A Sovereign Dilemma: Monarch, Dictator, and the Search for Uganda’s Democratic Soul

In a pointed Christmas address, Kabaka Ronald Muwenda Mutebi II, the King of Buganda, appealed for an end to electoral violence and impartiality from Uganda’s Electoral Commission. This intervention, however, transcends a simple plea for peace. It strikes at the heart of a profound national contradiction: a hereditary monarch intervening in the affairs of a sovereign republic, highlighting the fragile and often fractured nature of power in contemporary Uganda. This analysis moves beyond the immediate headlines of campaign clashes to interrogate the deeper structures at play. We examine the historical role of traditional authority, the entrenched nature of the Museveni dictatorship, and the systemic issues—from the contentious Mailo land system to a captured electoral process—that perpetuate inequality and violence. Ultimately, we argue that the true path forward lies not in appeals to existing elites, but in the cultivation of genuine, grassroots power built on community solidarity, direct democracy, and a reclamation of popular sovereignty from all forms of unaccountable authority.

Thrones and Thorns: A Monarch’s Christmas Carol in a Republic’s Storm

Introduction

As the dust of campaign trails mingles with the haze of the dry season, a royal voice rings out from the gates of the Bulange in Mengo. Kabaka Ronald Muwenda Mutebi II, the King of Buganda, has issued a Christmas message calling for electoral peace and impartiality. To the casual observer, it is a noble plea for civility. But from the hills of Kigezi to the streets of Gulu, a more critical question echoes: in a sovereign republic, what is the role of a hereditary monarch in the political fray? This intervention is not merely a sermon for peace; it is a revealing moment that lays bare the intricate theatre of power in Uganda, where colonial-era relics and modern authoritarianism dance a delicate, often parasitic, waltz against the enduring struggle of the people.

Deconstructing Power: Twenty Critical Perspectives on Monarchy, Republic, and Popular Struggle in Uganda

The Gilded Cage of Neutrality: A Monarch’s Voice in a Dictator’s Shadow

In the political theatre of modern Uganda, where the relentless engine of the Museveni dictatorship grinds against the daily realities of its people, certain figures occasionally step onto the stage to deliver soliloquies of conscience. The recent intervention by the Kabaka of Buganda, calling for electoral peace and impartiality, is one such performance. At first glance, it is a noble appeal for order and fairness. Yet, when examined under the stark sunlight of our reality, this positioning reveals itself not as a solution, but as a profound illusion—one that ultimately helps to preserve the very structures of oppression it claims to critique. It brings to mind the old adage: a wolf in sheep’s clothing is still a wolf.

The Kabaka, by virtue of his hereditary throne, assumes the mantle of a neutral arbiter—a paternal figure standing above the messy fray of politics. He becomes a moral compass in a storm of conflict. But this neutrality is a carefully constructed myth. No authority born of lineage and sustained by vast, unearned land holdings and cultural privilege can be neutral in a society defined by profound inequality and state violence. His platform itself is a product of a hierarchical system, one that mirrors the very top-down power dynamics used by the state to control and subdue.

The danger of this illusion is twofold. First, it implicitly legitimises the idea that our political crisis is merely a technical malfunction—a matter of unruly security forces or a biased Electoral Commission that simply needs ethical recalibration. This framing lets the core of the dictatorship off the hook. It suggests the system would work perfectly if only its agents behaved with civility, ignoring that the system itself—a monolithic, personalist regime maintained by coercion and patronage—is fundamentally designed to exclude, to dominate, and to perpetuate itself. The dictator’s power is not an accident; it is the architecture.

The danger of this illusion is twofold. First, it implicitly legitimises the idea that our political crisis is merely a technical malfunction—a matter of unruly security forces or a biased Electoral Commission that simply needs ethical recalibration. This framing lets the core of the dictatorship off the hook. It suggests the system would work perfectly if only its agents behaved with civility, ignoring that the system itself—a monolithic, personalist regime maintained by coercion and patronage—is fundamentally designed to exclude, to dominate, and to perpetuate itself. The dictator’s power is not an accident; it is the architecture.Second, and more insidiously, this call for peace from a traditional authority acts as a pressure valve. When frustration and anger boil over due to blocked rallies, disappeared activists, or the farcical nature of managed elections, the voice of a revered monarch channelling that anger into a plea for “calm” and “respect for the law” serves a specific function. It redirects legitimate rage away from the roots of the problem and into the safe, dead-end corridors of appealing to the better nature of the oppressors. It teaches people to seek salvation from a higher authority, rather than to recognise and build their own collective power. It is the politics of the petition, not of the protest; of the subject, not of the citizen.

We see this dynamic play out in the endless cycles of Ugandan politics. The market vendor harassed by KCCA officials and police, the farming community evicted for a connected investor’s project, the university student arrested for a social media post—their struggles are fragmented. They are told to seek justice through courts beholden to the regime, or to wait for a benevolent intervention from figures of stature. The Kabaka’s statement, however well-intentioned it may be perceived, fits into this pattern. It reinforces the idea that solutions must always descend from above, from anointed figures or institutions, rather than be built from below through the solidarity of common people.

This does not mean the points raised about violence and obstruction are invalid. They are painfully real. But the analysis must go deeper. The “growing role of money in politics” he mentions is the lifeblood of the dictatorship’s patronage network. The “weakening public trust” is the direct result of a state that functions not for the people, but against them. To address these without naming the architecture that demands them is to treat a gangrenous wound with a scented bandage.

True change will never come from simply swapping one set of rulers for another, nor from hoping that existing hierarchies will develop a conscience. It comes from the slow, difficult work of building power of a different kind entirely: the power of communities organising to defend their land and labour; of residents assembling to govern their own neighbourhoods; of workers uniting across sectors; of a shared understanding that freedom is not given by kings or dictators, but taken and built by people who have decided they are no longer willing to be subjects.

The monarch’s call for peace ultimately rings hollow because it seeks peace within the cage. It asks for a more civilised captor. The urgent task for Ugandans is not to polish the bars of that cage, whoever holds the keys, but to imagine a world beyond cages altogether. The struggle is not for a better manager of the existing system, but for the courage to build something new from the ground up, where authority is earned through service and revoked by consent—a future where no single voice, royal or martial, can ever again claim to speak for the multitude.

The monarch’s call for peace ultimately rings hollow because it seeks peace within the cage. It asks for a more civilised captor. The urgent task for Ugandans is not to polish the bars of that cage, whoever holds the keys, but to imagine a world beyond cages altogether. The struggle is not for a better manager of the existing system, but for the courage to build something new from the ground up, where authority is earned through service and revoked by consent—a future where no single voice, royal or martial, can ever again claim to speak for the multitude.Of Republics and Realms: The Uncomfortable Contradiction of Crowned Commentary

At the heart of Uganda’s modern political identity lies a foundational, constitutional principle: we are a republic. This is not merely administrative detail; it is a deliberate rejection of the inherited, unaccountable authority epitomised by monarchy. It asserts, on paper at least, that sovereignty resides in the people, that citizenship confers equal standing, and that leadership is—theoretically—an elective office of service, not a birthright. Against this backdrop, the pronounced intervention of the Kabaka of Buganda into the tumult of a national electoral process presents not a helpful dialogue, but a fundamental constitutional and philosophical contradiction. It is the political equivalent of putting old wine into new bottles; the vessel may be modern, but the contents remain a ferment of hierarchical tradition.

The 1995 Constitution is unequivocal. Uganda is a unitary state whose sovereignty is derived from and vested in its citizens. The existence of cultural institutions, like the Buganda Kingdom, is explicitly framed within a non-political context, a fragile compromise from a contentious history. When the Kabaka issues a national call to the Electoral Commission and political actors, he steps beyond the cultural sphere. He unavoidably invokes the weight of a historical kingship to influence the affairs of a republic founded on its dismantling. This act, regardless of the merit of its message, subtly undermines the core republican ideal. It suggests that in moments of crisis, we should still look upwards to a throne for guidance, rather than inwards to our collective civic power or horizontally to each other. It reinforces a paternalistic politics where solutions are bestowed from above, rather than built from below.

This contradiction is particularly acute under the Museveni dictatorship. The regime has mastered the art of co-opting and managing all competing centres of influence. Traditional leaders are embraced, honoured, and granted ceremonial space precisely, so their authority can be neutralised or harnessed to lend legitimacy to the state’s own projects. The monarch’s critique of electoral violence, while valid, exists within a tolerated bracket. It voices a discontent the regime can afford to acknowledge because it is directed at the conduct of politics, not at the nature of power itself. The dictator understands the difference between a king asking for cleaner rules within the game, and the populace demanding an entirely new game. One is manageable dissent; the other is existential threat.

Furthermore, this intervention highlights a painful hypocrisy in our political architecture. We are lectured on electoral civility by a figure whose position defies the very essence of electoral principle—no one voted for him to hold authority. Meanwhile, a dictator who long ago abandoned any genuine pretence of democratic renewal presides over the very institutions being criticised. It creates a dizzying spectacle where unearned authority chides a dictator about the abuse of power, while both implicitly agree on one thing: that authority is the exclusive right of a privileged few to wield. The common Ugandan—the market woman, the boda rider, the nurse—is reduced to a spectator in a debate between different flavours of top-down control.

Furthermore, this intervention highlights a painful hypocrisy in our political architecture. We are lectured on electoral civility by a figure whose position defies the very essence of electoral principle—no one voted for him to hold authority. Meanwhile, a dictator who long ago abandoned any genuine pretence of democratic renewal presides over the very institutions being criticised. It creates a dizzying spectacle where unearned authority chides a dictator about the abuse of power, while both implicitly agree on one thing: that authority is the exclusive right of a privileged few to wield. The common Ugandan—the market woman, the boda rider, the nurse—is reduced to a spectator in a debate between different flavours of top-down control.The real damage lies in the erosion of the republican spirit. Every time a hereditary ruler is framed as a national moral arbiter, the muscle of true citizenship—the belief that ordinary people have the right and the capacity to directly shape their destiny—weakens. It distracts from the urgent work of building genuine, grassroots power: community assemblies, resilient mutual aid networks, trade unions with teeth, and coalitions that operate on the principle of direct participation and accountability. These are the structures that can challenge a dictatorship, not because they seek to replace the man on the throne in Entebbe with another, but because they seek to dismantle the very idea that society needs a throne to function.

The path forward for Uganda does not lie in harmonising the voices of monarchy and militarism. It lies in outgrowing them both. It requires a stubborn commitment to the radical notion embedded, yet stifled, in our republican claim: that power is not a crown to be worn or a gun to be held, but a shared responsibility to be exercised collectively. Our future depends not on heeding calls from palaces, but on finally listening to the quiet, powerful hum of ordinary people organising, cooperating, and refusing to be subjects any longer. The republic was meant to be that promise. It remains a promise to be seized, not from above, but from within and between us all.

Velvet Robes and Empty Harvests: On Inherited Privilege in a Working Republic

Beneath the gleaming crowns and the solemn echo of royal drums lies a quiet, persistent truth often obscured by ceremony and sentiment: there exists a class of individuals whose claim to authority, wealth, and public reverence stems not from any tangible contribution to the common good, nor from the expressed consent of the governed, but from the immutable accident of birth. This is the reality of a hereditary monarchy within a struggling republic. It embodies a principle starkly at odds with the daily labours of Uganda: that one can live, and live extraordinarily well, on the accumulated cultural capital and political compromises of the past, rather than on the productive work of the present. To examine this is not to disrespect culture, but to question a fundamental injustice. It brings to mind the old adage, “He who does not work, neither shall he eat,” a stark contrast to a system where one feasts first by virtue of lineage.

