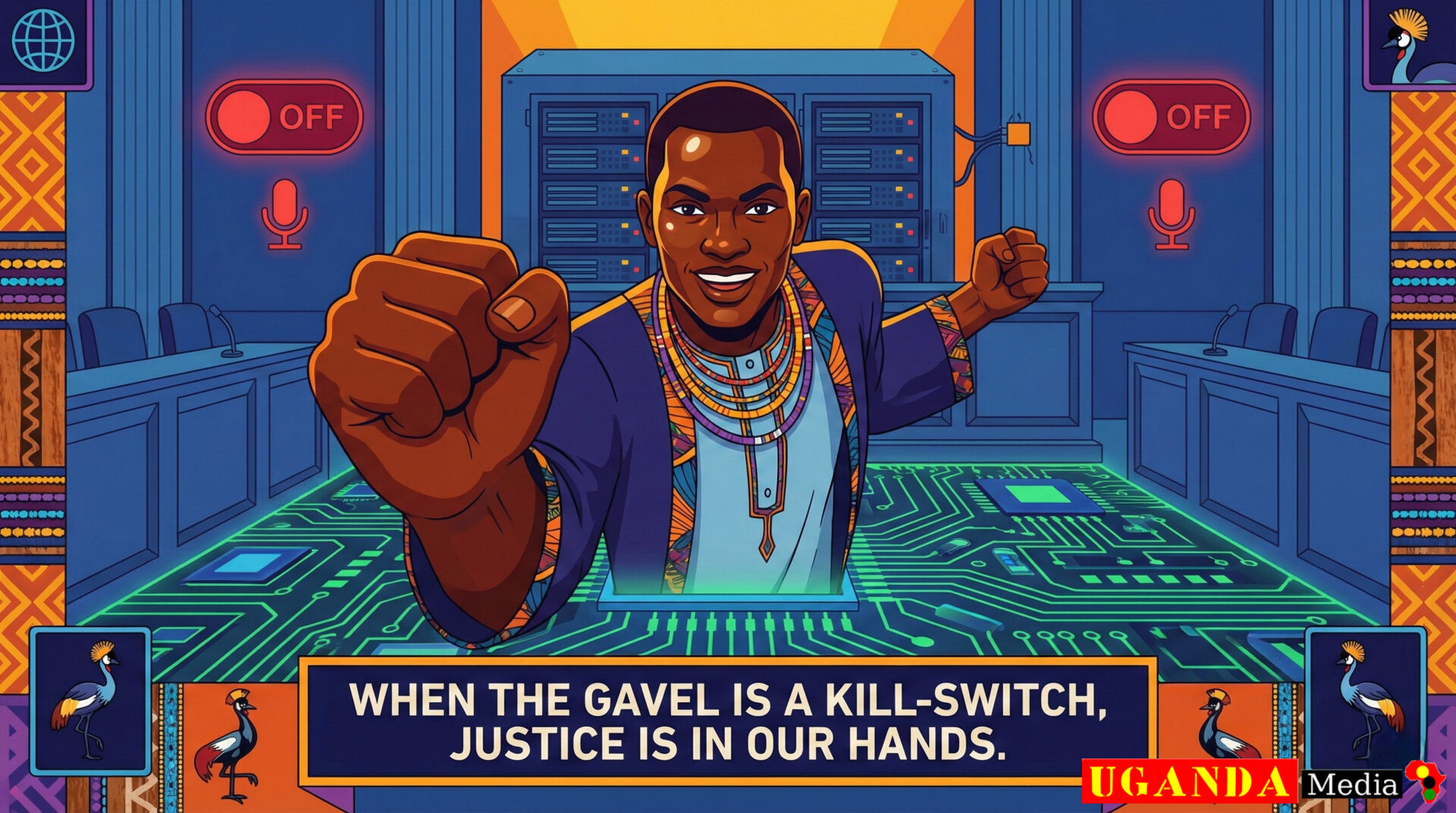

Most damningly, the resort to collective punishment through a digital curfew is a spectacular confession of political failure and profound illegitimacy. A government confident in its record, secure in its popular support, and committed to a fair electoral contest would have no need for such a draconian, scorched-earth policy. It would engage with criticism, counter misinformation with better information, and trust in the discernment of its citizens. The Museveni dictatorship’s choice to instead impose a blanket silence is an admission that it cannot win in the arena of open discourse. It fears the collective intelligence, the shared witness, and the organising potential of its own people more than any external threat.

By punishing the whole for the potential transgressions of a few, the regime demonstrates its fundamental hostility towards the very concept of a self-governing society. It declares that the people’s right to communicate, to associate freely in the digital sphere, and to participate in the unfettered exchange of ideas is subordinate to the state’s insatiable need for control. The internet shutdown is therefore more than a temporary inconvenience; it is a stark lesson in power. It teaches that the state views the people’s freedom as a threat to be neutralised, and their collective digital life as a privilege it can revoke at will. The true “national security” being protected is not that of the Ugandan people, but the security of an ageing dictatorship from the empowered, connected, and watchful gaze of its citizens.

By punishing the whole for the potential transgressions of a few, the regime demonstrates its fundamental hostility towards the very concept of a self-governing society. It declares that the people’s right to communicate, to associate freely in the digital sphere, and to participate in the unfettered exchange of ideas is subordinate to the state’s insatiable need for control. The internet shutdown is therefore more than a temporary inconvenience; it is a stark lesson in power. It teaches that the state views the people’s freedom as a threat to be neutralised, and their collective digital life as a privilege it can revoke at will. The true “national security” being protected is not that of the Ugandan people, but the security of an ageing dictatorship from the empowered, connected, and watchful gaze of its citizens.Selective Connectivity Reveals Priorities: The Regime’s Hierarchy of Needs

The second directive’s most damning feature is not its bluntness, but its precision. Within the sweeping edict for a digital blackout lies a meticulously crafted “Exclusion List.” This list is a Rosetta Stone for deciphering the true priorities of the Museveni dictatorship. It reveals, with cold clarity, a brutal hierarchy of value. The systems permitted to remain online—core banking networks, government payment gateways, tax collection portals, and international financial circuits—are not chosen for public welfare, but for systemic continuity. They ensure that the lifeblood of capital and the mechanics of state revenue continue to flow unimpeded, while the lifeblood of democracy—the free flow of ideas, solidarity, and political discourse—is deliberately stilled. This is not an act of national security; it is an act of selective sustenance, feeding the machinery of power while starving the body politic.

The Preservation of the Economic Engine

The exclusions lay bare a fundamental truth: the regime’s stability is inextricably tied to the uninterrupted functioning of financial and administrative capital. Consider what remains accessible:

Interbank transfer systems and ATM networks: Ensuring that commercial transactions and elite financial mobility face no disruption.

URA tax payment systems and government payment gateways: Guaranteeing that revenue collection—the fuel for the state’s patronage and security apparatus—never misses a beat.

International payment gateways: Allowing for the smooth continuation of cross-border commerce and financial dealings critical to connected elites.

This selective connectivity demonstrates that the state views its economic functions as non-negotiable and apolitical. The market must be served, debts must be settled, and the treasury must be filled, even as the public square is dismantled. It creates a grotesque duality: a citizen can pay their taxes online to a government that has simultaneously made it a crime to discuss how those taxes are used. They can access bank loans but cannot access the news that might explain why the economy is faltering. The message is explicit: your role as a consumer and taxpayer is essential; your role as an informed citizen and political agent is criminal.

The Abandonment of the Social Fabric

Contrast this with what is deliberately severed: every tool of mass social connection, public conversation, and grassroots organising. Social media, messaging apps, and general web access—the digital equivalents of the village square, the community noticeboard, and the whispering network—are ruthlessly cut. This dichotomy exposes the regime’s ideological blueprint. It believes a society can, and should, be disaggregated into two parts: the economic unit and the political being. The economic unit—the worker, the consumer, the taxpayer—must be kept functional. The political being—the critic, the organiser, the community witness—must be disabled.

As the old adage starkly puts it, “A master may feed the horse in its stable, but he will always hobble it before it can run free.” The exclusions are the feed in the stable: the technical sustenance for a compliant, economically productive population. The shutdown is the hobble: the deliberate restraint on that population’s capacity for collective action and independent thought. The regime is not managing a crisis; it is enforcing a specific type of order—one where financial obedience is mandatory, and political agency is forbidden.

As the old adage starkly puts it, “A master may feed the horse in its stable, but he will always hobble it before it can run free.” The exclusions are the feed in the stable: the technical sustenance for a compliant, economically productive population. The shutdown is the hobble: the deliberate restraint on that population’s capacity for collective action and independent thought. The regime is not managing a crisis; it is enforcing a specific type of order—one where financial obedience is mandatory, and political agency is forbidden.The Illusion of “Essential Services”

The inclusion of a few select public services, like National Referral Hospital systems, serves as a thin fig leaf of legitimacy. Yet, this too is revealing. How accessible are these hospital systems to the average citizen in a blackout? Without mobile communication to arrange transport, without mobile money to pay for it, and without public information channels to know where to go, the “access” is largely theoretical for many. It is a performative gesture, designed to deflect criticism, while the real operational priority remains the financial and administrative infrastructure that underpins state power.

This selective list ultimately dismantles the state’s own narrative of a “necessary” shutdown for universal safety. It proves the action is not about safety, but about control. The continuity of systems that facilitate control and capital is paramount. The continuity of systems that facilitate community, empathy, and shared understanding is deemed dangerous. It is a perfect illustration of a state that exists not to enable society, but to manage and milk it. The dictatorship is willing to paralyse the nation’s social and intellectual life, but it dare not interrupt the ticking of the cash register or the flow of funds into its own coffers. In this calibrated silence, we hear the regime’s truest voice: it values the transaction above the conversation, the ledger above the community, and its own perpetuation above the people’s right to connect, challenge, and choose.

This selective list ultimately dismantles the state’s own narrative of a “necessary” shutdown for universal safety. It proves the action is not about safety, but about control. The continuity of systems that facilitate control and capital is paramount. The continuity of systems that facilitate community, empathy, and shared understanding is deemed dangerous. It is a perfect illustration of a state that exists not to enable society, but to manage and milk it. The dictatorship is willing to paralyse the nation’s social and intellectual life, but it dare not interrupt the ticking of the cash register or the flow of funds into its own coffers. In this calibrated silence, we hear the regime’s truest voice: it values the transaction above the conversation, the ledger above the community, and its own perpetuation above the people’s right to connect, challenge, and choose.The Hypocrisy of “Critical” Services: The Facade of Care in a Crisis

The inclusion of “Healthcare systems at National Referral Hospitals” on the Exclusion List is a masterful stroke of political theatre, designed to project an image of a state that, even in its most repressive moments, retains a core of benevolent concern. It is a thin veneer of care painted over an edifice of control. To present this as evidence of a balanced, welfare-oriented policy is to fundamentally misunderstand—or deliberately obscure—the lived reality of crisis for millions of Ugandans. The stark, unanswered question hangs in the digital silence: of what use is a digital hospital portal to a citizen who cannot call for an ambulance, who cannot access mobile money to pay for transport, who cannot receive public health alerts, and whose community cannot organise to get them help? This selective connectivity does not serve the welfare of the people; it serves the infrastructure of state power, while offering the hollow spectacle of care.

The Theatre of Concern vs. The Mechanics of Survival

The dictatorship’s list betrays a cold, technocratic understanding of “critical.” To the regime, a “critical” system is one that maintains the operational facade of the state and its key economic functions. The hospital system is listed not primarily as a conduit for public aid, but as a piece of essential state infrastructure—like a power grid or a central bank—that must remain nominally functional. Its inclusion is about maintaining a capability, not about enabling access. It is the difference between keeping the lights on in a government building and ensuring every home has a candle.

For the average Ugandan facing a medical emergency during the blackout, the reality is one of profound isolation. The very tools that have woven the modern social safety net—mobile money to pay a boda boda, a WhatsApp group to alert neighbours, a phone call to a relative at the hospital for advice—are deliberately severed. The state offers a digital back door to a referral hospital’s server while bricking up every communal path leading to its actual door. This creates a cruel paradox: the system is “up,” but the people are left down, disconnected, and unable to reach it. As the piercing adage reminds us, “A lifeboat locked in a captain’s cabin saves no one from a sinking ship.” The regime, from its isolated bridge, secures its own lifeboats of critical data while leaving the passengers to drown in a sea of enforced silence and immobility.

For the average Ugandan facing a medical emergency during the blackout, the reality is one of profound isolation. The very tools that have woven the modern social safety net—mobile money to pay a boda boda, a WhatsApp group to alert neighbours, a phone call to a relative at the hospital for advice—are deliberately severed. The state offers a digital back door to a referral hospital’s server while bricking up every communal path leading to its actual door. This creates a cruel paradox: the system is “up,” but the people are left down, disconnected, and unable to reach it. As the piercing adage reminds us, “A lifeboat locked in a captain’s cabin saves no one from a sinking ship.” The regime, from its isolated bridge, secures its own lifeboats of critical data while leaving the passengers to drown in a sea of enforced silence and immobility.Power’s Infrastructure Versus People’s Networks

This exposes the central hypocrisy. The exclusions protect vertical systems of command, control, and capital—systems that flow from the populace to the state (taxes, compliance) or between elite institutions (interbank transfers). They actively dismantle horizontal systems of mutual aid and community support—the very networks people rely on in a crisis. A village savings group cannot coordinate, a community health volunteer cannot receive updates, a network of drivers cannot be mobilised. The state preserves the pinnacle of its own health infrastructure, while deliberately dissolving the grassroots web that gives that infrastructure meaning and reach.