The institution in question is maintained by a triple foundation, each pillar revealing its detachment from the productive life of the nation. First, there is Historical Accident. Its position is a relic of pre-colonial structures, preserved and mutated through colonial indirect rule and post-colonial political bargaining. Its continuity is not a testament to ongoing, indispensable service, but to an enduring capacity to survive by adaptation to whatever central power holds the gun and the purse.

Second, Cultural Sentiment sustains it. This is its most powerful shield. Love for tradition, language, and history is profoundly human and legitimate. However, this affection is expertly transmuted into political capital. The deep, genuine connection people feel to their heritage is too often leveraged to legitimise the political and economic privileges of a single, pre-ordained family. The robe is velvet, soft, and familiar, making it harder to feel the weight of the burden it represents—a burden of unquestioned hierarchy in a land where every other citizen must earn their keep.

Second, Cultural Sentiment sustains it. This is its most powerful shield. Love for tradition, language, and history is profoundly human and legitimate. However, this affection is expertly transmuted into political capital. The deep, genuine connection people feel to their heritage is too often leveraged to legitimise the political and economic privileges of a single, pre-ordained family. The robe is velvet, soft, and familiar, making it harder to feel the weight of the burden it represents—a burden of unquestioned hierarchy in a land where every other citizen must earn their keep.Third, and most critically, its relevance is secured through Ongoing Political Deals with the Central State. The Museveni dictatorship, like regimes before it, understands the utility of traditional leaders. They are not rivals, but potential partners in management. By granting ceremonial recognition, cultural space, and often turning a blind eye to vast land holdings whose origins are mired in dispossession, the regime buys a measure of stability. It converts a potential centre of alternative power into a sympathetic, or at least neutralised, entity. The monarchy, in turn, secures its own survival and privileges by operating within boundaries the dictator finds non-threatening. This is a silent covenant of mutual preservation among elites, paid for by the sovereignty and resources that should belong to the people as a whole.