Thus, the list is not a plan for public welfare; it is a blueprint for institutional survival. It ensures that the formal, state-recognised apparatus can be seen to be functioning, which is politically necessary for both domestic legitimacy and international optics. The chaotic, human, messy reality of whether people can actually use this apparatus is rendered irrelevant—indeed, the communication blackout ensures that evidence of any failure to access care is itself suppressed. Suffering is rendered invisible, and the state’s ledger of “critical services” remains untarnished.

Thus, the list is not a plan for public welfare; it is a blueprint for institutional survival. It ensures that the formal, state-recognised apparatus can be seen to be functioning, which is politically necessary for both domestic legitimacy and international optics. The chaotic, human, messy reality of whether people can actually use this apparatus is rendered irrelevant—indeed, the communication blackout ensures that evidence of any failure to access care is itself suppressed. Suffering is rendered invisible, and the state’s ledger of “critical services” remains untarnished.The Revelation of True Priority

This calculated move reveals the regime’s ultimate priority: the preservation of systems that authenticate and sustain its power is non-negotiable. The performance of governance must continue. The actual welfare of individuals, however, is contingent, secondary, and sacrificable to the greater goal of maintaining control. The hospital on the list is a symbol, a checkbox on a regulator’s compliance sheet. The people’s ability to reach it is dismissed as a mere logistical detail, a casualty of the “greater good” of political stability as defined solely by the dictatorship.

In the end, the hypocrisy of the “critical” services list teaches a brutal lesson. It demonstrates that in the eyes of such a state, the people are not the purpose of the infrastructure; they are its subjects, and at times, its impediment. The regime will safeguard the empty shell of a system to maintain its own claim to authority, even as it actively dismantles the living, breathing, communicating community that gives life to that system and upon which true resilience depends. It offers a digital lifeline to a select few within the fortress of state function, while pulling up every ladder of communal connection for the many outside its walls.

In the end, the hypocrisy of the “critical” services list teaches a brutal lesson. It demonstrates that in the eyes of such a state, the people are not the purpose of the infrastructure; they are its subjects, and at times, its impediment. The regime will safeguard the empty shell of a system to maintain its own claim to authority, even as it actively dismantles the living, breathing, communicating community that gives life to that system and upon which true resilience depends. It offers a digital lifeline to a select few within the fortress of state function, while pulling up every ladder of communal connection for the many outside its walls.The Silencing of Grassroots Mobilisation: Severing the Sinews of Self-Organisation

The UCC directive’s surgical precision in targeting social media, messaging applications, and general web access is not a hapless swing at “misinformation.” It is a deliberate and calculated strike at the very architecture of modern grassroots mobilisation. This move seeks to cripple the tools that facilitate horizontal organisation—the spontaneous, person-to-person, community-driven coordination that operates outside the formal, hierarchical channels of the state and its sanctioned institutions. By severing these digital sinews, the regime of Yoweri Museveni aims to render impossible the very forms of mutual aid, independent oversight, and collective action that represent the most potent, organic challenge to its top-down control.

The Anatomy of Horizontal Power

True popular power has never flowed solely from formal institutions or periodic elections. It resides in the daily, often invisible, web of communal connections and cooperative action. Consider the practical fabric of Ugandan society: a network of market vendors warning each other of supply issues via WhatsApp; a community savings group in Jinja coordinating contributions for a member’s emergency; residents in a Kampala suburb using a Facebook group to document inconsistent water supply and collectively pressure authorities; or farmers in Teso sharing weather data and crop prices through simple messaging apps. These are not political acts in the partisan sense, but they are profoundly political in essence—they represent people managing their own affairs, building resilience from the ground up, and creating shared knowledge independent of official diktat.

The state’s blackout is a direct assault on this organic capacity. It recognises that the greatest threat to a rigid, centralised authority is not a single opposing party, but a population that can think, communicate, and act collectively without seeking its permission. Tools like encrypted messengers or social media platforms are the modern equivalents of the village drum or the community noticeboard—instruments for rapid, decentralised communication that enable people to respond to events in real time, based on shared local knowledge rather than filtered official statements.

The state’s blackout is a direct assault on this organic capacity. It recognises that the greatest threat to a rigid, centralised authority is not a single opposing party, but a population that can think, communicate, and act collectively without seeking its permission. Tools like encrypted messengers or social media platforms are the modern equivalents of the village drum or the community noticeboard—instruments for rapid, decentralised communication that enable people to respond to events in real time, based on shared local knowledge rather than filtered official statements.Neutralising the Watchdogs and Weakening the Weave

During an election period, this capacity for horizontal organisation is doubly dangerous to an insecure regime. It enables:

Independent Election Monitoring: Where citizens, not just foreign or partisan observers, can document queues, incidents, or irregularities at polling stations and instantly collate this data into a public, verifiable record that bypasses the Electoral Commission’s monopoly on truth.

Community Alerts and Protection: Where neighbourhoods can quickly share information about security deployments, movements, or disturbances, creating a form of collective situational awareness that counters the state’s exclusive narrative of “order.”

Mutual Aid Logistics: Where volunteers can coordinate the distribution of water, electricity backups, or transport during periods of deliberately engineered uncertainty or restriction.

By silencing these tools, the state does not just ban “politics”; it bans societal resilience and communal self-defence. It forces people back into atomised isolation, where they can only receive information vertically—from the state downwards—and can only respond as individuals, not as a community. As the adage goes, “A chain is only as strong as its links, but a web cannot be broken by cutting a single thread.” The regime understands this. It does not fear individual dissidents; it fears the web. Its strategy, therefore, is not to cut a single thread but to dissolve the entire connective tissue, rendering the web inert.

The Revealing Target: Solidarity, Not Sedition

What is most telling is what the state chooses not to block in this category. It does not merely block known opposition websites. It blocks the very platforms of everyday social and economic life—the same platforms used to arrange a child’s birthday party, to sell crafts, or to check on an elderly relative. This reveals that the target is not seditious content, but solidarity itself in any form that it cannot directly monitor and mediate. The state views any unmonitored gathering of minds—whether to discuss politics, prices, or potholes—as a potential council of resistance.

This action exposes the dictatorship’s fundamental antipathy towards the concept of an active, self-organising citizenry. A confident government would see vibrant grassroots networks as partners in community resilience. A paranoid dictatorship sees them as a shadow government in waiting. The blackout is, therefore, a pre-emptive coup against civil society in its broadest, most organic sense. It is an admission that the regime’s vision for Uganda is one of a managed populace, not an empowered people; of subjects who receive instructions, not citizens who build solutions together. In silencing the tools of grassroots mobilisation, the state seeks to silence the very hum of society thinking and acting for itself, leaving only the sterile, monolithic voice of authority echoing in the void.

This action exposes the dictatorship’s fundamental antipathy towards the concept of an active, self-organising citizenry. A confident government would see vibrant grassroots networks as partners in community resilience. A paranoid dictatorship sees them as a shadow government in waiting. The blackout is, therefore, a pre-emptive coup against civil society in its broadest, most organic sense. It is an admission that the regime’s vision for Uganda is one of a managed populace, not an empowered people; of subjects who receive instructions, not citizens who build solutions together. In silencing the tools of grassroots mobilisation, the state seeks to silence the very hum of society thinking and acting for itself, leaving only the sterile, monolithic voice of authority echoing in the void.The Criminalisation of Circumvention: Outlawing the Human Impulse to Connect