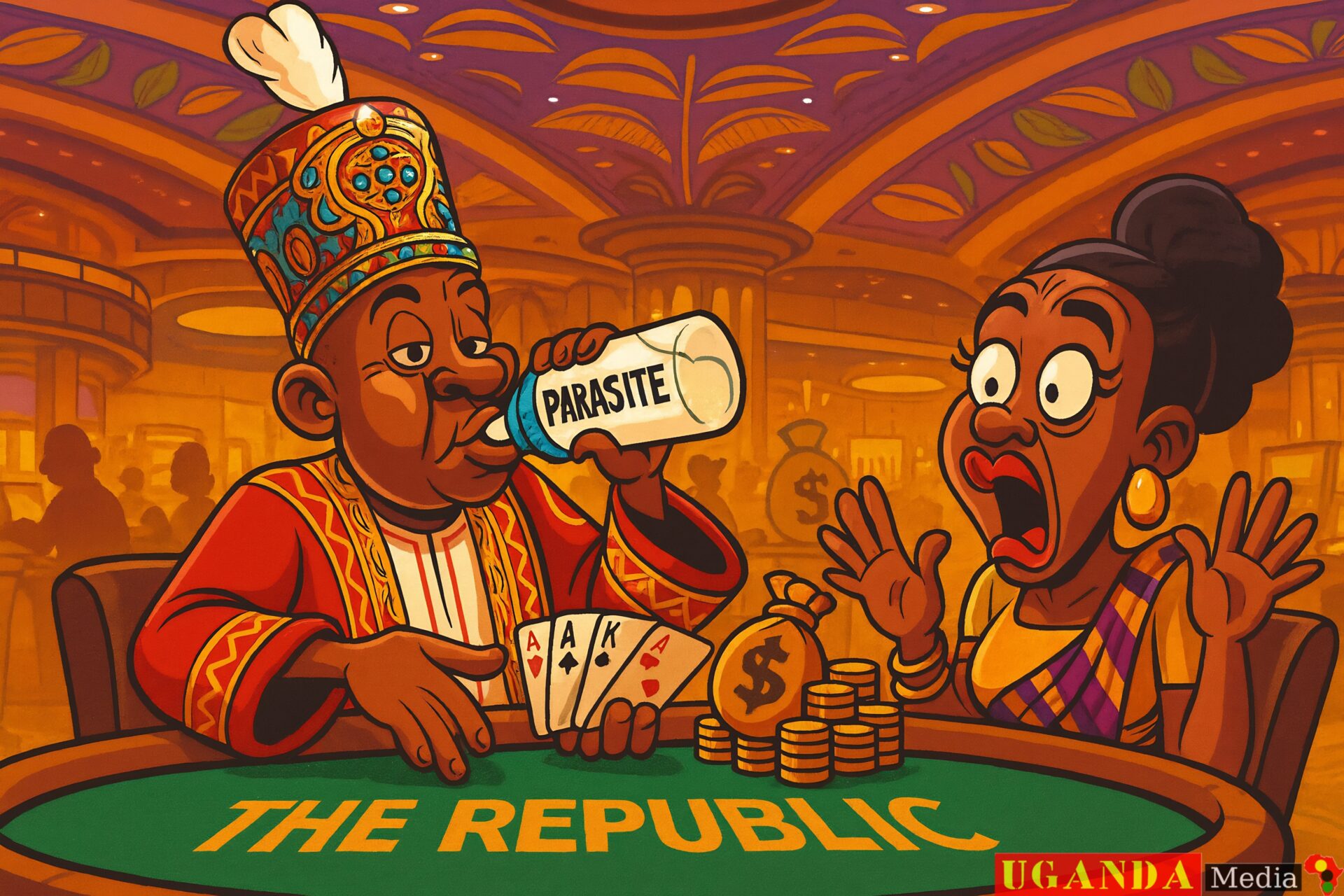

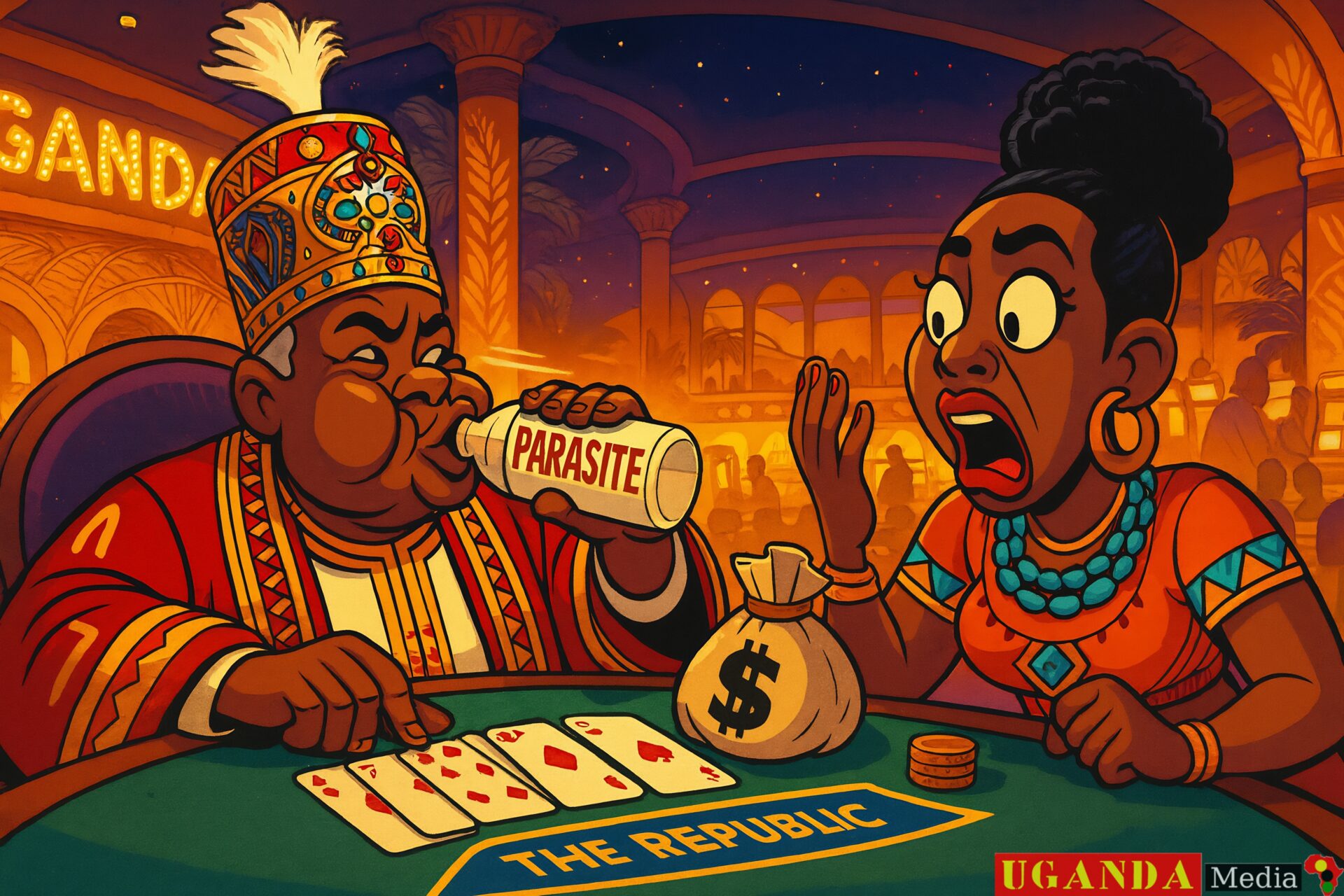

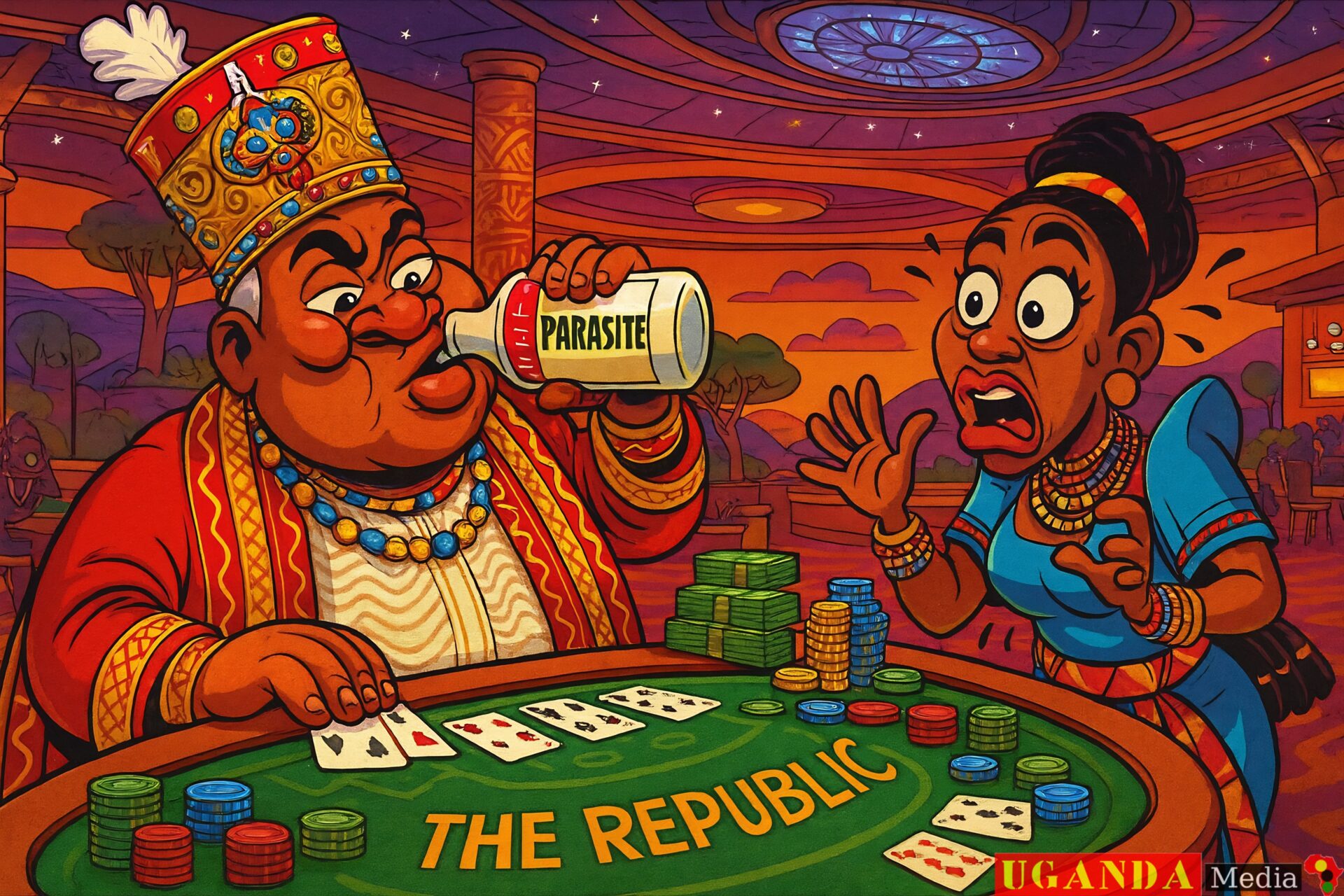

This arrangement creates a professional parasite class—not in the vulgar sense of laziness, but in the economic sense of an entity that extracts wealth and status without contributing to the generative, productive base of society. While teachers, nurses, farmers, and mechanics labour, often against impossible odds, to build and sustain the nation, this institution draws its sustenance from land rents, state-sanctioned cultural levies, and the soft power that attracts patronage. Its work is representational, not transformational; it manages sentiment, it does not dig latrines, heal the sick, or grow food. Its most visible product is pageantry, while Uganda’s needs are for justice, healthcare, and bread.

This dynamic is profoundly corrosive. It teaches a dangerous lesson: that the highest honour and comfort are bestowed by fate, not earned by merit or collective endeavour. It sits in stark, ugly contrast to the brutal economic reality faced by millions of Ugandans, for whom relentless work still guarantees neither security nor dignity. Furthermore, it provides a decorative, culturally-sanctioned mask for the very idea of unearned privilege, making it harder to challenge the same principle when it appears in the form of a dictator’s lifelong tenure or a corrupt official’s illicit wealth.

The alternative to this pageantry of inherited power is not a barren, culture-less world. It is a society where respect is earned through service, where leadership is accountable and recallable, and where the wealth of the land benefits those who work it. True culture is living, democratic, and built from the ground up—in cooperative farms, in community-owned workshops, in neighbourhood assemblies where every voice holds equal weight. It is the culture of the shared harvest, not of the solitary, gilded feast. To build a genuinely free Uganda requires moving beyond a politics that venerates either the crown or the gun, and instead, fostering a deep-rooted belief in our own collective power to create, govern, and thrive together, without masters or monarchs.

The Echo in the Palace: Why Elite Condemnation Rings Hollow

When the cattle herder in Karamoja is dispossessed by state-backed ranchers, when the market vendor in Kikuubo has her wares confiscated by authorities, or when the university student is dragged into a black van for a critical social media post, their reality defines true oppression. It is a raw, immediate experience of state power exerted without meaningful consent. Against this backdrop, a statement of concern from a palace, however elegantly worded, does not represent solidarity. It represents a conversation happening in another room entirely. This is the core of the issue: a critique of state violence delivered from a throne does not undermine the architecture of power; it merely decorates its walls. It is, as the old adage goes, a house divided against itself cannot stand—but here, the division is a theatrical performance within the same grand house of authority.

The recent commentary from the Kabaka regarding electoral violence and the conduct of state organs follows a familiar script. It identifies real wounds—the beatings, the obstructions, the weaponised law—yet its source transforms its meaning. This is not the collective roar of the dispossessed. It is, rather, an intra-elite discourse. It is one entrenched, unelected pillar of the nation’s hierarchical landscape addressing another: the militarised dictatorship. The subtext is not a fundamental challenge to the right of the state to monopolise violence and political control, but an appeal for that power to be exercised with more decorum. It is a plea for better management, not for the dismantling of the manager’s office.

This distinction is vital. Authentic criticism from below seeks to dismantle or radically transform the oppressive apparatus. It emerges from shared vulnerability and builds power through collective action—the neighbourhood assembly, the informal trade union, the community land defence. Its authority comes from the direct experience of injustice and the courage to name it without seeking a place at the table of the oppressor. In stark contrast, criticism from a traditional authority like the monarchy comes from a position of secured, if circumscribed, power. Its survival depends on a continuous, delicate negotiation with the very state it critiques. Its condemnation is therefore inherently limited, calibrated to chastise excesses while ultimately upholding the system that guarantees its own privileged existence.

This distinction is vital. Authentic criticism from below seeks to dismantle or radically transform the oppressive apparatus. It emerges from shared vulnerability and builds power through collective action—the neighbourhood assembly, the informal trade union, the community land defence. Its authority comes from the direct experience of injustice and the courage to name it without seeking a place at the table of the oppressor. In stark contrast, criticism from a traditional authority like the monarchy comes from a position of secured, if circumscribed, power. Its survival depends on a continuous, delicate negotiation with the very state it critiques. Its condemnation is therefore inherently limited, calibrated to chastise excesses while ultimately upholding the system that guarantees its own privileged existence.The Museveni dictatorship understands this dynamic perfectly. It can tolerate, and even quietly welcome, such reproof from a fellow elite institution. It serves a useful purpose: it creates a spectacle of democratic contention and moral oversight where little exists. It allows the regime to portray itself as part of a civilised debate among responsible leaders, all while the iron fist of the police and military remains unchanged. The monarch’s voice, in this grim theatre, becomes a pressure valve, subtly redirecting public anger into the channel of respectable appeal, thereby deflating the more dangerous potential of organic, grassroots resistance that recognises no authority but its own.

Ultimately, this performance obscures the only path to genuine liberation. The struggle against state violence is not won when a king urges a dictator to be kinder. It is advanced when ordinary people, in their workplaces, villages, and neighbourhoods, build networks of mutual aid and direct action that make the state’s coercive power irrelevant. It grows when they refuse to recognise the moral or political authority of any unaccountable figure, whether in military fatigues or royal robes, and instead cultivate their own capacity for self-governance. True solidarity is horizontal, born in the shared struggle of those who labour and suffer under the yoke. It is not, and can never be, a blessing bestowed from above. The future of Uganda will be written not by the dialogues between palaces and state houses, but by the quiet, determined organising of its people, learning to trust not in the voices of authority, but in their own collective voice.

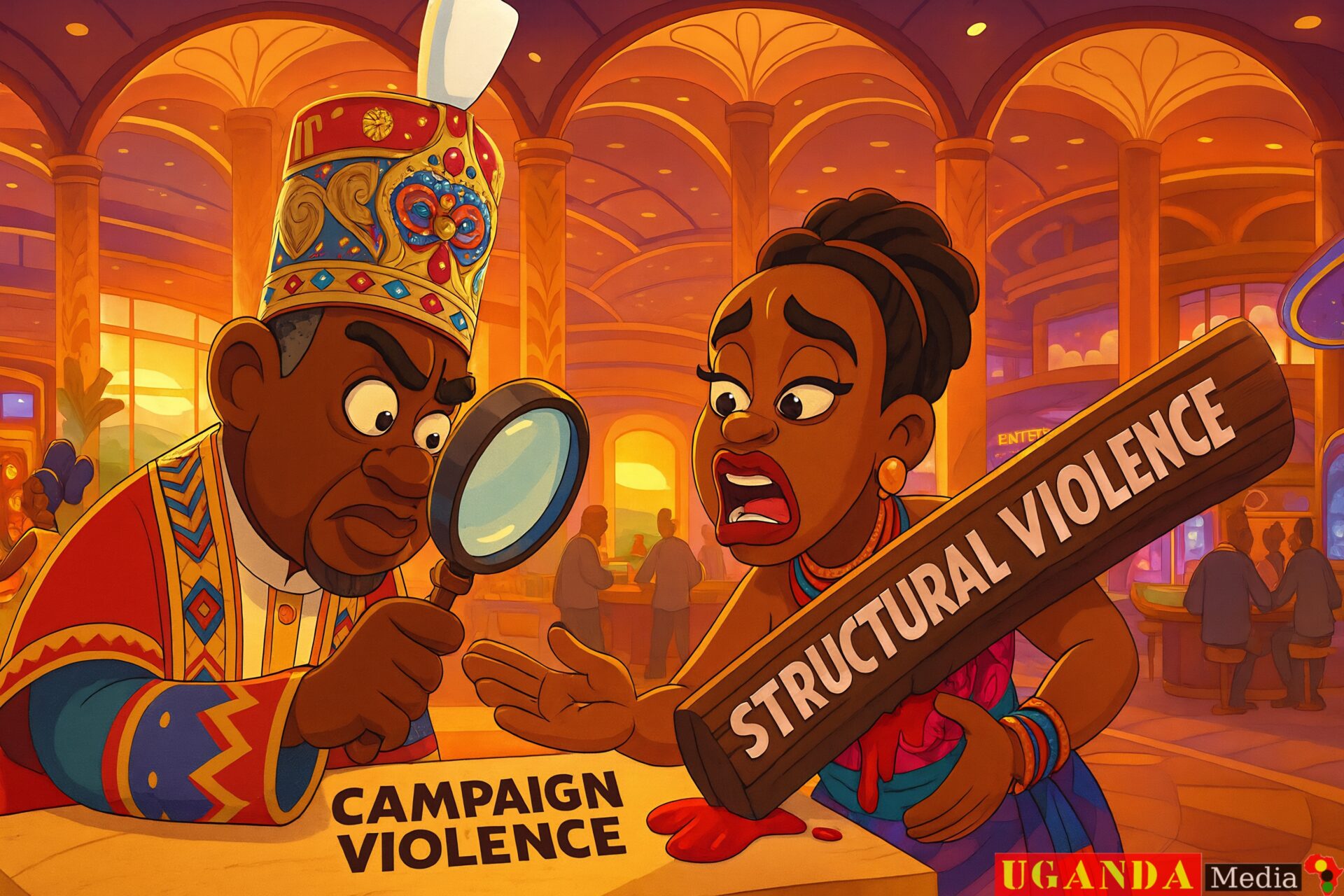

The Splinter and the Beam: On the Politics of Selective Outrage

In the tumult of a Ugandan election season, the spectacle of violence is undeniable. The scuffle at the rally, the blocked road, the activist bundled into a vehicle—these are vivid, televisable moments of rupture. They rightfully draw condemnation, including from elevated quarters. However, to focus solely on these visible fractures is to mistake the symptom for the disease. It is to fuss about the splinter in another’s eye while ignoring the beam in one’s own. The structural violence of the state—less photogenic but far more devastating—continues unabated, relying on this very selectivity of vision to perpetuate itself.