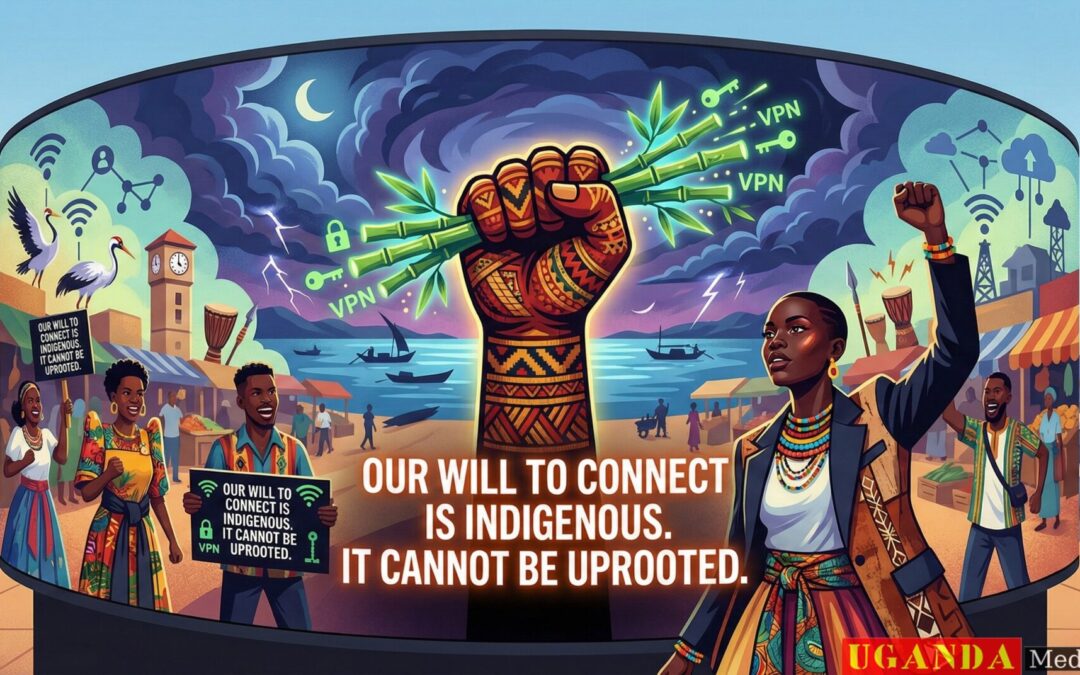

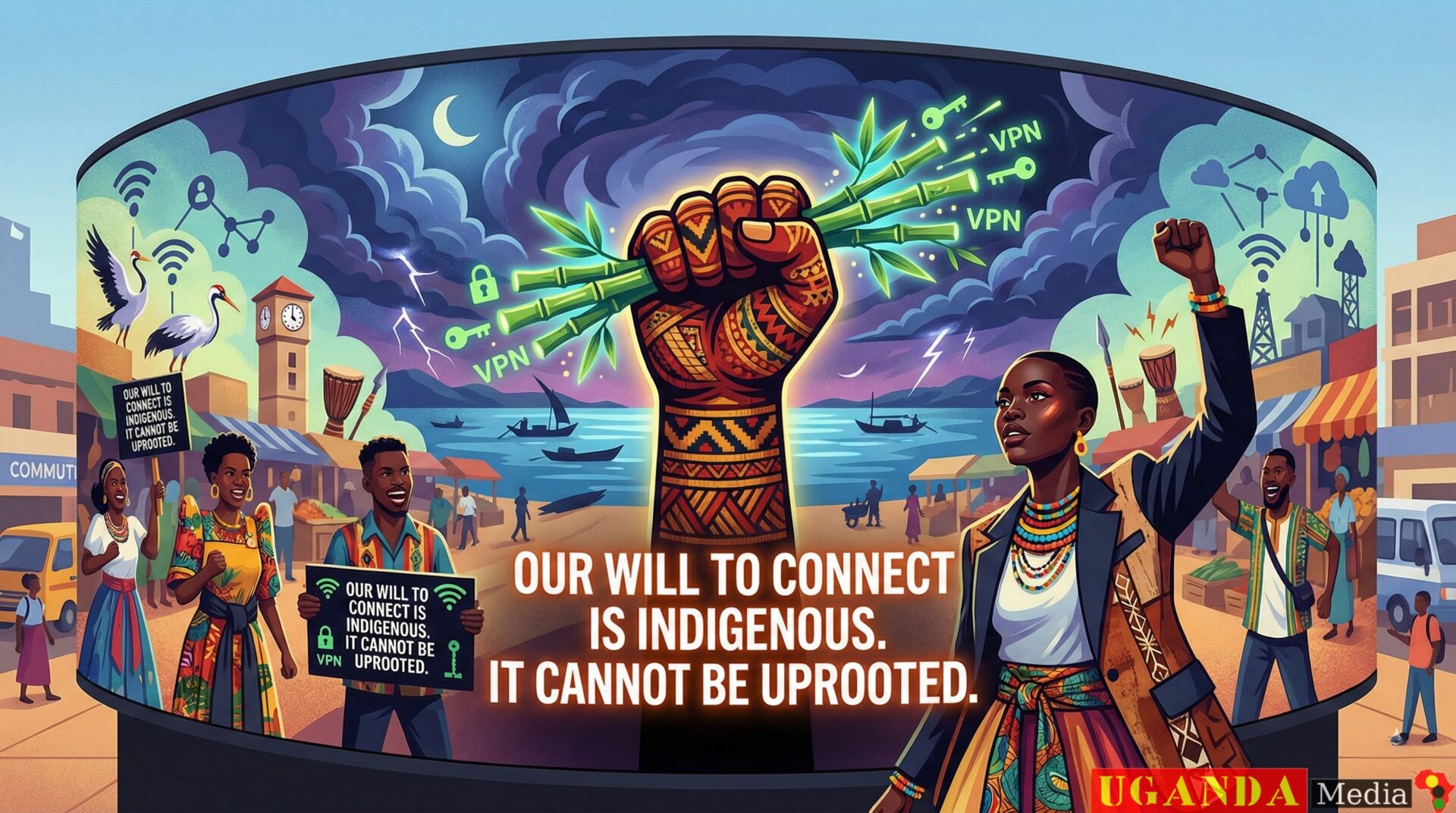

The directive’s command to disable mobile Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) and to prohibit “any form of public bypass” transcends mere technical regulation. It is a declaration of total digital siege. This edict does not simply close the gates of information; it stations guards at every potential crack in the wall with orders to shoot. It pathologises and criminalises the innate human impulse to communicate, to seek knowledge, and to connect with others beyond imposed barriers. By rendering the very act of circumvention a primary offence, the Museveni dictatorship reveals its ultimate ambition: not just to control the official narrative, but to suffocate the independent will that seeks alternatives to it.

The Digital Siege: From Restriction to Total Enclosure

A restriction acknowledges the existence of something beyond its boundary. A siege aims to create a perfect, inescapable enclosure. The initial internet suspension was a restriction—a blunt closure of main gates (social media, browsing). But the order concerning VPNs and bypasses is the siege work: the filling of moats, the welding shut of sewer grates, the denial of any secret path. A VPN, in this context, is not a tool for illicit activity; it is a digital expression of a basic human right—the right to privacy and to seek information freely. It is the technological equivalent of whispering in a crowd, of passing a note, of finding a hidden path through a forest when the main road is blocked by soldiers. To outlaw this is to outlaw ingenuity itself, to declare that the state’s artificial reality is the only permissible plane of existence.

This move exposes the regime’s understanding that control, to be absolute, must be psychological as much as technical. It seeks to instil a feeling of futility. The message is: “Do not even think of reaching beyond what we allow. Your curiosity is criminal. Your desire to connect with others outside our sanctioned channels is a threat.” It transforms every citizen with a smartphone from a potential communicator into a potential suspect, where the mere act of installing a privacy tool becomes a latent act of defiance. As the adage starkly frames it, “A jailer who fears the tapping of pipes has already admitted that his prison is built on sand.” The regime’s hysterical focus on stopping every “bypass” confesses its deep insecurity; it knows its wall of control is fragile, that the human will to connect is a relentless, eroding force.

This move exposes the regime’s understanding that control, to be absolute, must be psychological as much as technical. It seeks to instil a feeling of futility. The message is: “Do not even think of reaching beyond what we allow. Your curiosity is criminal. Your desire to connect with others outside our sanctioned channels is a threat.” It transforms every citizen with a smartphone from a potential communicator into a potential suspect, where the mere act of installing a privacy tool becomes a latent act of defiance. As the adage starkly frames it, “A jailer who fears the tapping of pipes has already admitted that his prison is built on sand.” The regime’s hysterical focus on stopping every “bypass” confesses its deep insecurity; it knows its wall of control is fragile, that the human will to connect is a relentless, eroding force.The Illusion of “Public” vs “Private” Access

The prohibition on “public bypass” is a carefully constructed deception. It implies a legitimate, private channel exists. But in a total suspension, where all standard access is cut, the distinction is meaningless. The “exclusions” are for institutional, state-aligned functions (banking, government payments), not for private, civic discourse. Therefore, any tool a private citizen uses to access the global internet becomes, by the state’s definition, a “public bypass.” This semantic trick criminalises the personal and the communal. It frames a student researching, a journalist contacting a source, or a family video-calling relatives abroad as participating in a “public” breach of security, equating personal communication with a threat to the state.

This has a deeply chilling effect on solidarity. It aims to atomise resistance before it can even form. If neighbours cannot secretly coordinate, if communities cannot share secure channels, if whispers cannot become a collective voice, then the only organisation that remains is the vertical, top-down kind commanded by the state itself. It is a pre-emptive strike against the very concept of a private, collective conscience operating outside the regime’s surveillance.

This has a deeply chilling effect on solidarity. It aims to atomise resistance before it can even form. If neighbours cannot secretly coordinate, if communities cannot share secure channels, if whispers cannot become a collective voice, then the only organisation that remains is the vertical, top-down kind commanded by the state itself. It is a pre-emptive strike against the very concept of a private, collective conscience operating outside the regime’s surveillance.The Ultimate Admission: Fear of the Unmediated Mind

By criminalising circumvention, the dictatorship admits its greatest fear: the unmediated, self-directed connection between people. It is not solely afraid of specific messages; it is afraid of the autonomy that tools like VPNs represent. A populace that can choose its own sources, that can privately verify facts, that can organise in encrypted spaces, is a populace that has mentally exited the state’s panopticon. This represents a fundamental loss of ideological control.

Therefore, this aspect of the directive is the most telling. It shows the regime moving beyond managing an election period and into the realm of social engineering. Its goal is to cultivate a citizenry that internalises the boundaries of permissible thought, that stops seeking ways over the wall because the very idea of the “outside” has been erased. It is an attempt to engineer not just compliance, but intellectual submission. However, in doing so, it commits a profound error. It mistakes a technical victory for a social one. You can block a VPN connection, but you cannot block the yearning for truth and community that created the desire to use it. That yearning, once awakened and then forcibly repressed, does not vanish. It transforms, waiting for its next, inevitable expression. The regime, in its siege, may silence the pipes, but it only amplifies the pressure building beneath its foundations.

Therefore, this aspect of the directive is the most telling. It shows the regime moving beyond managing an election period and into the realm of social engineering. Its goal is to cultivate a citizenry that internalises the boundaries of permissible thought, that stops seeking ways over the wall because the very idea of the “outside” has been erased. It is an attempt to engineer not just compliance, but intellectual submission. However, in doing so, it commits a profound error. It mistakes a technical victory for a social one. You can block a VPN connection, but you cannot block the yearning for truth and community that created the desire to use it. That yearning, once awakened and then forcibly repressed, does not vanish. It transforms, waiting for its next, inevitable expression. The regime, in its siege, may silence the pipes, but it only amplifies the pressure building beneath its foundations.The Threat of “Severe Sanctions”: Co-opting Commerce into the Machinery of Control

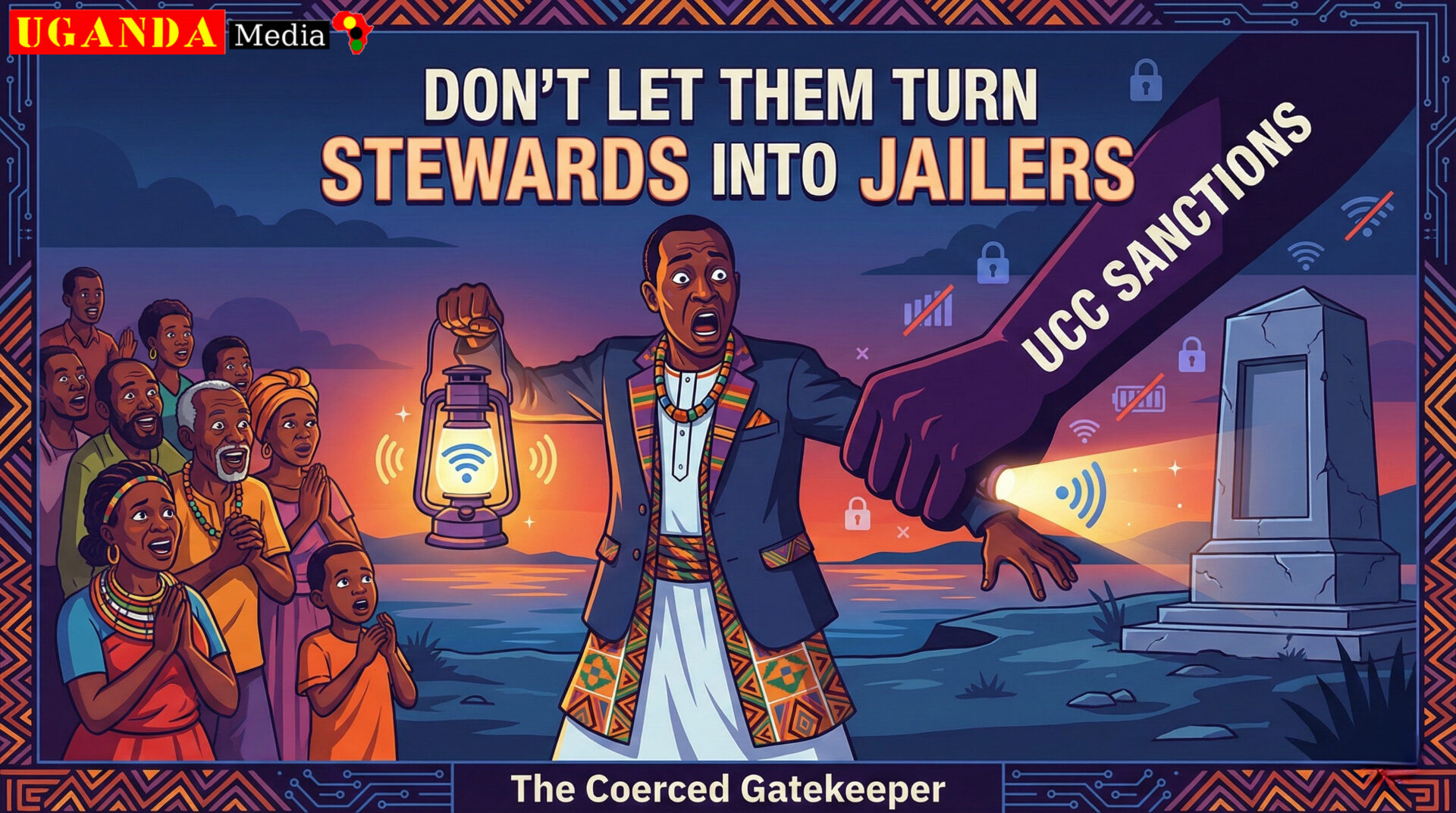

The directive’s stark warning that “Non-compliance will attract severe sanctions, including fines and potential license suspension” is not a mere clause in a regulatory document. It is the exposed mechanism of coercive force, the point where the state’s will is welded directly to the economic survival of private enterprise. This threat transforms internet service providers (ISPs) and mobile network operators from commercial entities into conscripted enforcers, blurring any meaningful line between corporate operation and governmental oppression. It demonstrates how the Museveni dictatorship leverages economic life itself as a weapon to achieve political silence, forcing the private sector to become the operational limb of its censorship apparatus.

The Economics of Compulsory Compliance

For a business, a licence is its lifeline—the legal and operational foundation of its existence, its investment, and its workforce. The threat to revoke it is existential. Similarly, a severe fine can cripple operations. By wielding these tools, the state bypasses any need to persuade or debate. It issues a blunt ultimatum: become an agent of our repression, or cease to exist. This creates a chilling form of compulsory partnership. The engineer who maintains network stability must now also be the censor who implements blacklists. The company lawyer ensuring regulatory compliance must now enforce directives that violate the spirit of free communication. The corporation’s pursuit of profit is forcibly aligned with the regime’s project of control.

This coerced alignment dismantles the notion of the private sector as any kind of independent sphere. It becomes an annex of the state security apparatus. The ISP’s technical infrastructure—its towers, fibre cables, and servers—is no longer neutral. It is weaponised. Its customer service protocols become mechanisms for enforcing a digital curfew. Its relationship with subscribers transforms from one of service provision to one of surveillance and restriction. As the old adage goes, “When the blacksmith is forced to forge only chains, every piece of iron in the land becomes a potential shackle.” The state, by threatening the smith’s very workshop, ensures that the entire telecommunications infrastructure is bent to the purpose of confinement.

This coerced alignment dismantles the notion of the private sector as any kind of independent sphere. It becomes an annex of the state security apparatus. The ISP’s technical infrastructure—its towers, fibre cables, and servers—is no longer neutral. It is weaponised. Its customer service protocols become mechanisms for enforcing a digital curfew. Its relationship with subscribers transforms from one of service provision to one of surveillance and restriction. As the old adage goes, “When the blacksmith is forced to forge only chains, every piece of iron in the land becomes a potential shackle.” The state, by threatening the smith’s very workshop, ensures that the entire telecommunications infrastructure is bent to the purpose of confinement.The Blurred Line and the Corruption of Purpose

This forced conscription creates a dangerous fusion. It is no longer simply the Uganda Communications Commission policing content; it is every ISP manager and network technician made personally responsible for executing the political will of the regime. This corrupts the very purpose of communications technology. Its foundational principle—to connect people—is forcibly inverted into a mandate to disconnect and isolate. The private company’s brand, built on promises of connectivity and access, is now legally obligated to enact its opposite: disconnection and denial.