The condemnation of campaign brutality is valid, but its limitation is its purpose. By focusing exclusively on the excesses of the electoral period, the narrative implies that the state’s default mode is one of order and legitimacy, currently suffering a temporary lapse. This could not be further from the truth. The state, under the Museveni dictatorship, is itself a project of continuous, low-intensity violence against the populace. Its foundations are not law, but force; not service, but extraction.

The condemnation of campaign brutality is valid, but its limitation is its purpose. By focusing exclusively on the excesses of the electoral period, the narrative implies that the state’s default mode is one of order and legitimacy, currently suffering a temporary lapse. This could not be further from the truth. The state, under the Museveni dictatorship, is itself a project of continuous, low-intensity violence against the populace. Its foundations are not law, but force; not service, but extraction.Consider the deeper, silent violences that go routinely unchallenged in such elite discourses:

The violence of endemic corruption is not a mere theft of funds. It is violence that denies hospitals medicines, leaves schools without roofs, and abandons roads to ruin. It systematically steals the future from millions, condemning them to preventable poverty. It is a daily, quiet war on human dignity and potential.

The violence of land dispossession, often facilitated by state actors and opaque investors, is not a simple property transaction. It is a visceral uprooting of lives, histories, and communities. It destroys generations of livelihood and culture, creating internal refugees in their own country, all while the legal machinery of the state is wielded to sanctify the theft.

The violence of economic inequality, engineered by a crony capitalist system, is a structural condemnation. It is the violence of watching a child’s potential stunted by malnutrition while obscene wealth flaunts itself in sealed-off estates. It is the policy-driven denial of a living wage, the calculated inflation that erodes survival, ensuring the majority remain in a permanent state of precarious toil.

The daily tyranny of a militarised police force extends far beyond campaign rallies. It is the constant, looming threat at every protest over service delivery, the intrusive patrol through poor neighbourhoods, the institutionalised brutality in cells and safe houses. This is the bedrock of control, normalising fear and teaching citizens that their bodies and assemblies are not truly their own.

A critique that remains silent on these foundational forms of violence is, ultimately, a form of complicity. It treats the political system as a basically sound engine that occasionally overheats, rather than a machine designed for predation. For the hereditary monarch to condemn the splinter of electoral violence while ignoring the beam of structural violence is a politically calculated silence. It allows him to posture as a moral voice without threatening the core power dynamics from which his own institution benefits. It is a condemnation that suits the dictatorship as well, for it quarantines criticism to a specific, manageable event—the election—while leaving the everyday machinery of domination untouched.

True justice begins when we shift our gaze from the spectacular splinter to the oppressive beam. It starts when the market vendors, the landless farmers, the overworked nurses, and the unemployed graduates name their condition not as misfortune, but as the direct result of systemic violence. The path to liberation lies not in appeals for gentler conduct during elections, but in the collective, grassroots building of power that can resist the state’s daily violations and create alternative, equitable means of organising society from the ground up. It demands a condemnation that is total, fearless, and rooted not in palace halls, but in the shared reality of the oppressed.

The Captive Referee: On Appealing to a Compromised Arbiter

There is a particular, piercing irony when a figure of considerable stature publicly implores a discredited institution to finally act with integrity. The recent call for the Electoral Commission (EC) to ensure a neutral playing field is precisely such a moment. Its poignancy lies not in its novelty, but in its tragic redundancy. It underscores the very crisis it seeks to remedy: the EC is not an independent referee but a captured instrument, widely and correctly perceived as an integrated component of the Museveni dictatorship’s machinery for retaining power. To appeal to it for impartiality is, as the old adage goes, akin to putting the fox in charge of the henhouse and then pleading with it for a fair count of the chickens.

The EC’s constitutional mandate paints a picture of a stern, impartial guardian of democratic will. In practice, its history is a chronicle of partisan alignment. Its capture is not a sporadic failure but a systemic design. From the controversial composition of its leadership—appointed through a process controlled by the executive—to its consistent pattern of decisions that disproportionately burden and penalise opposition while tolerating the transgressions of the regime, the evidence is overwhelming. It functions not as an auditor of the process, but as its stage manager, ensuring the theatrical performance of an election proceeds on script towards a pre-ordained conclusion.

This manifests in several key ways: the selective and often chaotic enforcement of campaign guidelines; the persistent issues with voter register integrity that disproportionately affect areas of suspected opposition strength; the legalistic obstruction of meaningful observation; and the swift dismissal of legitimate grievances while meticulously pursuing technical violations against regime critics. The EC’s primary role appears not to be the facilitation of a genuine contest, but the administration of a complex ritual that bestows a veneer of legitimacy upon an entrenched autocracy. It converts raw political power into a seemingly legal and procedural fact.

This manifests in several key ways: the selective and often chaotic enforcement of campaign guidelines; the persistent issues with voter register integrity that disproportionately affect areas of suspected opposition strength; the legalistic obstruction of meaningful observation; and the swift dismissal of legitimate grievances while meticulously pursuing technical violations against regime critics. The EC’s primary role appears not to be the facilitation of a genuine contest, but the administration of a complex ritual that bestows a veneer of legitimacy upon an entrenched autocracy. It converts raw political power into a seemingly legal and procedural fact.Therefore, an appeal for this body to suddenly become “active and neutral” is a profound contradiction. It asks the tool to stop being useful to its wielder. The plea, however dignified its source, inadvertently shines a stark light on this captured nature. It highlights a public truth so glaring it requires royal address: the institution tasked with guaranteeing fairness is itself the cornerstone of the unfairness. This does not invalidate the condemnation of violence and obstruction, but it frames them as symptoms of a deeper pathology. The beatings and blockades are the crude, visible enforcement; the EC’s bias is the sophisticated, legalistic engineering of the same outcome—the negation of popular will.

The danger in such appeals is that they can inadvertently reinforce the very legitimacy they seek to critique. By engaging the EC as a credible arbiter in need of moral exhortation, the discourse concedes to its authority. It perpetuates the fiction that change can come from within these compromised institutions through appeals to conscience, rather than through a sober recognition that they are beyond reform because their purpose is not democratic. It directs energy towards convincing the fox to be vegetarian, rather than towards building a new, community-controlled coop.

The path forward lies not in the forlorn hope that captured institutions will liberate themselves. It is found in the slow, diligent work of building parallel structures of accountability and decision-making from the ground up. It is in community assemblies that monitor local conditions, in people’s tribunals that document state violence, and in the cultivation of a collective consciousness that understands true power and legitimacy spring from popular organisation, not from the seals and pronouncements of a commission serving a dictator. The future of Ugandan democracy will not be certified by the EC; it will be built, despite it, by the unwavering resolve of ordinary people to govern themselves.

The Gilded Lectern: On Wealth, Land, and the Diversion of Discourse

To witness an institution founded upon centuries of accumulated wealth and sustained by a system of land ownership that has bred profound social strife stand before the nation and decry the corrosive influence of money in politics is to witness a masterclass in misdirection. It is a spectacle that brings to mind the adage of the pot calling the kettle black, a performance that draws the public’s eye towards a real but secondary ill, while deftly shielding from scrutiny an even greater source of inequity. The critique of campaign finance, while valid in its own right, becomes a strategic diversion when its source is a monarchy whose very existence is a monument to unearned economic privilege and a primary engine of Uganda’s most enduring injustices.