This system also manufactures a layer of deniability for the state. The regime can claim it is merely “regulating” private actors, who are “independently” implementing the rules. In reality, it has created a scenario where the private actors have no independent will. The violence of the shutdown is thus outsourced, its technical execution wearing the face of corporate logos rather than only police badges. This diffuses direct accountability while intensifying the effect, as companies use their own expertise to make the censorship more efficient and comprehensive than state actors ever could alone.

The Cultivation of a Compliant Corporate Landscape

Beyond immediate enforcement, this threat of “severe sanctions” serves a longer-term strategic goal: shaping the corporate landscape itself. It ensures that only companies willing to act as political instruments can thrive—or even survive. It deters ethically-minded investors or entrepreneurs who might prioritise principles of net neutrality or digital rights. Over time, it cultivates a telecommunications sector populated by entities selected for their pliability, whose business model incorporates anticipated compliance with political repression as a core operational cost.

This reveals the dictatorship’s holistic view of power. It does not see the economy and the polity as separate realms. It sees the economic sphere as a garden to be cultivated to bear the fruit of political control. The threat against ISPs is a stark lesson to all sectors: your commercial viability is contingent upon your utility to the regime’s political project. Your autonomy is an illusion that can be revoked at any moment.

Ultimately, the “severe sanctions” are more than a penalty; they are a pedagogy of power. They teach that in this system, there is no sanctuary, no apolitical professional space. Every boardroom, every server farm, every customer service centre is a potential annex of the state’s security committee. The directive forces a grim choice upon commerce: become the steward of the people’s connectivity, or become the state’s jailer of their communication. By choosing the latter to survive, these companies don’t just comply with oppression—they become its essential, wired-in architecture, proving that the most effective cage is one where the keepers are also prisoners of their own economic fear.

Ultimately, the “severe sanctions” are more than a penalty; they are a pedagogy of power. They teach that in this system, there is no sanctuary, no apolitical professional space. Every boardroom, every server farm, every customer service centre is a potential annex of the state’s security committee. The directive forces a grim choice upon commerce: become the steward of the people’s connectivity, or become the state’s jailer of their communication. By choosing the latter to survive, these companies don’t just comply with oppression—they become its essential, wired-in architecture, proving that the most effective cage is one where the keepers are also prisoners of their own economic fear.A System Built on Distrust: The Architecture of Permanent Suspicion

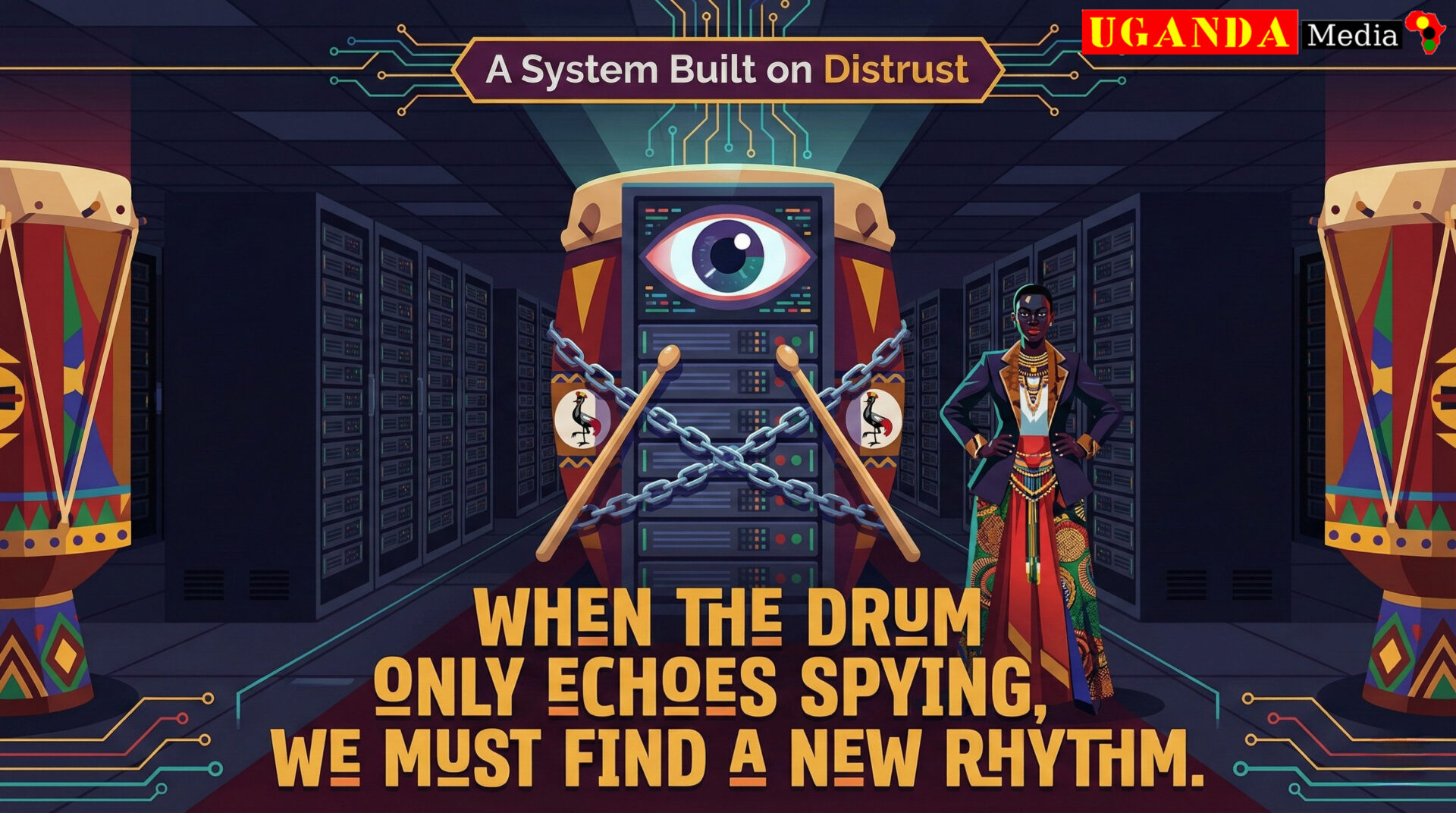

The directive’s stipulation for round-the-clock monitoring, exhaustive traffic logs, and immediate incident reporting to the Uganda Communications Commission is not a protocol for technical management. It is the blueprint for a system founded upon a profound and pervasive distrust. This framework reveals a regime that views every licensed operator not as a partner in public service, but as a potential insurgent in its network, and by logical extension, sees every citizen using that network as a latent insubordinate whose digital life must be pre-emptively policed. It is the institutionalisation of paranoia as policy, constructing an architecture where compliance is synonymous with survival, and autonomy is treated as a system fault.