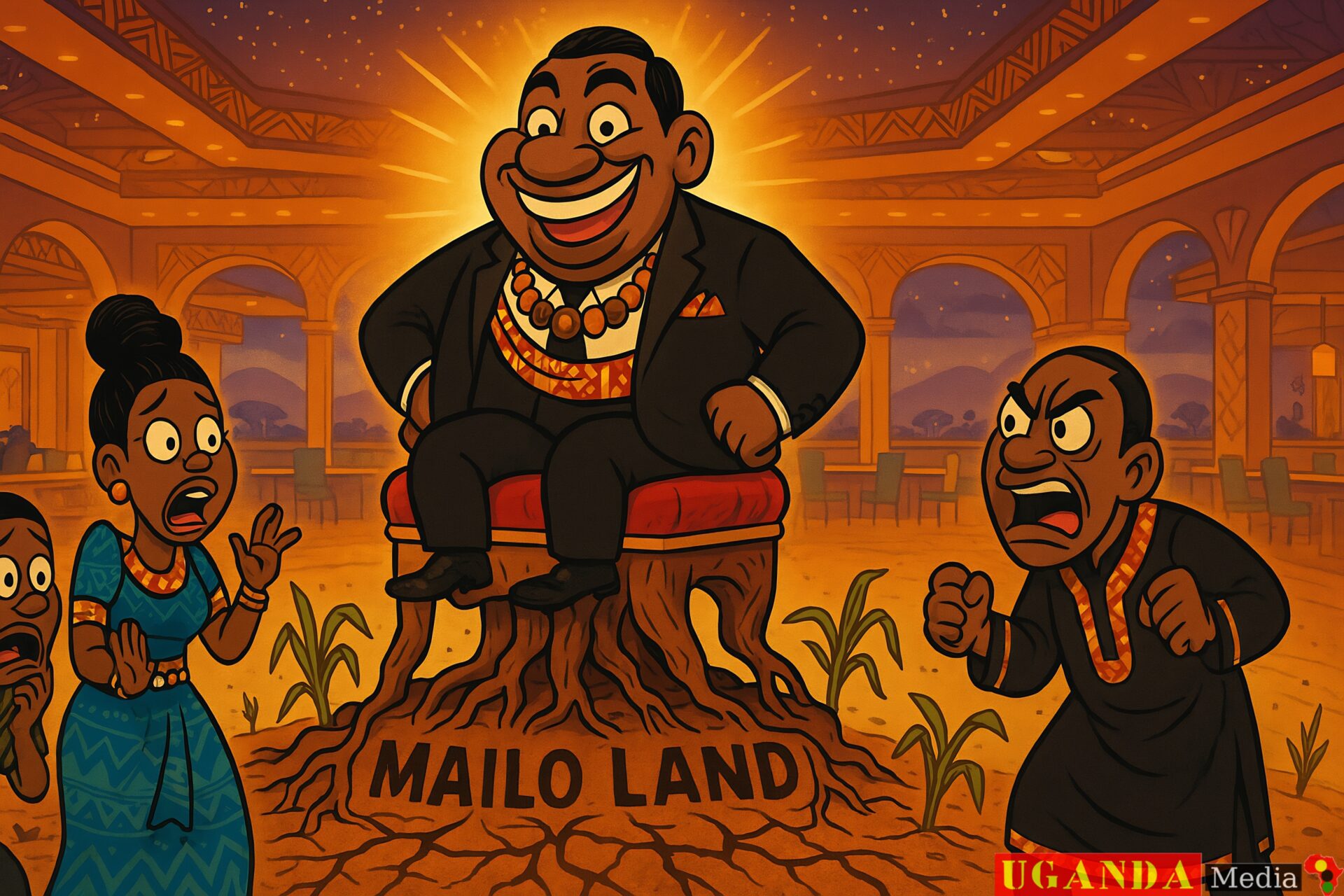

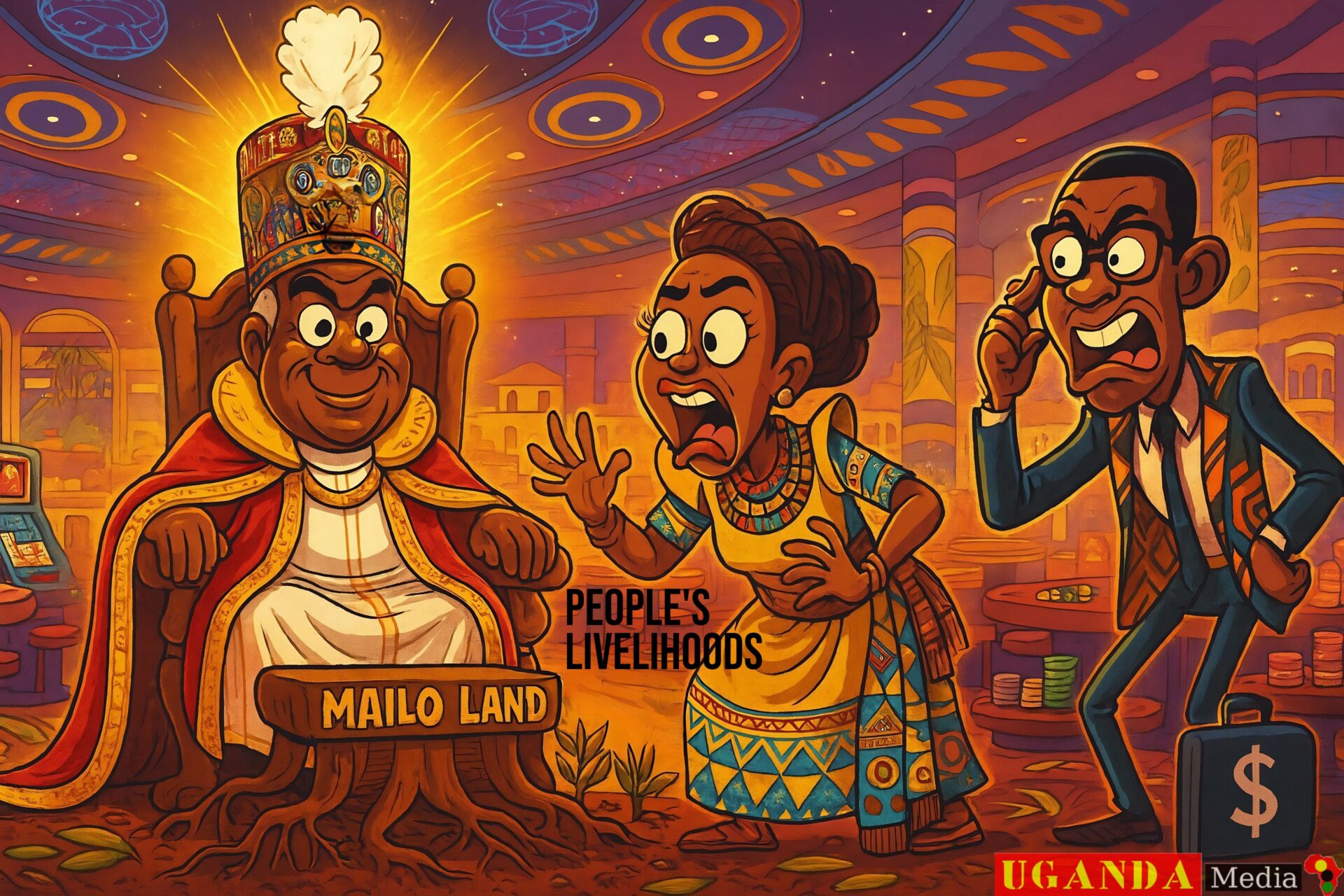

The monarchy’s wealth is not a passive inheritance; it is an active, structural force in the Ugandan economy. Its foundation is the Mailo land system, a colonial relic that created a category of landowners with near-absolute rights over territory and the people living on it. This system is not a historical footnote but a present-day source of immense conflict, dispossession, and human suffering. Across the Buganda region, and by extension influencing national patterns, Mailo land is the seedbed for countless evictions, protracted legal battles, and a pervasive sense of tenure insecurity for the bona fide occupants and tenants who have worked the soil for generations. The institution thus profits from—and is intrinsically tied to—a form of structural violence that pits landlord against tenant, paper title against ancestral right, and privilege against subsistence.

The monarchy’s wealth is not a passive inheritance; it is an active, structural force in the Ugandan economy. Its foundation is the Mailo land system, a colonial relic that created a category of landowners with near-absolute rights over territory and the people living on it. This system is not a historical footnote but a present-day source of immense conflict, dispossession, and human suffering. Across the Buganda region, and by extension influencing national patterns, Mailo land is the seedbed for countless evictions, protracted legal battles, and a pervasive sense of tenure insecurity for the bona fide occupants and tenants who have worked the soil for generations. The institution thus profits from—and is intrinsically tied to—a form of structural violence that pits landlord against tenant, paper title against ancestral right, and privilege against subsistence.For this same institution to then lament the “growing role of money in politics” and the “weakening of public trust” is a breathtaking contradiction. It speaks of the symptom—the flash of cash during elections—while being part of the disease: the normalization of vast, unaccountable concentrations of wealth and the treatment of land and people as revenue streams. The political bribes and patronage it decries are merely the liquid, transactional expressions of the same logic of ownership and extraction that its own estates represent in solid, unmovable form. The dictator’s regime employs mobile money and bags of cement to buy allegiance; the monarchy rests upon square miles of territory and the rents drawn therefrom. Both systems undermine democratic will, one by purchasing votes, the other by enforcing a hierarchy where many are born tenants on another’s nation.

This critique from the palace is, therefore, a profound diversion. It redirects public anger away from a critical examination of all forms of oligarchic power—traditional and militarist—and focuses it solely on the more visible vulgarities of electoral politics. It allows the monarchy to pose as a guardian of political purity, even as its economic foundation contributes directly to the economic despair that makes voters susceptible to petty bribery in the first place. The message becomes: “Look at the dirty money changing hands over there, not at the settled, sanctified wealth sitting here.”

A genuine struggle for equity must see this connection clearly. The fight for a just politics is inseparable from the fight for a just economy. It requires challenging not only the dictator’s theft of the treasury, but also the entire architecture of inherited privilege that condemns millions to landlessness and precarity. True progress lies in envisioning and building alternatives: community-controlled land trusts, cooperative models of agriculture and housing, and economies organized around mutual aid and need, rather than rent and royal prerogative. It means recognising that the most corrosive money in politics is often that which is already cemented in the ground, legitimised by history, and shielded from democratic challenge by the velvet robes of tradition. Until that is addressed, calls for cleaner elections will remain little more than a soothing hymn, sung from a pulpit built on disputed land.

A genuine struggle for equity must see this connection clearly. The fight for a just politics is inseparable from the fight for a just economy. It requires challenging not only the dictator’s theft of the treasury, but also the entire architecture of inherited privilege that condemns millions to landlessness and precarity. True progress lies in envisioning and building alternatives: community-controlled land trusts, cooperative models of agriculture and housing, and economies organized around mutual aid and need, rather than rent and royal prerogative. It means recognising that the most corrosive money in politics is often that which is already cemented in the ground, legitimised by history, and shielded from democratic challenge by the velvet robes of tradition. Until that is addressed, calls for cleaner elections will remain little more than a soothing hymn, sung from a pulpit built on disputed land.The Chameleon’s Dance: Survival and Compromise in the Shadow of Power

The trajectory of the Buganda monarchy through Uganda’s turbulent history is not a saga of steadfast principle, but a masterful study in adaptive survival. Its relationship with successive central states reveals a recurring pattern of shifting compromise and tactical alliance, a relentless pursuit of self-preservation that has frequently fragmented the potential for a broader, unified challenge to oppression. This is a history less of crowns and thrones, and more of calculated handshakes and quiet understandings, a practice of dancing with the devil without ever fully being consumed, yet never truly breaking free from the infernal pact.

The foundations were set during colonialism. The British, through the infamous 1900 Agreement, transformed the Kabaka from a sovereign ruler into a subordinated “native authority” within a larger colonial framework. The monarchy, in essence, became a critical intermediary—a instrument of indirect rule. It administered on behalf of the Crown, collecting taxes and enforcing order, in exchange for the preservation of a diluted form of its own status and significant control over land (the Mailo system). This was the original, defining compromise: survival and limited privilege purchased with collaboration, cementing a hierarchy that benefited both coloniser and traditional elite at the expense of the ordinary peasantry.

At independence, this pattern of pragmatic alliance continued. The monarchy’s political manoeuvring, seeking to maximise Buganda’s federal autonomy, became entangled in the partisan conflicts of the early republic. Its actions, while aimed at protecting its own interests, often exacerbated national divisions and ultimately contributed to the crises that led to its abolition by the Obote regime in 1966. Its restoration in 1993 under the Museveni dictatorship was itself the fruit of a new, and perhaps most definitive, compromise.

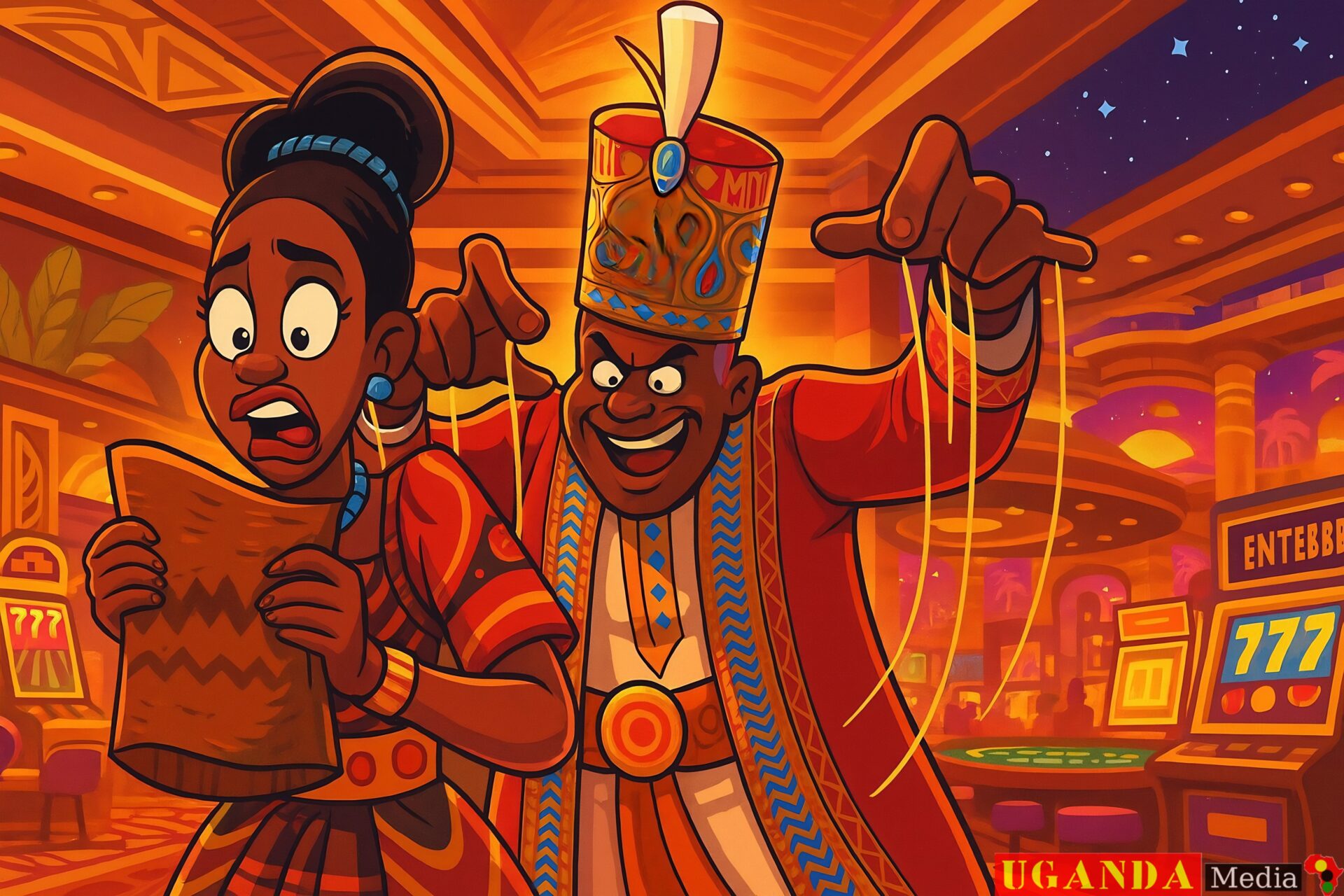

The current understanding between the monarchy and the regime is a modern incarnation of this historical dance. The dictatorship, needing to consolidate control over a historically significant and populous region, offered the restoration of the kingdom’s cultural institutions—but strictly without federal political power. In return, the monarchy has largely operated within the unspoken boundaries set by the state. It is permitted to celebrate culture, to engage in development rhetoric, and to occasionally offer measured, procedural critiques of governance—such as decrying electoral violence—but it stops profoundly short of endorsing or catalysing any genuine, mass-based movement that might threaten the regime’s fundamental hold on power.

The current understanding between the monarchy and the regime is a modern incarnation of this historical dance. The dictatorship, needing to consolidate control over a historically significant and populous region, offered the restoration of the kingdom’s cultural institutions—but strictly without federal political power. In return, the monarchy has largely operated within the unspoken boundaries set by the state. It is permitted to celebrate culture, to engage in development rhetoric, and to occasionally offer measured, procedural critiques of governance—such as decrying electoral violence—but it stops profoundly short of endorsing or catalysing any genuine, mass-based movement that might threaten the regime’s fundamental hold on power.This historical continuum of alliance and compromise has had a profound cost: the consistent undermining of a radical, unified people’s movement. By presenting itself as the primary, legitimate custodian of Buganda’s interests, the monarchy has often channelled legitimate popular grievance into petitions for royal restoration or regional autonomy, rather than into a broader coalition with the oppressed across Uganda. It has fostered a politics of identity and patronage that divides the landless peasant in Buganda from the landless peasant in Acholi or Teso, obscuring their shared class reality under the banner of traditional loyalty. When the choice is framed as loyalty to the crown or loyalty to a radical political alternative, the energy for a transformative project that transcends both is dissipated.

Thus, the monarchy’s historical role has been that of a sophisticated buffer. It absorbs and moderates discontent, negotiates its own space with the central authority of the day, and in doing so, helps to prevent the coalescence of a bottom-up, pan-Ugandan struggle for true emancipation. Its survival strategy is rooted in the very state system it sometimes gently critiques, making it inherently incapable of challenging that system’s foundations. True liberation for the people of Uganda, therefore, requires seeing beyond the cyclical dances of power between palace and state house. It demands building solidarity on the basis of shared material struggle—the fight for land, dignity, and freedom from all forms of coercive authority—recognising that the most enduring chains are often those polished by tradition and sanctified by a history of convenient deals.

The Vertical Funnel: How Royal Mediation Fractures People’s Power

When a community facing eviction from their ancestral land, or a group of workers denied a living wage, or the youth confronting a future without prospects, look for a channel to voice their anguish, the direction they are encouraged to look matters profoundly. They can look to each other, recognising a shared plight with others suffering across the nation, or they can look upward, to a figure of pre-ordained authority. The recent royal intervention, by presenting the monarchy as a moral arbiter for political grievances, powerfully reinforces the latter, vertical dynamic. This process acts as a social and political funnel, channelling diffuse, horizontal discontent into a narrow, vertical appeal for elite mediation. In doing so, it actively undermines the very solidarity needed for transformative change, embodying the truth that “united we stand, divided we fall”—where division is achieved not only by repression, but by the respectful diversion of grievance.

Horizontal solidarity is the recognition of common cause between the tenant farmer in Mubende, the street vendor in Jinja, and the unemployed graduate in Gulu. It is built on the understanding that their different struggles—against land grabs, punitive city ordinances, and a closed economic system—are threads of the same fabric: a system designed to extract labour and wealth while offering only insecurity in return. This solidarity is built slowly, through direct interaction, shared campaigns, and the concrete practice of mutual aid, creating networks of support that operate independently of state or traditional approval.

The interposition of a royal figurehead, however, disrupts this organic process. It teaches people that the proper, respectable route for their anger is not lateral organisation with their peers, but a vertical petition to a higher, culturally-sanctioned authority. The message, however subtly conveyed, is that legitimacy and resolution flow downward from recognised centres of heritage, not upward from collective will. This converts a potentially radical class consciousness into a supplicant cultural loyalty. The peasant in Buganda is encouraged to see their plight primarily as a Buganda issue, to be relayed through the Kabaka’s office, rather than as Ugandan workers’ and dwellers’ issue to be solved in concert with the peasant in Acholi or the fisherman in Busoga.

This vertical funnel is exceptionally convenient for all established powers. For the monarchy, it reinforces its continued relevance as the indispensable conduit for its people’s concerns. For the Museveni dictatorship, it is a perfectly manageable form of dissent. A grievance delivered through royal channels is, by definition, framed within the existing architecture of power. It becomes a negotiable issue between elites, rather than a foundational challenge from below. It atomises resistance, keeping it contained within ethnic or regional silos, preventing the emergence of a broad-based, issue-focused movement that could unite people across traditional divides on the basis of shared material needs.

This vertical funnel is exceptionally convenient for all established powers. For the monarchy, it reinforces its continued relevance as the indispensable conduit for its people’s concerns. For the Museveni dictatorship, it is a perfectly manageable form of dissent. A grievance delivered through royal channels is, by definition, framed within the existing architecture of power. It becomes a negotiable issue between elites, rather than a foundational challenge from below. It atomises resistance, keeping it contained within ethnic or regional silos, preventing the emergence of a broad-based, issue-focused movement that could unite people across traditional divides on the basis of shared material needs.The result is a weakened populace. Energy that could be spent building community councils, forming independent unions, or creating cooperative land trusts is instead spent awaiting a benediction or a statement from the palace. The profound power that comes from discovering one’s own agency alongside others is sacrificed for the fleeting hope of an endorsement from above.

True emancipation begins when people break this vertical habit. It starts when they turn from the palace and the state house towards each other, realising that their combined strength, knowledge, and numbers far outweigh the symbolic power of any throne. It is found in the quiet, determined work of building institutions of direct democracy and mutual support that owe nothing to hereditary privilege or militarised authority. The future of Uganda depends not on which elite speaks for the people, but on the people finally speaking—and acting—for themselves, in one united, resonant voice that needs no royal amplifier.

The Gentleman’s Agreement: How ‘Civility’ Becomes a Tool of Control

In the face of the riot shield, the barking dog, and the blunt instrument of state power, a familiar and seemingly reasonable appeal often arises: the call for ‘civility’. It is a demand for order, for respectful dialogue, for playing by the rules. Yet, when issued by those who oversee the machinery of violence, or by intermediaries who benefit from the status quo, this appeal is rarely neutral. It transforms into a sophisticated trap, a means of blaming the victim for the violence of the executioner. It polices not actions, but the very right to resist, ensuring dissent remains within confines that pose no real threat to the powerful.

The concept of civility is not an absolute good; it is a social construct, and its definition is invariably controlled by those in authority. Under the Museveni dictatorship, ‘civility’ is a moving target defined by the state’s own interests. A peaceful, unapproved assembly is deemed ‘uncivil’ because it violates an arbitrary statute. A raised voice against injustice is ‘incitement’. The state and its agents operate within a framework where they alone hold a monopoly on defining both the law and the acceptable manner of its critique. They can break their own rules—dissolving gatherings with brutality, imprisoning without charge—while simultaneously wielding ‘civility’ as a cudgel against those who dare to protest their condition. This is the essence of the trap: it demands that the oppressed fight on a tilted playing field, using etiquette manuals while their opponent uses batons.

The concept of civility is not an absolute good; it is a social construct, and its definition is invariably controlled by those in authority. Under the Museveni dictatorship, ‘civility’ is a moving target defined by the state’s own interests. A peaceful, unapproved assembly is deemed ‘uncivil’ because it violates an arbitrary statute. A raised voice against injustice is ‘incitement’. The state and its agents operate within a framework where they alone hold a monopoly on defining both the law and the acceptable manner of its critique. They can break their own rules—dissolving gatherings with brutality, imprisoning without charge—while simultaneously wielding ‘civility’ as a cudgel against those who dare to protest their condition. This is the essence of the trap: it demands that the oppressed fight on a tilted playing field, using etiquette manuals while their opponent uses batons.In Uganda, this dynamic plays out with cruel clarity. The small-scale trader whose kiosk is demolished by a KCCA enforcement operation is expected to seek ‘civil’ redress through costly, protracted courts. The community facing violent land eviction by private militia, often with state complicity, is urged to ‘dialogue’ with the very investors who deployed the guns. The student who speaks out risks not only arrest but societal chastisement for being ‘disrespectful’ or ‘unruly’. The demand for civility, in these contexts, becomes a demand for acquiescence. It pathologises righteous anger and reframes systemic violence as a mere breakdown in polite conversation.

For traditional institutions like the monarchy, aligning with this call for civility is a way to position themselves as responsible stewards above the fray. Yet, by urging ‘civil’ conduct within a fundamentally uncivil and unjust system, they inadvertently reinforce that system’s boundaries. They lend their moral weight to the idea that the problem is one of conduct rather than structure, of harsh methods rather than illegitimate power. It is a politics that prioritises the comfort of the privileged—who are never at the receiving end of state brutality—over the urgency of the oppressed.