The Panopticon as Policy

The mandate for constant vigilance transforms Network Operations Centres (NOCs) from hubs of maintenance into cells of surveillance. The requirement to maintain “detailed logs of all traffic on excluded systems” and to make them available for UCC inspection upon request, establishes a principle of total retrospective accountability. No action within the system is ephemeral; every data packet in the whitelisted zones of the crippled network is recorded, awaiting future audit. This creates a digital panopticon for the service providers themselves: they can never know when the regulator might scrutinise their logs, so they must act as if every moment is being watched. This internalises the state’s distrust, forcing companies to surveil themselves with the rigour the state would apply.

This logic, however, cannot be contained. A system that views its own licensed, vetted, and corporate partners with such suspicion has already rendered a verdict on the wider populace. If the CEOs and engineers of telecom firms are considered potential bypass enablers requiring this level of oversight, then the teacher, the market vendor, or the student using a mobile phone is implicitly judged as a far greater security concern. The operator’s log becomes a proxy for the citizen’s potential thought-crime. As the adage grimly observes, “A master who counts his spoons every night will never trust a guest at his table.” The regime, by counting every digital ‘spoon’ in the network’s drawer, confesses it sees only thieves in its midst, never guests or partners in a shared society.

This logic, however, cannot be contained. A system that views its own licensed, vetted, and corporate partners with such suspicion has already rendered a verdict on the wider populace. If the CEOs and engineers of telecom firms are considered potential bypass enablers requiring this level of oversight, then the teacher, the market vendor, or the student using a mobile phone is implicitly judged as a far greater security concern. The operator’s log becomes a proxy for the citizen’s potential thought-crime. As the adage grimly observes, “A master who counts his spoons every night will never trust a guest at his table.” The regime, by counting every digital ‘spoon’ in the network’s drawer, confesses it sees only thieves in its midst, never guests or partners in a shared society.The Cultivation of a Compliance Mentality

The demand for “immediate reporting” within 30 minutes of any “suspected breach or compliance challenge” is a mechanism to enforce a culture of anxious obedience. It places the onus on the operator to interpret and police the state’s vague directives in real-time, under threat of sanction. This has a corrosive effect on professional judgement. It incentivises over-reporting, pre-emptive blockage, and extreme risk-aversion. A technical anomaly, a surge in encrypted traffic from a hospital server, or even an internal testing procedure could be flagged as a “suspected breach” by a terrified engineer keen to demonstrate vigilance. This transforms the network operator from a service provider into a nervous informant, its technical staff into an extension of the security apparatus.

This system is explicitly designed to eliminate discretion, solidarity, or ethical resistance from within the corporate structure. It ensures there is no room for a technician to quietly look the other way, or for a manager to question the proportionality of a directive. The protocol of instant reporting severs any potential for a quiet, collective pause or a professional consensus that might resist an overreach. It atomises the operators just as the shutdown atomises the public, breaking down any potential for a unified, principled stand from within the industry.

This system is explicitly designed to eliminate discretion, solidarity, or ethical resistance from within the corporate structure. It ensures there is no room for a technician to quietly look the other way, or for a manager to question the proportionality of a directive. The protocol of instant reporting severs any potential for a quiet, collective pause or a professional consensus that might resist an overreach. It atomises the operators just as the shutdown atomises the public, breaking down any potential for a unified, principled stand from within the industry.The Revelation of Insecurity and the Absence of Social Contract

Ultimately, this obsession with logs, monitoring, and instant compliance is the signature of a power structure that knows its authority is illegitimate and brittle. Trust is the glue of any functional social contract; it is the belief that institutions and citizens will generally act in good faith. The Museveni dictatorship, by constructing this labyrinth of verification and threat, formally renounces that contract. It declares that good faith does not exist—only the constant potential for betrayal, which must be managed by relentless scrutiny.

This reveals a profound truth: a regime that invests so heavily in systems of distrust is one that has failed to command genuine trust. It cannot rely on loyalty, shared purpose, or voluntary cooperation, so it must instead rely on enforceable fear. The detailed logs are not just data; they are the autopsy reports of a dead social compact, evidence of a relationship reduced to that of jailer and inmate, where every action is recorded in the ledger of control. In building this system, the dictatorship does not secure a nation; it merely documents, in exhaustive detail, its own isolation and the depth of its fear of the very people it claims to lead.

The Myth of “Temporary” Measures: The Ratchet of Permanent Control

The assurance that the internet suspension and related measures are “temporary,” to be lifted only upon an “explicit written notice from the UCC,” is a carefully embedded myth designed to pacify immediate outrage. It is a plea for public patience based on a profound historical falsehood. Across the globe, and indeed within Uganda’s own recent history, so-called “temporary” emergency powers have a notorious habit of calcifying into permanent features of the political architecture. Each election cycle, each moment of perceived crisis, becomes an opportunity not to protect a fleeting public order, but to test, expand, and normalise new mechanisms of control. What is introduced as an emergency brake is rarely fully released; instead, it becomes a new baseline, a tightened ratchet on public freedom that only ever turns one way.

The Erosion by Increment

This process relies on the psychology of incrementalism. A complete and permanent announcement of such sweeping digital controls would likely meet fiercer resistance, both domestically and internationally. By framing it as a finite, event-specific measure, the regime lowers the initial cost of imposition. The public, businesses, and diplomats are encouraged to see it as an unfortunate but contained surgical procedure. However, once the technical infrastructure for a total shutdown has been built, tested, and compliance enforced across all operators, it ceases to be an extraordinary measure. It becomes a proven capability, a button on the desk of power. Its very existence creates a temptation for future use.

The normalisation occurs through repetition. If a blackout is enacted in 2021, again in 2026, the precedent is set. It transitions from a shocking aberration to an anticipated part of the “election season” ritual. Each repetition wears down public resistance, conditions businesses to build contingency plans for state-mandated silence, and teaches a new generation that this is simply how things are done. The “temporary” becomes cyclical, and the cyclical becomes a permanent fixture of political life. As the adage warns, “Beware the door built for a storm; once the frame is set, it will be used to lock out the breeze on a sunny day.” The emergency framework, once its sturdy frame is installed, is inevitably repurposed for everyday control.

The normalisation occurs through repetition. If a blackout is enacted in 2021, again in 2026, the precedent is set. It transitions from a shocking aberration to an anticipated part of the “election season” ritual. Each repetition wears down public resistance, conditions businesses to build contingency plans for state-mandated silence, and teaches a new generation that this is simply how things are done. The “temporary” becomes cyclical, and the cyclical becomes a permanent fixture of political life. As the adage warns, “Beware the door built for a storm; once the frame is set, it will be used to lock out the breeze on a sunny day.” The emergency framework, once its sturdy frame is installed, is inevitably repurposed for everyday control.The Expanding Definition of “Emergency”