True resistance cannot be bound by the etiquette manuals written by the oppressor. The struggle for justice is, by its nature, disruptive. It must be. It confronts a disorder so normalized—the disorder of hunger, of displacement, of fear—that only a determined, ungovernable assertion of human dignity can hope to challenge it. The energy of the people, when organised horizontally from below, will find its own legitimate forms of expression, from strikes and boycotts to mass civil disobedience and the creation of parallel, community-based systems of support. These actions may be labelled ‘uncivil’ by a dictatorship and its beneficiaries, but they are the authentic language of the unheard.

Ultimately, liberation will not be won by learning to protest more politely. It will be won by recognising that the demand for ‘civility’ is too often a demand for surrender, and by building independent power that is bold enough to disrupt the peace of the powerful in order to build a just peace for all.

The Managed Arena: When Dispute is a Feature, Not a Bug

The frequent, fraught encounters between opposition groups and the state’s security apparatus are often presented in public discourse as a series of unfortunate incidents—spontaneous clashes arising from overzealousness or poor planning. This is a profound misreading. These disputes are not anomalies in an otherwise open system; they are the predictable and inevitable symptoms of a rigidly controlled political order. The regime of dictator Museveni does not seek to eliminate political competition outright; it meticulously engineers it, permitting it only within a narrow, non-threatening arena whose walls are patrolled by police and whose rules are arbitrarily enforced by a partisan electoral commission. It is a system built on the principle of giving someone enough rope to hang themselves, where the illusion of contest is maintained only to justify the subsequent disciplinary action against those who dare to stretch the boundaries.

The state under the current dictatorship has perfected a model of managed political participation. Opposition is not illegal, but it is rendered perpetually precarious. A detailed, often opaque, framework of regulations—covering public assemblies, campaign schedules, and speech—creates a labyrinth of potential offences. This allows the regime to maintain a veneer of legality while granting itself infinite discretionary power to police, disrupt, and dismantle any activity it deems to have exceeded its unilaterally defined limits. The goal is not to create a level playing field, but to design a field where the state holds all the goalposts and can move them at will.

The specific clashes involving the National Unity Platform are a textbook manifestation of this design. Their rallies are not disrupted because they are uniquely unlawful, but because their energy, their popular mobilisation, and their challenge to the established narrative represent a breach of the unspoken contract. The contract stipulates that opposition must remain a manageable, elite affair, never spilling over into a genuine, mass-based movement that threatens the underlying distribution of power and wealth. When a political force shows signs of building that kind of horizontal, popular connection, it crosses from tolerated opposition into perceived insurrection, and the state’s mechanisms of control switch from observation to active suppression.

This transforms the security forces from neutral guardians of public order into the enforcement wing of a political project. Their role is to act as the literal boundary-keepers of the permitted political arena. The violence, the blockades, and the arrests are not a failure of the system; they are its core functionality. They serve as a stark, public reminder of the consequences of stepping beyond the approved margins. It is a performance of power intended to demoralise supporters, exhaust resources, and telegraph a clear message to all other would-be challengers about the costs of substantive competition.

Therefore, to focus solely on the drama of these clashes is to miss the underlying architecture. The struggle is not about obtaining a permit for a rally or securing a fair hearing from the Electoral Commission. The struggle is against the very logic of a managed, bounded politics where the state grants conditional privileges to dissent. True political emancipation lies not in winning a better deal within this arena, but in recognising the arena itself as a cage. It resides in the quiet, determined work of building power outside of it—in communities, workplaces, and neighbourhoods—where people exercise direct control over the decisions that affect their lives, rendering the state’s violent theatre of managed politics increasingly irrelevant. The symptom is the clash in the streets; the disease is the dictatorship’s monopoly on the very definition of legitimate politics.

The Managed Dissident: How Official Opposition Stifles Political Imagination

The precise, relentless targeting of a prominent musical artist turned political figure is frequently portrayed as the regime’s visceral reaction to a singular threat. However, a more in-depth analysis suggests a more calculated, systemic function. This pattern of focused repression follows a longstanding playbook for authoritarian control: the management of dissent through the creation and containment of an ‘official’ opposition. This process does not merely aim to neutralise one individual, but to actively shape the entire political landscape by channelling discontent into a recognisable, and ultimately manageable, form. It is a strategy of feeding the tiger just enough to keep it in its cage, ensuring a dangerous energy is both visible and safely confined, preventing more unpredictable and transformative forces from emerging.

Dictator Museveni’s regime, like many before it, understands that the total eradication of dissent is impossible and often counterproductive. A more effective method is to selectively anoint and corral it. By concentrating its legal, security, and rhetorical fire on a primary, high-profile challenger, the regime achieves several critical objectives. First, it creates a clear, singular narrative for both domestic and international consumption: politics is framed as a binary contest between the incumbent and one principal rival. This simplistic framing marginalises a multitude of other grievances, ideologies, and potential movements that fall outside this manufactured duel.

Secondly, this focused containment funnels popular frustration into what appears to be the only viable channel of resistance. It directs energy, resources, and hope towards a conventional electoral challenge operating within the very state institutions—the parliament, the courts, the Electoral Commission—that are fundamentally configured to uphold the regime. This strategic channelisation actively stifles the development of more diverse, grassroots, and radical political imaginations. It sidelines questions of economic redistribution, community-owned resources, workers’ control, or alternative models of social organisation that reject the centralised state entirely. The debate becomes narrowed to who should hold the reins of the existing, oppressive machinery, rather than how to dismantle or replace that machinery altogether.

Furthermore, the spectacle of the ‘contained dissident’—perpetually harassed but never eradicated—serves a demoralising and cautionary function. It demonstrates the high personal cost of headline political challenge, while simultaneously implying its ultimate futility within the system’s rigged confines. This spectacle can exhaust the political will of a populace, making the slower, less glamorous work of building autonomous community power from the ground up seem less appealing. Why organise a community land cooperative when the national drama revolves around a presidential candidate’s rally permit?

The true threat to any authoritarian system is not a rival candidate playing a slightly different tune on the same instrument; it is the sound of entirely new instruments being crafted, of communities learning to orchestrate their own affairs without reference to the state’s baton. By maintaining a high-profile ‘official’ dissent, the regime effectively places a ceiling on political imagination. It ensures that for many, the horizon of the possible ends at the next disputed election, rather than encompassing the creation of directly democratic village assemblies, syndicates of informal workers, or federations of tenant farmers who could wield genuine, unconcentrated power.

Thus, the persecution of a prominent figure is not merely an attempt to silence one man. It is a method of crowd control for political thought. It seeks to ensure that resistance marches down a broad, well-paved road that leads to a fortified gate, rather than dispersing into a thousand pathways through the brush, paths that could eventually converge somewhere the dictatorship’s maps do not reach. The struggle for Uganda’s future, therefore, lies as much in defying this managed political imagination as it does in confronting the dictator’s security apparatus, for the former is the ideological prison that makes the latter seem like the only reality.

The Calculated Calm: Survival as Strategy in a Republic of Tension

In the fraught atmosphere of a Ugandan election cycle, where the state’s capacity for violence is palpable and public trust is a scarce commodity, the emergence of a voice calling for peace and impartiality appears as a beacon of reason. Yet, when that voice emanates from a hereditary throne within a republican constitutional order, its function must be scrutinised beyond its surface morality. This intervention is a refined exercise in institutional survival. It represents a strategic manoeuvre to present the monarchy as the indispensable, stabilising moral centre in a nation perpetually pitched towards chaos, thereby securing its continued relevance, political space, and material assets. It is the art of keeping one’s head when all about are losing theirs, and making sure everyone notices you doing it.

The monarchy’s continued existence in modern Uganda is an anomaly that requires constant justification. Its power is cultural, not executive; its influence is persuasive, not coercive. In a landscape dominated by the raw, militarised power of the Museveni dictatorship, the monarchy’s utility and safety derive from being perceived as a complementary, rather than competitive, force. By positioning itself as the guardian of civility and legal process—especially during moments of acute state-sponsored uncivility—it performs a vital service for its own preservation. It casts itself as the sober elder, the repository of tradition and calm, intervening not to overthrow the table of power, but to chastise those rocking it too violently.

This strategy is deeply pragmatic. It aligns with the regime’s own need for periodic, manageable criticism that does not challenge its foundational authority. A monarchy decrying electoral violence focuses attention on the symptoms (the beatings, the blockades) rather than the cause (a dictatorship maintaining power by any means). This allows the regime to absorb the criticism as pertaining to operational excesses, not structural illegitimacy. For the monarchy, this calibrated critique achieves crucial aims: it demonstrates continued engagement with national affairs, validates its role to its own constituency, and garners favourable coverage as a voice of conscience, all without crossing the red line that would threaten its state-sanctioned restoration and the vast land holdings underpinning its wealth.

This strategy is deeply pragmatic. It aligns with the regime’s own need for periodic, manageable criticism that does not challenge its foundational authority. A monarchy decrying electoral violence focuses attention on the symptoms (the beatings, the blockades) rather than the cause (a dictatorship maintaining power by any means). This allows the regime to absorb the criticism as pertaining to operational excesses, not structural illegitimacy. For the monarchy, this calibrated critique achieves crucial aims: it demonstrates continued engagement with national affairs, validates its role to its own constituency, and garners favourable coverage as a voice of conscience, all without crossing the red line that would threaten its state-sanctioned restoration and the vast land holdings underpinning its wealth.The call for a “level playing field” is thus a politically safe one. It does not question who owns the stadium or makes the ultimate rules. It is a plea for fairer play within a game whose outcome is already heavily engineered. This is the essence of its survival logic: by advocating for procedural fairness, it presents itself as a necessary check on the state’s worst excesses, thereby arguing for its own continued existence as a national asset. Its moral authority becomes its key bargaining chip in the silent, ongoing negotiation with the central state.

However, this strategy has a corrosive effect on genuine political transformation. It redirects the search for justice from the grassroots upwards, towards a figurehead. It implies that stability and morality flow from traditional, hierarchical authority rather than from the self-organised power of communities, trade unions, and civic associations. It subtly reinforces the idea that the people need guardians—whether in military fatigues or royal robes—to manage their affairs and mediate their conflicts.

Ultimately, the monarchy’s survival depends on this careful curation of its image as a stabiliser. True, lasting stability, however, will not be delivered from a palace. It will be built from the ground up, in the daily practices of communities learning to resolve conflicts, manage resources, and uphold one another’s dignity without appeal to unearned authority. The most profound threat to the monarchy’s strategy is not the dictator’s ire, but the quiet, collective realisation of a populace that discovers it can, in fact, keep its own head, and build its own peace, without requiring the guiding hand of a crown.

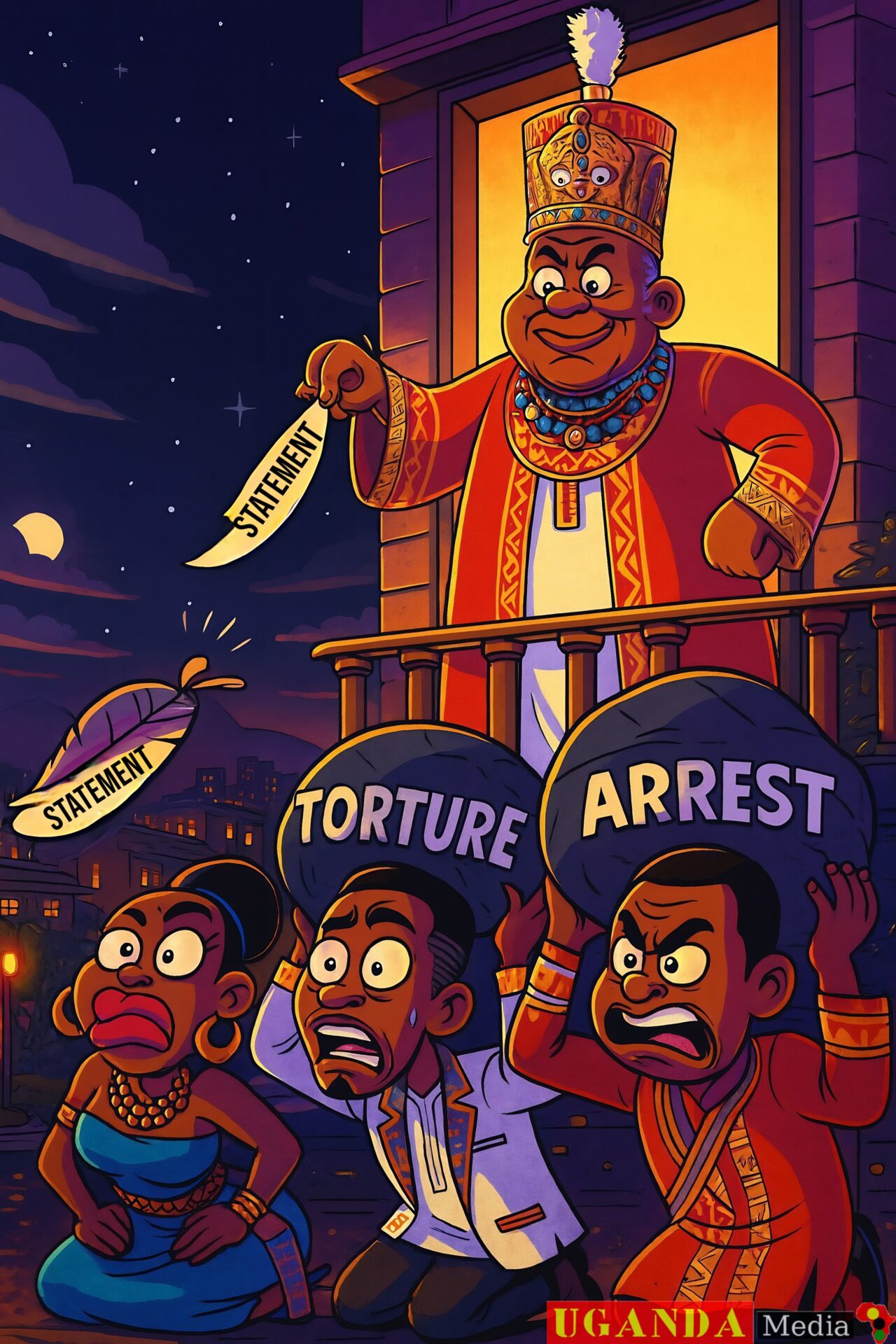

The Theatre of Morality: A Cost-Free Performance on a Blood-Stained Stage

In the grim political economy of resistance, where the currency is often courage and the price is frequently freedom or life, the recent royal intervention represents a transaction of an entirely different order. It is the embodiment of “cheap politics”: a high-visibility, low-risk manoeuvre that extracts maximum reputational value at minimum cost to its author. While activists, community organisers, and ordinary citizens bear the brutal weight of state repression—facing torture, disappearance, and imprisonment—the statement from the palace offers a sanitised, symbolic counterpart. It is a performance on a safe, well-lit stage, carefully separated from the dark realities of the struggle it purports to address.

The calculus is stark and revealing. For the Kabaka, the cost of issuing a statement calling for peace and impartiality is negligible. It requires no personal confrontation with the state’s security apparatus, no legal jeopardy, and no threat to the vast estates and assets underpinning the monarchy. It is a moral assertion devoid of the accompanying material risk that defines genuine dissent. Yet, the returns are substantial. Domestically, it reinforces his image as a unifying father figure, a voice of conscience above the fray. Internationally, it plays perfectly to diplomatic and NGO audiences who seek ‘moderate’ local voices to engage with, burnishing the monarchy’s credentials as a civilised, stabilising institution in a turbulent region.

This performance stands in devastating contrast to the political economy of actual resistance. The real work—documenting atrocities, organising clandestine meetings, mobilising communities under the threat of infiltration, standing firm before armed police—is carried out by individuals with no hereditary protection, no palaces to retreat to, and no guarantee of safety. Their capital is their bodily integrity and their liberty, both of which are on the line daily. When they are beaten in safe houses or charged with fabricated offences, no cultural reverence shields them. Their politics is, by brutal necessity, expensive.

This cheap political calculus is, paradoxically, valuable to the very dictatorship it seems to critique. It suits the Museveni regime to have a ‘respectable’ opposition to its violent methods that comes from a source which does not fundamentally challenge the architecture of power. The palace’s condemnation provides a pressure valve for international concern and domestic disillusionment, funnelling them into a dead-end of moral appeal rather than into more dangerous avenues of mass mobilisation or direct action. It helps maintain a facade of political debate and moral scrutiny, a theatre which the dictator is content to allow, as it distracts from the harsher theatre of his security forces.

This cheap political calculus is, paradoxically, valuable to the very dictatorship it seems to critique. It suits the Museveni regime to have a ‘respectable’ opposition to its violent methods that comes from a source which does not fundamentally challenge the architecture of power. The palace’s condemnation provides a pressure valve for international concern and domestic disillusionment, funnelling them into a dead-end of moral appeal rather than into more dangerous avenues of mass mobilisation or direct action. It helps maintain a facade of political debate and moral scrutiny, a theatre which the dictator is content to allow, as it distracts from the harsher theatre of his security forces.Therefore, this intervention is not solidarity; it is a form of political shadow-booking, where credit is claimed for highlighting a debt paid by others. True commitment to justice is measured not by words released to the press, but by tangible action and shared risk. The future of Uganda will not be shaped by those who make cost-free appeals from balconies, but by those who, rooted in their communities, build networks of mutual defence and direct democracy from the ground up—a form of politics that is inherently expensive, because it invests everything in the belief that people can govern themselves, without crowns or dictators. The most profound political acts are not statements, but the slow, dangerous work of making the state, and its ornamental alternatives, irrelevant.

The Mask and the Face: Disentangling Heritage from Authority

In the rich tapestry of Ugandan society, cultural heritage provides a vital sense of continuity, identity, and community. The languages, rituals, stories, and artistic traditions of the Buganda kingdom, like those of all Uganda’s nations, are a profound inheritance to be cherished and sustained. However, a critical and often deliberately blurred distinction must be made: between honouring a cultural heritage and endorsing the political power of a hereditary institution within a sovereign republic. To confuse the two is to fall into a trap that stifles democratic progress, for it is entirely possible—and indeed necessary—to hold the former in high esteem while resolutely opposing the latter’s intrusion into the political sphere. This is the essential work of separating the cherished face of tradition from the political mask of hierarchy placed upon it.

Cultural heritage lives in the daily practices of the people. It is in the Luganda spoken in homes and markets, the bark cloth patterns crafted by artisans, the folk tales told to children, and the communal celebrations that bind generations. This heritage is democratic by nature; it is owned, shaped, and propagated by the community itself. It requires no royal decree to validate its worth. In fact, its most authentic expressions often flourish at the grassroots, away from the formalised ceremonies of the court. Defending this living culture from homogenisation or erosion is a worthy cause shared by many.

The political power of the monarchy, however, is an entirely different construct. It is a system of governance, a structure of inherited, unaccountable authority that claims a right to influence, mediate, and comment on the governance of a republic founded on the rejection of such principles. When the Kabaka issues a statement on national electoral conduct, he is not acting as a curator of culture, but as a political actor. This intervention leverages the deep, genuine affection for Buganda’s heritage to lend weight to a political opinion, thereby conflating love for tradition with acquiescence to traditional authority. It is a strategic conflation, suggesting that to criticise the political role of the monarchy is to disrespect the culture itself—a false equivalence that protects privilege by silencing critique.

The political power of the monarchy, however, is an entirely different construct. It is a system of governance, a structure of inherited, unaccountable authority that claims a right to influence, mediate, and comment on the governance of a republic founded on the rejection of such principles. When the Kabaka issues a statement on national electoral conduct, he is not acting as a curator of culture, but as a political actor. This intervention leverages the deep, genuine affection for Buganda’s heritage to lend weight to a political opinion, thereby conflating love for tradition with acquiescence to traditional authority. It is a strategic conflation, suggesting that to criticise the political role of the monarchy is to disrespect the culture itself—a false equivalence that protects privilege by silencing critique.The Museveni dictatorship itself actively fosters this confusion. By engaging with the monarchy as a semi-official political entity—through ceremonies, recognitions, and negotiated settlements—the regime legitimises the idea that traditional leaders are rightful stakeholders in national governance. This serves the dictatorship’s purposes by promoting a fragmented, tiered model of citizenship where people are viewed first as cultural subjects and second as civic equals, making a unified, secular republican challenge to his rule more difficult to organise.

Therefore, the path of genuine progress requires intellectual and civic clarity. One can, and should, advocate for the protection of Luganda, support the preservation of historical sites, and participate in cultural events, all while maintaining a firm, principled stance that the government of Uganda must be a matter for its citizens alone, without interference from hereditary offices. The true strength of a culture is not measured by the political pronouncements of its ceremonial heads, but by the vitality and autonomy of its practice among the people.

Ultimately, preserving culture and deepening democracy are not conflicting aims; they are strengthened by separation. A living culture is one that evolves freely among its people. A healthy republic is one where all authority is derived from and accountable to those same people, without the shadow of ancestral privilege. We must learn to honour the face of our heritage while removing the political mask, recognising that the most profound respect for tradition lies in ensuring it is never used as a tool to undermine the sovereignty of the citizen.

The Cynicism Spiral: How Elite Dialogues Erode the Foundations of Citizenship

When a hereditary monarch intervenes in the political crises of a republic, and when that intervention is aimed at a dictatorship that has hollowed out democratic institutions, the message conveyed to the ordinary citizen transcends the specific words spoken. The broader, more corrosive implication is the deep and systemic erosion of trust. It fosters a profound societal cynicism, teaching the populace that all centres of power—whether seized by the gun, inherited by blood, or ostensibly conferred by a compromised ballot—are ultimately engaged in a closed, self-serving dialogue. The citizen is reduced to a spectator of this elite discourse, a dynamic perfectly captured by the adage that “when elephants fight, it is the grass that suffers.” In this case, even when elephants appear to debate, the grass is reminded of its powerlessness.

This mistrust is not a passive feeling but an active, disabling force. It arises from the observable gap between the performance of authority and its practice. The state’s institutions, most notably the Electoral Commission and the security agencies, routinely demonstrate partisan allegiance rather than public service. Into this void steps a traditional authority, leveraging historical and cultural capital to present itself as a moral arbiter. Yet, this very act confirms a grim suspicion: that resolution and justice are not products of transparent systems or citizen action, but commodities to be brokered in back-channel negotiations between different flavours of elite. Whether it is a general, a monarch, or a lifelong dictator speaking, the underlying grammar is one of power preserved, not power redistributed.